That it is possible to earn a living from livestreaming, would likely be unfathomable to those unfamiliar with the scene.

That was how JoAnne Chen felt before she became a full-time livestreamer on Bigo Live three years ago, entertaining her audience by singing, dancing and conversing with them.

The popularity of livestreaming has exploded since the start of the pandemic. In April, Coresight Research projected that the market for livestreaming was expected to reach US$6 billion (S$8.1 billion), this year.

With movement restricted by Covid-19, many have turned to the internet for leisure and pleasure, and a major source of entertainment has come from livestream hosts.

Through livestreaming, hosts broadcast themselves playing video games, singing, dancing, cooking or simply having a chat with viewers, through platforms such as Bigo Live, Ele Live, Facebook Live and Twitch. Viewers may interact with livestreamers in multiple ways, one being to send virtual gifts that can be cashed out for money.

When told that viewers could send virtual gifts on livestreams, Ms Chen was incredulous: “I didn’t even believe that [gifting] would happen. This is another generation kind of thing,” she chuckles in disbelief.

But such is the case on some livestreaming platforms. For M (not her real name), a livestreamer on Ele Live, the largest gift she has received amounted to 13,140 Elecoins, costing at least S$230 (US$169) in real money terms.

Spending on virtual presents might not strike many as rational behaviour, but tips received on livestreaming platforms reached a whopping US$101 million in 2017, a 25 per cent increase from the previous year. This willingness of viewers to spend money on virtual gift-giving, subscribing, donating and other similar acts begs the question: What is there for viewers to gain out of this?

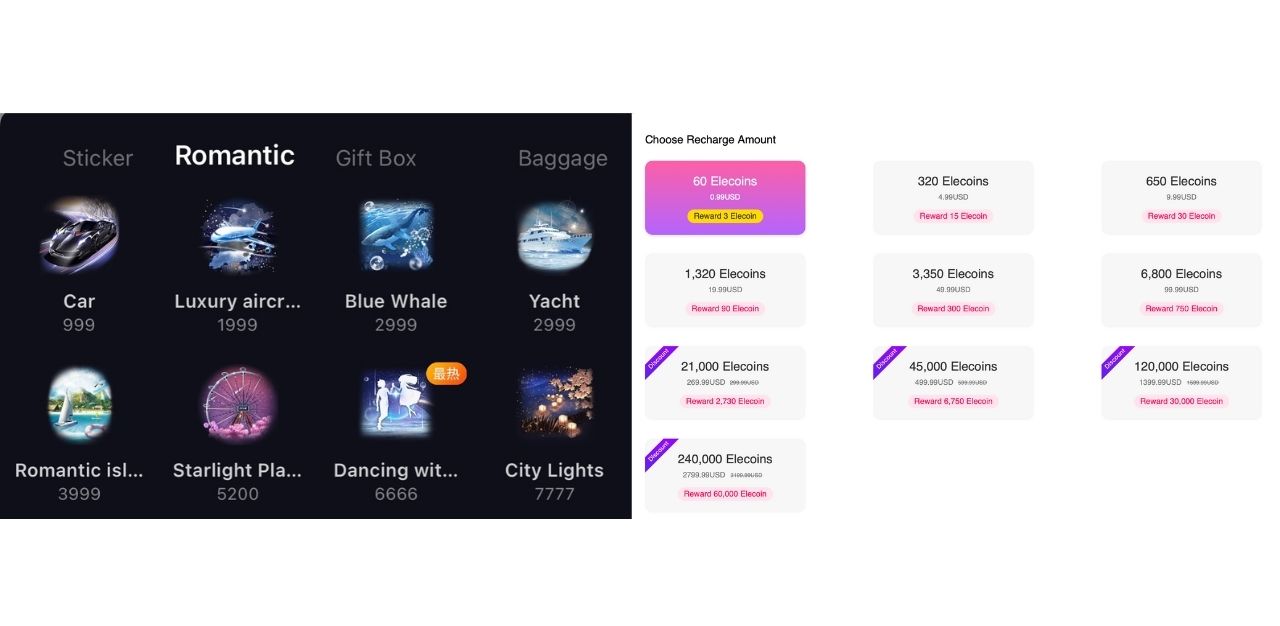

On Bigo Live and Ele Live, viewers may purchase anything from a rose for a few cents, to a yacht and even a dragon for tens or hundreds of dollars.

