Playwright Haresh Sharma’s gateway into the realm of theatre began with acting roles for notable playwrights like Stella Kon and theatre companies such as the Third Stage. As an undergraduate, he joined Mr Alvin Tan’s The Necessary Stage, a fun theatre group which he started at the National University of Singapore (NUS). Inspired by the interest he received for his writing, Mr Haresh decided to write his first play in 1989 and it “just felt right”. From then on, there was no looking back.

To date, Mr Haresh has written over 100 plays that were staged locally and around the world. He was the 2015 recipient of the Cultural Medallion for excellence in theatre. His 1993 piece Off Centre, was about personal pride and had been restaged over the years to continued success. It is currently in the N & O Level syllabus as required reading.

“Off Centre is the gift that keeps on giving,” says Mr Haresh.

Past, present and future thespians

Reflecting on how the local arts scene was so new when he first started, he says back then, there was a sense of freedom in writing. With no predecessors to lean on, writers almost felt like they were inventing the wheel for theatre and playwriting in Singapore.

His early influences were the doyens of local theatre — the late Kuo Pao Kun, who wrote and directed Mandarin and English plays, and National University of Singapore (NUS) lecturer Arthur Yap. The focus in a space that was so new and raw was to go down to the bare necessities—good performances, good storytelling, he says.

Today, exposure to the arts is accessible from a young age. Future theatre aspirants have options that were not available in the 1980s. Children have the chance to enjoy theatre works through festivals, interactive theatre series and dedicated spaces at The Esplanade.

Lauding the theatre scene for realising the importance of representation, Mr Haresh hopes that the industry continues to encourage the plurality of different voices. To this end, he conducts workshops with people of different ages and demographics to bring about diverse voices in the realm of playwriting. Devising a workshop with non-binary people in 2020 for example, was “insightful and created a sense of community for the participants”.

“Spaces such as Brown Voices, Centre 42, the Inclusive Young Company (IYC) by the Singapore Repertory Theatre have done amazing work to include voices that were formerly lacking,” he says.

Working in the fringes has also allowed Mr Haresh to explore theatrical forms, issues and themes that may not be featured in mainstream works. This allows for a balance between new voices and the more experienced thespians.

Working with Equal Dreams, the official accessibility partner of the recent Fringe Festival has granted him insight into creating a more inclusive theatre experience.

“It’s not perfect but it’s better,” he says.

Our differences and sameness

Not wanting his lived experiences to cloud the reading of his plays, Mr Haresh does not feel the need to write plays about his personal identity markers.

“I want my plays to speak for themselves and not have my identity cloud the reading of the play. I want to write female characters as much as I want to write male and non-binary characters. I want to write straight characters as much as I want to write queer characters and Chinese, Malay characters as much as I want to write Indian characters. Their identities don’t just stop there, we can talk about it in terms of colour, class, and abilities,” Mr Haresh says.

“I want to write about things that I am not, learn more about our differences and sameness. We will all go through things that connect us. I feel that I am constantly learning and trying to make sense of it. That is important to me as a person and as a writer,” he adds.

Community building in tech

As a culture builder at tech company HubSpot, Mr Andee Chua’s role focuses on the company’s internal employees and workplace culture. The customer relationship management (CRM) company has over 5,000 employees globally, and 200 of them are in Singapore alone. Mr Chua’s role requires him to look at the employee experience from the time they are recruited, to their personal development within the company.

He also comes up with initiatives and programmes that focus on diversity, inclusion and belonging, to ensure that employees feel safe and are able to bring their best selves to work.

Outside of work, he is co-founder of Kampung Collective, which brings together community builders in the tech industry to share resources and learn from one another. He also volunteers for organisations such as She Loves Tech which supports women entrepreneurs and tech founders with personal branding and career development.

Pushing forward diversity and inclusion in the tech space

According to Mr Chua, the tech industry in Singapore is heavily influenced by the Silicon Valley of the United States (US), which invites a more inclusive and diverse culture compared to other industries here.

That being said, diversity and inclusion (D&I) has yet to become a priority for companies in Southeast Asia. The biggest push for D&I in the workplace has come from big US-based tech players such as Facebook, Google, and HubSpot.

“We’re slowly getting there, but you really only hear narratives about queers in tech during the Pride month of June,” he says.

What really matters are the companies’ policies that support queer folks employed there. “It boils down to day-to-day policies. Do queer folks feel safe coming out at work? Will their identity jeopardise their career? Are there policies that support the experiences that a queer person goes through in life, or do the policies only benefit cis and straight people?” he asks.

Cis refers to cisgender that describes a person whose gender identity is the same as their sex assigned at birth.

Mr Chua says HubSpot currently covers healthcare benefits for his long-term partner, although Singapore currently does not recognise gay marriages. Having queer visibility and representation at the management level is also important, says Mr Chua, so that people starting out in their careers know that there are opportunities for career development within the company, and their queer identity isn’t a barrier.

“At the same time, companies shouldn’t make you feel like being queer is your entire identity—you shouldn’t be put as the centre of attraction to talk about diversity, but you should feel included in the office everyday,” he adds.

