In the North East corner of Singapore lies a slice of land unperturbed by the passage of time, seemingly immune to the relentless march of our island nation towards progress. Nestled between the gleaming new HDB BTO (build-to-order) flats and an upmarket private housing estate is Kampong Lorong Buangkok.

Low-rise, one-storey houses are still the mainstay here, an antithesis to the relatively small, stacked units we now live in. Houses are constructed with hand-painted, wood-panelled walls, shielded against the brutal rays of the sun by zinc roofs. Along the meandering concrete walkways stand exposed power lines and street signs with four-digit postal codes, nary seen elsewhere on our island city today.

Nature weaves in seamlessly with the homes (Kampung in a Garden, perhaps, rather than Garden in a City); fruit trees grow in abundance, chickens roam freely, and a lone monitor lizard basks, a watchful eye on the stray chickens that could be its next meal.

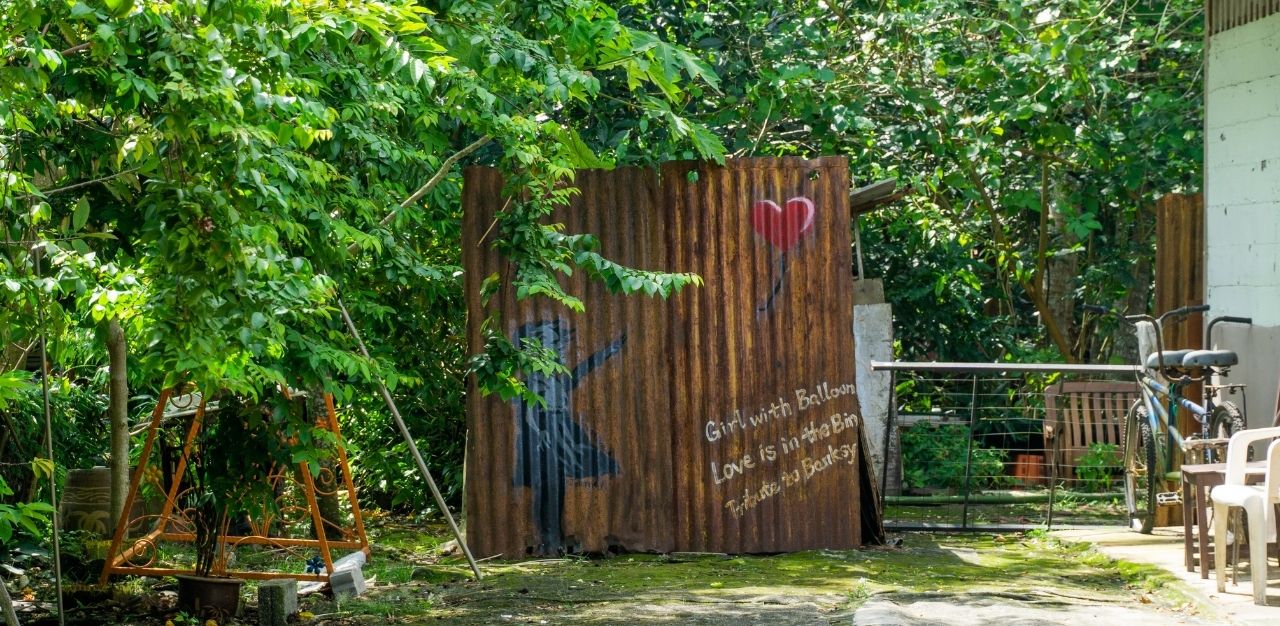

Occasionally, bright pops of colour shine through – rainbow fences, turquoise and pink walls, and even a tribute to infamous street artist Banksy, painted on a rusted metal sheet. An idyllic oasis within a bustling cosmopolitan city, the 1.22ha of land is a living, breathing time capsule.

There is perhaps nowhere else in Singapore more apt to discover the elusive kampung spirit than here, within Singapore’s last kampung.

But on a weekday afternoon, the kampung is quiet save for the occasional crow of a rooster. The odd resident sits at their spacious patio, reading a newspaper, a dog at their side. In the centre of the village, a quaint mosque comes into view. Here, two men sit, conversing quietly – the first sign of human interaction, but not quite an embodiment of the kampung spirit I was looking for.