On Twitch, viewers do the same using a virtual good called ‘bits’. Other features to the same end include viewers subscribing at a monthly minimum of S$6.75 (US$4.99) at the lowest tier, gift subscriptions to other viewers and direct donations. On Facebook Live, virtual goods are called ‘stars’. For every Twitch bit or Facebook star, live streamers receive S$0.014.

Different livestreaming platforms also have different markets. For instance, Ele Live, a popular platform in the SouthEast Asia region, is highly gendered where the majority of the livestreamers are female, and viewers are male. While global platform Twitch is known for its gaming content, the Just Chatting category has ranked as the most watched livestream content since last year.

Psychology of virtual gifting

“Supporting streamers through donations is one of the main reasons viewers engage in virtual gifting,” says Associate Professor Vivian Hsueh Hua Chen from the Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information at Nanyang Technological University, in Singapore.

Associate Professor Chen specialises in media psychology, which examines the relationship between media and human behaviour. One of her research interests examines the social and psychological impact of new communication technologies, such as virtual reality, augmented reality and video games.

Livestreamers whom TheHomeGround Asia interviewed agree with Assoc Prof Chen.

“There is no other way for them to show their support, [besides] by liking [and] sharing the stream,” says Nauman Pasha, 32, a full-time livestreamer, known as @rebelssquadcsgo on Facebook. “It is one of the ways for viewers to express how much they like you and how much they appreciate the content you’re creating at the moment, right?”

He adds, “They also understand that we are putting our time sitting here, doing all the effort to entertain.”

Livestreamers, like Bernice Koh, 24, also use the gifts they receive to improve their livestreams. The talent with EMERGE Esports currently works in human resources, but aspires to become a full-time livestreamer, and spends the money on more stream content that her viewers can enjoy, such as purchasing games to play. Known as @Grappyzxc on Twitch, she streams herself playing a genre of games, including puzzles and first-person shooter video games.

Virtual gift-giving is also motivated by the viewers’ desire for attention, and to be recognised by their favourite streamers, particularly those whom they feel more emotionally attached to, says Assoc Prof Chen.

M concurs, noting that most viewers “give gifts for a kind of response”.

As any serious livestreamer would say, interacting and engaging with viewers are key to gaining an audience. This study finds that when viewers enjoy and find satisfaction from livestreams, this creates viewer loyalty towards livestreamers, which is in turn positively related with the intention to follow and donate.

Gifts, subscriptions and other donations are also often announced on-screen through animations and custom visuals. In turn, livestreamers would acknowledge viewers’ gifts and donations by reading out their usernames and thanking them.