Straddling the line between normalising queerness and increasing visibility

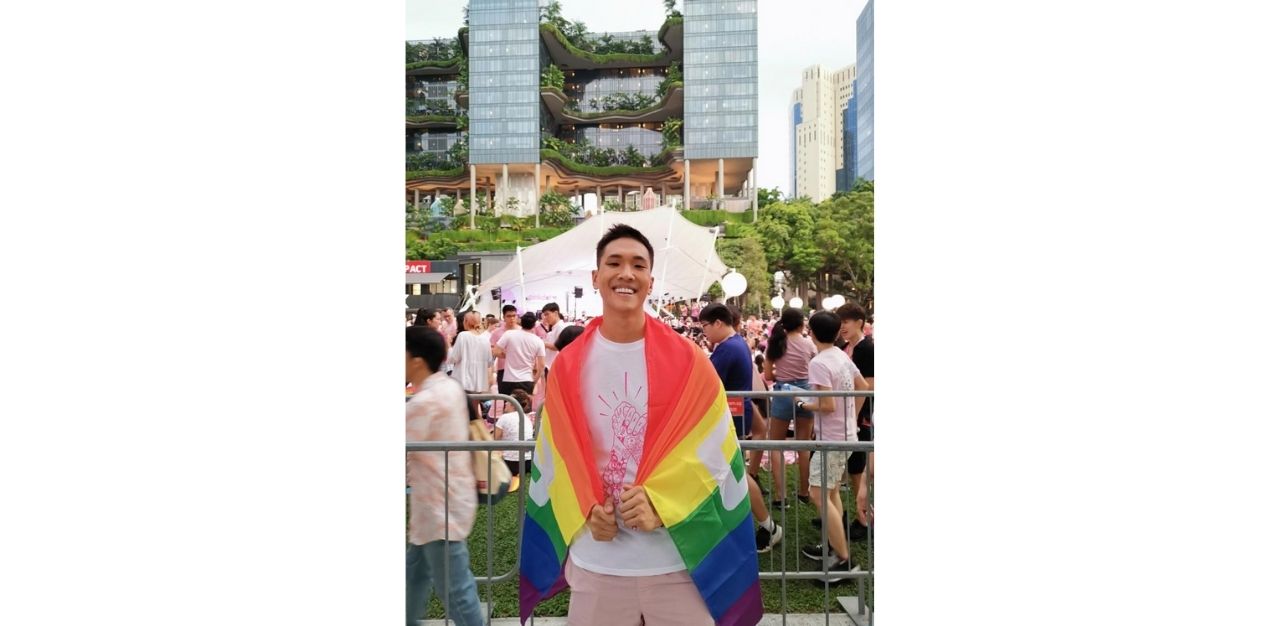

For Mr Chua, not every decision at work revolves around his identity as a queer person. “I want to normalise being queer. It shouldn’t be something special,” he says.

At the same time, coming out at work is still a “revolutionary step” for many, due to the fear and stigma that exists in Singapore and Asia at large. To this end, Mr Chua aims to continue being involved and be visible about his identity on social media to ensure that other queer folks feel safe approaching and sharing their experiences with him.

“As a gay person in Singapore, I think everyone’s very careful about who they speak to and how they present themselves. I’m privileged to finally be in a position where I feel comfortable sharing my voice and hopefully this moves the needle by just a bit,” he says.

Although he has been out about being gay for many years, he only chose to ‘come out’ on LinkedIn in 2020 as he found that there was not much discussion around queer topics on the platform. “There was a need for someone to speak up and I decided to. Since then, I’ve been able to not just talk about my queer identity, but have open discussions around queer-at-work topics with the community online.”

“I hope to see more companies in Southeast Asia think about how they’re walking the talk and actually supporting marginalised communities,” he says.

Healthcare through an intersectional lens

Resident doctor Jeremiah Pereira’s work revolves around advocating for the inequalities and barriers surrounding patients’ access to healthcare. For Dr Pereira, who goes by Mx Pereira and “they” instead of gender-specific pronouns, their queer identity has influenced how they view their medical practice as they’ve learnt to take an intersectional lens to the industry.

What this means is that in assessing patients, Mx Pereira takes into account how the patients’ various minority identities—gender, race, religion, class—intersect to determine their experiences and medical situations.

They say the dream is to eventually run a practice which is inclusive, where queer folks or different minorities are able to see a healthcare professional in a safe and non-judgemental space.

Although recent studies in the West have argued for the importance of queer-affirming healthcare and how it is more effective for individuals, it’s not yet practiced in Singapore, says Mx Pereira.

“These concepts aren’t even practiced in spaces where you would expect them to, such as endocrine clinics that provide hormones for individuals who are transitioning,” they say.

While there are organisations such as the T Project, and service providers such as the Gender Care Clinic at the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) that provide queer-affirming healthcare, those are few and far between.

