As part of the 2021 Singapore HeritageFest, community arts group 3Pumpkins invites us into the homes of six children and youth living in a housing estate in western Singapore, for a taste of their cultural heritage documented through the food that their caregivers cook and the mealtimes they share as a family. These stories were captured by the children through photography and culminated in the exhibition, This Is What We Eat At Home.

Orh bak (braised pork) or fried rice? These were the two dishes 13-year-old Lucas Lee had shortlisted to showcase in a community arts project called This Is What We Eat At Home. The former he would have to learn from scratch from his great-grandfather, the latter he cooks regularly for himself. Lucas turned to his mother to help decide – she picked orh bak.

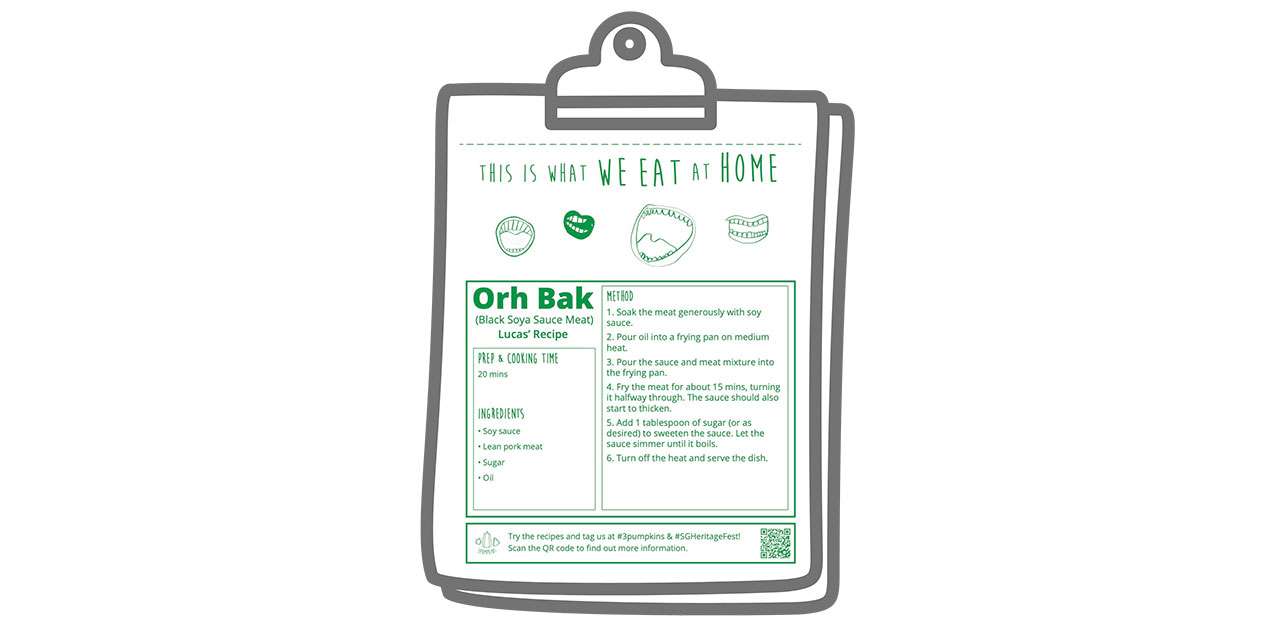

“When I’m young, my great-grandfather cooked this dish. And I think that is very nice, that’s why I use orh bak… in this exhibition to show other people,” explains Lucas. “Orh bak is called ‘black meat’; direct translate… So it’s like a lot, a lot of dark soy sauce to make it have gravy. But if you put too much dark soy sauce it’s very salty. That’s why, put sugar to balance. So you make it sweet, but watery [with sauce].”

Lucas is one of six children and youth who participated in This Is What We Eat At Home, which was organised by non-profit community arts company 3Pumpkins, as part of this year’s Singapore HeritageFest.

The participants are members of 3Pumpkins’ Tak Takut Kids Club, an arts-based youth centre located in Boon Lay, a public housing estate in western Singapore. Their families were paid an honorarium as an incentive to take part, since many come from low-income backgrounds.

Founder of 3Pumpkins Lin Shiyun says that they have been engaging the neighbourhood’s kids since the centre opened in 2019 but wanted to meet the parents and relatives. They preferred to do it in a way that was “more natural” than knocking on doors, which is “very social service work” and not a route they wanted to replicate.

