Dungeons and Dragons is a roleplaying game that is making a comeback in Singapore – and now you can pay to play by hiring professional Dungeon Masters to run the game for you. What is it like to make a living out of bringing fantasy worlds to life? And what can storytelling games add to a table bristling with entertainment options?

We sit, shimmering with sweat, in the afternoon heat of Singapore: Five friends occasionally brushing our feet against the dogs that nap underneath the table.

Yet, we are also crouched together under a starry sky, huddled in the doorway of a pie shop in a sleepy village named Womford, hatching plans to steal pies.

We are, in other words, playing Dungeons and Dragons (D&D).

“Is the door locked?” I ask. My character is Lottie, a halfling travelling the world to catalogue the world’s finest delicacies (by eating them), and she is desperate to try these pies.

“You gingerly reach out and try the handle,” our Dungeon Master (DM) – the game master who describes the world we live in – replies. “It gives easily under your touch.”

“Lottie bursts in the door!” I exclaim dramatically.

“Shiv follows right after,” my friend responds. Her character, Shiv, is a half-elf who conceals a tenderhearted interior under a gruff persona.

“Lottie yells ‘look! That way!’ in an attempt to distract the piemakers!” I wave my hands in the air approximating Lottie’s actions.

“Roll a performance check,” the DM says.

A die clatters across the table, skipping over scraps of paper and potato crisp crumbs, and we all look at it and groan: “I rolled a three.”

The DM breaks the bad news: “Your attempt at distracting the pie makers has failed,” and elaborates, “A young man with a flour-stained apron, holding a tray of freshly baked pies, looks at you and raises an eyebrow.” He adopts an exasperated tone: “‘Who are you? What are you talking about?’”

In desperation, my friend attempts to salvage the situation: “Shiv reaches out and slaps the pie tray out of his hands!”.

We all howl with laughter. We are teachers, actors, government officers. But we are also Shiv and Lottie, ineptly engaging in a pie burglary.

Wizard behind the curtain, enter the Dungeon Master

If you could be someone else for a day, who would you choose to be?

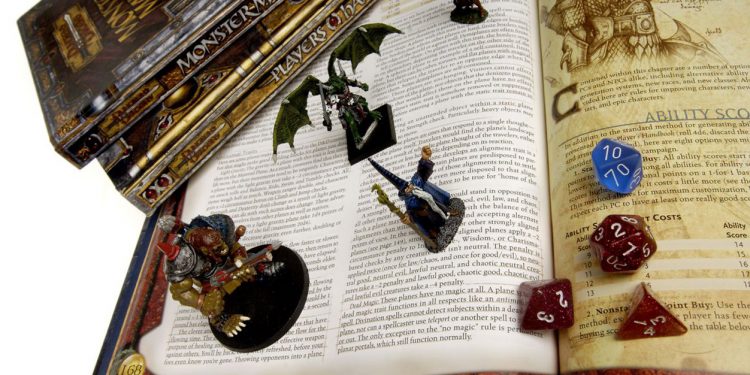

That is the hook offered by D&D – a tabletop role-playing game (TTRPG); where you can play an elf searching for his long-lost parents, a dwarf finding ways to restore her kingdom to glory, or a halfling who wants to taste everything the world has to offer.

Unlike video games or board games, D&D is a collaborative storytelling experience. You say what you do, and your group rejoins accordingly. You can interact with shopkeepers or fight goblins to rescue prisoners. Often, you roll dice to see whether you succeed or fail.

Crucial to this make-believe universe is the DM, who describes the world and tells you the consequences of your actions.

Without a DM, there is no game.

They have to write or study settings so they can help players envision the world they are in; they run battles, keeping careful track of hit points and combat effects; and they inhabit every character the players interact with, from a weary tavern keeper to a condescending enemy dragon.

While being a DM is something that friends in the D&D scene do for each other as a hobby, in Singapore, there is a growing number of people who work as professional DMs.

You can pay someone to make a story come to life for you and your friends, and in Singapore’s maturing TTRPG scene, you have a range of options.

Rolling with it as a DM

A lot of D&D players shy away from undertaking the DM role because it takes so much preparation to run a game. Not only do DMs have to be technically versed in the game’s rules, they also have to be ready to react to whatever actions players take.

