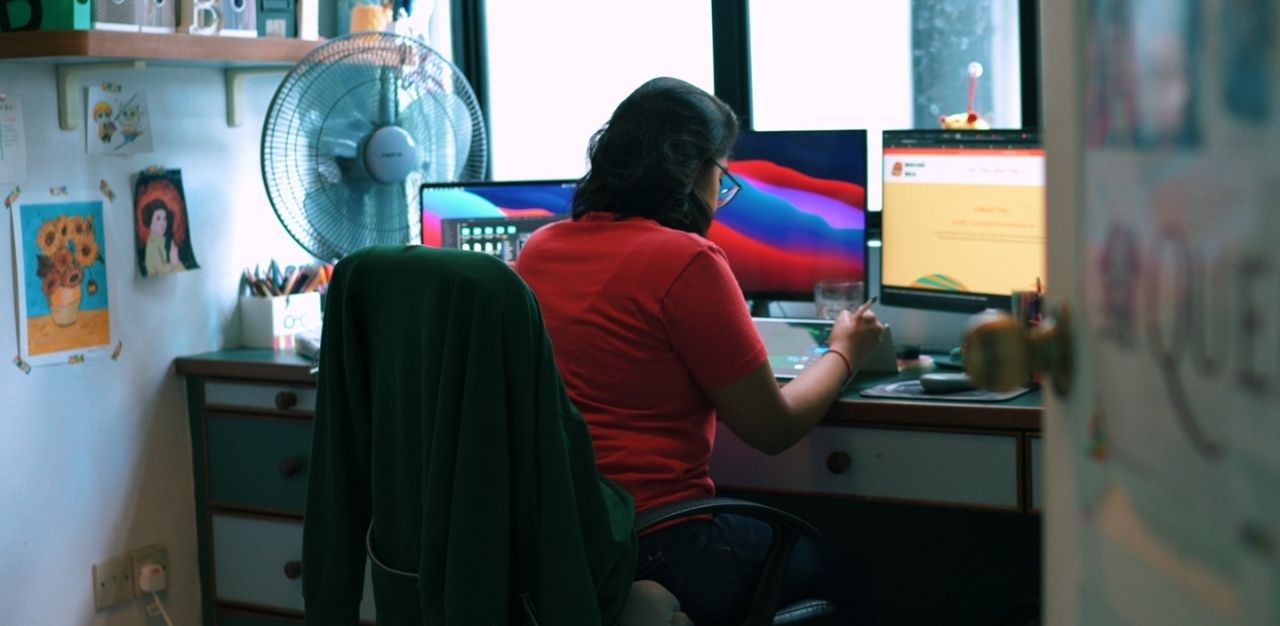

Bhavani Bala has been drawing for as long as she can remember. Doodles in the back of her textbooks, art classes as a child, and a healthy diet of Disney movies ignited her desire to be an animator. Alas, her Asian upbringing would not allow it.

“Because we are Asian and we have to do the respectable thing… My family was like, ‘Oh, you can draw, why don’t you try architecture?’” she recalls.

Being a good Asian child, she did; leaving her home country of Kuwait and enrolling in the National University of Singapore’s Architecture course. But she soon learned that architecture involved a whole lot more than simply drawing, and was not something she was keen to pursue as a career.

Instead, she chose to chase her passions, and is now making the transition into illustration, all while holding down a full-time job as a creative designer at a creative AI firm, being an improv coach on the side, and going through the arduous process of applying for a Master’s degree in animation.

It may seem like she has it all figured out, but Ms Bala admits that she feels like she is “just out of the threshold” in her journey.

She explains: “In storytelling, we talk about the hero’s journey. I feel like I’ve just hit my first story beat. Obstacles have come, I’ve overcome them, but I’ve not hit the meat of the story.”

While she trudges along on her journey as an artist, Ms Bala is likewise on a neverending journey to discover her identity and find a place for herself in this complex world. As a brown, neuro-divergent, and gender non-conforming individual, Ms Bala finds that her identity is often contrary to societal expectations.

“You’re expected to do certain things and be a certain kind of person. These identities obviously make me unique, but I also had to fight against a lot of [them],” she rues.

Today, she is still working on unravelling preconceived notions about her gender and ethnicity, and learning to live with anxiety and depression, which she was diagnosed with in 2015.

Speaking with TheHomeGround Asia, she shares more about her mental health journey, her discovery about her identity, as well as the inspiration behind her art, and how it continues to reflect her life experiences.

