Does anyone know what to do when their HDB flat’s lease decay to zero?

That was what Mr Lee Hsien Yang, the younger son of modern Singapore’s founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, wrote on a Facebook post on 11 July.

In the post, Mr Lee said the past generation of homeowners had faith in the policies of the HDB and their leaders that their flats would provide a means for retirement.

“It was a matter of faith. Work hard, keep quiet, save for retirement and buy a HDB flat – getting on the housing ladder would lead to a better future and a comfortable, secure old age,” he said.

He also said that retirement and the current housing situation has become “a game of snakes and ladders, but with more snakes and fewer ladders”.

This resulted in a deluge of remarks and opinions on the internet as netizens revisited the issue by offering various sentiments on the topic. The public’s opinion on lease decay is nothing new.

In 2019, nonpartisan forum group Future of Singapore (FOSG), released a policy proposal addressing Singapore’s public housing problems such as asset protection, affordability, and access. Written by private economic consultant Yeoh Lam Keong, property consultant and author of real estate books Ku Swee Yong and veteran architect and founder of the group Tay Keng Soon, it even proposed a “one-time automatic top up” of all HDB flats owned by Singapore citizens back to 99 years once a HDB flat is 50 years-old.

The topic of lease decay was brought up again that same year when property site PropertyGuru posted a commentary by private investor and family office fund manager He Shen Chow, who said to the majority of Singaporeans, their home is their largest asset and nest egg, with more than 8 in 10 being HDB homes.

Mr He also said it is “profoundly confounding” that many Singaporean intellectuals have come to a collective view that an HDB residential asset with a 99-year lease is “a poison chalice because, at some stage in the future, its value will shrink to zero”.

A January article on the Life Finance Blog said the concern arises because “the rise in HDB flat prices over the years has outstripped the growth in wages by a long way” and the result of this is that “the average Singaporean has 50 per cent of his net worth on average tied up in the HDB flat”.

“For lower income Singaporeans, this can be as high as 90 per cent of their net worth. As many Singaporeans use their Central Provident Fund (CPF) savings to pay for their flats, much of their retirement savings are also locked up in the HDB flat. Hence, HDB lease decay implies a huge loss of these Singaporean’s savings and retirement funds as the lease runs down,” it said.

The Life Finance Blog, a blog which seeks to explore, educate and elucidate Singaporeans’ understanding of financial issues in living the life they want, also dealt with the issue of HDB lease decay in 2020.

