A month-long fever and a constant “splitting” headache were what tipped Calvin Tan off to the fact that something was amiss with himself in March 2015.

“It was at this point of time [that] I realised something [was] up and I wanted to get tested for it,” he says. But he lacked the energy to go out and get tested then, being bedridden at the time. He subsequently visited the Accident & Emergency Department (A&E) with his mother when his fever had abated.

“The nurse said whatever was there was gone. Because my fever just disappeared,” he recalls.

Eventually, he decided to take a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test at the Anonymous Testing Service offered by Action for AIDS (AfA).

It was positive.

“It [was] a huge wake-up call. Like, ‘Oh, shit, this is happening, because of something that I did’,” Mr Tan says.

Individuals who receive a reactive test result have to send a blood sample to a lab for a confirmation test, the results of which would be returned in approximately two weeks, he adds. Being a polytechnic student then, the two week interval was during the school holidays. Mr Tan chose to hole himself up at home.

“I was given one of the [AfA] staff’s [phone] number. They said if I needed someone to talk to, they’ll be there. But I didn’t call at all… It [was] a very, very dark time,” he says.

Doubts about the future plagued his thoughts.

“I was feeling a lot of stress and pressure thinking of what to do next. Now that I’m probably going to be confirmed positive, what’s the next thing to do? Do I want to disclose it to anyone? Who’s going to find out? What about NS, what about jobs?”

He also felt extremely isolated: “I had no one I felt I could trust to talk to. I also told myself that this happened because of my decision… So I didn’t really contact anyone, I just [kept] my thoughts to myself.”

It was this experience that strengthened his resolve to give back to the community, as he realised that there were others going through the same struggle he faced.

“I [told] myself, whatever the result is going to be, I am going to talk about this… I need people to know about this, because I didn’t know how people living with HIV (PLHIV) go through the whole pain and process, until I lived it for myself,” he recalls. He was eventually diagnosed with HIV, and started receiving treatment soon after.

