Towards the end of the 2019 Netflix documentary American Factory, the Chinese billionaire entrepreneur Cao Dewang reflected upon his life as he strolled pensively around what looked like a massive shrine dedicated to himself. Amid doubts that his glass empire had done more good than harm for society came one of many maxims that seem to undergird his civilisation: “The point of living is to work. Don’t you think so?”

The notion that a worthwhile life can only be attained through constant productive endeavours resonates with most people due in part to humankind’s inherent desire to be ‘of use’. Indeed, what Cao had meant was that the purpose of life is to be useful. The inclusion of the line in the documentary, an attempt to accentuate the contrast between the Chinese and American civilisations, had ended up — unbeknown, I suspect, to the directors — an apt commentary on workaholic cultures everywhere, including Singapore’s.

Working one of the longest workweeks in the developed world, Singaporeans have long been victims of workism. Any conversation about one’s work these days is doused with vaunted mentions of 12-hour work days, weekends taken up by work, and not having seen friends or had a hobby day in months. Adhering to the tenets of workism, there exists a belief among far too many Singaporeans that the hours one puts in is directly proportional to their productive output. As the author Mark Manson pointed out, most people believe work and productivity to have a linear relationship. But if we believed that, then East Asian countries such as South Korea and Japan would be some of the most productive places known to mankind. Lamentably, that is not how work actually works, and a look at Singapore’s productivity stats over the decades show that these long hours have not in fact translated to more productive output.

Are Singaporeans productive?

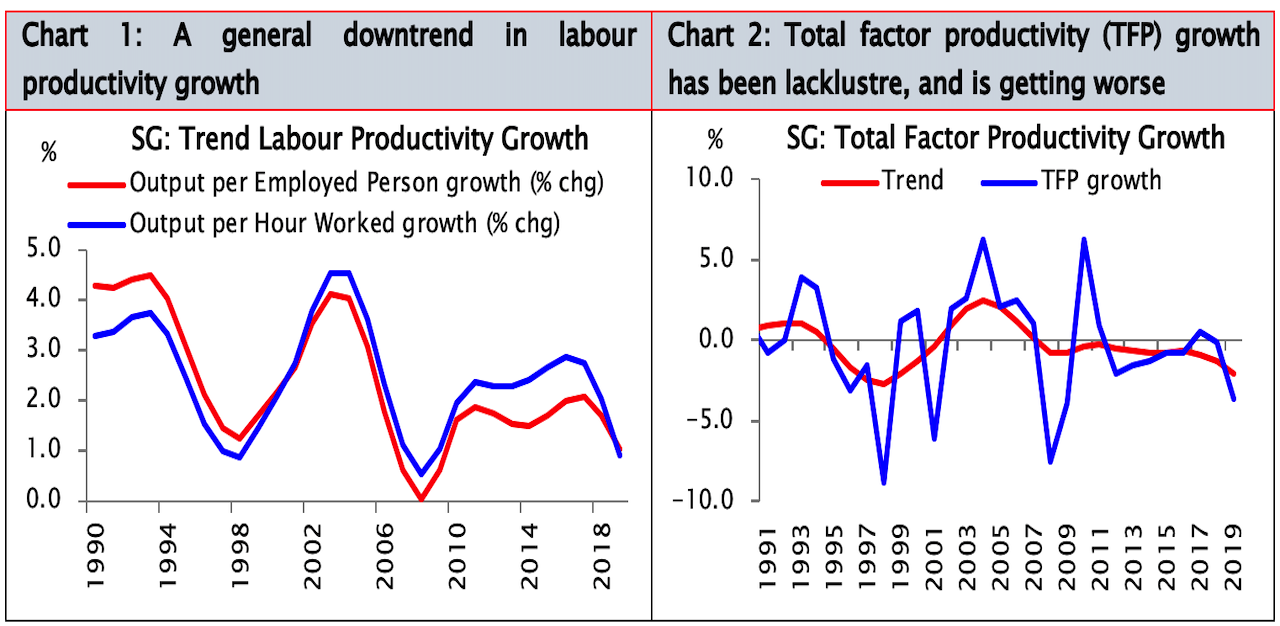

To make sense of Singapore’s unhealthy relationship with work, we first consider productivity and its components. In a recent analysis done by private sector economists Manu Bhaskaran and Nigel Chiang with data from the Department of Statistics and the Conference Board’s Total Economy Database, Singapore’s productivity performance over the past two decades has consistently lagged behind its high-income peers and the OECD average. Despite our gruellingly long hours — much longer than most of our peers in the OECD — labour productivity, which refers to the value a worker creates for every hour worked, is still lower than in most developed nations. Perhaps what is more striking is our negative total factor productivity (TFP), which Bhaskaran and Chiang’s analysis says is suggestive of an absence or under usage of hallmark advantages of an advanced economy, such as education, skills development and technology, in our industries and businesses.