(NOTE: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Bhavani Bala: [My art is] whimsical. That’s the first word that comes to my head when I look at my work. I was heavily inspired by Vincent van Gogh growing up. His story really resonated with me. He only really became famous after he died, which is such a tragic tale that I love it so much. He was very pioneering in his time but no one really recognised it, and I really feel for him, and his struggles with mental illness, and the way it works with his art, in a way that it did not come across in his art. It’s always very happy, it’s very whimsical, it’s very fantastical. And that was very inspirational.

Right now with my art, a lot of it is focused on my struggle with mental illness. That’s my outlet, so a lot of my work reflects that – just a feeling of being submerged, or the feeling of having to scratch yourself away, and the real you is underneath.

THG: Is there a message in the art you create? What do you hope people will take away from it?

BB: The point of my work is just to tell other people who have mental illness that they are not alone, because when I was struggling, I felt very, very much alone. And I don’t want other people to feel that way. I want to start conversations, I want to have people look at my work and be like, ‘Oh, I resonate with that.’

I had someone recently tell me that they saw my print, called the Tear Away/Hide Away piece, where there are two people scratching their faces, but slightly differently. They said that they really resonated with that piece, because it reflected how they were feeling in their life. I was very happy about that, because that was why I created it in the first place.

Other than that, I think a lot of my work reflects fantastical worlds, because I’m very obsessed with storytelling. The thing with storytelling and characters is they’re very real. As much as fairy tales are very romanticised or very exaggerated, at the end of the day, they are people with real feelings. As a child, when you read books, a lot of [the draw is the escapism it provides]. That feeling of wanting to escape from the current situation leads to wanting to create a fantasy world. I think it’s a very natural reaction to not feeling great in the real world.

THG: When does a thought become an art piece?

BB: My process in art and improv is very similar in the sense that I make a lot of associations in my mind. So if I see a thing, my brain goes, ‘Oh, that’s a weird thing. What if?’

When I talk about stuff like my mental health, I just let myself feel my feelings and I try to visualise it as much as possible. So if I’m having a particularly bad day, I try to describe it and make it as visual as possible. Because when I have that visual image, I can easily translate that as well. I remember telling my therapist recently that I felt like I was in transit in an airport for a very long time, and my plane was constantly getting cancelled. I think I was feeling like I was languishing, and this was my way of visualising it.

That’s the process. It goes through sketches. It goes into my iPad, and then it becomes a digital drawing.

THG: You mention that a lot of your art is inspired by your mental health journey, and you have also alluded to not feeling great in the real world. Can you share a little more about that?

BB: I never really realised that something was ‘wrong’ until university. It was a very difficult journey, because of a) the stigma that related to mental health, and b) the lack of resources. I felt very alone, like nobody really understood me. I would go to counsellors and they would dismiss it as burnout. When I finally got myself to a real psychiatrist, she diagnosed me with depression and anxiety within the first 10 minutes of talking.

I am taking medication for my mental illness. It’s a long process. Healing is not a linear graph, it’s a sine wave, that’s what I keep telling people. Some days you just feel like absolute crap but it’s part of the journey.

THG: Can you elaborate more on how your mental health affects or influences your process of creating art?

BB: I’m not a fan of the phrase, ‘You need to suffer to do art.’ If you want to take the example of Vincent van Gogh, he was very depressed. Now they’re thinking that he might have had bipolar disorder. But some of his best work came when he was in recovery, not when he was depressed. Sure, the processing of the pain will lead to work. But you need to recover from that. The days where I really cannot create are the days when I’m not feeling good at all. So as much as these feelings contribute to my work, it only happens when I’m recovering. Suffering is not art.

THG: Besides being an illustrator, you are also an improv coach. How did you first get introduced to improvised theatre?

BB: Around the time I started feeling mentally ill, I got a message from my friend saying that they [The Improv Company] were holding an improv workshop in NUS, and she thought I would like to go. I decided there was no harm trying.

[At the initial session], I enjoyed it so much that I just kept going back. It became that place where I could be myself, vent my feelings out, and nobody would judge me for it.

The first rule of improv is ‘Yes, and?’ And it essentially means you say yes to the idea that you get, then you add something more to it. I had never felt this heard in my life. I was very much listened to, my ideas were taken, and I was able to just let loose and be free. There’s a lot of play. It was a very accepting space.

That’s where it started, and it just grew from there. Now I’ve come to a place where I can teach improv, do regular shows, and go to festivals.

THG: How did improv influence the way you live your life, if it did?

BB: Over time, I realised I was a lot more open to change, to hearing other people’s opinions, to feedback, as well as just saying yes to things. I was very much a, ‘Oh, I don’t want to do this’ kind of person starting out. But now, I’m gonna try everything once. I’m less fazed by last minute changes.