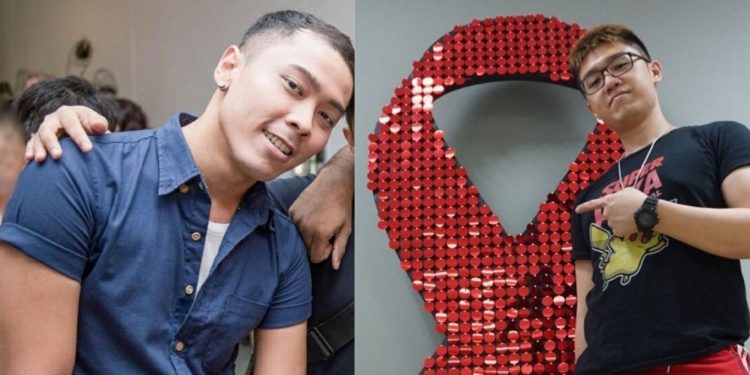

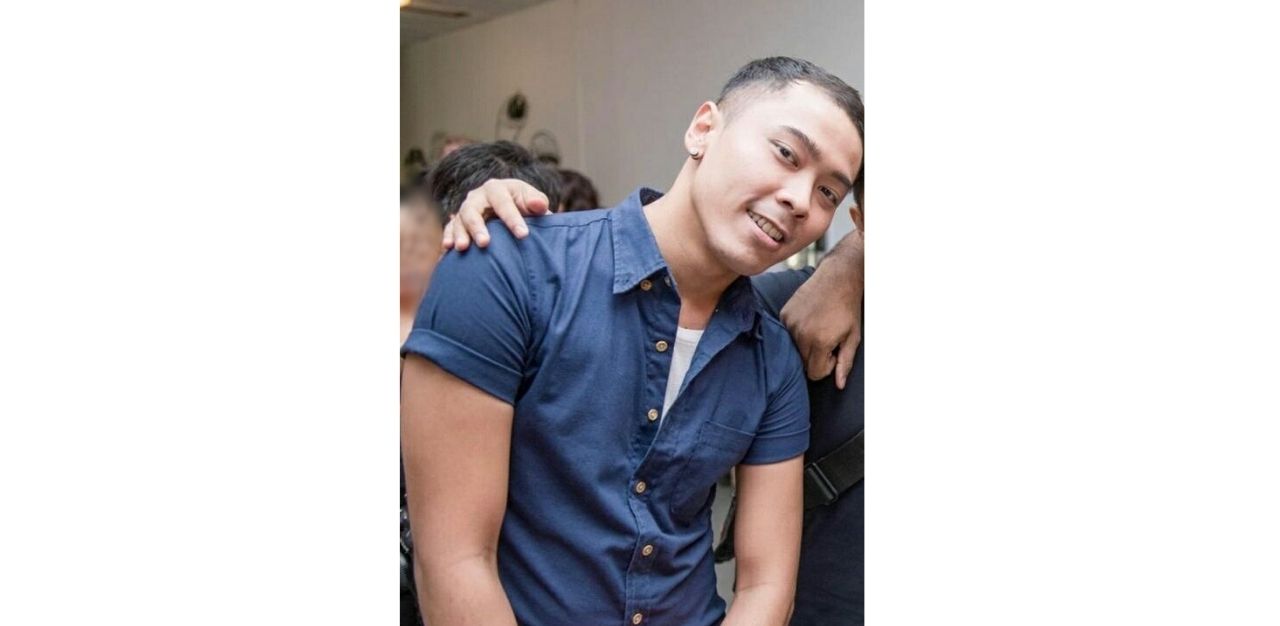

Today, the 25-year-old is a senior coordinator who handles the AfA Men who have Sex with Men programme, where he has been working since 2018 to support efforts for HIV prevention.

According to the Ministry of Health, 261 new cases of individuals with HIV were reported last year, with a total of 8,879 Singapore residents reported to be HIV-infected as of end 2020. While close to 400 to 500 new HIV cases were reported yearly from 2007 to 2017, this has since decreased to approximately 320 new cases a year in 2018 and 2019.

Leading the charge for change is HIV advocate Adrian Tyler. Along with Mr Tan, Mr Tyler is one of five people in Singapore who are openly living with HIV.

He was first diagnosed in 2016. “I attended a closed door event for persons with HIV sharing their experiences,” he says, adding that he decided to get tested when he learned that AfA was offering complimentary HIV tests at the time.

He began harbouring thoughts of suicide after receiving a positive result: “I was standing in front of the window, texting a very close friend of mine. And he called me just to check on me… He said words of encouragement [like] ‘You have a long journey ahead of you’.”

The 30-year-old now works as a Youth Coordinator at AfA, where he runs a drop-in centre for young Gay, Bisexual, Queer or Questioning (GBQ) men with his team, and conducts support group meetings and workshops on sexual and mental health.

While the HIV community still faces stigmatisation, he shares that the climate has since changed: “Overall, [from] 2015, 2016 till now, I can definitely say that society has improved in [its] attitude towards other people with differences.”

Still, misconceptions abound with regards to HIV and the HIV community.

Challenges and stigmas faced by the HIV community

Misconceptions over the mode of transmission is an obstacle that the HIV community faces. These include the belief that one can contract the virus by interacting with others who are living with HIV.

“It’s [a] ‘I touch you, then you get HIV’ kind of misconception,” says Mr Tan. “That’s the predominant one and the funniest one. Because most of the time, you can only get HIV through sexual contact with [a] person who is HIV positive, and doesn’t have a fully suppressed viral load in [their] body.”

Mr Tyler concurs: “Up to this day, clients will ask us whether they can get HIV through hugging, sharing of toilet seats, sharing of utensils.”

He adds that there is the misconception that HIV is a “gay disease”, even though HIV can be transmitted among those in the heterosexual community as well.

