Growing up in Singapore, there was always a month in the year where respect to the dead was commissioned. The trail of incense and joss paper burning signaled the beginning; the flashy live performances (‘Ge Tai’) its peak.

The seventh month of the lunar calendar (July or August in the Western calendar) is known as ‘Ghost Month’ and the 15th day of the seventh month ‘Ghost Day’. A special custom to honour the spirits of the dead, it celebrates the Taoist (and Buddhist) belief in the afterlife. This year, the festival is held from 19 August to 16 September 2020, and as I’m writing, a familiar haze of smoke signals Ghost Day (2 September) is in full swing.

History

The festival’s origins come from a Buddhist tale of filial piety, where a Buddhist monk called Maudgalyayana (or Mulian) wanted to save his mother from perpetual hunger in the pits of hell. Buddha explained the only way was to make offerings to the monks returning from their annual retreat (15th day of the seventh month), as they could offer prayers that would bless his ancestors and relieve their suffering. As the story goes, Mulian’s mother was eventually raised from the status of hungry ghost to human being through this ritual, and thus, a new tradition was born.

Background

During Ghost Month, Chinese believe the Gates of Hell are opened, allowing spirits to roam the land of the living and visit their family members and descendants. These hungry ghouls are in constant search of food and entertainment, which is why all sorts of offerings are made — to keep the dead appeased and out of trouble.

While Taoists celebrate the festival as ‘Zhong Yuan Jie’ (or ‘中元节’), the Buddhists name it ‘Yu Lan Pen Jie’ (or ‘盂兰盆节’) — after the sutra from which the origin of this festival was derived. In Chinese tradition, deference and reverence to all ancestors is demanded; one of my earliest memories of Ghost Month was being instructed to say ‘excuse me’ whenever I passed offerings or prayer sticks, as an expression of respect.

Today, accidentally trampling on food, stepping on incense ashes, or kicking over joss sticks is still very much taboo, unless you’d like to suffer the wrath of angry spirits. The Chinese are a superstitious lot, but much of these special customs are centered around educating the next generation on proper decorum and the value of respecting the community’s elders and family members.

Offerings

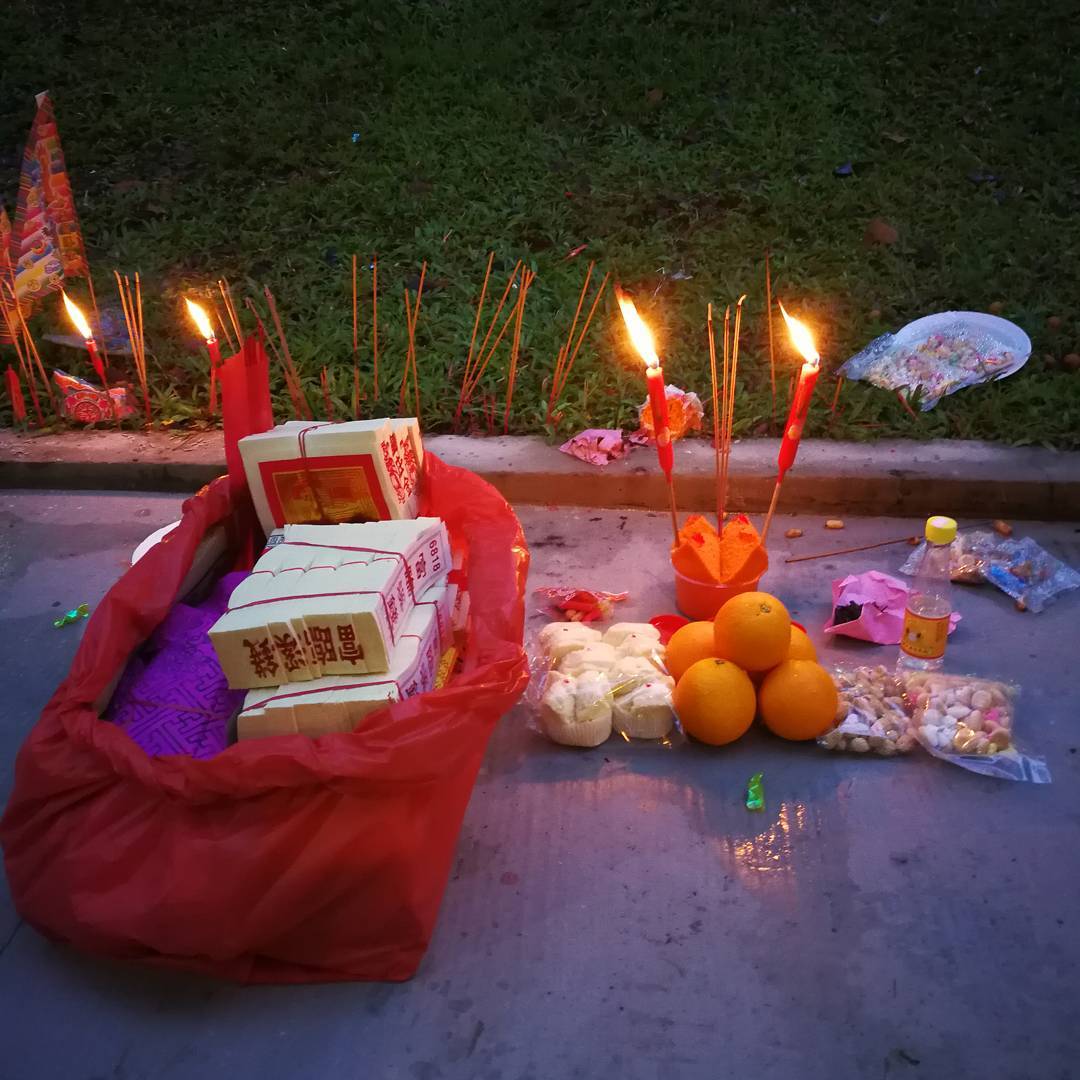

Following that line of thought, making offerings are a significant part of Ghost month tradition — families burn joss paper replicas of anything their ancestors might need in the afterlife. Paper money is the most common offering, but believers also burn paper cars, luxury houses, clothes, even paper durian and pets.

Much of the joss paper burning now takes place within dark-coloured metal bins scattered around heartland estates and at temples where large furnaces facilitate mass prayer. The tradition of offering joss sticks or plates of food (often unpeeled fruits, cake or a cup of tea) still holds, and you’ll see these along pathways and public housing void decks as an aid to prayer.

Ge Tai

Because wandering ghouls need entertainment, flashy performances and raucous auctions are also a mainstay. Unique to Singapore and Malaysia, these live performances are called ‘Ge Tai’ (literally translated to be song stage), and it’s often thrown by religious affiliations and temples as a culmination of Ghost Day. Large tents are temporarily set up in open fields, or in my case, an open car park and crowds of heartlanders and believers gather to watch.

Auctions are part of the lively affair, during which dinner attendees (usually members of the hosting association) bid for items ranging from a fan to thousand-dollar liquors. Winning the bid is as much about saving ‘face’ (prestige and social standing in the Chinese context) as an ego boost; things can get heated as bidders try to one-up each other.

As the night wears on, the live performances take over — singers in flamboyant, glittery costumes take center stage to perform songs in dialects — Hokkien, Cantonese, Teochew, Mandarin. The occasional Chinese opera performance and irreverent comedy dialogues intersperse the jazzed-up performances — it’s a heady mix of old and new that entertains with choreographed song numbers and technopop LED. Just be sure not to sit in the first row, as that is purely reserved for the ‘honoured guests’.