LGBTQ activist Jean Chong has seen and experienced her fair share of homophobia – in all its repugnant and often violent forms. She says that she is desensitised to the abuse, but it must still sting, having to swallow the unsolicited vitriol of strangers who spit inanities and insanities at you on social media or in public.

“People would post [messages] saying I should be gang raped. And because I look like a butch, a man came up to me and said, ‘You should be killed, maybe beaten up.’ I was like, ‘What the hell?’ I just walked away.”

None of this has stopped Jean from spending more than 20 years – half her life, championing the rights of queer women, like herself. She began her activism in Singapore as a volunteer in her 20s for a gay Christian support network and went on to start and lead LBTQ-rights groups and projects regionally and internationally.

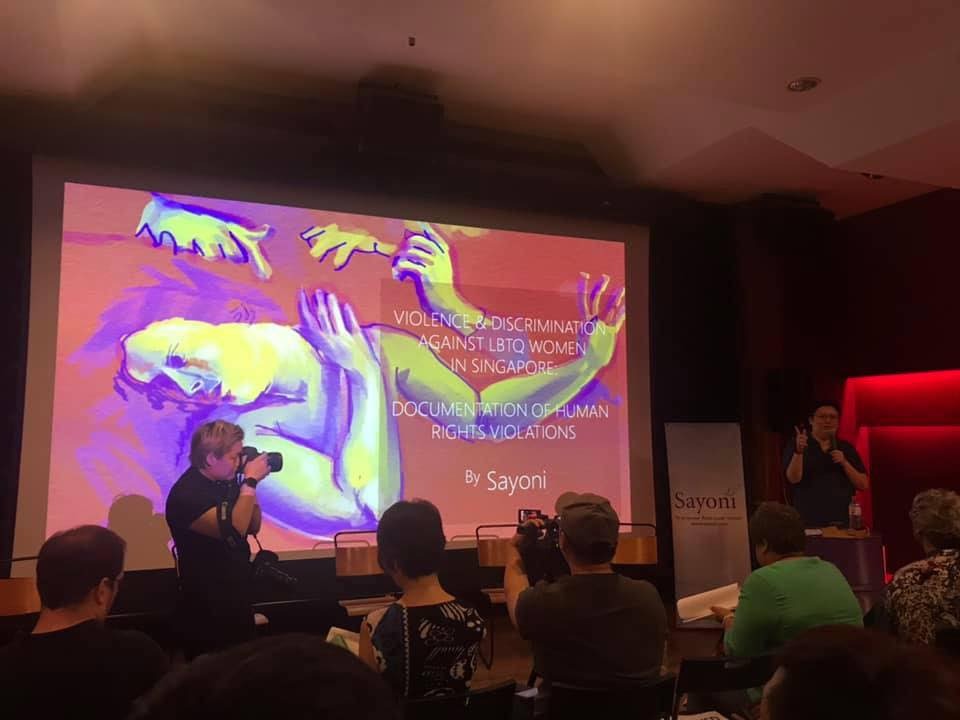

Back home, Jean co-founded Sayoni in 2007, a feminist, volunteer-run organisation that protects the rights of lesbian, bisexual and transgender women. It advocates for “equality in well-being and dignity, regardless of sexual orientation, gender identity and sex characteristics.” Sayoni led a three-woman team to CEDAW (Conference to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women) at the United Nations, in 2011.

This unflinching and ebullient dedication to the cause was ignited after discovering a book about the Stonewall riots at a bookstore. She was 19 years old, having grown up in a heteronormative bubble in 1980s’ Singapore. Queer literature and information on sexuality and gender identity were scarce to non-existent in a pre-internet world. The book was a revelation. Jean had finally found the language to normalise and give meaning to her gender expression.

NOTE: This interview was edited for clarity and length.

READ: International Women’s Day: The Strength of an Elderly Cardboard Collector

Jean Chong: It helped me understand [who I was]. I could do more research, the internet was [starting to] happen, and there’s more information. The community was also evolving. I remember, in the earlier years, someone said to me that you can be anything you want to be. I was in my 20s. The Singapore education [conditions us] to think of life as a certain pathway… a lot of people don’t think they can be anything they want to be. So that really blew my mind. It means something to me as a queer person. I can be gay. I can be anything I want to be. I don’t have to get married and have kids and have a career, I can be something different. That was my first awakening, but it’s very simple.

