[NOTE: This op-ed was first published on Ms Er’s Medium page here.]

The number of new Covid-19 cases in the community jumped from less than 10 cases in March, to more than 360 from 2 to 23 May, in what has been labelled the “worst Covid-19 outbreak in Singapore”, since 2020. The first cluster highlighted was in one of Singapore’s largest public hospitals, Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH). Unfortunately, the way the news was reported gave people the impression that a nurse in Ward 9D, who was the first case detected, was responsible for the TTSH cluster, when she was just like any other person who caught the virus.

As the cluster at TTSH grew larger, some Singaporeans began criticising our healthcare workers, and targeted nurses in particular. The increasing criticism and discrimination seemed to reach such a level of terrible intolerance that Kenneth Mak, Ministry of Health Director of Medical Services, had to urge the public on 4 May not to shun healthcare workers. Some nurses were told that they were not welcomed at their place of accommodation. In fact, nurses like Nigel Rankine, who works at TTSH, shared how some hotels turned him away when they found out he was a nurse. Others recounted not being able to get rides home from taxi drivers.

Very quickly, what used to be public love and adulation for nurses and doctors turned into outright discrimination. In 2020, the media, schools, and the public had organised lovely efforts to recognise the sacrifice that nurses and doctors made, and often used the label ‘healthcare heroes’ to praise and thank them. On the surface, such language seems to convey a high level of praise. But, such language also reinforces society’s sense of entitlement to unreasonable expectations of healthcare workers.

Why ‘heroes’ can be a damaging metaphor

In Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff argues that metaphors are powerful in shaping the way we view and interact with the world. The language we use often informs our understanding of the world, and without a critical examination of our language use, it is easy to continue perpetuating harmful ideas and practices.

In popular culture, our symbols of heroes are often those found in the Marvel or D.C. Universe. Our understanding of heroes is shaped by the characterisation of emblematic figures, like Superman, Spiderman, Wonder Woman, etc. What these heroes have in common are:

- They are endowed with supernatural abilities.

- They make huge personal sacrifices for the good of humanity.

- They are unaffected by the criticisms and discrimination they face by an ungrateful society and will continue making such sacrifices.

While it might seem like huge praise to call our doctors and nurses ‘heroes’ in such a time, it also perpetuates the idea that they are superhuman. The differences between our doctors, nurses, and our fictional heroes are:

- They DO NOT have supernatural abilities.

- They make personal sacrifices, BUT it is not an entitlement. ‘Doctor-ing’ and nursing are JOBS. Let’s not forget that.

- Doctors and nurses are human. Criticism, discrimination and abuse naturally affect their morale and can have huge implications on their mental and emotional health.

The lived reality of doctors and nurses can be hell

An article I wrote recently on the unreasonable working hours of doctors in Singapore went viral among the medical community, and I received many messages from junior doctors relating their own lived experiences. Some of these junior doctors find some relief in humour – there are quite a few wonderful meme pages out there that express the challenges they face and find some comfort and solidarity among their peers.