“In D&D, the best DMs can say ‘yes’ to anything that is logical within the world,” says Melvyn Sin. “As a DM, you keep throwing questions to your party until you find the hook that gets them. And then that’s the thread that you pull on.”

Mr Sin is a day trader who works as a part-time DM. To find new clients, he relies on word-of-mouth and his listing on Carousell as a Dungeon Master for hire.

He charges S$75 (US$56) for a session consisting of three to five players that lasts between four and six hours.

“I love navigating unexpected player choices,” Mr Sin says.

He describes a game where the party transformed a simple fight in a pub into a faction dispute in a bath house, which forced him to rapidly switch up his planned opponents and battleground.

“You want to reward that creativity. You just have to say ‘yes’ to it,” he says. “It unfolded in the most beautiful way. The consequences of that kind of creative problem-solving approach is more great story.”

As part of his craft, Mr Sin started taking improv classes three years ago to sharpen his skills as a dungeon master, and now finds himself regularly writing sketches and practising improv.

And it is not the money that draws him to the role. “The experience of finding a group of strangers and getting an emotional reaction is magical. It’s different from performing on stage, where the energy of an audience is loud. But here the energy is intimate and personal,” he explains.

“When players talk about what happens, it’s like they’re talking about a real thing that happened in their lives. It’s innately powerful, and I’m honoured to be an avatar.”

While part-time DMs like Mr Sin work on a freelance basis, there are also TTRPG studios in Singapore that devote physical spaces to hosting D&D, and other tabletop games.

Places like Tinker Tales Studios and TableMinis hire a team of DMs – some of them full-time – and organise games on a regular basis. Instead of them coming to you, you go to them for a unique player experience.

Curating player experiences

“There is this mentality that DMing cannot be a full-time job,” Nicholas Chan says. “At most it can only be a side hustle.”

Mr Chan is a professional DM working with TTRPG space Tinker Tales Studios – a cosy space in Bukit Merah heaped with miniatures, maps and D&D playbooks.

For S$20, studio visitors can spend several hours immersed in a different world, guided by an experienced DM and plied with a free flow of snacks and drinks.

Mello H., the owner of Tinker Tales, says that one of the reasons she set up a studio was to create an experience different from game shops – where public games of D&D are conventionally played in Singapore.

At game shops, D&D is usually played at multiple tables at once, and players often focus on combat (in-game fights against enemies) and levelling up their characters (gaining new abilities as characters grow in experience), rather than roleplaying.

“The booking system at game shops means that it’s fastest fingers first to secure a spot at a table,” Ms Mello explains, “and sometimes you might play with people you’re not comfortable with.”

Studios, on the other hand, can offer a more personalised experience, putting together groups by matching players and DMs based on what play styles they prefer.

Dennet Krishnan and Farez Najid, professional DMs working at TTRPG studio TableMinis, operate on a similar philosophy of “finding your table.”

Located at Wintech Centre, TableMinis is a sleek new space that often hosts workshops aimed at teaching newbies how to play D&D. Their prices start at S$25 for a beginner workshop.

“Finding the group that you can gel with is very important,” Mr Dennet says. “Some people like combat and others like stories… The ‘problem player’ isn’t a problem, he just hasn’t found the right table yet.”

Creating safe spaces for storytelling

Responsibly managing the boundaries of storytelling in a game like D&D, where almost anything goes, is also a cornerstone of being a good DM.

Tinker Tales uses consent checklists and traffic light systems to help players indicate when they are uncomfortable with the themes – which can range from degrees of romance to descriptions of creatures that might induce phobias, such as spiders – emerging in the storytelling.

“This way, we can stop play if topics are getting too heavy,” Ms Mello says. “It boils down to trust. People have to trust the DM and the studio.”

The intimacy of a studio also nurtures the privacy that players need to explore more controversial themes together.

“On many occasions, there was a bunch of adults at the table looking for a more complete experience,” Mr Chan shares about his experience as a DM.

“If you’re running a game where players are interested in exploring mature themes, like body horror, it’s not conducive to do this in game shops where passers-by or people listening in can judge you,” he explains. “People don’t know that all of you have consented to these themes and are building the story together.”

Consent, however, is something that is constantly negotiated.

