For the average hearing person, subtitles at the movies would either irritate or be little more than a bonus aid.

It would likely, then, be a revelation of sorts that captions and subtitles are not the same things, and that certain kinds of captions barely benefit the deaf community.

For deaf person Jessica Mak, 44, the absence of captions automatically opts her out of an existing selection of TV shows or videos. “I rarely watch television, because most of them don’t provide subtitles or captions,” she says.

Ms Nix Sang, a team leader of disability inclusion consultancy Equal Dreams, says there are key differences between captions and subtitles.

“Captions capture 100 percent of the original spoken content, and also include meaningful description of any aural information and speaker and sound source. Subtitles seen on local TV channels sometimes censor away or edit words or phrases. This compromises full access for the Deaf or Hard of Hearing (DHOH) community,” she says

For example, when watching a Singaporean Chinese drama with English subtitles on Mediacorp Channel 8, the subtitles translate every line spoken in Mandarin, but exclude all those spoken in English — which left Ms Mak lost in translation.

Sound descriptions, or speaker identifications — especially those off-screen — are all the more key for some forms of content to even make sense for the DHOH.

“Whenever my deaf friends and I watched a horror movie, we didn’t react when other hearing people screamed or jumped,” says Ms Mak. “We were puzzled about their reactions until our hearing friends told us the eerie sounds caused them to behave like that.”

Due to the speed of delivery, other presentation factors also contribute to the accessibility of captions — such as font size, type, colour, and background. “There are a few videos that provide captions in very small fonts that make it very difficult for us to read, especially for those of us with Usher Syndrome — a genetic disorder that results in a combination of both hearing loss and visual impairment,” she adds.

Strides in Singapore

Accessibility for the DHOH community has undoubtedly come a long way in these past decades. Even rap concerts now have sign language interpreters, and yes, deaf people still enjoy live music events via the vibrations of the sounds.

Here in this island republic, calls for more accessible captions have not gone unnoticed. In 2013, deaf person Alfred Yeo relentlessly wrote to movie production companies and cinemas requesting captions for the Deaf so they, too, can enjoy English movies.

“In the past, English and non-Chinese movies always only had Chinese subtitles, and most of us were educated in English only,” says Ms Mak.

That said, there are still ways to go in building a truly inclusive and conscientious captioning system — the very thing one would expect the needs of the deaf community to be able to take the forefront of.

“While the deaf can now enjoy watching movies, the timing, location, and selection of movies with English subtitles are very limited. So we have to apply for leave and go to very far places like Vivocity, if we live in the North, for example,” says Ms Mak.

Adapting to the new norm, video conferencing platforms like Zoom, Google Meet, Microsoft Teams, and Skype now also have auto-captioning functions — but they are seldom very accurate. “During work meetings, I am only able to understand about 70 to 80 percent of the conversation without knowing the context. But deaf people are good at guessing, and it’s better than nothing,” she says.

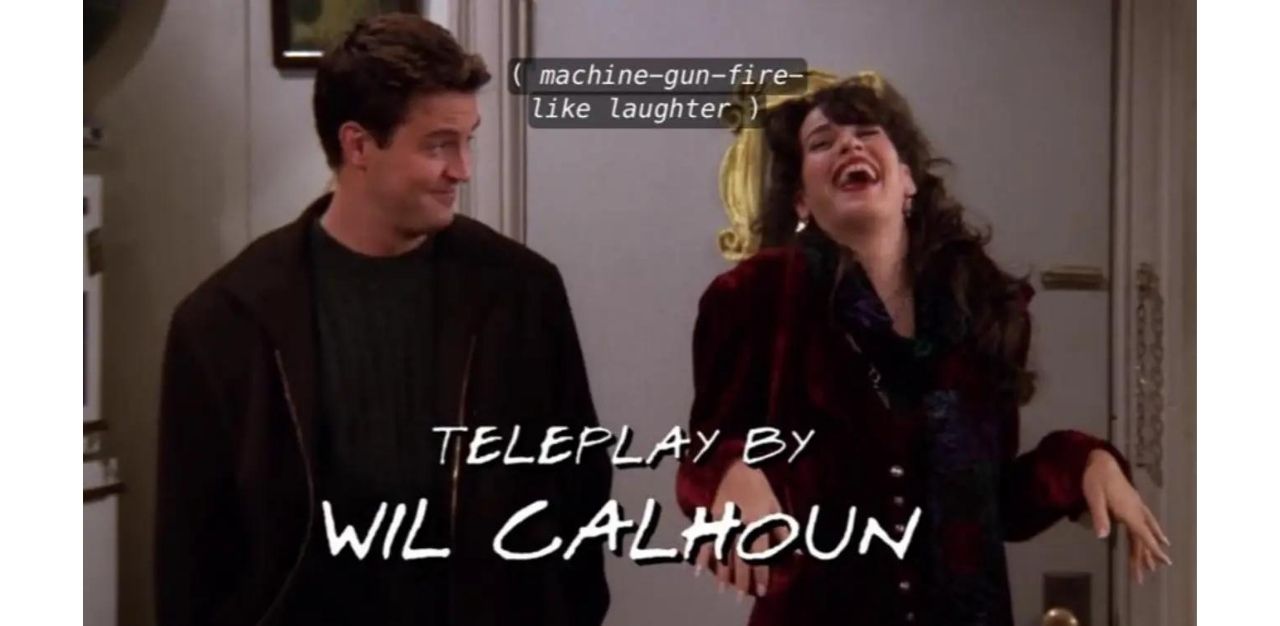

Good captioning borders on being an art, the same way translation does — Ms Sang says it’s not as straightforward as simply being able to capture every single word, or describing sounds literally.

“Context is important. When the speech is fast, how do we capture all of it, yet not let it flash too fast in each frame? How do we describe the sounds, tones, and music meaningfully without dictating the audience’s interpretation, while letting it stay true to the sound designer’s intention? How do we avoid an early reveal of a joke or a punchline?” she asks.

A movie released in 2021 aimed to change that. Called CODA, which is short for children of deaf adults, it is a coming-of-age story about the only hearing member of a deaf family. The film was shown with captions that require no special equipment to see.

Deaf actor Marlee Matlin, who played the mother in the film, said, “It couldn’t be more groundbreaking.” And deaf actor Daniel Durant, who played son Leo, added, “This is a day we have waited to see for so many years.”

The award-winning movie’s writer-director Sian Heder, who can hear, learned American Sign Language for the project. She wanted to be sure CODA was available for everyone to watch and enjoy.

“Oftentimes I think deaf people are left out of the movie-going experience because of devices that don’t work and lack of devices in theatres,” Heder said.

Preferences might vary from deaf person to deaf person, Ms Sang says. While there are common international guidelines, working closely with local deaf communities and constantly seeking feedback is what she thinks is the key to accessibility.

In November 2012, Singapore ratified the United Nations’ Convention of Rights of Persons with Disability (CRPD), with the purpose of ensuring that persons with sensory disabilities have equal basic access to information (Articles 9 and 21). Sadly, many like Ms Mak still find many things inaccessible to them, and envy their foreign deaf friends who have better access to TV, movies, and events.

“Deaf people are human beings — and just like everyone else, they want to enjoy things together with their family and friends, regardless of their disability. I hope to see more captions in the media and at events that will make our society more inclusive,” she says.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.