“Every farmer talks about the soil. And composting is a very essential biological component of soil regeneration,” says Darren Ho, urban farmer and founder of Petalicious.

Every time you harvest something and end up not using it, you throw it back into the soil for it to return to the cycle — that is the beauty of composting, according to Mr Ho.

In 2019, the Singaporean government announced the “30 by 30” strategy — to produce 30 percent of our nutritional needs locally and sustainably by 2030 — in a bid to lighten the nation’s overwhelming dependency on food imports. At present, the country brings in about 90 percent of its food supply from 170 countries, according to the Singapore Food Agency (SFA).

Given the drive toward growing our own food, what place does composting occupy in this lofty goal?

“When we throw away our food, the resources used to grow and deliver food to us are wasted. Additional resources will also be needed to collect, transport, and incinerate them,” said Dr Amy Khor, senior minister of state for the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment (MSE) during a virtual dialogue in April this year hosted by Eco-Business, “The truth about Singapore’s foodprint”.

That being so, it is imperative that we start viewing our food systems as cyclical, rather than linear. “It’s one thing to keep importing our food, but it’s not okay to just have nowhere to get rid of our food waste sustainably,” adds Mr Ho.

Yet, why are we not composting?

Oliver Truesdale Jutras, head chef at local farm-to-table restaurant, Open Farm Community, shares that where he comes from, composting is well and truly a part of the waste stream at each and every household.

“In Canada, we have a compost bin at home, and no food goes into the garbage at all. We separate our waste into four main streams: plastic, glass, paper, and compost. A separate truck comes by to pick up our compost,” he says.

It seems Singapore might be headed in a different direction altogether, for better or worse. “I think that the notion of composting is still very foreign to both public and private stakeholders. Right now, most are looking instead towards high-tech solutions,” says Mr Ho.

Here are the main reasons why.

1. It is the low and slow way

“Composting is really about inculcating biodiversity in our processes; you’ve got to feed [the soil] the right things to get the best things out of it,” says Mr Ho, who believes that for composting to be properly scalable, it requires “a complete shift in our thinking”.

“A big part of it is getting people to be more receptive to failure, because it is a very experimental process. It isn’t a short-term thing,” he says.

With no one-size-fits-all rule, the process requires one to be on the ball, dealing with different types of food waste day by day. Post-consumption waste or meat waste, for example, are significantly harder to manage and often take longer to break down.

2. It can get smelly

One hard truth is that composting tends to attract pests. The aerobic breakdown process results in warmer temperatures and odours, which may present a health hazard, especially for Food and Beverage (F&B) outlets.

“When we talked to the National Environmental Agency (NEA) about on-site composting at our restaurant about three to four years ago, they told us that it’s not allowed to be done close to F&B outlets, because it might attract rodents or other pests,” says Mr Truesdale-Jutras.

“We’re zoned as F&B on the map, so there are rules about trying to avoid pests, and having a heap of decomposing food waste is not really feasible,” he adds. “We have since occupied the agricultural land next door, but we have so much more land compared to regular F&B outlets.”

Tan Hang Chong, core team member at circular food community Foodscape Collective, highlights that composting requires time and space for trial-and-error.

“My mum complains about how I compost because she doesn’t like the smell,” he says. “People might think it’s hard or be averse to it, as when it becomes anaerobic (there’s not enough oxygen), the smell can get bad.”

3. It requires some experience and labour

Mr Truesdale-Jutras shares that with experienced management, there are ways to mitigate the undesirable side effects of compost.

“The easiest way to compost is to just throw stuff in a pile and let nature take its course, but that will attract more pests for sure,” he says. “A super well-managed compost pile with ashes and dry leaf litter probably wouldn’t smell.”

Adding about 25 kilograms of compost per week to their on-site compost system, he shares that just one trained gardener will be able to handle the manual labour of keeping up a healthy turnover for a compost pile.

The problem, however, might lie in finding that one trained person, partly because many Singaporeans are averse to “dirty” jobs. “Currently, there are not enough experienced gardeners or trainers in the composting community for it to be scalable, and those that exist are doing it at very small scales and are pretty fragmented,” adds Mr Ho.

