Fill Me In

By now, we’ve become all too familiar with the deluge of COVID-19 updates that floods our feeds and front pages every day, but in recent weeks, another issue has been grabbing headlines across the globe. Namely, Australia’s News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code.

Touted as a world first, the landmark legislation, if enacted, would force tech juggernauts like Google and Facebook to pay local publishers and broadcasters for the news content featured or linked in search results and on social media. The proposed law is designed to sustain and support public interest journalism in the Land Down Under, and is expected to pass in the coming weeks after a debate in Parliament, with the outcome likely to make waves around the world.

What does the Code involve?

After years of light-touch regulation, in April 2020 the Coalition government tasked the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) with developing a “mandatory code of conduct” that would redress the conspicuous imbalance in power between digital platforms and media companies.

The result is the News Media Bargaining Code – released as an exposure draft in July 2020, introduced in Parliament in December 2020, and passed by the House of Representatives and the Senate earlier this month – which sets forth a negotiation framework that enables local news outlets to bargain either individually or collectively with tech gatekeepers over fair compensation for the inclusion of news content on services like Google Search, Facebook News and Instagram. The Code also states that if both parties are unable to reach a commercial agreement within three months, then the terms of remuneration will be decided by a panel of government-appointed arbitrators.

Furthermore, the Code stipulates that digital platforms must abide by a set of “minimum standards” that improves on the current status quo, such as appropriately recognising original content, giving at least 28 days’ advance notice of any changes to algorithmic rankings, and providing media businesses with clear information about the nature and availability of data collected through users’ interactions with news on their services.

Contraventions of the Code, including not bargaining “in good faith” during negotiation and breaching the minimum commitments, would incur a maximum penalty of AUS$10 million or the equivalent of 10 per cent of annual turnover in Australia. The aim of the Code is to level the playing field and allow a diverse news media sector to flourish.

Why is the Code necessary?

It is imperative that a law is put in place to ensure that public interest journalism does not lose out as Big Tech takes the lion’s share of advertising revenue away from traditional media. According to the ACCC, for every AUD$100 spent on online advertising, $53 goes to Google, $28 to Facebook, and just $19 to everyone else.

As such, the government believes that because digital platforms gain both users and dollars from news and analyses furnished by Australian media companies on their sites, it would only be right that tech titans should pay newsrooms a “reasonable” amount of money for their journalism. Moreover, the government has argued that financial support is needed to bolster Australia’s ailing news industry because a free, independent press is essential to social cohesion as well as democracy.

Who does the Code pertain to?

At present, the News Media Bargaining Code is set to apply only to Google and Facebook, although other digital platforms may be added in the future if there is “sufficient evidence to establish that they give rise to a bargaining power imbalance”.

On the flip side, news media businesses can participate in the Code if they operate primarily in Australia with the purpose of serving Australian audiences; produce and publish core news online (“core news” here defined as journalism on publicly significant issues); adhere to professional editorial standards; maintain editorial independence from the subjects of their news coverage; and exceed AUD$150,000 in annual revenue.

How did digital platforms react to the Code?

Not well, to say the least. In the six months since the draft code was published, Google and Facebook have been locked in a stare-down with lawmakers in Australia, with both tech firms vehemently opposed to the proposed pay-for-news legislation, going so far as to threaten to withdraw their services from the continent should the bill pass into law. The Australian government, however, has held its ground against the pushback, making only a few “clarifications and technical amendments” so as to improve the “workability” of the Code while still retaining its overall effect.

Commanding about 90 to 95 per cent of the search engine market share in the continent (and indeed, the world), Alphabet Inc.’s Google could cause a severe disruption in economic activity if it were to make good on its threat to pull out of Australia. Reacting to the proposed law back in January, Google Australia’s Managing Director Mel Silva warned the Senate Economics Legislation Committee that, in its current form, the News Media Bargaining Code is incompatible with how the internet functions and would set an “untenable precedent” for business and the digital economy.

“The principle of unrestricted linking between websites is fundamental to [Google] Search,” Silva said. “Coupled with the unmanageable financial and operational risk if this Code were to become law, it would give us no real choice but to stop making Google Search available in Australia.”

“News and journalism are a critical part of any democracy and we don’t disagree with that view,” Silva added. “[But] the free service we offer Australian users, and our business model has been built on the ability to link freely between websites – this is a key building block of the internet.”

“Withdrawing our services from Australia is the last thing that I or Google want to have happen, especially when there is another way forward.”