At this point, I don’t think I can ever rehearse a script again. I’ve reached a stage where I don’t want to rehearse. I just go into it completely blind because I feel like I do a better job that way. So it definitely made me more confident in my real life. And I genuinely wish that I used a lot more of the principles in improv in real life, because I definitely feel like I’m the best version of myself at improv.

THG: You’ve spoken about being a brown, gender non-conforming, and neuro-divergent individual. How do all these different parts of your identity come together?

BB: It all comes together in a way that I’m able to consider myself a unique individual.

Obviously some parts of my identity definitely take over my life a lot more than others. Say, being brown, being neuro-divergent, and being gender non-conforming is a large part of my life because you have to go against societal expectations. You’re expected to do certain things and be a certain kind of person. These identities obviously make me unique, but I also had to fight against a lot of these identities.

And I think part of the journey is realising that a lot of the things that you were doing as a younger person when you’re fighting against these identities, was internalised misogyny or colonist feelings. So it’s a lot of unlearning and relearning, a lot of re-education. It’s a difficult process. You need to be willing to put in the work and be willing to change your opinions. That’s really important.

THG: What were some things that you had to unlearn, or relearn, in your journey of discovering your identity?

BB: This is funny, but liking the colour pink became a big journey. It’s very small and weird, but growing up, you know how we’re always saying, ‘Oh, I’m not like other girls. I don’t like pink.’

The colour pink and just liking the colour pink became a journey of realising that I didn’t like it, because I didn’t like feminine things. But now I’m like, it’s a nice colour, I’m gonna use it in everything. It’s oddly specific, but it felt like a big thing to reclaim the colour pink.

It’s a process of discovering whether I actually don’t like [something] or because it associates me with being feminine.

THG: What about your identity as a brown woman? You mentioned that it was something you were struggling to embrace, tell us more about that journey.

BB: A part of embracing your identity and culture is realising that not everything is actually part of your culture. A lot of the time, growing up in Indian household, you have restrictions that are put on you, under the umbrella of, ‘Oh, it’s our culture’. I see being Indian as more than that. It’s realising that some of the stuff that your parents thought were part of your culture, are actually, possibly, colonist things.

So a lot of it was reclaiming what I enjoy, which is our histories, mythologies and other cultural stuff, but also learning to distance myself from the stuff that is oppressive, which every culture has. A lot of Indian culture is rooted very deeply in the patriarchy. So understanding that, being able to question that, and being able to criticise that, I think, is very important in realising parts of your identity.

There is a quote by Robin Williams that comes to mind. He said, “You’re only given a little spark of madness. You mustn’t lose it.” That very much resonated with me. Basically, it is about embracing your unique self, and not losing that spark.

THG: How does the art you create reflect your identity, or your struggles and exploration with identity?

BB: One major thing I really want to get better at is exploring my identity as an Indian person. You know how they say, ‘Create what you want to see’. And I don’t see a lot of people that look like me in mainstream animation, or in comics, that kind of thing.

So I want to create more of that, put more of my brown identity into it, which I don’t think I’m doing a lot. And I think it’s a good way to educate myself on my own culture and my own identity.

THG: There’s been a lot of talk in Singapore about race issues recently. Where do you stand in that conversation?

BB: The conversation definitely needs to be had, and I think people need to listen a lot more. Listen to the brown people, and to the immigrants.

A lot of the time, policies are made with us not being in the room. If you actually had a conversation with someone who was affected by racism, it really opens that door to seeing us as we are. Of course, it is a difficult conversation to be had, I’m not gonna sugarcoat it. It’s very difficult, because it also involves acknowledging privileges and difficulties, neither of which we want to do, especially since Singapore does have that very beautifully sterilised exterior.

But speaking about minority issues is not going to make the quality of life for the majority worse, I think it’s going to make it better. It’s not a competition.

When we talk about racial harmony, at least in Singapore, harmony usually just means tolerance, not acceptance. Acceptance is difficult. I think we can eventually get there if we try, but we have to try.

THG: What more would you like to see in Singapore, when it comes to racial issues?

BB: Open conversation with people of authority is very important. Oftentimes, we are stuck in our own little bubble of people yelling into the void at each other. You’re preaching to the choir, essentially. But I rather expand that conversation to people who are higher up who can actually affect change, and that would be an ideal scenario.

THG: At the end of the day, what kind of impact do you hope to make with your art and the way you live your life? What do you wish people would take away, after meeting you?

BB: I want to leave a warm fuzzy feeling behind to whoever I meet. That’s enough. I want to be seen as a kind person.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.