A landmark study conducted by Singapore’s Ministry of Social and Family Development and the National Council of Social Service found that children whose parents have been criminally convicted are about three times as likely to have been convicted themselves. While having the phenomenon confirmed in a local context is new, this theory has been published in other studies around the world, for instance in psychological studies conducted in the US (Pittsburgh Youth Study) and UK (Cambridge Study on Delinquent Development). This begs the questions: Why do the young offend and what can be done to prevent them from doing so? And do such studies perpetuate and reinforce stereotypes about who are predisposed to crime? TheHomeGround Asia seeks some answers.

One look at Yeo Yun Luo today will reveal no hints of his violent and tumultuous past. The man comes across as a natural leader, with his current position as a project lead in an engineering firm a testament to his capabilities. Yet, a look under the sleeves of his business attire will reveal sleeves of another kind – tattoos that hark back to Mr Yeo’s juvenile days.

With his affable and cheerful disposition, it is hard to believe that Mr Yeo had once used his leadership abilities in more nefarious ways – back when he was 16, his notoriety as a gang member was well-known in his neighbourhood and beyond. Quick to back up his fellow gang members in fights, Mr Yeo soon found himself on the wrong side of the law. Less than a year after joining the gang, he was charged with causing grievous hurt with a weapon.

Mr Yeo’s delinquent years trace back to a childhood fraught with challenges. It is a troubled past that may offer a glimpse into why he behaved the way he did.

Why the young offend

Mr Yeo’s parents had separated when he was 10 years old. Prior to that, they were constantly at odds with each other.

“They always fought,” he shares. “And the way they fought was very violent. Either one of them will get injured.”

After his folks separated, Mr Yeo lived with his father, a situation he was initially hesitant about as his father had “always hit him” when he was young.

“I [didn’t] have love from any of my parents,” says Mr Yeo, when speaking about his childhood.

A series of events and poor choices eventually resulted in him continually playing truant. One day, his father returned home early in the morning and found him sleeping at home.

“He was angry,” recalls Mr Yeo. “He told me in Hokkien, if you don’t want to go school, don’t waste my money. Then he said, ‘If you want to be bad, be bad all the way.’”

He continues, “I was thinking, you [his father] don’t care about me, every time I compete [in volleyball competitions], you don’t come and watch. I do good in school, you also don’t want to care. You want me to be bad? I will show you I can.”

And so, Mr Yeo started to mix with bad company, and everything followed on from there. Mr Yeo’s background does not excuse his behaviour but according to the sociological studies, it might explain some of it.

Saleemah Ismail, Co-founder and Executive Director of New Life Stories, is no stranger to such tales. New Life Stories is a non-profit on a mission to “prevent intergenerational incarceration” and recidivism, and to improve the quality of life for families of (ex-)offenders, with a focus on their children.

Ms Saleemah suggests that many youths who end up offending do so due to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), referring to traumatic events in a child’s life before they turn 18. These ACEs are categorised into three broad categories of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction.

“Many of us have been exposed to one or two ACEs,” expounds Ms Saleemah. “But for these cases that we work with, there’s a co-occurring of ACEs. The kids may be exposed to six to eight of these situations. The odds are stacked against them.”

ACEs and intergenerational crime

Having an incarcerated relative is one such ACE and a risk factor that can increase the likelihood of children offending in the future, although it is only one in a host of other contributing circumstances.

The 2020 study on intergenerational transmission of crime by the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) and National Council of Social Service (NCSS) suggests the presence of a “dose-response” relationship, where “an increase in parental criminal behaviour increases the likelihood of disruptions to family life, which can in turn affect child criminality.”

Soraya Abdul Rahim, a counsellor within the Family Care and Therapy department of New Life Stories, explains that there is usually trauma involved when parents are incarcerated.

“[This is so] especially if they witness the act of the person being arrested,” she says. “Sometimes, it’s hidden from the children, but all they know is that one day, their parent is here, and then the parent is gone. They’re not sure what happened…so there’s trauma, grief, loss issues, and a sense of abandonment.”