4. It has yet to make financial sense

“Even though zero-waste businesses should technically be the most profitable businesses right now because all resources are maximised, many corporations in Singapore have no [financial] incentive to compost,” says Mr Tan.

Compared to other countries with volume charges for waste, not to mention mandatory waste segregation practices, Singapore charges a standard service fee for household and corporate waste collection.

This gives both households and food corporations little reason not to think twice about throwing out waste that can otherwise rejuvenate the soil.

At the same time, simply buying a bag of compost or soil from a nursery or supermarket would cost one about $5 — negating the effort and time of DIY-composting for many. “We have become victims of our own success,” adds Mr Tan.

Alternatives to composting

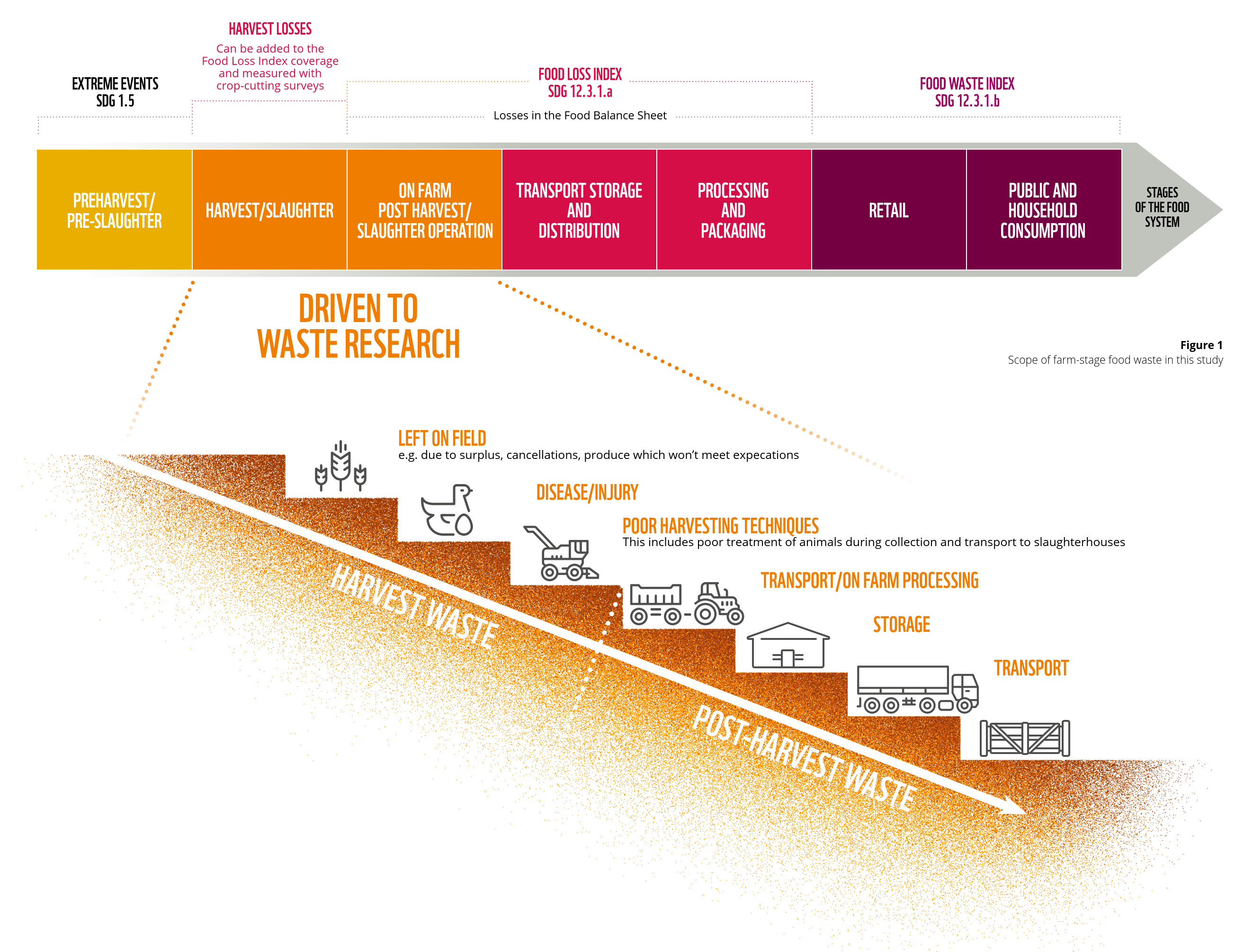

Mr Ho highlights that composting merely addresses one part of the waste streams in food supply chains. “It’s always the distribution and the pre-prepping the selection that carries the outcome, because those things are easier to control. After that, what’s done is pretty much done,” he says.