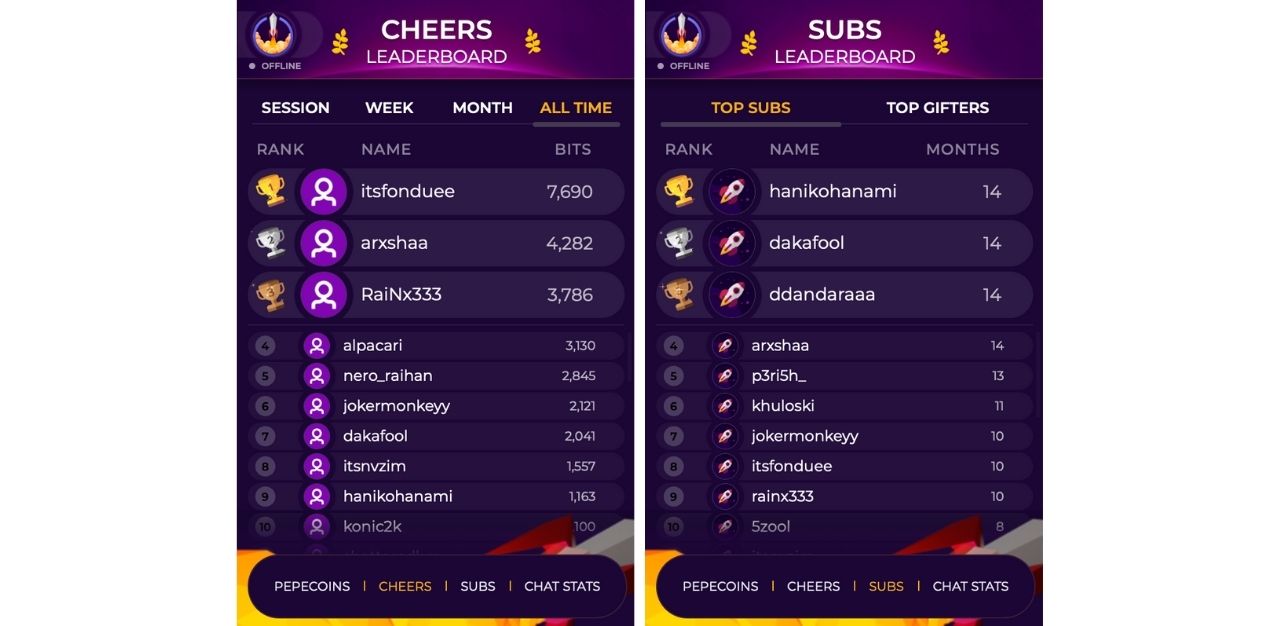

Leaderboards are frequently used to rank daily, weekly, monthly or all-time high donations from viewers, which Assoc Prof Chen says “gamifies the stream and drives some viewers to compete for places at the top.”

She points out that the exchange of money for recognition is also exemplified in the recent trend of individuals with bigger online audiences donating large sums to those with smaller audiences. Recording and uploading videos out of streamers’ candid responses of surprise, shock or confusion to a sudden donation and surge in viewership, can be seen as another form of “transacting recognition,” or exchanging of money for recognition.

Crucially, the sense of mutual interaction when streamers read viewers’ messages and acknowledge their donations may “[develop] a stronger emotional connection from viewers to streamers,” says Assoc Prof Chen. This in turn influences viewers to be more willing to engage in gift-giving, and the cycle repeats.

Virtual gift-giving is also blatantly encouraged in events such as Player Knock-out (PK) Battles on Bigo Live and Ele Live, whereby one streamer is pitched against another in a competition of who receives the largest amount of gifts from viewers. A near equivalent on Twitch would be the hype train, where viewers keep the train going for as long as possible by subscribing and cheering with bits within a limited timeframe.

On why viewers are willing to pump money into these events, Ms Chen, who has taken part in PK Battles, suggests that it is a form of the community rallying support for the streamer: “Sometimes, they know that if we lose [the battle] quite badly, they can see the disappointment in our face.”

Livestreamers play a role in virtual gift-giving too. A recent study found that gift-giving behaviour is positively influenced by certain traits of livestreamers. Those deemed trustworthy and attractive, in terms of physical and inner moral traits that appeal to users, stimulate feelings of emotional attachment in viewers, which in turn motivate them to purchase virtual presents.

This is echoed by Mr Pasha, who acknowledges that apart from watching his gameplay, “most of [the viewers] come because of you [and] your personality.” When he watches others’ livestreams, he muses: “To be honest, sometimes I don’t know what’s going on in the game, but I like the person, I like to chat with them and when they reply, I feel good.”

Virtual gift-giving could simply be a visceral response too. When M uses Ele Live as a viewer, she finds that “there is really this temptation to give, [such as] when the streamer makes you very happy. It’s an impulse.”

One-sided or two-way?

‘How could we not get attached to someone like you?’ In response to a viewer’s question, popular Twitch livestreamer @ludwig with an audience of 2.9 million, firmly posits: “You shouldn’t form a relationship with me. At the end of the day, I’m entertainment. If I stop entertaining, you stop watching, that’s it. That’s what I want from you guys, because I am not your friend.”

The illusion of friendship with online personas one has never met is often used to describe and characterise relationships in the livestreaming arena. Termed ‘parasocial’, it was first coined in 1965 to describe one-sided forms of mediated interaction between audience and media characters, fictional or non-fictional alike.