But when I was growing up, I struggled with a lot of anger. Society keeps telling us we are not good enough. Because you’re queer, you’re a pervert. But then one day, I decided instead of being angry, I’ll just go do something about it. Just channel the anger somewhere else.

TheHomeGround: When did you discover who you are?

JC: I knew I was different since I was five. I didn’t understand at that age this boyfriend-girlfriend thing. I always had a crush on my [female] classmate sitting next to me, but I did not understand why. I grew up in a generation where there’s no internet. I didn’t have any queer friends until I was like 19, 20 years old. If people are talking about nurture, it definitely didn’t happen to me. I just didn’t have a language. I didn’t figure it out. A lot of LGBT activists they’re all around my age, 30+, 40+, because we grew up in a generation where there were no LGBT groups. But we had clubs. It was our coming out because that was the only place to go. The only learning was from other LGB people. When the internet happened a lot of communities went online. Now we have so many different groups doing different things.

THG: Sayoni has done quite a bit of research on violence and discrimination against queer women. Please tell us a bit about this.

JC: How does your gender intersect with your sexual orientation to form new and different kinds of violence and discrimination? But that’s an area of study that’s never been addressed, or even as a community we don’t address the issues around violence, because we’re all brought up to think that Singapore is very safe. But from our documentation it’s not true at all. A lot of it is behind doors or underreported.

THG: We’re not just talking about physical violence?

JC: Often it’s psychological, deprivation, like being beaten up by family or strangers. Or corrective rape and punitive rape. Essentially corrective rape only happens to queer women because men want to change your sexual orientation, but at the same time targeting your gender. A straight woman can only suffer from punitive rape as a punishment. So that’s something that queer women face that’s unique. The issue around domestic violence is quite serious actually.

Essentially how society punishes women that are different. For example, if you’re talking about single women, single mothers, how do our policies punish them? So women who don’t fit into that stereotype, or the state-sanctioned type of women, they are often punished. And in the same way, LBTQ women don’t fit into that state-approved, or society-approved model, so how does the community punish them, how does our culture punish them. You can see that manifestation.

THG: Those in power might reject that word ‘punish’, because they don’t see it as punitive, but as supporting and encouraging a certain kind of society.

JC: So that is [encouraging] conformity. But if you’re an unwed mother or single mother why is it wrong? It’s your choice. Why does society feel like they have a stake in what you do? And it only happens to women. Society decides, ‘Oh we can’t have an abortion.’ But why? Nobody tells a man what he can or cannot do. So a woman’s body is being regulated. Culturally, historically it’s always been like that. So how do LBTQ women fall into this category? That’s where the intersections happen with gender and sexuality and how it merges and creates new and different kinds of discrimination and violence.

READ: International Women’s Day: Abused but Unbeaten

THG: As you discovered, having the right language is so important in also understanding the violence and discrimination that queer women face.

JC: The first thing to empower yourself with is language. For example, when we did the violence and discrimination documentation against LBTQ women, we found that a lot of people don’t know what’s happening to them. They don’t have a language to describe violence and discrimination. So they will say, ‘Yeah, my life is like that. It’s normal.’ They don’t know how to explain. They have no framework or language. So when we did the research, we have a certain framework around violence. It’s to enable people to find a language to explain this is what’s happening to me. I think the key is to explain it in a simple way. That’s always a challenge so that people can relate and can use the language.

THG: How would you assess conditions for the LGBTQ community in Singapore? What can be done to make it more equitable?

JC: Things have improved…we’ve made some progress in terms of society acceptance. If you look at the media, maybe 15 years ago, they will not even call you a ‘gay activist’. They will skirt around the issue. Even politicians will say that they [queer people] are just as equal as anybody else. But of course, in terms of law we are not equal.

So we still have a long way to go. There’s a lot of people who don’t accept us [yet], which is the majority. But other than [repealing] Section 377A [of the Penal Code], we should be looking at some of the policies and ask for change. Ten years ago, the conversation is about gay men suffering a lot. Only gay men suffer because the law is visible. So when we did the research two years ago, we made a point [to show] how violence and discrimination is hidden for LBTQ women. It’s not that we don’t suffer, or who suffers more. It’s that we all suffer differently.

[We also need] the right to healthcare, anti-discrimination and the right to housing. These are some of the things that we can definitely work on that will improve the lives of LGBT people. We were the generation that will till the ground, but I don’t think we will be able to harvest it.

