When it comes to informal caregivers in rapidly ageing Singapore, 3 in 5 of them are women, according to a 2012 government survey. From this study, 35 per cent are unmarried, and between the prime earning ages of 45 and 59.

Many have given up jobs or scaled back their hours as elderly parents’ needs grow. It is found that the average caretaker loses 63 per cent of her income or more than $40,000, according to a 2019 study by the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE).

Such statistics are something Ms Kris Foo is familiar with.

In 2014, the design consultant moved her office back home to continue her business while simultaneously providing care for her mother. Her mother is now in her late 80s and suffers from dementia, as well as depression and anxiety.

Ms Foo, who is in her 50s and unmarried, had to dip into her savings then and spent nearly $100,000 for her mother’s care. Her business began to taper and dry up when she worked from home.

“At one point, I had to borrow money to put food on the table. I started to worry about my lack of income for daily needs and for retirement, wondering who will take care of me. After 9 years of caregiving, these questions still haunt me,’’ she says.

‘’However difficult it is, I will do my best to take care of my mother. She spent her life caring for me, now it is my turn.’’

With Singapore’s rapid development over the past 50 years and a sharp decline in the fertility rate, the cost of caring for the substantial aging population today is falling disproportionately on women, many of whom are unmarried. They sacrificed careers and retirement savings to care for their elderly parents but have no children to do the same for them.

Steps to help

Singapore’s last known quantitative study on informal caregiving, conducted in 2011, found that most family caregivers of seniors over 75 were aged 45 to 59 – the prime age when most people are building savings for their retirement.

In early 2019, the Government announced some plans to enhance caregiver support. These include expanded respite care options and support networks, and a monthly Home Caregiving Grant of $200. All this represents a welcome step forward. Yet informal care is an issue that calls for bigger strides.

Today, there are no statutory requirements for companies to provide family care leave, though government initiatives encourage employers to offer unpaid caregiving leave. This is important but leaves the financial burden of caring on the shoulders of the caregivers.

The Government also provides financial incentives to companies to offer flexible work arrangements to help caregivers balance work and caregiving responsibilities. Although a crucial first step, in the country’s culture of presenteeism and emphasis on facetime, many employers still base worker appraisals on their physical presence in the office.

Finally, the various measures in place to offset care-related expenses do not compensate caregivers for the loss in income and retirement savings that often accompanies the provision of care.

Singapore’s traditional emphasis on the family as the first line of support has put the major responsibility for caring for ageing parents on their children.

When the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE) did a year-long research project studying the impact of family caregiving on caregivers’ retirement adequacy in Singapore, they were surprised to see that the predominant caregivers for ageing parents were unmarried women with no children, usually unmarried daughters.

Ms Shailey Hingorani, AWARE’s Head of Advocacy & Research, said that the trend is worldwide and most of the caregivers who were interviewed for the study, which was published in CNA in 2019, stated that they had to assume the role of the caregiver because of their gender and unmarried status.

‘’If they have siblings who are married, the married siblings are usually excluded from active caregiving duties because they have families of their own to look after. But since the study was done, more married children are becoming caregivers for ageing parents. I believe that this is due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the resultant economic disruptions, which have forced family members to have to come together and share caregiving duties. But the proportion of married parental caregivers is still a smaller percentage compared to the single ones,’’ she says.

Now with singlehood and smaller families getting more common, “relying on children as caregivers may not be feasible”, says Professor Paulin Straughan, director for Singapore Management University’s Centre for Research on Successful Ageing.

