Abused and starved to death by her employer, Ms Piang Ngaih Don was just one of many domestic workers who have suffered under the hands of errant bosses in Singapore. TheHomeGround Asia explores how we might ensure egregious incidents like this never happen again.

Hailing from a remote village in Myanmar’s Chin State, Piang Ngaih Don moved to Singapore in 2015 to earn a living, leaving her young son behind in the care of her siblings. Tragically, Ms Piang died just a year later as a result of the abuse inflicted upon her by Singaporean Gaiyathiri Murugayan and complicit members of the household.

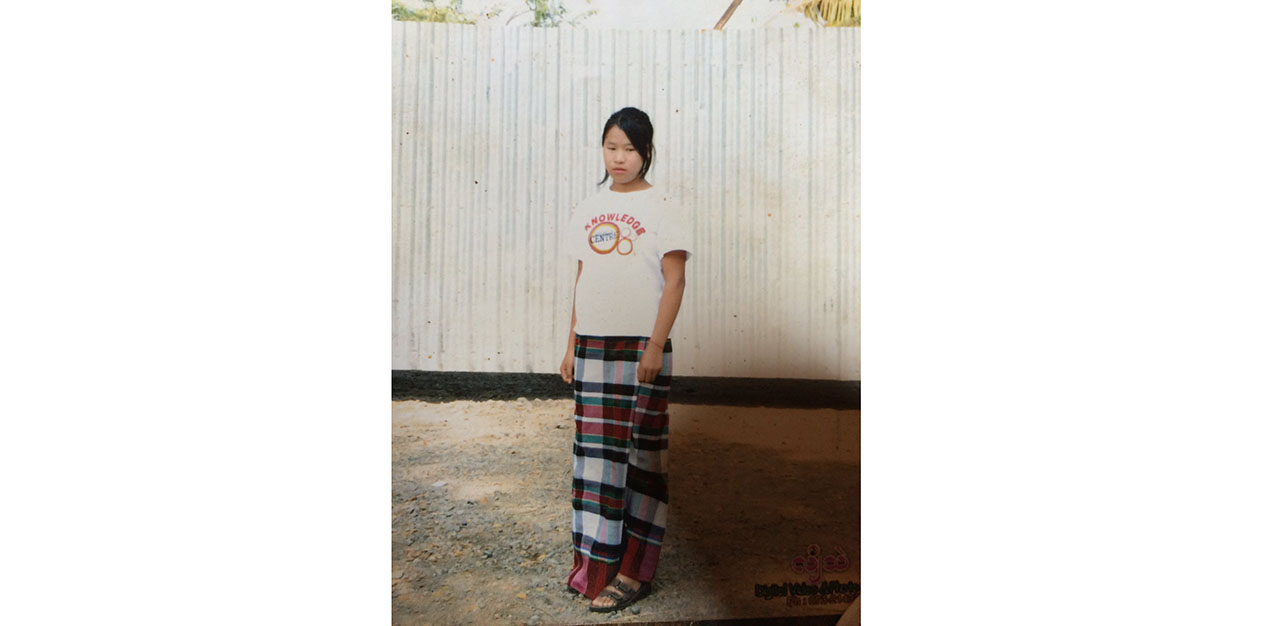

In 2016, the late Piang Ngaih Don from Myanmar died at 24 years old from being consistently abused by her Singaporean employer. (Source: Lynn Lee / Facebook)Closed-circuit television footage from security cameras installed in the flat have exposed the brutality that the victim suffered on a daily basis. She was starved, weighing a mere 24kg at the time of her death. She was assaulted with household objects; tied to a window grille and left to sleep on the floor; grabbed by the hair and thrown around like a rag doll; and burned with a hot iron. She was given no respite, allowed only five hours of sleep each night and forced to shower and relieve herself with the door open.

An autopsy uncovered 31 recent scars and 47 external injuries on the victim’s body, and revealed that Ms Piang had died of hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy, a type of brain injury caused by oxygen deprivation and lack of blood flow, with severe blunt trauma to the neck.

Senior Counsel Mohamed Faizal, who led the prosecution, said, “That one human being would treat another in this evil and utterly inhumane manner is cause for the righteous anger of the court; and the law must come down with full force to appropriately vindicate the fundamental values of society and human dignity that have been violated in this case.”

A flood of support

Following a court hearing on February 23, in which Gaiyathiri pleaded guilty to 28 charges including culpable homicide and wrongful restraint, the non-profit Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics (HOME) took to social media to announce that it would facilitate the remittance of all funds gifted by the public to Ms Piang’s family through close collaboration with the Myanmar Club and the Myanmar Embassy.

Meanwhile, Singaporean filmmaker Lynn Lee also put up a post on social media recounting her trip to Dimpi Village a few years ago to meet Ms Piang’s son and siblings while producing a documentary on underage domestic workers. She also shared a link directing others to HOME’s Facebook page in response to the overwhelming number of people who “reached out to ask how they [could] help”.

On 3 March, HOME posted an update saying it had collected S$206,565.40 from 2,551 donors, but had to halt donations with immediate effect due to requirements by “internal compliance and governance”.

“I would be willing to donate because someone from my community has done a grave injustice,” says Singaporean Emily Yap. “And justice, in the form of payment for loss [incurred], is not being meted out to her family by law. She came to earn money to support her son and family financially, so it is only right that we [in turn] help her family.”

A problematic dichotomy

Sadly, Ms Piang is not the first and unlikely the last foreign domestic worker (FDW) to find herself on the receiving end of maltreatment by employers in Singapore. Numerous incidents of abuse have hit the headlines since the Foreign Domestic Maid Scheme was introduced in 1978, and the cases keep piling up.