While relations are often believed to be one-sided from viewer to streamer, is this true for all? What do livestreamers themselves have to say about the streamer-viewer relationship? When probed, most interviewees concur that they do think there is a bond shared with their viewers.

To Ms Chen, the bond is inexplicable: “You feel like, ‘Oh, this person is always there.’” Livestreaming is not only a place where she could be herself unreservedly in a supportive environment, where “people like us for being ourselves.” It is also a place where streamers and viewers might seek encouragement when feeling down.

Similarly, M notes that livestreaming is a place where viewers might share their troubles: “Some people came here with their hearts broken or [when they] lose their job, [and] they come here for comfort.” While M finds their forthcoming behaviour “a bit weird… because they don’t really know the person,” she understands that “it is easier to talk about problems to a stranger than to someone you’re close with.”

EMERGE Esports talent Amsyar Haziq Bin Zainal Abidin, 23, has set his sights on becoming a full-time livestreamer. Known as @AHBZA_GAMING on Twitch, he streams himself playing a variety of video games, such as Valorant and Apex Legends. He cites the example of one of his chat moderators, with whom he has built “a very massive bond” without having met each other in real life.

Initially a stranger who dropped by every stream, Mr Amsyar grew to trust and eventually made him a moderator of stream chats for spam and unwanted behaviour. This has also been the case for Ms Chen, who assigned some of her viewers to become stream administrators.

Livestreaming might be Mr Amsyar’s dream job, but it drew skepticism from his parents: “When I first started streaming, what do I tell my parents? That I wanted to play games?… Is this even possible, to stream, play games and earn money?”

Hence that lack of assurance and encouragement has contributed to a sense of mutual bonding and friendship with his viewers.

“It is really heartwarming to see everybody come together and be so supportive in a local scene, which is very, very tough [to find] in Singapore,” he says about his community, with whom he also interacts off-stream on Discord, a group-chatting platform.

The relationship with viewers may even move offline, as is the case for Ms Chen and Ms Koh. Both had organised meetups with their subscribers. Ms Koh felt safe and comfortable meeting them offline on what are called ‘sub-outings’, as “they’ve been with my stream for a long time, about one to two years.” In fact, some have become her close friends in real life.

For Ms Koh, she also makes the effort to remember details that viewers have previously shared with her about their lives, much like you would do with friends. As such, she notes that her channel has a high retention rate, whereby the average subscriber has been with her for at least six months.

Mr Pasha even hopes to achieve a vibrant and interactive gaming community for youths who are interested. With a rented studio in the works, he is prepared to invite viewers who lack access to streaming gear, are curious about or unsure of whether to pursue livestreaming, down to the studio “so I can show them how [livestreaming] works”.

Out of a decision to focus on enjoying gameplay and interactions with anyone who visits his livestreams, Mr Pasha also removed the Facebook star leaderboard indicating his top supporters.

On his livestreams, he not only shares advice with viewers inquiring about how to start or make a living out of livestreaming, he also invites viewers to join in the games with him. “Whatever I have learned or experienced, I want to share with them that [livestreaming] can be done [as a career],” Mr Pasha says.

Each with their own reason for why they have started livestreaming, such as out of a love for content creation, for the flexibility to earn money, or simply having stumbled into it, most interviewees concur that viewers are the reason they stayed despite the challenges involved.

Consistency is commonly identified by interviewees as the biggest challenge to being a livestreamer, as having an unchanging schedule is important to the channel’s success. But, when streamers have a full-time job to balance, this commitment can be taxing due to the gruelling hours lasting from morning until night.

“Viewers are the main reason I do it,” says Mr Pasha. For a period of nine months, he livestreamed every single day starting from June, last year. At the time, he was working as a digital manager at one of the local SMEs, while livestreaming on the side.

Mr Amsyar, who is currently doing an internship, perseveres with the tiring schedule as he believes that he “owes” it to his viewers: “Because without them, I wouldn’t have the setup [and] whatever you see behind me,” gesturing to the bat-shaped neon light, and light panels to his right. “It is [all] thanks to them,” he emphasises.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.