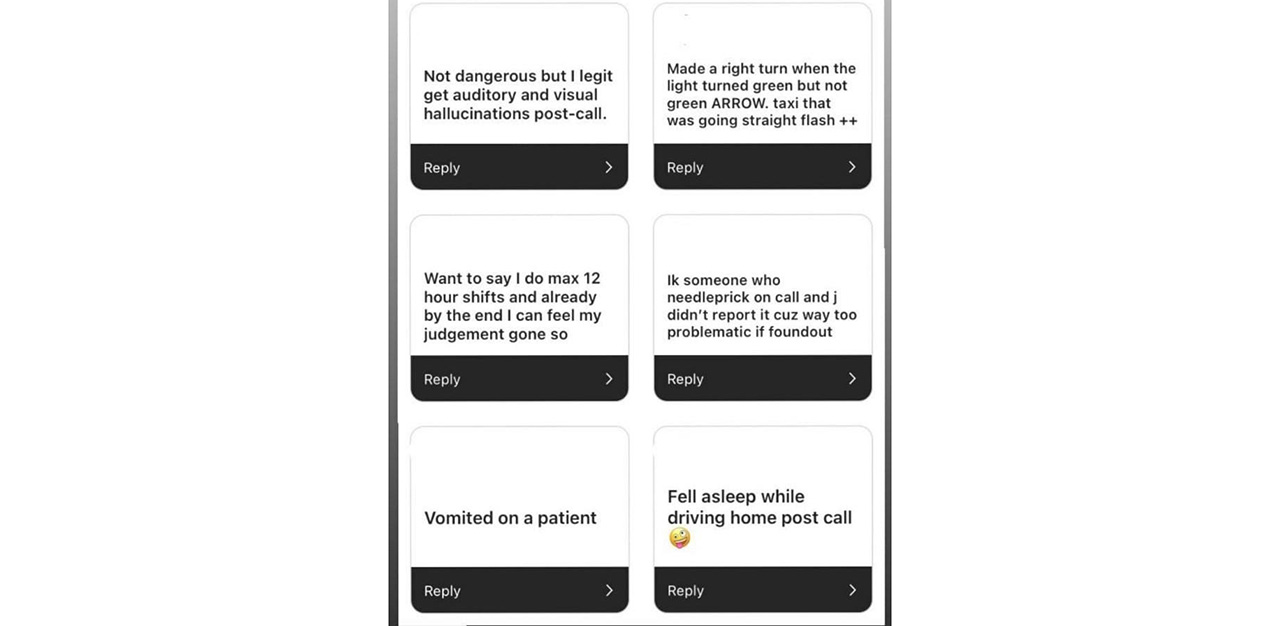

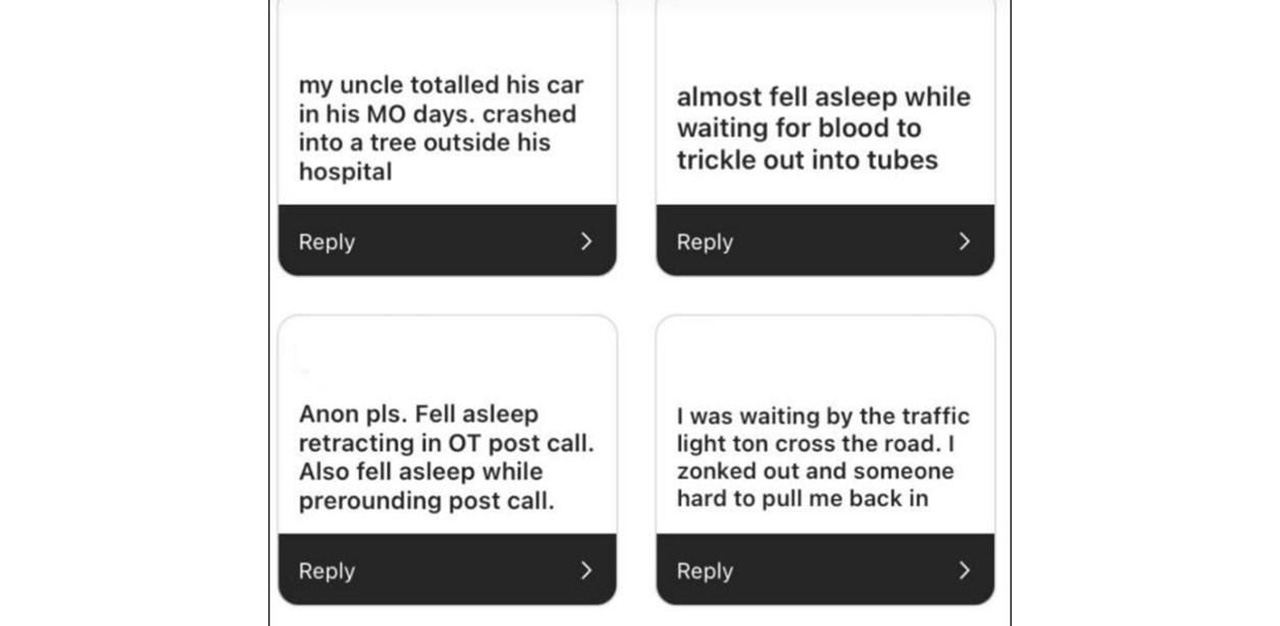

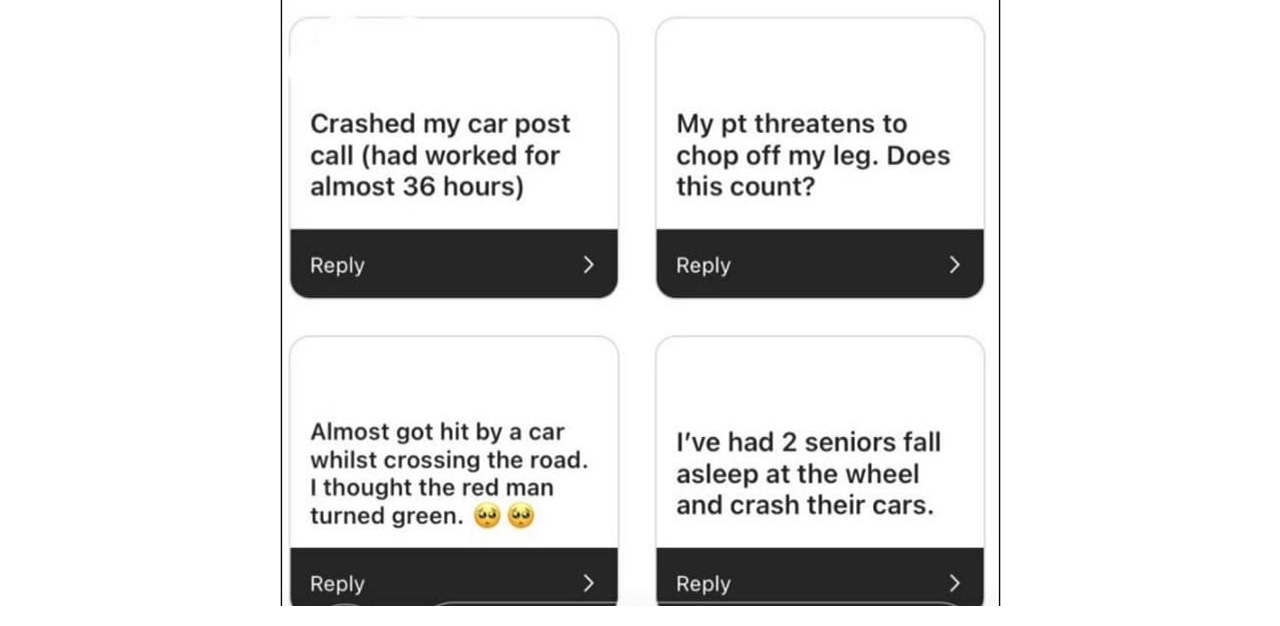

Thanks to a junior doctor who runs one of these meme pages, we got some data on how hellish these expectations of their abilities (i.e. working 30-hour shifts) can be, and the very real dangerous impact it has had on their lives.

The question on the Instagram story was, “What is the most dangerous thing that has happened to you on call?” Among the 19 personal responses; eight of them recounted getting into car accidents and mishaps; two made mistakes in dispensing medicine and treating patients under their care. One doctor recounted being threatened by a patient, who vowed to “chop off” his legs.

Rice Media ran a revealing interview of a junior doctor’s lived reality, where the doctor recounts his struggles with working a 100-hour work week, and having to come face to face with earning less than someone who works at a bubble tea shop. While some netizens started criticising the doctor for “whining” and having an entitled mindset, what many don’t see is that these doctors often have S$50 to S$100k student debts to pay off and families to support. These are serious systemic issues that require closer examination, because it is faced by all junior doctors in the public healthcare system and is clearly a cry for help to address these problematic systems, before all doctors burn out and require mental health treatment.

Similarly, nurses face a ridiculous work schedule, and the abuse they have to tolerate is unspeakable. I remember hardly seeing a dear friend who was working as a nurse because she only knew her shift every two weeks, and they were often put in odd hours. She had no social life. I have also witnessed how rudely nurses are treated in hospitals. They are shouted at, threatened, and are expected to be at the beck and call of demanding patients who often go, “Missy, MILO PLEASE! WHERE IS MY MILO?!” (I am pretty sure that cup of Milo is not a need. These are healthcare workers, not servants.)

Healthcare workers are doing jobs, just like you and me

While we might be tempted to think that nurses and doctors are here to serve society, there must be limits to the expectations we have of them. Just like you and me, these are jobs, not voluntary missions they take on. They are humans, not superheroes. With this mindset, what kind of questions might we have for jobs like nursing and ‘doctor-ing’?

- What are the job scopes of nurses and doctors? (e.g. Do we expect nurses to always serve milo instantly?)