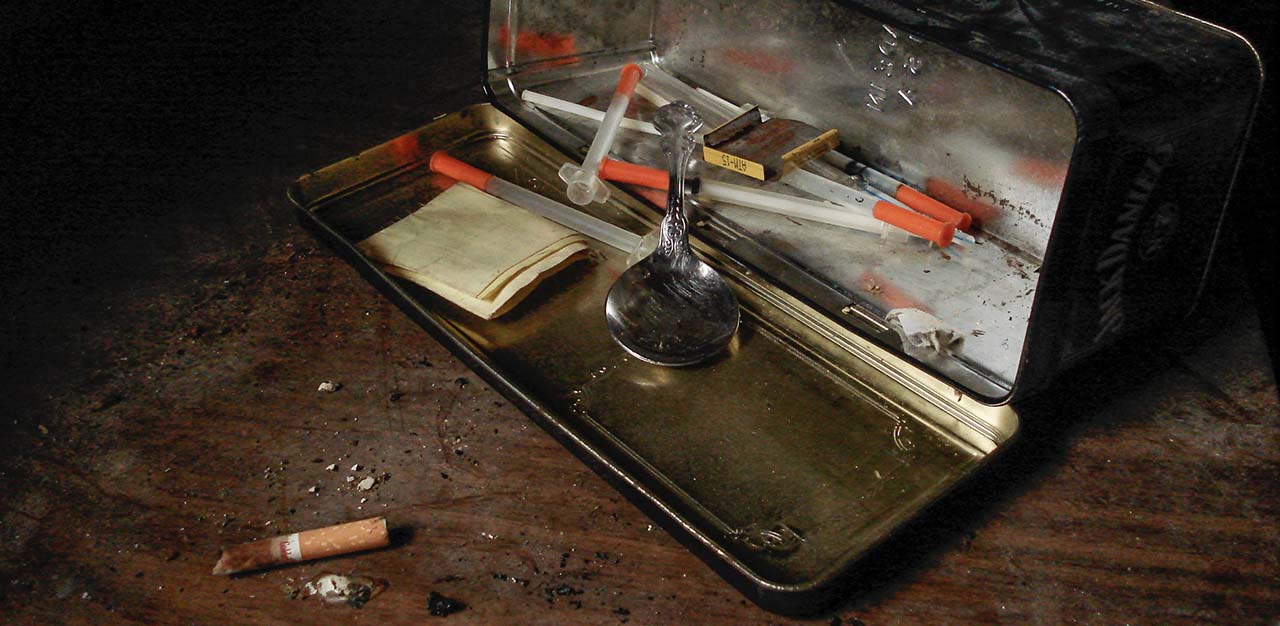

The study addresses drug offences in particular, and how children of parents who have committed drug offences are exceptionally vulnerable. It propounds that this could arise due to the addictive nature of drug use, which impedes the day-to-day functioning of a parent, affecting their ability to care for their family.

Ain Zainal, the Communications and Marketing Lead at New Life Stories relates an experience with one of their beneficiaries, who had started taking drugs after witnessing her relatives do so.

“Her mother and uncle were both taking drugs heavily at home and neglected her throughout her childhood,” shares Ms Ain. “She felt like she had no one to turn to, so she took drugs just so she could feel why her mother would prefer taking drugs as compared to spending time with her.”

Ms Saleemah chimes in, “You’re alone at home, your parents are doing something they consider more fun, so you will want to know why this thing is more important than me.”

But she is careful to note that intergenerational crime is usually a symptom of larger socio-economic problems: “It’s the poverty, kids being left alone, loneliness, sadness, it’s all of that.”

She offers another example of how children who engage in antisocial behaviour like bullying are often abused at home. For instance, one of New Life Stories’ beneficiaries has a mother on medication for severe anxiety and depression: “When she doesn’t have the drugs, she treats her kids so badly, she strips their dignity…She gets mad when one of her kids eats and drops his rice, she will ask him to eat like a dog, [putting] the rice on the table, [tying] his hands, and asking him to eat.”