THG: What are the various forms of discrimination the LGBT community face?

JC: For a queer person the first thing you learn is that the world is hostile. When you’re going out into the world you often do mental calculation. Who is friendly? Who is not? And you’re sensitive. You gauge people that way. And Singapore society is still hostile especially if they find out you’re queer. The biasness is very insidious.

For queer women, there is also the issue of patriarchy, sexism [in the community]. A lot of LGBT movements not just in Singapore, worldwide, are gay men focussed and controlled. The narrative is centred around the gay experience but hardly around queer women’s experiences.

Then as a queer person growing up, it’s the constant messaging from the public, the media, and people around you that there’s something wrong with you. Or you’re a paedophile. They don’t have to accuse you. You [only] have to watch TV or listen to your pastor on the pulpit. The constant messaging in society, it’s a source of mental illness for a lot of LGBT people. So, a lot of us grow up having to prove ourselves. We have to be better because people are telling us we’re not good enough. We’re not good enough to be equal citizens or equal human beings. A lot of LGBT people when they’re old, and they’re vulnerable, they go back into the closet. Especially if they have to live in a [nursing] home. You can’t protect yourself anymore, you will have to rely on people. You’re afraid of bullying. People can do things to you, or they can try to pray over you.

READ: International Women’s Day: Paving the Way for Sex Workers’ Rights

THG: Why do you continue to risk your safety to advocate for LGBTQ rights?

We all take risks. Over time you get desensitised to it. In many public spaces the more you don’t pass as what a woman should be, the more that kind of aggression comes. So that makes me angry, I feel we should talk about it. I have documented androgynous, lesbian women getting molested in public. People feel like they can have a go at them which is sad.

But why do I take risks? Anger I think. Why should we suffer? Why should people come up to me and threaten me, I didn’t do anything to you. And then I think as a queer woman I grew up with no role models. I never had anyone who I could look up to or who I could ask questions. That’s why I say a lot of the founders of groups, around my age or late 30s, grew up with a sense that we want to create something that we never had. I think that was what drove many of us. Sayoni… wants to shape discourses, we want to shape how people talk about some of the things that’s happening to us.

THG: You talked about starting conversations. How do you bring straight, often ignorant people, and the queer community together to deepen understanding about LGBT issues?

JC: That’s where coming out with the family matters. But of course, come out when it’s safe. Don’t come out and get beaten up or something. And then come out with friends that you feel safe with, your best friends. The younger generation, who are much more influenced by the media, are much more open than us [her generation]. Even some of them who are not queer, they say, ‘My pronoun is…’ So they’re actively already doing it [having conversations]. Things will keep changing. It’s whether you and I can see it.

Younger LGBT people are more confident. They come out and say who they are. That helps their friends, who are exposed from young, [understand that] these people are human beings, so what’s wrong. But when you don’t know anyone [who is queer], maybe they have horns or they’re like the devil.

But young people know that things are not changing here. We did a focus group discussion with kids 18 and below. About 80, 90 per cent say they want to migrate. I don’t think it’s a sad thing. It tells me that they’re exposed enough to know that they want a different life, and they will leave to pursue that different life. It also means that they have information that I never had. So I think it’s a good thing. Of course, we’ll lose them. Singapore has to pay a price. But I think it’s good for them as human beings, where they want to strive for happiness.

THG: What would a utopia look like for queer women?

JC: For myself, I don’t have to do anything anymore. I’ll move on to work in other countries. For the community there’ll always be issues to address, but essentially, to feel safe. That women who have been attacked, raped, corrective raped, could go to the police and feel safe. And not like if I go to the police I have to tell them I’m gay.

I think utopia means we have all the rights, like everybody else, like a citizen. Now we don’t, we are like second-class citizens, sometimes third class.

READ: International Women’s Day: Single Motherhood A Chance to Turn Her Life Around

THG: A lot of corrective rape of queer women go unreported. Why?

JC: Especially if you’re not out. Like this girl when she came out, her brother’s friend raped her. When she went to her parents, her parents blamed her. ‘Yeah, why you tell people you’re lesbian, you deserve it.’ She’s left Singapore, but that reinforced that we don’t have that support. Because for a rape victim to report it takes a lot of strength. You need friends and your network to support you, when you don’t have that it is very difficult. And for a lot of LGBT people, sometimes they are not out, you have to explain a lot… jump through many hoops. So that’s why there’s under-reporting. And maybe for trans women, they don’t go to the police, they are more afraid of being ridiculed or not taken seriously.