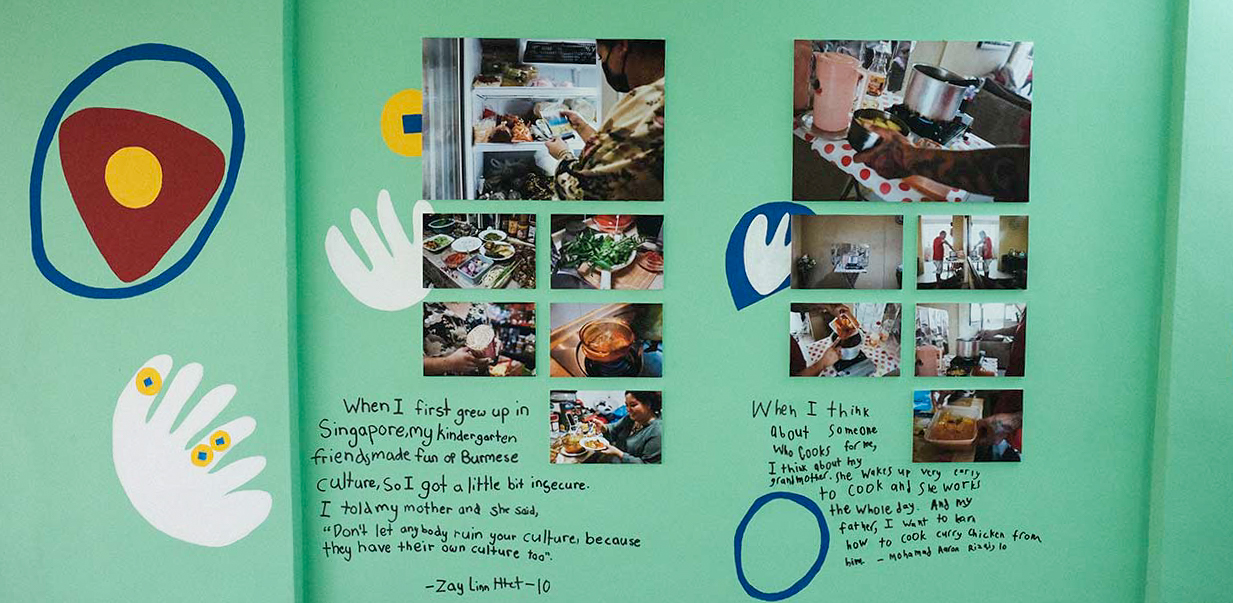

Ms Lin also shares that the project was motivated by 10-year-old Zay Linn Htet, a Burmese who was teased and bullied a lot growing up in the area, because he is a foreigner. She had first met Zay and his sister at the Kids Club, where they had declined to tell her where they came from, because they were “embarrassed about it”.

“That was something that stuck with me and I always wondered how we can address that issue?” she says.

The “Eureka moment” arrived when the National Heritage Board approached her to join the festival this year. She realised that through the sharing of food heritage they could address the lack of understanding among residents about their multicultural backgrounds.

Elaborates Ms Lin, “At first, we wanted Larry (the mentor photographer) to document them [participants] cooking with their caregiver. But, after thinking, I feel that in that sort of creation process, usually the artist gains a lot of knowledge… then all this stays with the artist.”

After much thought, she decided that the child would be the artist instead, and they would photograph their family members: “So they have the distance to observe and they are also the one who organises the knowledge… It’s a platform for them to create these memories, because also that is probably not something that they do.”

She adds, “It’s very important that the first impact is for the community; like the participants and their family. How does this project benefit them?”

Photographer Larry Toh guided the children on how to use a camera to document a family member cooking a dish and/or them eating together at mealtimes. The tactile journey culminated in a physical and online exhibition with photographs, audio elements and other forms of recorded heritage, like home-cooked family recipes and food journals.

Mr Toh says that he did not know what to expect at the start of the project: “They were all very different, but one thing in common was that they seemed very sure of who they are as individuals. I tried thinking back on how I was when I was their age, and could not remember myself being so sure of myself.”

A rich and complex community in western Singapore

According to Ms Lin, many of the children in the area come from families on social assistance; single-parent households; or homes where one or both parents are incarcerated or are working, and are, therefore, hardly around. In such cases, the children’s often sickly grandparents become their primary caregivers. A substantial number of families are also permanent residents (PR), like Zay’s, and transnational, with a dual-Asian heritage.