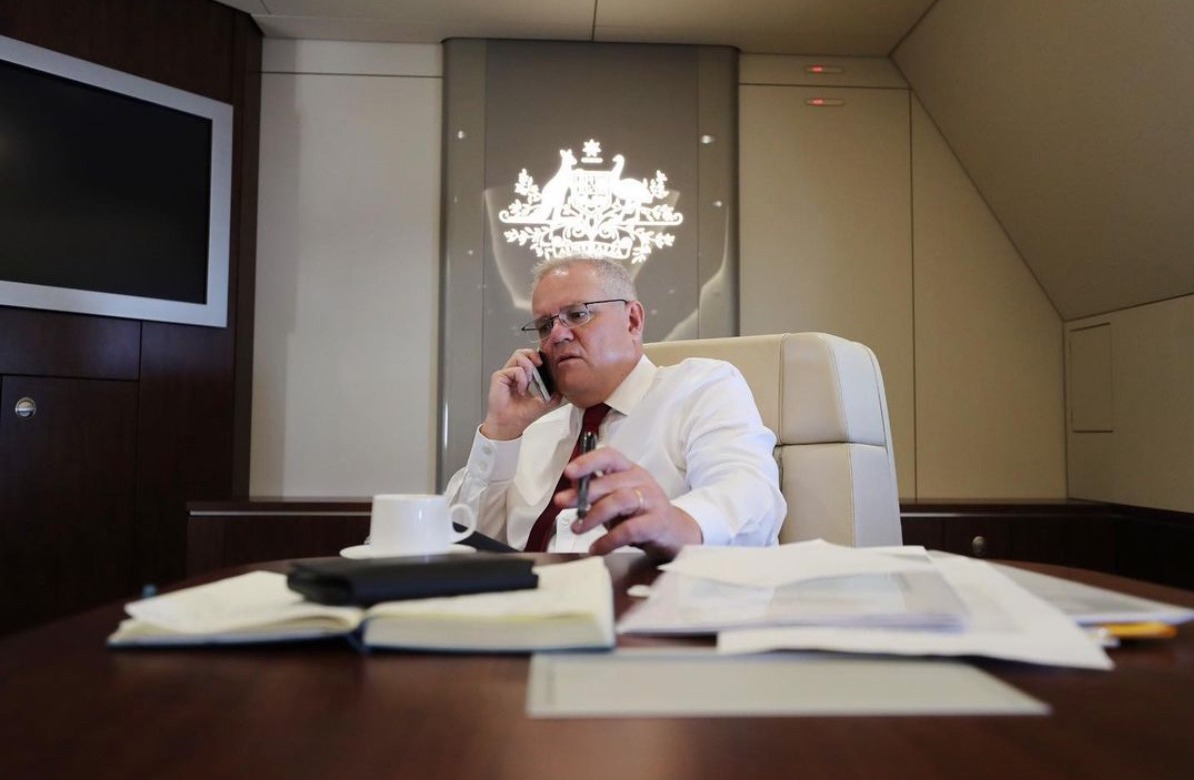

Prime Minister Scott Morrison fired back at Google’s ultimatum, saying, “Let me be clear. Australia makes our rules for things you can do in Australia. That’s done in our parliament. It’s done by our government. That’s how things work here in Australia, and people who want to work with that, in Australia, you’re very welcome.”

“But we don’t respond to threats.”

In the end, though, it was Google that blinked first. On February 4, Google announced the launch of its News Showcase product in Australia, a “licensing program[me]” that pays publishers to create and curate content for story panels across Google services, thereby offering readers greater insight into the stories that matter, while also helping publishers to develop deeper relationships with their audiences and to grow their businesses by driving “high-value traffic” to their content.

Since its initial launch in October 2020, alongside a billion-dollar global investment, Google’s News Showcase has attracted 400-plus publications across a dozen countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, Brazil, Canada, Japan and Argentina. Over the past fortnight, a growing number of Australian media organisations have joined the ranks, including Seven West Media, Nine Entertainment, Guardian Australia, Junkee Media, Private Media, and perhaps most notably, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, which owns two-thirds of Australia’s major city newspapers.

According to Treasurer Josh Frydenberg, who has been heavily involved in the discussions, Google’s eleventh-hour deals are the upshot of being “left in no doubt about the Morrison government’s resolve” on the matter, and serve as proof that the Code is already bringing about its desired effect.

Facebook, on the other hand, has taken an entirely different tack. In a dramatic escalation of its ongoing clash with the government, on Wednesday, February 17, the social media behemoth declared that it would block Australian users and publishers from viewing and sharing any news content, whether local or international, on its platform.

“We made an incredibly difficult decision to restrict the availability of news on Facebook in Australia,” wrote Campbell Brown, Facebook’s Vice President of Global Partnerships, in a blog post. “What the proposed law introduced in Australia fails to recognise is the fundamental nature of the relationship between our platform and publishers.”