This man gets it

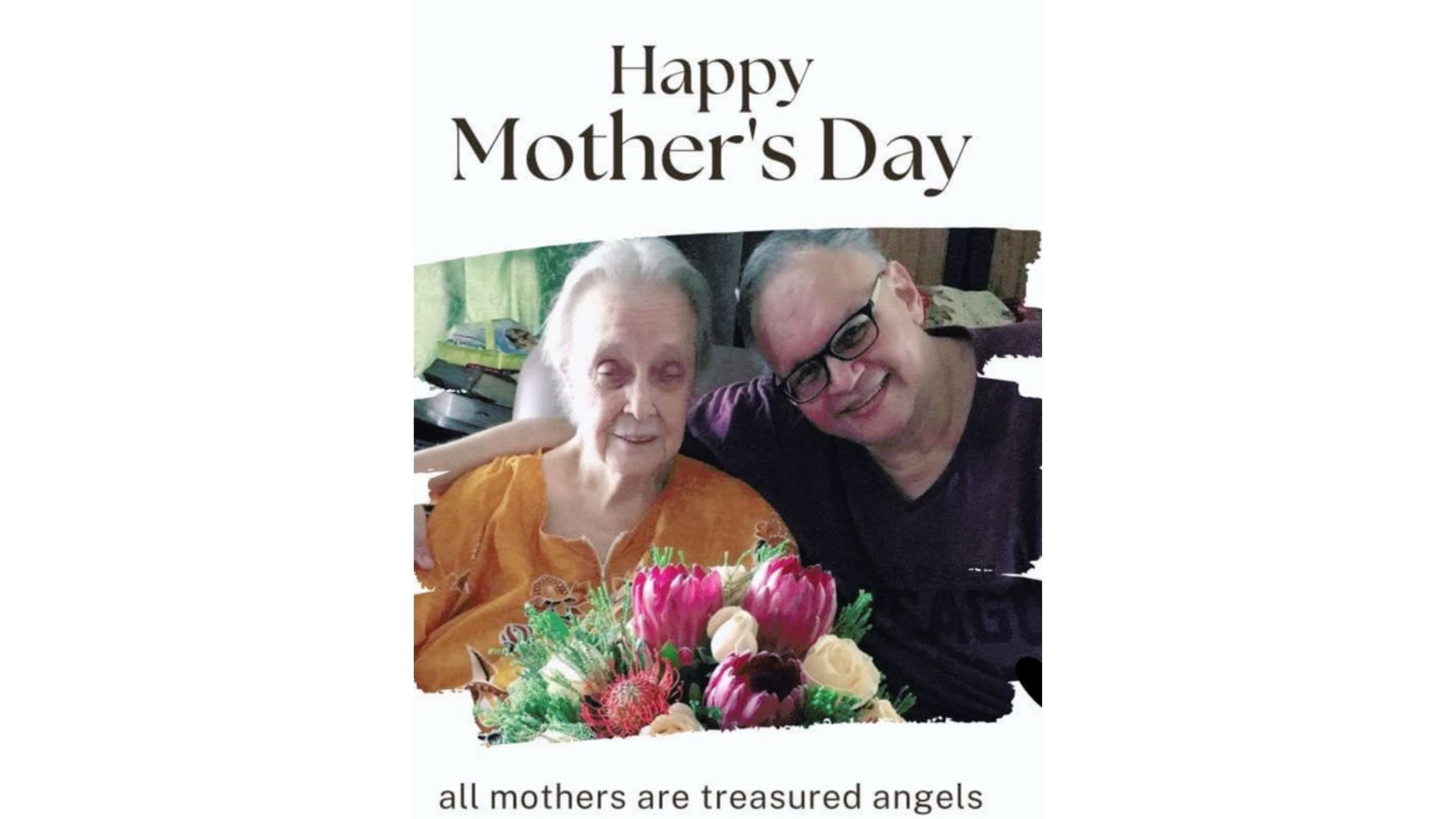

Then there is Mr Ian Poulier, 57, who is more an exception than the rule.

Mr Poulier was a counsellor and tutor after he graduated from university in the 1990s, but after his parents became seriously ill, he began working flexible hours to accommodate their needs for home care and regular visits to hospital.

After his father and elder brother died in the 2000s, he cut back on his work hours and worked more from home to care for his elderly mother, who is very frail and unable to care for herself unaided.

“After mum became bedridden from sustaining a fracture, my father, when he was still alive, and I hired a helper to look after her and especially to ensure that she took her medicine regularly. At first, I could do my counseling and tutoring work from home. But as mum’s condition deteriorated, I had to cut back on counselling, most of which had to be conducted by my partner. Eventually, I had to give up counselling altogether and rely more on tutoring to ensure that mum had adequate care,” he says.

High costs

The situation became more acute for Mr Poulier and his mother when the Covid-19 pandemic hit Singapore and the restrictions were in place. He was forced to rely more on tutoring and had to face higher medical costs and a rapidly depleting savings.

