Meet Firdaus Sani, a fourth-generation Orang Laut, or “Person of the Sea” in Bahasa Melayu. More than a decade before he was born, Mr Firdaus’ family was asked to evacuate from Pulau Semakau.

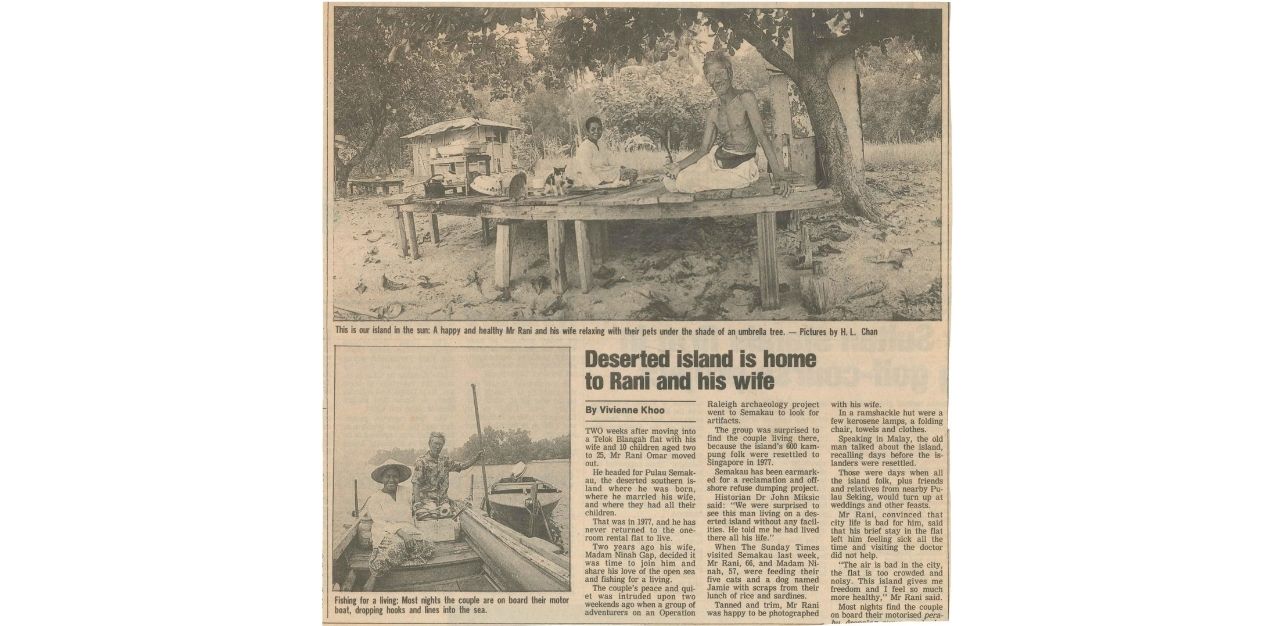

There was very little compensation and virtually zero consultation. Despite the efforts of Mr Firdaus’s grandfather, Rani Omar, who rallied the voices of the indigenous peoples, the government remained uncompromising in their relocation mandates.

Today, Mr Firdaus is faced with the looming possibility that his people’s traditions and culture will soon disappear amid the cacophony of cosmopolitan Singapore. “My young nieces and nephews know very little of our island traditions, and this rapid dilution of our heritage actually scares me quite a bit.”

TheHomeGround Asia caught up with Mr Firdaus at West Coast Park, a place that holds much significance to the Orang Pulau — or Island People — of Singapore. What was once a coast entirely occupied by Singapore’s indigenous people has now become walled off to prevent erosion. Their sampans are forced to occupy what little real estate that has been left for them, almost entirely eclipsed by container ships and luxury yachts.

Mr Firdaus, who used to work for an environmental NGO, says, “I always felt that little bit of excitement when Pulau Semakau is mentioned… but then it just goes straight to ‘Pulau Semakau is a landfill’.”

“I think it’s great that the tours currently at Pulau Semakau focus on protecting the biodiversity there, but I wish there is a heritage component that incorporates what life used to be like on the island,” he says. It is with these considerations in mind that he founded the Orang Laut SG project, curating all the stories that continue to inform him of the way of life he would otherwise have known first hand.

Join TheHomeGround Asia in finding out more about Singapore’s indigenous islanders, their struggles in adapting to city life, and how Mr Firdaus has helped reclaimed their narrative amid pushbacks and scepticisms.

TheHomeGround Asia (THG): What does being an Orang Laut mean to you?

Firdaus Sani (FS): People often look at Orang Laut simply as fishermen but there’s so much more behind that. In history books, Orang Laut are known as seafarers, sometimes even warriors who defended the straits back in the 19th century. I think it’s really important for us to recall our glory days.