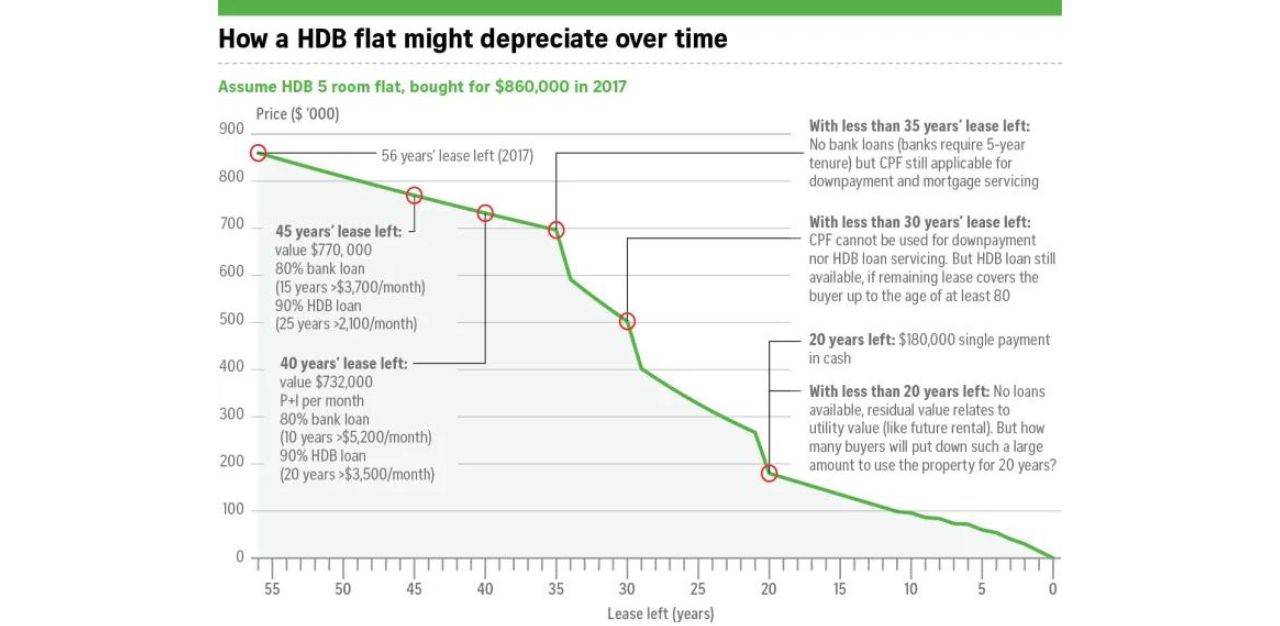

It projected that HDB flats on a 99-year leasehold may see their values start falling as early as the 45th year or when there are 54 years of the lease remaining.

The blog said using the chart of the market forecast of HDB lease decay as a guide, HDB lease decay has a “double whammy”.

It brought up the example of a couple, aged 40, having bought a 40-year old HDB flat for $860,000 in 2017 to raise a family and continue living there after they retire and the children have grown up and moved away. The site calculated that after 35 years, the HDB flat might only be worth $300,000, which meant that $560,000 has been lost through lease decay.

So, not only are Singaporeans putting a lot of their savings into their HDB flats, which cannot be easily monetised to pay for their expenses in retirement, but the savings put into the HDB flat also dwindles over time, leaving little for the next generation to inherit. These are hardly the characteristics of a good investment asset, it said.

While a response from the authorities has yet to come, it is clear that the topic is one that is top of everyone’s mind and could potentially become a wider political issue.

Are lease top-ups the answer to lease decay?

In Mr Lee Hsien Yang’s post, he cited that lease extensions similar to that of Hong Kong and the United Kingdom should be considered to make housing policy more ‘transparent’ and ‘equitable’.

Speaking to TheHomeGround Asia, Huttons Asia’s senior director of research Lee Sze Teck says a lease top-up is “workable and more sustainable”.

“A lease top-up gives people an assurance that they can continue to live in their flats beyond the lease. Buildings are built to last for years and by retaining it, greenhouse emission can be reduced. It is a matter of the mechanics like how many years to top up, how much is the top up, how to pay for and who qualifies for the top up,” says Mr Lee.

He points out that such top-ups would require further regulations to deal with potential complications.

“However it may give rise to a situation where owners try to put a premium on their flats when they sell as the buyers have an option to top up the lease. Controls can be put in place like the right to top up resides with the current owner and is not transferable on sale, that is, one top up per flat, an MOP period when owners top up their lease,” adds Mr Lee.

He points out that the next batch of flats approaching the 70-year old mark are the terrace houses at Jalan Bahagia and Queenstown and says that the possibility of lease top-ups is “remote” as the units are low-rise housing, and that are “likely to be offered another housing option once the lease expires”.

Mr Lee also suggests adaptive reuse of older flats where “silver housing townships, co-living, or rental can be explored”.

ERA Realty’s head of research and consultancy Nicholas Mak, agreed that lease top-ups are feasible but questioned the rationale behind it.

“Why would anyone in the HDB want to do that? Most people buy a flat between the ages of 30 and 40 years-old. In 40 years, they’ll be retirees who need money for retirement. Why would you ask them to put their most liquid asset, cash, into a non-liquid asset, brick and mortar? Even if a person buys an HDB flat at the age of 51, very few people are going to live to be 120 years old. A lease top-up is feasible, but it doesn’t make sense,” he says.

Mr Mak also notes how Singapore’s ageing population is a consideration and urged for more patience with the authorities.