In 2019, for example, Singaporean couple Tay Wee Kiat and Chia Yun Ling were sentenced to jail for the physical and emotional pain they wreaked on domestic workers Moe Moe Than and Fitriyah. While last year, Nuur Audadi Yusoff admitted to repeatedly abusing Indonesian domestic worker Sulis Setyowati, driving the Indonesian helper to such desperation that she climbed down 15 storeys from the balcony to escape.

Add the shocking saga of Piang Ngaih Don to this growing list, and could FDW abuse be considered a rampant problem in Singapore?

It also begs the question: how can we reconcile the seemingly contradictory faces of Singaporean society – on the one hand, exploitative and abusive, and on the other, generous and supportive?

It is a query that has confounded some of the greatest minds in the history of humanity. For thousands of years, philosophers have debated whether humans are innately good or evil, without reaching a clear consensus. But to avoid wading into the fray of a Hobbesian versus a Rousseauian understanding of human nature, suffice it to say that we contain multitudes – we possess an enormous capacity for good and an unsettling amplitude for evil.

If we were to be completely honest, a lot of us would probably admit to feeling frustration and anger at times, maybe even the urge to hurt. But it is one thing to experience an impulse, and a whole other to act on it. So what is stopping us from giving in to our basest instincts?

Speaking to the media on 25 February, Singapore Law Minister K. Shanmugam says that people don’t walk around with clear indicators that show they are evil.

“The point I will make is that people who seem ordinary are capable of extraordinary evil, and there are two pillars in any society to keep evil in check,” he explains. “One, is education. Two, we need rule of law… The law has to come down with full force when the rules are broken.”

Law Professor Low Kee Yang concurs: “I do think you need to educate these people who abuse their [domestic workers], because they know they’re doing wrong.

“You also need to set an example. Some people say that [Gaiyathiri] should go in for life imprisonment, and because of the seriousness of this particular offence, I would agree,” Mr Low says in an interview with TheHomeGround Asia.

“Law needs to have a kind of deterrent role. We must [impose] serious punishment so that other people would be less likely to [engage in abusive behaviour].”

The path forward

In the wake of Ms Piang’s death, the Government has sought to enhance the welfare of foreign domestic workers, undertaking a review of three key areas to ensure such egregious incidents never occur.

“There is no place for abuse against foreign domestic workers in Singapore. There is simply no place for it,” emphasises Singapore Manpower Minister Josephine Teo.

She adds, “We appreciate the many foreign domestic workers who have come to Singapore to help us look after our families. We recognise the sacrifices that they have made, and we are determined to put an end to any form of abuse towards them and to ensure their safety.”

The review aims to shore up safeguards against abusive employers, improve how doctors report symptoms of abuse or distress in FDWs and involve the community in flagging possible cases of abuse.

In addition, Minister of State for Manpower Gan Siow Huang highlighted in Parliament (on 8 March) that the Government is exploring other protective measures, such as enforcing a mandatory day-off for FDWs (at the moment, FDWs are given a weekly rest day, but they can agree to work on their day-off in exchange for remuneration); institutionalising regular check-ins with FDWs by their employment agencies; working with the Centre for Domestic Employees to conduct interviews with newly-arrived FDWs in their native languages; and bolstering the ways in which doctors detect and report abuse during the compulsory biannual medical examinations.

The lacunae in the system

But are these steps enough to solve the pervasive problem of domestic worker abuse? Take, for instance, the issue of physician accountability. Two months prior to her death, Ms Piang had visited a doctor at the Bishan Grace Clinic for a cough, runny nose and swelling on her legs. The doctor had noticed contusions around the victim’s eye sockets and cheeks, but Gaiyathiri claimed that the bruising was caused by the victim’s clumsiness. The doctor did not to follow up on the matter and/or alert the authorities.

Given this unfortunate decision, it appears necessary that the Government makes it mandatory for doctors to report all injuries or indications of abuse in FDWs to the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) – and make the failure to do so punishable by a fine or a suspension. Moreover, the standard procedure in medical examinations ought to be updated to afford FDWs more opportunity to speak out about any mistreatment they might be experiencing.

A local doctor, who wishes to remain anonymous, suggests to TheHomeGround Asia that while striking an errant doctor off the medical register would be too drastic, MOM should lay down stricter rules with regard to the medical screening. This includes allowing a domestic worker to see a doctor with a nurse in attendance instead of her employer so that the doctor can talk with her in private about her working conditions and well-being; incorporating a weigh-in and a physical examination in the consultation so as to enable identification of abuse; and recording any signs of abuse on the screening form in red ink so that the information stands out clearly to MOM.

“It’s about time Singapore does more to prevent FDW abuse, which I believe is far more prevalent than reported,” Ms Yap adds. “MOM should do a lot more, knowing there are many hotbeds of [FDW] abuse. They should have an investigation arm – people who go to households and check on reports of abuse. We do this for citizens in the social service sector, and should do the same for FDWs.”

The importance of attitude

More crucially, however, Singaporeans must overhaul our mindset towards foreign domestic workers. For far too long, many of us have viewed and treated FDWs as servants, robots, commodities, even punching bags. Maybe it boils down to the fact that we place too much emphasis and value on money, power and status (our ideology of meritocracy has often been criticised for breeding a culture of elitism), and as a consequence, look down on anyone deemed less than ourselves.

Hence, what needs to change to stem the tide of abuse is our own attitude. We must recognise FDWs as fellow human beings, or better yet, as trusted and treasured members of our families. We must cultivate a sense of empathy, not just when tragedy strikes, as in Piang Ngaih Don’s case, but at all times. We must speak up whenever we notice abuse. And we must strive constantly to break new ground, not just take action when things go wrong and it is often too late.

In short, we must do better.

Join the conversations on THG’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.