‘’Dad did not believe in getting medical insurance for the family, and it is hard to cope with the high medical costs for mum’s and my own medical conditions. The insurance would have helped offset a lot of the high costs of mum’s hospitalisations and treatments as well as equipment such as the hospital bed in our home. The Government has provided some financial assistance, but it has not been enough,’’ he says.

Mr Poulier’s mother, a retired primary school teacher in her late 80s, suffers from hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis, and had recently recovered from Covid-19 infection, despite being vaccinated. Mr Poulier himself has hypertension, diabetes, varicose veins, and eczema.

His own deteriorating health notwithstanding, Mr Poulier has to assume most of the responsibility of looking after his parents, and the presence of a full-time caregiver is not just a capable helpmate. Her absence would have had profound consequences on his health and well-being.

‘’I am thankful for my faith and the support from the church community as well as from the counselling community. But the long hours, the uncertainty of mum’s condition, and the medical emergencies, have taken a toll on my health, and this was particularly acute after the Covid-19 pandemic set in, especially during the Circuit Breaker period,’’ he says.

Caring facilities

The Ministry of Health (MOH) has expanded nursing home capacity in the last decade to meet the growing need for long-term residential care, yet also recognises the wide spectrum of needs for the seniors and that some may not be suited for nursing home care.

To support ageing in place, more than 4,500 daycare places and more than 3,100 home care places have been added since 2015.

The Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) estimates that the basic cost to stay in a nursing home, before subsidies, ranges from $2,000 to $3,600 a month. At the premium end, this might be in the range of $7,000 to $8,000.

And with government subsidies only available to households with per capita income of up to $2,800 a month, there might well be a sandwiched class that cannot afford an ideal level of nursing home care.

According to the findings of a 2018 study, Care Where You Are, by the Lien Foundation, home and centre-based care has overtaken nursing homes as the main form of long-term care in Singapore.

The capacity for home and centre-based care has doubled in recent years, and there are many sophisticated and newer models of care. But in Financial Year 2016, only a small fraction has been spent on home and centre-based care compared to the nursing home model – $240 million or less than 3 percent of the MOH budget of $9.8 billion.

On average, costs before subsidies for centre-based care, including the Integrated Home and Day Care Programme, range from $900 to $2,200 a month, while home-based care ranges from $23 an hour for personal care, to $95 to $150 a visit for medical, nursing and therapy care.

Families that do not qualify for the subsidies may end up hiring a foreign domestic worker instead, though they are usually not trained to manage people with complex care needs.

The study highlighted the fact that there seems to be care provision only at extremes — home-based or nursing-home based — with hardly any other options. This may create an artificially high demand for nursing homes, due to the lack of alternatives.

But there is a large group of seniors who are capable of fully independent living but do not have the high care needs, and assisted living can address the preference that Singaporeans have for ageing in their own homes.

This is seen in the fact that many seniors have moved from old homes to studio apartments, for instance, which allows them to realise the value of their initial property, says Professor Wee Shou Liang, of the Singapore Institute of Technology’s Health and Social Sciences faculty. Prof Wee is also research director of the MOH’s Geriatric Education and Research Institute (GERI).

Assisted living facilities, where residents are not reliant on caregivers, provide a “tailored level of support between that of community-based care support and nursing home care”, says Prof Wee. “More assisted living facilities may reduce demand for nursing homes, by delaying entry into a nursing home.”

The availability of more ageing alternatives is likely to be a significant help to the caregivers in the future. The predominance of women as caregivers for ageing parents puts a penalty on their own financial security.

The earlier they quit their careers or opt for more flexible working arrangements leads to greater financial penalties, especially in contributing to their CPF accounts, which helps build their retirement savings.

Freelancer Eugenia Chew has been fortunate to be able to weather the deepening crunch caring for her elderly mother puts on her savings and earnings. But if alternatives are not forthcoming soon, she may have to seriously consider a move that was previously considered out of the question — moving her mother to a nursing home or a similar facility.

“I promised my late father that I would do everything in my power to let Mum stay with me. But I could not predict the sudden and rapid effect of the Covid-19 pandemic or economic downturns then,” she says.

“I am glad that I can look after Mum for now, but later….I will have to cross that bridge when I come to it. It does not benefit me to think about it now. I will wait and see what further financial support there will be and then I hope to stave off the inevitable,’’ she says.

RELATED: The impact of caregiving on the economy: Dollar and sense of looking after seniors

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.