The main obstacle for victims of violence, whether it’s rape or family violence is coming out. That’s the number one obstacle. And then trust in the agencies is not there.

Already for women to report rape is such a shameful thing. If you’re queer, or if you look very tomboy like me, it’s even harder. There was a case, somebody’s friend that I met, this butch, she was raped by a gang of men. She went to the police who looked her up and down and asked, ‘Are you sure or not, you look like a man?’ She dropped the case.

THG: Because sexuality plays such a big role in your life, how does this intersect with being a woman? And where does this fit in with gender equality?

JC: For Sayoni we talk about feminism, where the idea about gender is that it is a social construct. This is super relevant to LGBT people, because when I give talks, I always ask the question, ‘Did you become a woman or were you taught to be a woman?’ How society constructs gender affects all of us, especially LGBT people. And, it’s not just about LGBT rights it’s very closely linked to gender equality.

In East Asia they celebrate female masculinity, women can be masculine too and you can be feminine as well. So you identify with what you’re comfortable with, because your gender expression is on a spectrum. In Singapore women can have short hair, but if you go to the Middle East this is seen as a very masculine thing. I get misunderstood so I understand. I think it’s okay to have this diversity of gender expression or sexual orientation. A lot of women are bisexual. Nobody’s 100 per cent straight or 100 per cent gay. Young people are embracing it, they’re saying I’m non-binary because I don’t want to fall into your social construct of what a woman is. I want to celebrate the masculine side of me too. So are you just your genitalia or more than that?

THG: But when you celebrate your masculinity isn’t it still a social construct?

JC: True. There was a famous feminist who said instead of man, woman, why don’t we say we have a gender 360? We are all complex human beings. And it’s okay to be different. We’ve not said this enough in Singapore. If you want to present yourself in a different way, you’re not doing anything wrong. But the policing of that expression is a very real and problematic thing. Of course, sexual orientation is another discussion.

THG: What advice would you give to queer women who are finding their voice and carving out a space to live and express their truth?

JC: Ensure safety. Keep on telling your stories… because people change their minds when they know somebody. And keep being who you are, keep staying true to who you are. We have so many pressures to conform in Singapore, we’re quite conservative as a society. I think I live in a bubble. So my friends are quite open-minded generally.

I came out to my sis about 10 years ago and she’s Catholic. We were having a fight and she was like, so what I don’t care, as long as you’re a good person. My brother and my sister-in-law are quite accepting. But we don’t talk about it. My mother is always referring to my girlfriends as “your good friend” (ni de hao pengyou). Or if I bring a new girl home, she’ll keep talking about my ex. She’ll ask hey where’s that… And I’m like shut up. (laughs)

My family’s quite traditional and a typical Chinese family. There’s no big expression of love, [it’s] unspoken. This Chinese New Year we were talking about zodiac signs. My nephew, he’s only six-and-a-half, paused and asked what my wife’s zodiac sign was. I almost spit out my pineapple tart. I was stunned. So probably his mother [sister-in-law] [explained] things to him. When she sees me in the papers, she’ll cut it out and show it to my parents. She doesn’t say I’m an LBT activist. It’s not Westernised with a big declaration, ‘Okay, I accept you.’ Perhaps [mine] is an Asian family form of coming out. Also, my mum is in her 70s, she grew up not having a context about what it means to be LGBT. As long as I’m a good person. I think that’s critical for me.

READ: International Women’s Day: Living Life Unapologetically Without Hands

THG: The theme for IWD 2021 is #ChooseToChallenge. What would you challenge in terms of being a queer woman?

JC: It’s to challenge your reticence of not speaking up. Your own silence. To speak up when you see a woman being harassed in a bus, for example. When you speak out it really helps. I think people don’t know how. So sometimes when I see a guy slap his girlfriend on the street I’ll pause and look so that they become conscious of me. But then how do we speak out in a way that does not do more harm? Because sometimes you scold them and they go to another place and the girl gets whacked, or the domestic worker gets worse [treatment]. I feel like we need more of such conversations. How do we speak up against homophobia, sexism and violence in a way that immediately empathises with the victim and de-escalates [the situation] at the same time? How do I help without causing more harm?

So I choose to challenge my own silence. I struggle [with this], as well. I’m not perfect.

Join the conversations on THG’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.