Many other food waste solutions hence exist to complement composting, but they each come with their pros and cons.

1. High-tech farming

As a counter-model to the “low and slow” way, the SFA is visibly banking on urban farming to ramp up local food production, having offered a total of $39.4 million to nine up-and-coming urban farms.

With a limited supply of arable land in Singapore to feed all on this sunny island, Mr Truesdale-Jutras sees the need for high-tech farms, which are often space and time efficient. But he believes that a blend of traditional and urban farming is ultimately more beneficial.

“I think that growing things in soil and being in tune with the land holds a very meaningful position in society, and I worry that high-tech farms might just remove us further from food chains,” he says.

He also points out that many high-tech farms do not operate cyclically, and import their seeds for each new crop cycle.

“It still makes for a good business, but food security wise, I don’t think there’s much of a difference between importing whole lettuce and importing seeds, because during times of crisis, seed suppliers are unlikely to continue sending over their seeds as well,” he adds.

2. Biodigesters

As opposed to composting systems, biodigesters are much less selective, making them much more scalable at this current juncture.

The Grand Hyatt Hotel, for example, has an on-site biodigester which addresses up to 500kg of food waste per day, and has saved $100,000 annually in the process.

“Biodigesters are a good short-term way to deal with most, if not all, sorts of food waste. They help to extract oil and salt from food sludge — which are very hard to break down naturally — and which can also be recycled for other purposes,” says Mr Ho.

It is important to note, however, that biodigestion is not composting, and much of biodigested waste ultimately ends up in our space-scarce landfill, Pulau Semakau.

“Food consists mainly of water, and that is not good for our incinerators for a heat-efficiency standpoint,” explains Mr Tan. So the main objective of biodigesters is to de-water our food waste, achieving 90 percent volume reduction for our landfills.”

3. Alternative composting

While still yet to be scalable, many new-age gardener-entrepreneurs are exploring other composting models.

Insectta, for example, is a local startup which employs black soldier flies to process food waste. The end products are high-value biomaterials that can be worth up to a few hundred dollars a gram.

“By harnessing these flies […], we have increased the value of food waste — where it once was a negative-value product — to a positive-value product,” Chua Kai-Ning, co-founder of Insectta, told the Straits Times.

Another alternative is Bokashi, an aerobic composting method originating from Korea and Japan.

“Personally, I think the products of Bokashi composting are a lot more versatile. Not only does it have a less pungent smell, you can sometimes even use the outputs directly as detergent or soap,” says Mr Ho.

Planting seeds of communal change

Mr Ho believes that Singapore is only still at the very beginning stages of this cultural shift — separating our waste and knowing what to compost.

A critical precursor to composting is first cultivating the habit of segregating waste, and Mr Ho believes that all stakeholders will have a role to play in normalising this habit.

“It’s hard for Singaporeans to change their practices unless the government eventually mandates that we have composting bins in our homes, hotels, and restaurants, so that all food scraps can be segregated,” he says.

This is well in the works. Dr Amy Khor announced in March 2019 that commercial and industrial premises that generate a large amount of food waste will be required to begin segregating food waste for treatment from 2024.

