Singaporeans are under pressure from work-related stress and are not dealing with it until it is too late. But the problem can no longer be ignored. Too much stress can lead to burnout, and an exhausted, unmotivated workforce can hurt the economy.

A survey of 1,013 Singaporean workers by software firm Oracle showed that nearly 7 in 10 Singaporeans found 2021 to be the most stressful year at work. The survey, conducted between July and August this year, also found that 3 in 5 Singaporeans struggled more with their mental health at work in 2021 than in 2020.

Another survey, conducted by Milieu Insight, a marketing research and public opinion polling company, showed that Singaporeans fared the poorest in terms of handling stress compared to other Southeast Asian countries.

The study also found that most Singaporean workers are reluctant to ask colleagues for help even when they are under severe stress, find it difficult to say no to more work when they are already overloaded, and only seek help when the stress becomes unbearable. The survey looked at a total of 6,000 respondents, 1,000 each from Singapore, Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and Thailand.

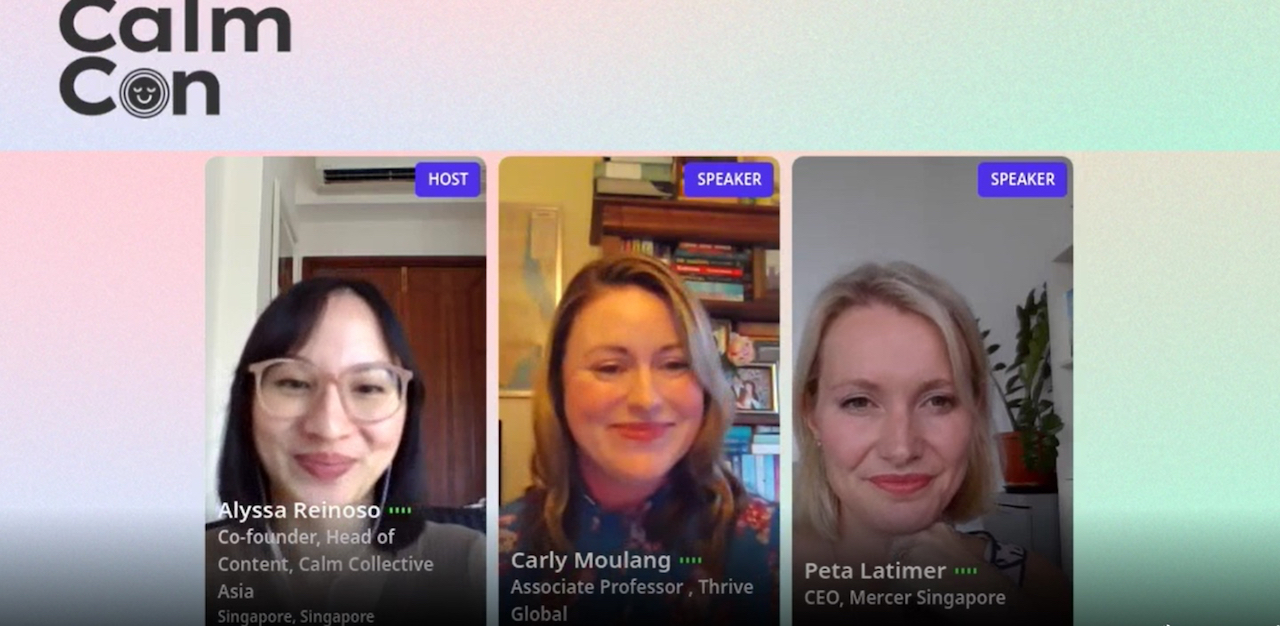

Research findings like these have sparked discussions among change makers, managers and workers who want to expand the space where everyone can feel safe while airing concerns about stress. Some of these conversations took place on the 12th and 13th of November during an online conference organised by Calm Collective, a social enterprise that aims to reduce the stigma – the level of shame and prejudice – experienced by people undergoing psychological difficulties in life.

Speaking up about stress

During a question and answer session at the live webinar, Milieu Insight’s CEO Mr Gerald Ang said Southeast Asians find it hard to say no to more work even when their to-do list is full, because they don’t want to be judged by their managers.

Expanding on the reason why, Ms Rachele Focardi, an expert on generational diversity in the workplace, says that Singaporeans’ reluctance to say no to more work has to do with the collision of conventional and progressive notions of work in the modern workplace.

“The general idea was that you have to take whatever is thrown at you and do whatever it takes to figure it out and make it happen. If you don’t, then there is the risk that somebody else will do it better and take over your job,” says Ms Focardi, who is chair of the Multigenerational Workforce Committee for the ASEAN Human Development Organisation, and founder of XYZ@Work.

“Until the millennials entered the workforce, the work environment was very cut-throat — in some industries or local organisations, it still is — with a lot of internal competition for the boss’ favour or for a promotion. Leaders often encouraged this and took advantage of it by pitting employees against each other to make them work harder. Employees were taught to always look confident and not show any signs of weakness; even asking how to perform a duty could make them look bad in the eyes of the boss, who usually expected them to ‘figure it out’,” she adds.

COVID-19 crisis puts more pressure on workers

Milieu’s findings come at a time when the world is in the grip of COVID-19. Work-related stress was already a problem before the pandemic. COVID-19 has intensified it further.

Work-related diseases and injuries were responsible for the deaths of 1.9 million people in 2016, according to joint estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labour Organization (ILO). Most of these deaths were related to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, with long working hours being the biggest risk factor and accounting for 750,000 of the deaths.