- With their relevant accreditation and knowledge and the amount of work expected of them, what is a reasonable salary?

- Why are labour hours set out by the Ministry of Manpower not followed for nurses and doctors? Why are they excluded from such regulations?

- Do they have sufficient time to eat, visit the washroom and drink water?

Recommendations

I once attended a dialogue session with Singapore Health Minister Ong Ye Kung, who said something that has stuck with me since, “Don’t just complain, provide solutions.”

And so, these are some ideas that I have. I believe doctors and nurses could also provide meaningful input to create a healthier healthcare system for both workers and patients alike.

- The Ministry of Health could gather a few officers to form a team to investigate the issues faced by doctors and nurses. Focus groups within each hospital should be formed, and doctors and nurses should be allowed to air their views and grievances, with no penalty, within these closed-door sessions.

- Examine other healthcare systems around the world like Australia, which monitor the working hours of doctors strictly. How are they ensuring that regulations on work hours and safety are enforced? What systems do they have that we can learn and borrow from?

- Set up a committee made up of junior doctors and nurses to guide the team doing the review. Without their input, it will be a meaningless exercise.

I’m just a Singaporean, what can I do?

While things need to change on a systemic level, all Singaporeans can play a part to make changes, particularly in the way we treat our doctors and nurses.

- Stop calling them heroes – recognise that they are doing a job.

- At the hospital, when you can, genuinely ask how they are doing.

- If you are a family member or friend, check in on their emotional and mental health. Ask how you can help them, even if it means sending a bubble tea drink to cheer them up.

Finally, I think our main guiding principle should just be: Be Kind. There is no need to organise mass clapping sessions, or to send dozens of cards to nurses and doctors to show appreciation (of course, you can if you want to). While these are sweet gestures, true gratitude goes beyond lip service. We need to change what is currently not working, so that our society can be a healthier, kinder and more compassionate one.

[Correction: We have removed this part of a sentence “the spread was traced back to a nurse working in Ward 9D” to avoid any misunderstanding that Ward 9D was the source of the infection in the TTSH cluster.)

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.