“But I’m not just talking about queer-related healthcare services. Even General Practitioners (GP) should learn to provide safe spaces for queer individuals. It’s more likely that you’re going to see the doctor for things like taking blood pressure or checking for diabetes, but it can be quite intimidating to go to a clinic. This may dissuade a patient from getting the care that they deserve,” they say.

According to Mx Pereira, the crux of the problem is that currently there isn’t a medical syllabus that teaches doctors-to-be in Singapore how to provide queer-affirming healthcare. On the other hand, well-established institutions such as Harvard Medical School and Yale School of Medicine have included LGBTQ-specific health issues within their curricula.

Although most doctors in Singapore are well-intentioned, a dedicated syllabus is needed as there are specific terminologies, needs and experiences that doctors should be familiar with in order to create a safe space for queer individuals, Mx Pereira believes.

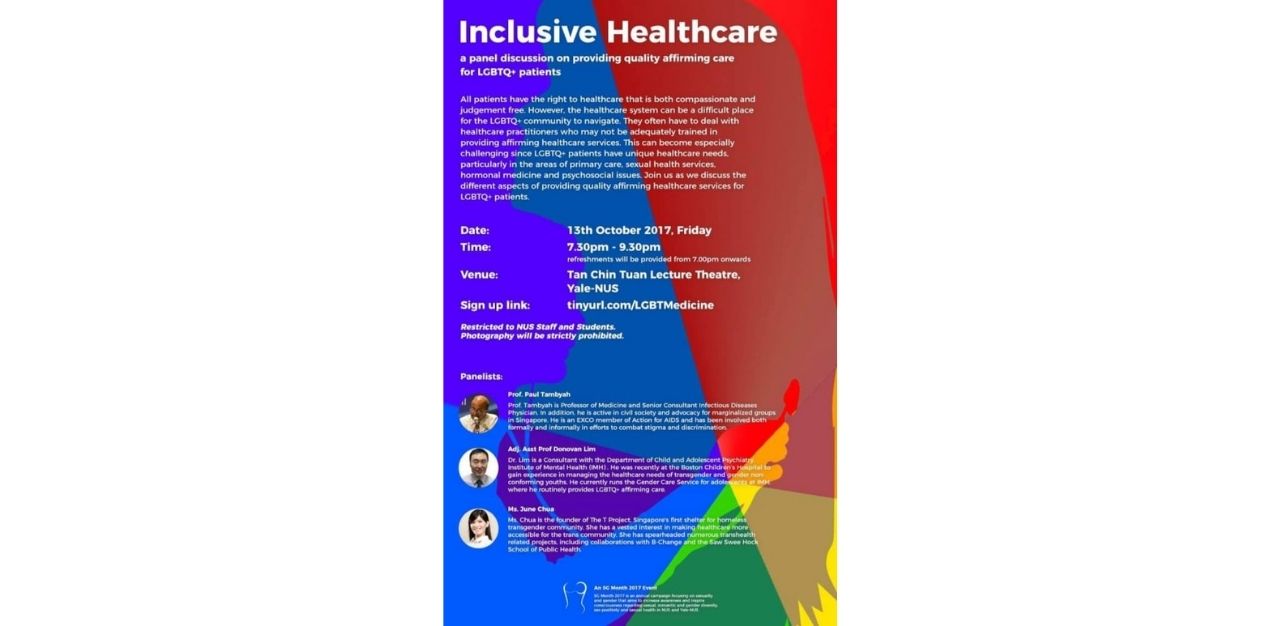

A role model that Mx Pereira looks up to is politician, doctor and professor of infectious diseases Paul Tambyah, who has been advocating for inclusive healthcare for many years. As a medical student in 2017, Mx Pereira organised a workshop about providing quality affirming care for LGBTQ+ patients, which Prof Tambyah kindly agreed to speak at.

Migrant workers left at the margins

One of the biggest ways that has changed how Mx Pereira practices medicine is that now, they always try to identify areas of discrimination that patients face—not just in gender and sexuality, but with race, poverty, and among the migrant workers.

At the height of the Covid-19 epidemic, when doctors were screening migrant workers to ensure that they were Covid-free, they witnessed a peak of diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol among the migrant workers who were seeing a doctor for the first time in years, Mx Pereira says.

“ The obstacle a migrant worker has when it comes to healthcare is probably a boss that doesn’t let him go to the clinic regularly, or feed him with nutritious meals. He’s probably eating a carb-based diet, which means that he’s at higher risks of other health problems,” they say.

“Now, doctors are more familiar with the problems faced by migrant workers, and have realised that these workers have been left by the wayside for the longest time,” they add.

Unfortunately, for many marginalised people, doctors only realised the problems at the end stage. “We tell Singaporeans that they should do a diabetes screening at 30 years old, and a colonoscopy at 40 years old or 10 years before the index case in your family. But for these people at the margins, they are not going for a colonoscopy if they cannot find an affirming healthcare provider. This will be the last thing on their list although we know that colorectal cancer is the number two cancer in Singapore and everyone should be getting a colonoscopy,” says Mx Pereira.

“Being queer has afforded me the opportunity to realise that we need to view patients through their intersecting minority identities, because that’s usually where the problems lie,” they add.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.