With governments instituting measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19, turning teleworking into the norm in many industries, the boundary between home and work has blurred. The WHO warned that the trend towards increased work time is accelerating and this has more people at risk of death and disability from overwork.

The “always on” work culture

The news is rife with reports of employees quitting their jobs because of stress from a work culture that requires them to be on call 24/7. Singaporean lawyer Nick Ng quit his job at a financial services company in March this year because his team expected him to be available all the time. Receiving constant notifications on his mobile phone caused heart palpitations and breathlessness that resulted in the 37-year-old seeking medical attention, says a report on the Nikkei Asia website.

A 31-year-old infrastructure development engineer, who wanted to be known only as Mark, told Channel News Asia he left his job after feeling mentally sapped and exhausted every day. Virtual meetings that dragged into the night and the constant intrusions into after-hours drove him to throw in the towel.

“Organisations that struggle with this kind of work-life integration, even though they have the policies in place, sometimes, do not actually do enough to make sure staff feel they can turn off from work,” says Dr James Goh, organisation development lead at the Halogen Foundation, a non-profit that trains young leaders and entrepreneurs.

Dr Goh explains that managers play a crucial role in shaping the work culture of their organisations.

“As a boss, as a manager, the power is almost in your hands to lead by example and do what’s necessary. So one thing, for example, I do when I communicate is, when I have something to send as an email in the evening, I will just draft the email first, but I’d choose not to send it until the next working day,” says Dr Goh.

Employees, too, have agency and can play a part in shaping company culture. For example, they can set boundaries on communication after working hours.

“When you set a time, be very disciplined and adhere to it. When you see an email (coming in at the end of your work day), don’t respond,” says Dr Goh, underscoring the importance of sticking to the boundaries one sets for after-hours communication.

Some employees stress themselves out by responding to managers’ after-hour emails and texts because they want to do their job well or impress their superiors.

“You think that by responding, people think you’re hardworking, that you are trying very hard in your work and doing really well, but the fact is, when you do your performance review, your managers won’t actually say ‘You sent emails at twelve midnight every single day and that’s why you worked very hard’. Most of the time they are actually looking at the quality of your work and how well you’re performing,” says Dr Goh.

Bosses aren’t superhuman either

Chief executives and managers are also workers, and like everybody else, they get stressed. These days they have to worry about the wellbeing of staff and business continuity in the context of a pandemic that is stoking an energy crunch, causing supply-chain bottlenecks, and driving inflation.

“I think first and foremost, leaders are not superhuman,” says Ms Peta Latimer, CEO of Mercer Singapore, a global management consultancy firm.

“As a leader you’re expected to manage P&L (profit and loss), you’re expected to have foresight, strategy, build the right culture, deal with operational efficiency, have individual approaches to people, and care about the mental health of individuals. I think we have to be very careful here because nobody is superhuman in all of these things. Each of us is on a journey. Each of us is hoping to improve ourselves as we go along, and leaders as much as anybody else need support,” she says.

Ms Latimer adds that leaders can reduce work-related stress by communicating expectations clearly, because burnout doesn’t necessarily come from doing too much. It comes from “being confused, and having all the pillars of your life thrown up in the air. The best thing that we can do as leaders is set far simpler, and clearer expectations”.

The Singapore government is taking steps to improve mental wellbeing at work. In November last year, the Ministry of Manpower (MOM), Singapore National Employers Federation (SNEF) and National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) issued an advisory on mental wellbeing at the workplace.

The document offers practical guidance on measures that employers can adopt to improve the mental health of staff. It includes a section on after-hours communication. One recommendation was: “Employers should set out a clear position for work-related messages (e.g. SMS, WhatsApp, Telegram) and emails sent after work hours, that a response is not expected until the next working day, except for messages/emails marked as ‘Urgent’.”

Some workers turn the table on the bosses

Efforts to nurture a culture that respects the mental wellbeing of employees should be counterbalanced with the need to manage workers who make unreasonable demands.

The Daily Mail Online carried an article saying that some Generation Z employees are scaring their bosses with woke demands. These include insisting that bosses show support for certain political causes, demanding paid time-off for anxiety, and assigning tasks to CEOs.

Gen Z-ers, or zoomers, are individuals born after 1996. The oldest members of this generation are around 18 to 25 years of age. They are the youngest employees in the workforce and will soon constitute a large proportion of it.

“Their uncompromising attitude towards practices that don’t reflect their values, and the fact that they prioritise their personal ambitions and ideals ahead of the corporate good, can make them appear rigid and entitled,” writes Ms Focardi in a commentary on Channelnewsasia.com.

But this aside, unreasonable demands can come from workers of any generation. From boomers to zoomers, anyone is capable of a sense of entitlement. The reason, however, for the concern about zoomers is the combination of digital savvy and social consciousness of this group that makes them effective at changing what they do not like in the world.

Ms Focardi writes: “Although they are often thought of as inexperienced, impatient, easily bruised and addicted to technology, Gen Z are sharp, mission-driven, fast-learners, champions for diversity, direct, and able to harness the power of the collective instead of trying to change the world alone.”

But zoomers lack the knowledge and experience, which their predecessors have, says Ms Focardi.

“Their drive, adaptability and humanity are exactly what our society needs. But in order to bring about the change they envision, they need the knowledge, experience and wisdom of those of us who came before,” she adds.

Generational diversity at work need not become a source of more stress. Instead, it is a cure for it. The broad-based support for a work culture where managers and workers respect each other’s boundaries can benefit from Gen Z’s drive to make the future of work inclusive, diverse and psychologically healthy.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.