“There’s a lot of mixed-Vietnamese here. So usually, their father is in the late-50s, Chinese Singaporean, and they have a much younger mother, Vietnamese,” she says. “So coming from this sort of family, the kids can be quite confused about their identity.”

She explains, “For instance, the parents speak only Mandarin or Vietnamese. And the children because they don’t spend much time with their parents, they spend a lot of time growing up on YouTube, they only speak English. So the whole family cannot communicate.”

In Lucas’ case, his parents divorced when he was seven and he lives with his mother. While he visits his extended maternal family on weekends, he mostly takes care of himself, an only child, while his mother is out working during the day to support them.

“My mother always works and my house, no people. So my mother teach me how to cook scrambled egg. Yeah, then slowly I watched YouTube, then I learn how to make fried rice,” he says, sharing that he started cooking in primary school and considers becoming a chef one day.

Having handled this level of independence from a young age, Lucas comes across as much older than his years. He even juggles a part-time job at McDonalds to earn extra pocket money: “I’m the youngest there,” he says. “All the managers treat me well.”

Lucas is also the youngest on his mother’s side of the family, which consists of four generations, and his maturity is apparent: in the way he talks and carries himself, as well as how he readily admits that he prefers spending time with older people. For instance, the ‘auntie’ co-workers at McDonald’s, or the 50-year-old volunteers of the Kids Club, whom he spends hours with playing the game Rummy-O when they visit the centre.

“Yeah, I’m very ‘uncle’. I’d rather talk to aunties like about 50-plus than talk to [people] about 20-plus,” says a smiling Lucas. “My friends always call me ‘very uncle one’ – I go out must bring umbrella.”

For this project, he photographed his 90-year-old great-grandfather cooking the orh bak dish, revealing that the elder patriarch used to be a fishmonger and had recently had a stroke.

Lucas also recorded the recipe as passed to him by his great-grandfather, and says the cooking session was not without its hiccups: “One of the challenges like he slowly got dementia. Then that time forget to add sugar, he keeps saying ‘I got add sugar’, ‘I got add sugar’. So everybody say ‘haven’t add sugar yet’… In the end boh pian (‘no choice’ in Hokkien), never add sugar… just eat like that.”

Documenting the food heritage of multicultural Singapore

Overall, it seems the project has achieved what it set out to do, which was to open the doors to the homes of residents, and record the food heritage of these six participating families. It also encouraged the participating children to learn about their cultural heritage, deepened their connections with caregivers, which in turn might help to shape their identities and sense of belonging, says Ms Lin.

Besides Lucas and Zay, the other participants were:

- Ariel Nour Nadeera Ishika, 15, whose grandmother had a stroke and stopped cooking for the family. Now they mostly da bao (Mandarin for taking away food).

- Mohamad Aaron Rizai, 10, whose grandmother cooks first thing in the morning before she starts work. But it was his father from whom he wanted to learn how to cook chicken curry.

- Muhammad Sulaiman, 9 and Sakthivel Shoban, 13.

Says Mr Toh on spending time with the children and their families: “I felt welcomed by all the families involved in the shoot. They opened up their homes. We shared food and traded life stories. I enjoyed watching how the kids documented the cooking and the food, and nudging them to change perspectives.”

He adds that although each family has a different background with varying cultures and privileges, they each have a “source of pride and happiness”.

“Learning about the family stories and history was a very memorable thing for me,” he says. “Maybe because as a child, I had always enjoyed listening to my parents and grandparents reminisce the old days and imagining how it was to live during their time.”

People outside of the community have also been touched by what the children have shared about their families, and have had similar food-related memories of their own.

Given the success of This Is What We Eat At Home in engaging the community, Ms Lin is already considering a second edition of the project: “We do have some other kids [whom are] also very inspired. And they were a bit jealous, [asking], ‘How come these six people had the job and we are not selected?’,” she says.

“Then I also started to know more caregivers during this period of time. And I think there are probably another six who would be good for them to participate in this,” she shares. “So I hope this is something we continue and we can have a collection and publish a book.”

[Note: Due to the tightened restrictions, 3Pumpkins has moved the exhibition This Is What We Eat At Home fully online.]

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.