Sometimes I question if the Orang Laut of today – such as myself – can still be called that, since we are no longer living at sea. But I do believe that it is an identity, a way of life that still resides in us. I asked my aunts and uncles, who’ve actually lived on Pulau Semakau, if they still associate themselves as an Orang Pulau (islander) or an Orang Laut. They said yes, definitely, because the Jiwa Laut (spirit of the sea) will always be with them.

It’s very evident. When we go out to sea now, they would still be able to know how to navigate the seas. Judging just by the wind and where the sea currents are moving, they’d say, “go that way, the school of fish is located in that area,” and they’d be right. These are the kinds of things that they learned just by being on the island for so many years, and you cannot take this knowledge or identity away from them.

THG: What is one exciting tale that your elders have told you about life on Semakau?

FS: My late grandfather told me once that when he and my grandmother were out at sea alone, they were attacked by pirates. These pirates weren’t from Singapore, and they had parangs (a machete used across the Malay archipelago). They told them to hand over all their belongings — including the (boat) engines, because engines cost a lot of money back then. They were basically robbed in broad daylight.

So, my grandparents – they were fierce people – thought they would die whether they fight or not, so they decided to defend themselves and their belongings. They held up their kiaus (oars) to the pirates’ parangs, ready to fight, and the pirates ran away.

Yeah, that’s what they were like – really garang (fierce) la. These are the kind of stories that actually really intrigued me… about who we are, and the kind of life I wish I had known personally.

THG: What was the social structure like on Pulau Semakau?

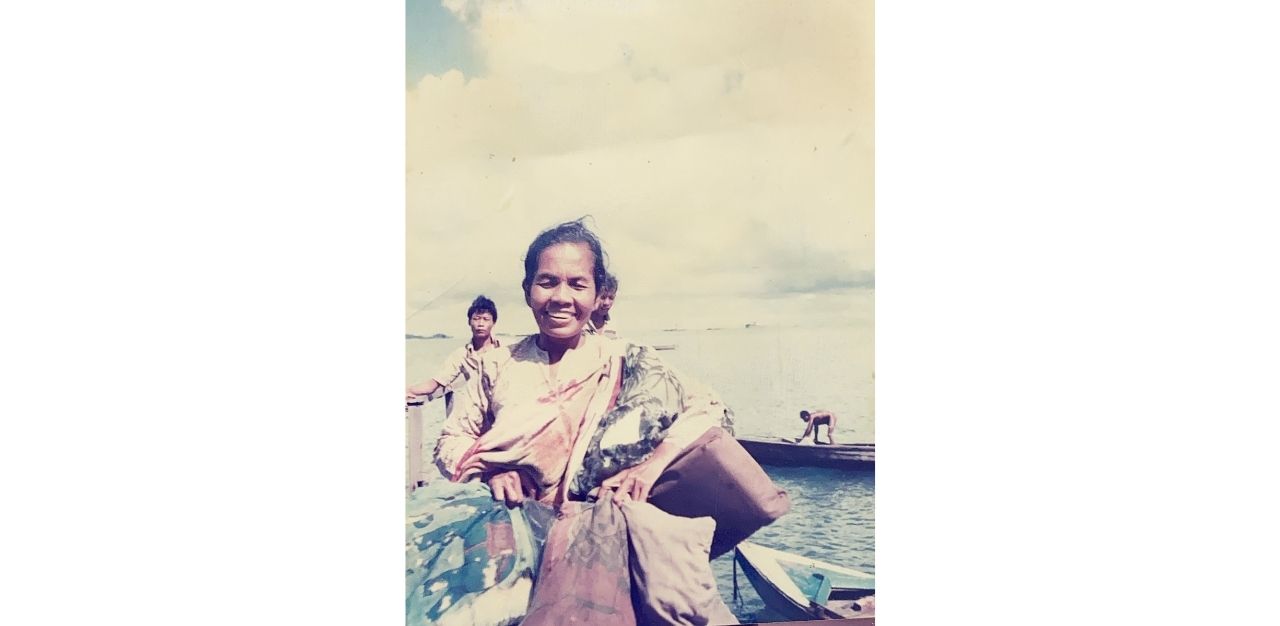

FS: My late grandfather Rani Omar, was a prominent figure in the islander community because he was an expert fisherman. Orang Laut are usually portrayed as male-dominated and you see these male fishermen going out to sea. Of course, this depiction is true, but the female figures are often were overlooked. The women then had to take care of their younger siblings, cook for the family, and still go out to sea to fish with the men. One of them was my grandmother – strong-willed, fierce, and she’s super garang, I tell you. She’s the kind of person who shaped how my aunt and mum turned out today. They were trained to become matriarchs of the family.