There is also the assumption that HIV is a “death sentence”, as some are not aware of the differences between HIV and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). While HIV is a virus that attacks the immune system, AIDS refers to the most severe stage of HIV infection, and can occur when treatment is not sought for HIV.

Mr Tan shares that conducting outreach to the HIV community has become more difficult due to the pandemic.

“We [used to] go to bars [and] clubs to provide complimentary HIV testing to patrons, because not everyone wants to go to a clinic to get tested. We [even] have a mobile van to ‘bring’ the clinic to them,” he explains.

“Thanks to Covid, we have a [lot of] difficulty trying to do that… Because bars and clubs are restricted… Without these nightlife venues, we can’t really reach out to our target audience.”

Rejection, especially in the dating scene, is yet another common issue that Mr Tan has faced.

“When I disclose my status to [potential sex partners], there is a 95 per cent chance that they will say, ‘Okay, sorry, I’m not interested anymore’… It’s constant rejection all the time,” he says.

Others question him incessantly when they learnt of his diagnosis.

“When I tell them I’m positive, it will immediately turn into a Q&A session… They don’t want to know who I am as a person. They [would] rather know my status,” he says. “It’s very difficult to find someone who wants to know us as ourselves.”

“They are mostly curious. But it’s how they ask [the questions], like ’How [did] you get it?’ And ‘Are you still sick, are you still dirty?’”

Mr Tyler agrees. “They keep using the word clean, like, as if people living with HIV are dirty. I shower, okay!” he says, laughing.

Both Mr Tyler and Mr Tan have also been discriminated against, even within medical professional settings. During a visit to a polyclinic, Mr Tan encountered a nurse who attempted to report him to the police upon learning that he was living with HIV. According to the Infectious Diseases Act, PLHIV are required to disclose their status to partners prior to engaging in sexual activity.

“I told her I’m positive, then she went to use the phone. As she was calling, I deduced that she was calling the police to report me for not declaring my status to the other person, [and] immediately told her that [my sexual partner] is also positive,” he says.

“She just said ‘tsked’, slammed the phone, gave me some antibiotics and sent me out.”

Similarly, during a visit to a medical institution, Mr Tyler came across a question requiring him to declare his status while filling up a form.

“[It asked] ‘Do you have anything to declare [such as] other illnesses [like] cancer’… At the end [of the list, it indicated] AIDS instead of HIV. I was trying to understand why they had to ask about my HIV status. There’s no reason for them to actually put that in the form because all the equipment that they use has to be sterilised no matter what.” After raising the matter with the doctor, he noticed during his next visit that the option had been removed from the form.