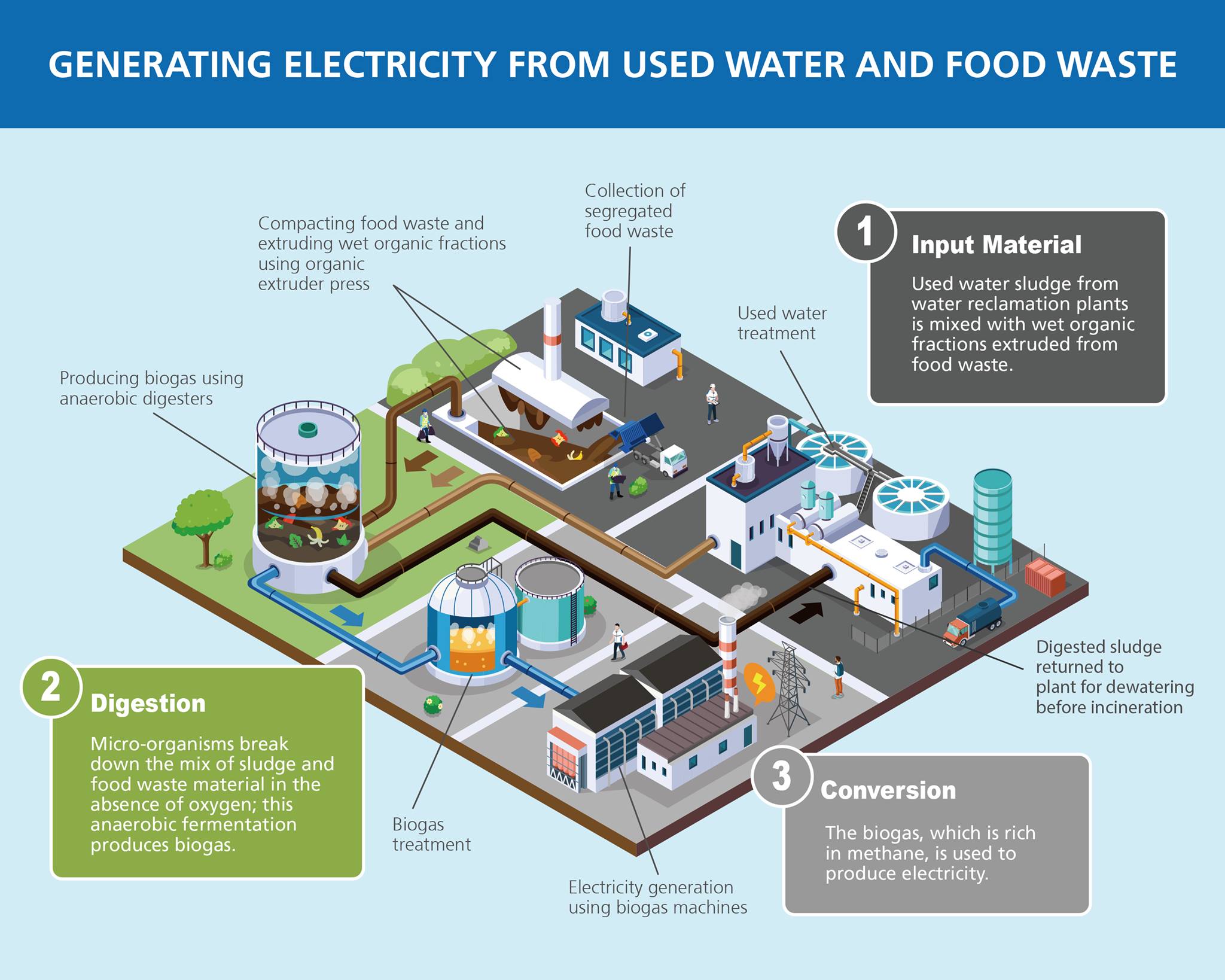

By 2028, an integrated water and solid waste treatment plan called the Tuas Nexus will also be constructed. The waste facility will convert methane-rich food waste into electricity, cutting a projected 200,000 tonnes of carbon emissions per year.

Pilot programmes have been tested out in residential communities such as the Tampines Greenlace HDB estate. The “Food Waste, Don’t Waste!” initiative had residents disposing of their food waste in dedicated food waste bins on the ground floor. The food waste was then recycled at Tampines Hub to produce fertiliser and non-potable water.

“It all begins with the people — perhaps those who have already bought into the idea,” says Mr Ho. “It could first start with Tampines Eco-Town, and then another, and then another… and soon, the whole of Singapore might be ready to compost a few years down the road.”

“Many in the government are also interested in looking into how to encourage more community composting facilities, and reaching out to us at Foodscape collective,” added Mr Tan. “We’re striking where the iron is hot and synergising with the growing demand for community gardens, especially since the Covid-19 lockdowns.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.