Players’ preferences may change as they grow more familiar with each other and the DM; they might find that they are willing to try something they were initially worried about, such as roleplaying a romantic relationship. Or they might realise that they are uncomfortable with something they thought they had no issue with initially, such as descriptions of violence.

As the story shifts and grows, it is up to the DM to check in with players, and to co-create new boundaries and new possibilities.

Messrs Dennet and Farez are also committed to creating inclusive spaces for players so that they can feel secure enough to be open, honest and vulnerable with their storytelling.

“I have two non-binary characters in my games, who identify as ‘they/them’,” Mr Dennet says. “Remembering the right pronouns takes practice. This whole thing is new to me but part of the point of D&D is to experience life from a different perspective.”

But true inclusiveness remains an aspiration, rather than a reality for now, acknowledges Mr Farez. Part of good DMing, he notes, is recognising the limitations of one’s lived experiences.

“The lines change almost every day, and there are intersections to these lines,” Mr Farez says. “As individuals, we are not privy to every demographic. As a DM I must acknowledge what I do not know, what I do not understand.”

Crunching numbers in the economy of DMing

To be a DM, you have to possess a range of skills: A cool head for numbers and rules, the ability to deal with surprises, an understanding of the shape of stories, a sensitivity to the vulnerability that comes when people tell stories together, and the right people skills to manage player dynamics and emotions.

Running a game takes a few hours but preparing for it can take the same amount of time and more. Add to this the costs of buying dice, making miniatures to represent characters, and creating maps for battles. On top of that is the long-term work that DMs put into developing their abilities, such as taking improv classes.

Studios also have to cover rental, logistics and scheduling, player coordination, preparing new table-top systems, and setting aside time for their DMs to write new creative material.

If you think about it as an entertainment experience, a game of D&D at a TTRPG studio costs as much as watching a movie (plus popcorn) in the theatres – only you are the star.

Ms Mello and Mr Chan once overheard players comparing the ticket price of a game to the cost of a dance class at a studio.

Or, as Mr Dennet suggests, think of it as paying for an escape room experience or a game of street soccer.

“For players like me who are really hardcore,” Mr Dennet says, “I’m willing to spend up to S$400 to S$500 a month for a good DM to run a number of games for me. I think of it like hiring a personal trainer.”

Mr Chan muses that the role of a Dungeon Master is akin to being a tennis coach or a speech and drama teacher.

“It’s always a freelance gig at first until you have enough clients,” he says. “Ultimately, it’s a passion-fuelled job. In our Asian culture, there’s an emphasis placed on job security and safety nets. But there are always people willing to take the risk.”

Still, with enough time, Mr Dennet thinks that it is possible to build a career as a full-time DM. “If you run a certain number of games per month, you can earn four to five grand – more than some tuition teachers,” he states. “But you have to think creatively. For example, if you have a coaching background, like I do, you can make a D&D curriculum for organisations.”

Schools, for instance, are beginning to recognise that D&D is a game that teaches collaboration, turn-taking, and self-expression, and want to incorporate D&D into their curriculum. This has translated into a growing demand for DMs who can teach students how to play.

“Thirty-minute games of fighting orcs and finding treasure. They loved it,” says Mr Farez, whose specialty is working with children. He organises role-playing games with youth through the Tak Takut Kids Club, run by non-profit 3Pumpkins.

“When we stopped our games due to Covid-19, the kids made artwork of their own stories,” he shares. “And the effect is so tangible. We saw children unable to interact with others speaking so much better now.”

‘It’s a practice for life’

Ultimately, DMs and studios agree that the TTRPG market is growing steadily. Instead of seeing themselves as competitors jostling for space in a niche market, their interest is in growing the player base so that DMs have their pick of games to run.

Part of Messrs Farez and Dennet’s plan to attract more players and draw the existing community together was to launch a podcast called Alamak! You D&D?!.

As Ms Mello puts it: Why compete for a slice of a small pie when you can work on making that pie bigger?

The magic of sharing a story – of building a story together – is profound.

Dungeon Masters, of course, believe in the power of the game.

“D&D is like working in an ensemble. No one is leading or following. One of the improv rules we learn is ‘yes, and’,” sums up Mr Farez. “D&D allows you a safe space to say ‘yes, and’, and not feel the repercussions of your decisions and actions… I would say D&D is a practice for life.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.