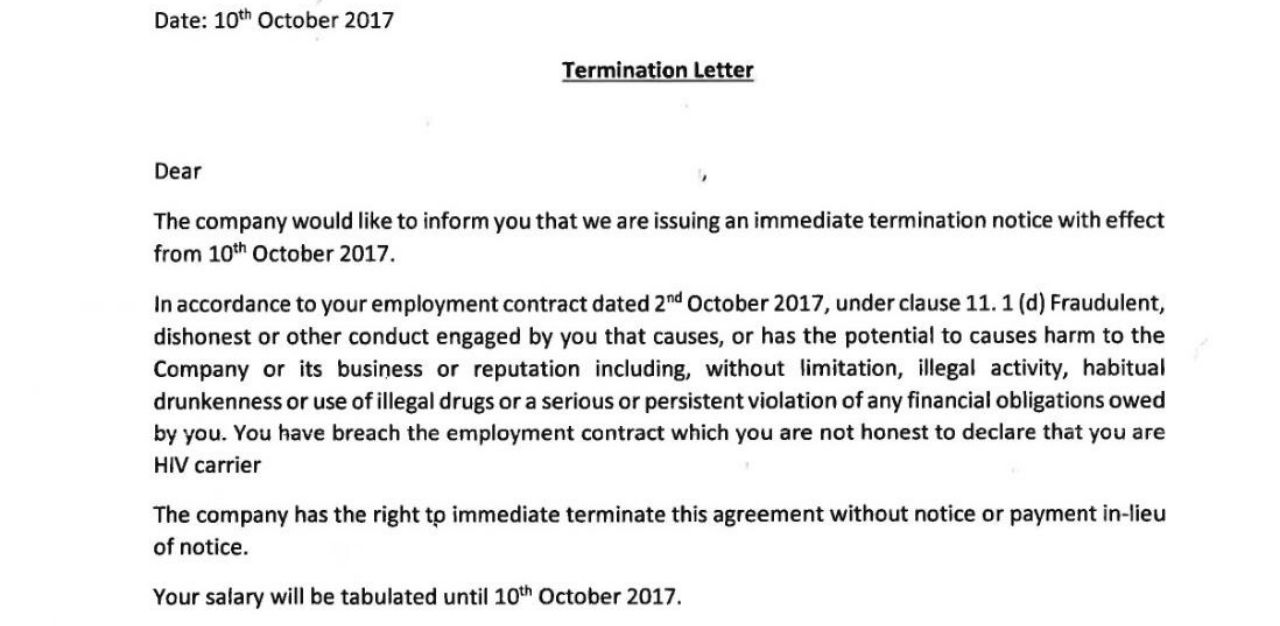

He has also encountered challenges at the workplace. He was once terminated from his position for failing to disclose his status during an interview with his former employer.

“It’s not the virus itself that kills us, [but] more of the stigma [and] discrimination that society has towards us,” opines Mr Tyler.

The need for change

Mr Tyler believes that there is a need to promote awareness of such issues the HIV community faces, even the transmission of HIV.

One such topic is the U=U (Undetectable equals Untransmittable) message, which states that undergoing effective HIV treatment reduces the levels of HIV in the body (viral load) to extremely low. This is a condition known as viral suppression. Individuals who are found to have below 200 copies of HIV per millilitre of blood are referred to as having an undetectable viral load. Under such conditions, there is effectively no risk of transmission of HIV through sexual contact.

“If a person living with HIV is on medication and treatment, if [they] were to have sex with someone, even without a condom, [they] won’t transmit [the disease],” Mr Tyler explains.

While social media pages such as UequalsU SG are promoting this issue to combat the stigma surrounding HIV, he says that greater awareness for the general public is still necessary.

“Whenever we conduct workshops about personally dealing with HIV, [those] who attend are people who already know about HIV and U=U,” he explains, adding that he aspires to be a part of a nationwide campaign on U=U in the future. “Our challenge is to reach out to people who don’t know [about who we are and what we do].”

It is also vital for the public to be more sensitive to and knowledgeable about etiquette when talking to PLHIV.

For instance, Mr Tyler shares that one should not ask PLHIV how they contracted the virus. “Some of them [contracted] HIV through sexual assault. So when you ask someone how [they] get HIV, it could trigger bad memories,” he says.

“[Questions such as] ‘How long do you have?’,‘Who gave it to you?’ [and] ‘I’m not getting it, am I?’ [should be avoided]. The things that you should say when someone disclose their status to you [include] ‘You’re not alone’, ‘Have you started treatment yet? I’m here for you’, [and] ‘Have you found a good doctor? I appreciate you telling me that’.”

More financial support for the HIV community is also key, says Mr Tyler: “Medication is very expensive; [it costs an average of] $600 (USD $442.12) a month. They recently announced a subsidy for [HIV] medication, but it still [costs] quite a lot of money.”