According to Ms Saleemah, a child that is being mistreated will either withdraw or become a bully. Others turn to drugs to manage their pain: “That’s what happened for many of them, especially for the women who have been sexually abused. They take drugs as a form of self-medication to forget about it.”

Besides familial circumstances, external pressures such as stigma and discrimination can also add to the stressors faced by the children says Ms Saleemah: “There’s the stigma that just because their parents are in prison, therefore, there is something wrong with the kids.”

Adds Ms Ain, “People view them as rebellious, or that they don’t do well in school. But actually, given proper guidance and support, they can do well.”

She highlights that stigma and labels can become a self-fulfilling prophecy: “The children often have low self-esteem. They grow up in an environment where there’s a lot of cursing and swearing, and they’re told they are stupid. A child that has been told they are stupid, eventually believes it.”

And low self-esteem, research has shown, can predict criminal behaviour later in life, especially when conflated with an assortment of ACEs many children face.

Ms Saleemah explains, “Even if the parents didn’t go to prison, if they suffer from abuse, trauma, witness violence, they are going to suffer from emotional trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, all of these. If unresolved, it will be carried with them and affect how they make decisions, reduce their resilience at handling conflict, [and more]. All these add up.”

Crime is not ‘a disease’

Still, there are some who warn that the conclusions from studies about the intergenerational transmission of criminality can be misleading.

In a statement published on its website, a group in Singapore called the Transformative Justice Collective notes that the MSF-NCSS study frames the transmission of criminality in “dehumanising and essentialist ways”.

“‘Criminality’ is neither inherited like genes, nor ‘passed on’ like a disease,” it says. “Absent a nuanced examination of structural and systemic factors that place certain communities in conflict with the law, talking about intergenerational instances of offending can mislead the public into coming to troubling conclusions…This report suggests that being a child of someone who has been incarcerated predisposes one to lawbreaking.”

It argues that people who are affected by incarceration are often marginalised by class and ethnicity, while those who have been imprisoned, and by association their families, face “incredible stigma” from society.

“The trauma of losing a caregiver, and the social exclusion that children of incarcerated parents might face, can put them in positions that make them vulnerable to being in conflict with the law,” says the Transformative Justice Collective. “Rather than dispel the stigma around incarcerated people and their families, the MSF report intensifies it.”

Breaking the chain of criminality

Without intervention, children who experience multiple ACEs may end up dropping out of school or entering the juvenile justice system. For Mr Yeo, this situation rang true, although he has since turned his life around and reconciled with his family.

Ms Saleemah’s hope, though, is to intervene before children enter the system at all, and she tries to achieve this through New Life Stories.

The charity adopts a four-pronged approach: Befriending children through their Early Reader programme, counselling parents through the In-Care Mama and Papa programme, family therapy, and case management to assess the needs of the family.

Through these programmes, New Life Stories’ counsellors, case workers and volunteers hope to heal the relationship between parent and child, while working with caregivers to create a conducive environment for their growth. The reading programme, in particular, is unique to New Life Stories.

“The basis of [the programme] is the love from the child’s mother,” Ms Saleemah explains. “And that does wonders to a kid. It is an expression of love from their mother, and they have books written by their mothers.”

The programme has seen much success since its inception in 2014. Counsellor Ms Soraya reveals that many of the children have benefitted from it: “They are able to express themselves better. They have more confidence…There are also positive stories from teachers about the kids. Previously, they were considered troublemakers, and now, they do really well.”

Ultimately, New Life Stories’ programmes are an exercise in love.

“It’s about bridging communication between the parent and child even though they are separated by the prison walls,” says Ms Ain.

“We want to replace the kid’s sad memories and experiences with happy ones,” Ms Saleemah adds. “[We want their] overriding memory, the things that they go to bed with to not be, ‘I’m lonely. I’m sad. Nobody loves me.’ Rather, [we want them] to start their day with thoughts that they are loved, their parents love them.”

“Our words are creative,” she emphasises. “The words that we think about most actually become our reality. And that’s what we try to do with the kid. So that what they think and feel most eventually become their reality.”

Join the conversations on THG’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.