“As our HDB flats age, so does the population. We have an ageing population where the average household is getting older. Do we want a retired couple who are living off their savings or passive income to top up their lease? No. So if a flat has enough remaining years to see this couple till the age of 95, that is good as they will not outlive the lease of the flat. The important thing is for them to have a roof over their head and enough money to see through the rest of their days. Depreciation is not the problem. Have we forgotten that we are ‘consuming’ the lease of the flat? If the lease runs down, it’s supposed to because it’s finite,” he says.

“In Hong Kong when you buy public housing, profits made from selling are taxed. The government has been fairly generous in SERS by offering replacement plans in a nearby locality and the various scheme benefits. The whole idea of leaseholds is so that the land can be redeveloped for future generations. To tackle worries about lease decay, the government will refine policies like SERS and VERS. We should wait for the news to come out.”

Have the narratives and perspectives around HDB decaying leases changed?

In a 2017 blog post, Minister Lawrence Wong cautioned Singaporeans that not all old HDB flats will be automatically eligible for the SERS, and noted that only 4 per cent of HDB flats have been identified for SERS since the scheme’s launch in 1995.

Mr Wong was responding to a Lianhe Zaobao report in the same year which highlighted the high prices of several short-lease HDB flats in the resale market.

This caused the worry of lease decay to resurface when the clear stand on SERS was that it is not a ‘jackpot’ of everyone. The undersupply of new BTOs, coupled with long waiting times exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, pushed potential homeowners towards the resale market to secure a home, and reframed the housing needs of Singaporeans.

Also, after the recent June SERS project in Ang Mo Kio, homeowners were left worried as they expressed affordability concerns for the replacement flats provided. To this, the authorities responded by offering residents there a new 50-year lease option.

Although it was noted that the Ang Mo Kio SERS project was different as the age of leases was older than in prior SERS projects, it caused much debate online and the perception of HDB leases to shift.

Mr Mak notes how Singapore’s view on HDB’s as lucrative investments might affect their perception of lease decays.

“A HDB flat should be a home more than an investment and I can understand why. If someone buys a property and they hear of people making money from property, they will want a slice of the share. And this becomes a catch-22 situation because when prices of resale flats go up, current owners will be happy as their flats are worth more in value, whereas those who haven’t owned property will lose out,” he says.

“I think the government has said enough. It’s hard to change what people think. If a government can change the way people think we’re talking about an Orwellian 1984 situation. People will think what they want to think,” he adds.

Former Minister of National Development Mah Bow Tan, who held the office between 1999 and 2011, had likened HDB flats to assets then.

In a collection of commentaries published in 2011, titled Reflections of Housing a Nation, Mr Mah said: “Once they own the flat, it’s an asset. And this asset can be cashed out in old age, be used to finance their retirement. It’s a store of value for them … the home ownership policy is the key pillar of our public housing system. We want Singaporeans to be able to own both a home and an asset that is a hedge against inflation and which appreciates with the country’s growth.”

Veteran journalist Bertha Henson also weighed in on the issue. She labelled the HDB as a ‘many-headed Hydra’ in her Facebook post, citing HDB’s ambiguity in their messages to the public.

She wrote: “It (HDB) can’t speak from both sides of the mouth, talking about asset appreciation and warning about lease decay. Time it clarifies its role – as provider/seller of public housing as housing/investment, and how it will deal with ageing flats.”

A decaying house of cards?

As the nation’s stock of flats age, it remains to be seen exactly how authorities will deal with the decaying leases and the differing views of the public. What is clear is that it remains a concern for many Singaporeans.

Ms Henson felt that regardless of previous developments, the topic of decaying leases has become a “political issue”.

Rounding off his post, Mr Lee Hsien Yang said that it is urgent for the authorities to provide the public with solutions to the question that has been giving Singaporeans anxiety over their future.

“It should not be an inevitable countdown to zero destroying the promised dream of a settled future for which Singaporeans have paid and kept paying all their lives, paid GST, paid into CPF, paid with obedience and acquiescence, and paid with votes in 2020. Singaporeans, are you better off today than you were two years ago?” he asked.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.