“Contrary to what some have suggested, Facebook does not steal news content. Publishers choose to share their stories on Facebook. From finding new readers to getting new subscribers and driving revenue, news organisations wouldn’t use Facebook if it didn’t help their bottom lines.” Facebook also claimed that in 2020 the platform generated 5.1 billion free referrals that earned local publishers approximately 407 million Australian dollars.

The following morning, millions of Facebook users in Australia woke up to find that news content had been stripped from the platform, while dozens of pages belonging to government organisations, emergency services and charities had been disabled, affecting the Foodbank Australia, the 1800RESPECT counselling helpline, the Western Australia Fire Department, the Bureau of Meteorology and many more.

This snap decision sparked outrage across Australia. “Facebook’s actions to unfriend Australia today, cutting off essential information… on health and emergency services, were as arrogant as they were disappointing,” PM Morrison wrote on social media. “These actions will only confirm the concerns that an increasing number of countries are expressing about the behaviour of Big Tech companies who think they are bigger than governments and that the rules should not apply to them. They may be changing the world, but that doesn’t mean they run it.”

Meanwhile, Communications Minister Paul Fletcher told ABC that “Facebook needs to think very carefully about what this means for its reputation and standing.” Mr. Fletcher added that it meant Facebook would no longer be considered a reliable source of news. “We will be making the point that the position that Facebook has taken means the information that people see on Facebook does not come from organisations with a fact-checking capability, paid journalists [and] editorial policies.”

Various officials and lawmakers have also voiced their criticism of Facebook’s bare-knuckled tactics. Senator Sarah Hanson-Young tweeted that “Facebook blocking health information in the middle of a global pandemic is utterly irresponsible”, while Western Australia Premier Mark McGowan accused Facebook of “behaving like a North Korean dictator”. Others expressed concerns that a news vacuum could exacerbate the spread of disinformation, misinformation and conspiracy theories, for which Facebook has already come under fire.

Facebook blamed its blunder on the lack of “clear guidance on definition of news content” in the Code, and pledged to reverse the ban on the “inadvertently impacted” pages, with some accounts back up-and-running within hours.

Fiasco notwithstanding, it seems tiny steps forward have since been made, with PM Morrison announcing over the weekend that Facebook has “tentatively friended [Australia] again”, having returned to the negotiating table to try to iron out the snags with regard to the News Media Bargaining Code.

What happens next?

The Australian government is standing by the proposed Code. “We will legislate this code,” said Mr. Frydenberg. “We want the digital giants paying traditional news media businesses for generating original journalistic content.”

It isn’t set in stone, however. Once passed into law, the News Media Bargaining Code will be reviewed by the Treasury after one year to ensure that the practical outcomes are actually in line with the government’s policy intent – that is, protecting and funding public interest journalism, particularly independent publications, and not lining the pockets of shareholders or overseas parent companies.

Will other countries follow suit?

Although the Code is specific to Australia, there’s a very real possibility that other nations could follow Australia’s lead in standing up to Big Tech.

Canada, for instance, has already vowed to take up the gauntlet, with Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault in charge of crafting legislation along the same lines. “Canada is at the forefront of this battle,” Mr. Guilbeault told reporters a few days ago. “We are really among the first group of countries around the world that are doing this.”

Mr. Guilbeault also said he is in talks with his counterparts in France, Germany, Finland and more about working together to develop a suitable model for the fair compensation of online journalistic content. “I suspect that soon we will have 5, 10, 15 countries adopting similar rules,” he declared.

Microsoft President Brad Smith, on his part, has encouraged other countries (and in particular, the United States) to support and adopt Australia’s paid-content law. In a recent blog post, Mr. Smith highlighted that the tech sector carries an obligation to support independent journalism for the sake of democracy.

“In 1787, the same year Americans were drafting the Constitution, a leading British statesman reportedly gave the press its label: ‘The Fourth Estate’. Just as a chair needs four legs to remain sturdy, democracy has always relied on a free press to make it through difficult times,” Mr. Smith wrote. “Yes, Australia’s proposal will reduce the bargaining imbalance that currently favours tech gatekeepers and will help increase opportunities for independent journalism. But this is a defining issue of our time that goes to the heart of our democratic freedoms.”

“The tech sector was born and has grown because it has benefited from these freedoms. We owe it to the future to help ensure that these values survive and even flourish long after we and our products have passed from the scene.”

However, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the world wide web, has urged caution when it comes to enacting such legislation. In a submission to a Senate Inquiry on the News Media Bargaining Code, he argued that the proposed media law would not only “undermine the fundamental principle of the ability to link freely on the web”, it would also be “inconsistent with how the web has been able to operate over the past three decades”, and therefore, if other governments were to follow Australia’s precedent, it could make the web “unworkable” around the world.

Join the conversations on THG’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.