There was once I was out at sea with my grandparents, and the engine stopped working. My grandfather tried to restart it but it didn’t work. So my grandmother took out her kiau, and she rowed us all the way back to shore. It was from the middle of the sea to Pasir Panjang. I was an eight-year-old boy who held her in awe, starry-eyed the whole way back. She was the kind of strong-willed woman figure I had growing up.

THG: What was it like when your elders had to relocate, and what do you wish the government could have done differently?

FS: We were compensated [purely] based on the size of the house, and also the trees that surrounded the house. For example, if there was a fruit-bearing coconut tree, the family was given about $25 to $30 extra. So my family was given about $3,000 to relocate to Singapore. It wasn’t a lot of money – in fact, too little.

My grandfather told me that he worked with a few other islanders who didn’t want to move. He tried to voice their opinions but was still asked to leave. I wish there could have been a consultation process then. The government does it now but back then I don’t think they did. I wish we could have also retained Pulau Semakau as it was but with more amenities, and perhaps looked to other solutions to address our landfill issues as well.

THG: Did your family have a hard time adjusting to city life?

FS: When my mum and my aunt first moved to [mainland] Singapore, they were like deers in the headlights. They didn’t know how to use a washing machine because they used to wash all their clothes by hand. It was a very different way of living. They didn’t know where to find food before they learnt about supermarkets and NTUC Fairprice. They also needed to have money. So most of my relatives took on odd jobs as painters, shipyard operators, just to earn that extra bit of money to survive in the city.

THG: What lessons did you learn from your islander heritage?

CH: My late grandfather always taught me to bersyukur, which means “be thankful for what you have”. Living in [mainland] Singapore, we are not able to experience the difficulties the islanders used to face. At the supermarket, you can get any type of fish you want, and when they don’t have it, you’d grumble a little bit. I used to do this also, but when I got home, my mum would say, “it’s okay. Do you know how difficult it is to catch a sotong?”

The islanders had a deep respect for nature. Even before going out to sea, there would be a greeting we’d need to give to the sea itself because we believe it is a living, breathing thing. We need to respect it, and if it gives us food, we have to be grateful. These were the kinds of island traditions that were imparted to me by my grandfather. He always reminded me that when we go out to sea, we just catch what we need and then leave.

This, with the environmentalist side of me, makes me always look at where the fish we eat comes from. Are we contributing to overfishing and overconsumption? We need to be able to look at local sources of food and always try to only consume what we need.

THG: Why did you start the Orang Laut SG project?

CH: Before I started this project, the Orang Laut narrative was very much told by academics only. Of course, there have been historians who have looked into our methods of fishing and way of life, but that was only scratching the surface. We were sometimes referred to as “sea gypsies”, or even “lazy’, and life on an island would sometimes be depicted as “super chill”. That’s not true at all. That portrayal really saddens me because we are hard-working individuals who had to work hard to survive – literally. My grandmother and mum used to remind me that if I were still living on Pulau Semakau, I would not have survived because life was actually super difficult.

My young nieces and nephews know very little of our island traditions, and they don’t speak Malay as well as we do. The dilution of our heritage actually scares me quite a bit. So that’s why I took that leap of faith, and thought to myself, if I don’t do this, no one will. The time is now for me to reclaim our narrative, let people know what the Orang Laut culture is all about, and make sure that our island traditions are recorded and kept alive.

THG: Did you face any pushback when reclaiming your narrative?

FS: Sometimes, even within my own Malay community, and also among the [mainland] Singaporeans, we have been labelled as “backward islanders”. This is the stigma that my aunts and uncles still face today – that they are “Orang Pulau”, have different traditions, and are seen as lesser in a way. Some even question whether we can really call our family Orang Laut, or they get very hung up on the semantics of Orang Pulau versus Orang Laut.

The perspective that I would like to offer is very much based on what I was told. These are the stories of the living descendants of those who used to live on the different islands of Singapore, and I think our stories count. I think we need to be able to recognise the importance of oral history, and not discount it as hearsay just because it’s not in our history books. We need to be able to take these accounts as truths, use their voices as very important parts of history because we do not have much left to preserve.

THG: How has the Orang Laut SG project impacted your family?

CH: I started this project because I felt people like my mum and my aunt need to be able to reclaim their identities, and know that their knowledge and experiences carry weight and value. And I think it has indeed given them a little bit – if not, a lot – of confidence to really talk about who they are and claim back their traditions and heritage.

Immerse yourself in Orang Laut culture via Firdaus Sani’s Orang Laut SG project here.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.