Clearly, overworking has not resulted in increased productivity. In fact, it might have had the opposite effect. Over the past decade, some societies have ventured to ask themselves the all-important question on which the future of work might hinge — can we work less and still grow?

Having first taken off in Iceland, the idea of a four-day workweek or six-hour workday has since spread to nations like Spain and Finland as well as organisations across Japan, New Zealand and the United States, alluding to the increasingly apparent notion that sticking it out for eight to nine hours a day, five days a week might be one of the largest wastes of time for employees and organisations. After all, how much time in the office do we really spend on actual productive work, and how much of it is zoning out, chatting, cigarette and pantry breaks, unproductive meetings or Facebook? A study conducted by The Workforce Institute at UKG in 2018 discovered that close to half of employees surveyed worldwide believed they could complete their daily jobs in just five hours, while another study in the UK suggested that British employees’ “productive hours” only lasted a little under three hours in a given day.

The Icelandic trials conducted between 2015 and 2019 revealed that output can indeed be maintained even with shorter hours, which equates to an increase in productivity since the same amount of work is now being completed with less human labour hours. Closer to home, Microsoft Japan trialled a four-day workweek in 2019 — to the amazement of our mainstream media — and boosted labour productivity by 40 percent. These and other experiments have been hinting for a while now that working long hours might in fact be the antithesis of productivity, begging the question — why are Singaporeans still doing it?

The crux of the matter seems to lie in the work culture Singapore has cultivated over the decades, or what some might also refer to as our work ethic. Studies over the years have pointed to a tendency of Singaporeans’ to leave the workplace only after their bosses have, as a show of one’s work ethic and dedication. In other instances, this tendency turns into obligation as employees, from their interactions with bosses and understanding of the office culture, feel it is expected of them. Unsurprisingly, any incentive to be efficient and thus productive instantly evaporates. Why finish all my work earlier when I am stuck here until my boss leaves anyway?

Of course, the four-day workweek is no silver bullet to overworked societies in desperate need of the fabled work-life balance. If anything, the evidence available now suggests that the four-day workweek might not work for all employees nor just any organisation, and that success may have been partly due to complementary policies and initiatives. In the case of Microsoft Japan, its success with the four-day workweek had been due in part to its expressed support of employees’ use of the day off through expense subsidies.

In Singapore, progressive organisations have hopped on the bandwagon of flexible work hours in place of a rigid four-day mandate in efforts to empower their employees to live life on their terms, marking a promising shift in employers’ view of productivity and work.

Un-productivity and its deleterious nature

While productivity has been observed in these trials to improve with shorter hours spent at work, the cause of this improvement appears multifaceted. Apart from the obvious and unnecessary distractions that inhibit focus during a longer workday, studies like the Icelandic trials also uncover what more time away from work to be creative, build better relationships, and nurture complementary talents can ultimately do for productivity.

An employee perpetually in a time crunch because they lack the bandwidth to exercise, eat well, pursue hobbies, discover outlets for creative expression, develop relationships, be present for their family, attend to their mental health, and pursue self-actualisation can hardly be expected to be at their most productive, and expecting a workforce to produce their best work under such circumstances due to a fixation with an outdated view of a worthy life is quickly showing to be a fool’s errand.

Beyond economically-driven work, allowing employees to live fuller lives is also a way for employers to be socially responsible and acknowledge the value of other forms of work that exist outside of the economy, such as caring for the young and old in one’s family, fulfilling one’s spousal and filial duties, attaining mastery outside of one’s vocation, or participating in civil society to improve one’s community. Among these also lies the possibility of a more healthy fertility rate, as one study from the Institute for Family Studies (IFS) in the US had discovered.

A human-centric attitude to work

While work will always have its place in any society, when all is said and done, the goal of any prosperous nation lies in sustaining an exceptional quality of life for its citizens — working them to the bone goes against the very ideal.

A thriving society recognises that there is more to life than work — particularly unproductive work. This requires them to acknowledge that not all work is equal, and that a degree of intentionality will help guide us on this journey to live life on our terms. By focusing on employees’ needs and investing in systems and processes that incentivise less labour input and more focused, curated work, labour productivity will have space to improve as the need for long hours fades into obsolescence.

As we have gleaned from the various trials of the four-day workweek elsewhere, rethinking work and productivity is ultimately a whole-of-society mission, and the reward for it is gradually proving to be fuller, happier lives.

Chester Tan is a freelance writer, aspiring photojournalist, and communications student in his final year of university.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.