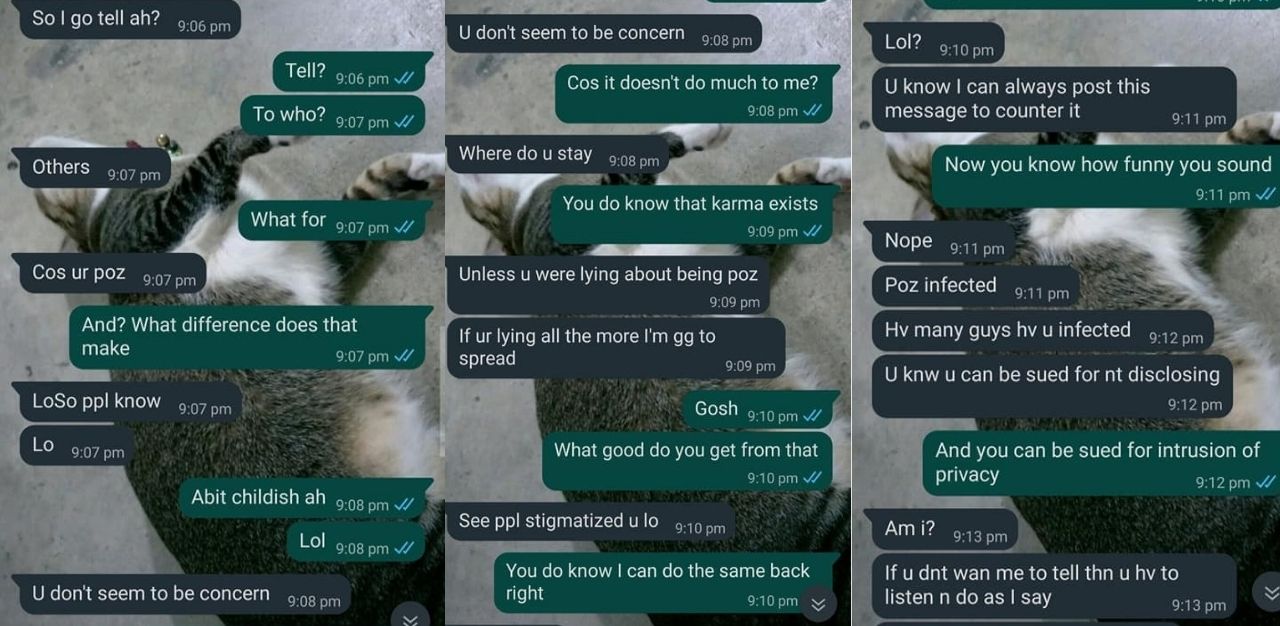

Mr Tan asserts that there is a need to introduce policies to protect and safeguard the HIV community, citing the example of a person who attempted to blackmail him by threatening to spread the news of his status.

“A few years back I was talking to someone on a social app, and they asked me, ‘Are you that person with HIV?’ What’s it got to do with knowing who I am?,” he says.

“[There needs to be] laws or policies to protect, prevent us from getting [into] that kind of situation because it’s still going on.”

Such behaviours are part of the reason that very few people in Singapore are living openly with HIV, he says: “That’s also why there’s only a few of us who are out about our status in the first place.”

Hope for the future

Mr Tyler finds great fulfilment in learning from his clients and watching them grow. And according to him, he is also learning from them.

“We don’t expect anything in return, [but] it’s really nice to see that they have come so far. When we meet clients, we learn new things as well. It’s not just us guiding them,” he says.

He believes that to be Singaporean is to be inclusive: “To be able to love anyone without fear, to be able to get married here with my partner if I were to have one.”

A sense of satisfaction from helping others and it is what drives Mr Tan’s passion for creating change.

“Every time someone reaches out and thanks me for what I do [for him], that fuels me to continue, keeps me going. As long as I can provide that comfort [to] at least one person, then I’m satisfied with what I’ve done so far,” he says. “I have made a difference by being the difference.”

And for him, being Singaporean means living peacefully with others – in spite of their differences.

“Regardless of any difference that I have with someone else, we still coexist together as [one] people, because that’s what we are. Whatever we prefer, whatever differences we have, is what makes us uniquely us.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.