Continuing on my jaunt, I venture deeper into the village, off the demarcated paths and onto unruly grass. One step in, and a voice calls out to me in Mandarin: “Did you see the monitor lizard?”

I glance around, seeking a sign of the long-tailed reptile or the owner of the voice.

“There, the one stalking the chickens!” she adds, upon seeing my confusion. It is only then that I notice her – an elderly woman sitting on a rocking chair at her patio, grinning at me. She points towards the dense undergrowth, directing my gaze toward the monitor lizard, which had been startled into stillness by the ongoing commotion.

“I see it!” I tell her.

“It’s lucky you walked by. Or else the chickens will become food already!” she laughs in response.

Small talk ensues, as she shares more about the nefarious monitor lizards that have been plaguing the chickens in the kampung.

This is the only glimpse of the elusive kampung spirit that I will witness in Kampong Lorong Buangkok, difficult as it is to pinpoint something so intangible in one short afternoon. But my interaction with the lady is undoubtedly different from those with my neighbours within my estate. Her disposition was affable and welcoming, and she readily welcomed further conversation, a far cry from the brief smiles and occasional greetings I share with my neighbours.

With little luck in the Kampung, I turn my attention towards the homes of today, seeking out residents who can shed light on just what the kampung spirit is, and whether it continues to exist in our modern-day island city.

Finding the kampung spirit in modern-day Singapore

A quick search online will reveal that the kampung spirit is not just existing, but flourishing, especially during pandemic times. People are still helping others in various ways – the sharing of hand sanitisers and alcohol wipes within a Punggol estate, a #KampungKakis initiative to befriend the elderly and vulnerable during the pandemic, or shared gratitude towards frontline workers.

Two initiatives, in particular, stood out to me: the Unmanned Free Food Pantry helmed by Ken Yeo, and The Little Library, spearheaded by Yvonne Looi. While the two started as small family initiatives, both have since spread across the city, sprouting up in a number of estates, and spreading the kampung spirit across the nation.

Intrigued, I speak with Mr Yeo and Ms Looi to learn about the inspiration behind their operations, and what the kampung spirit means to them today.

Spreading food and the kampung spirit nationwide

The seed of Unmanned Free Food Pantry had lain in Mr Yeo’s mind for “the longest time”. Popular in other countries like the United States, Australia, and the Philippines, Mr Yeo was drawn to the idea of pop-up pantries enabling the less fortunate to collect daily necessities and groceries they may need on their own terms.

But a fear of such pantries being looted or items being taken by those who it is unintended for plagued him, preventing him from starting one of his own. The pandemic changed his mind, as the rising number of jobless and news of beneficiaries not benefitting from mass-distributed care packs (which may fail to take into account the varying needs of different families) convinced him that such ad-hoc pantries had the potential to help many.

The first food pantry was thus set up as a small family project at Spooner Road on 27 August 2020, in the hopes of benefitting the needy in the neighbourhood. To his delight, it turned out to be a huge hit with the residents. Riding on the success of this venture, they established a second pantry at York Hill. Soon enough, the media picked up on this initiative, skyrocketing its popularity islandwide.

“When news broke out, I was overwhelmed with emails. Many expressed support, contributions, and queries on how to set up a pantry,” Mr Yeo shares. “I was delighted to guide [those interested in setting up a pantry of their own], and a few of them did go about [doing so].”

He adds that this was a welcome sight, as he had hoped for the mushrooming of such food pantries all across the country when he initiated the first Unmanned Free Food Pantry. Unfortunately, the initiative was short-lived, as many of these ad hoc pantries “fizzled out as the novelty wore off”.

Undeterred, Mr Yeo continued to set up pantries alone, and eventually had the idea to create a central stockpile of groceries. Leveraging on his day job as a minimart owner to procure groceries at wholesale prices, he is able to stretch his dollar to help more beneficiaries. This allows interested parties to set up pantries in their own neighbourhoods by drawing on the stockpile, instead of having to purchase their own.

“All they need is a car (and manpower) to transport the groceries to set up locations,” he explains. “I am able to reach out to more areas, and volunteers and their families can get their give-back-to-society needs fixed.”

Such pantries hark back to the “good old days”, says Mr Yeo, alluding to the kampung spirit I have been trying to uncover: “Back in the [day], neighbours would share excess food to those in need. Same concept here. When we set up pantries, beneficiaries will always run up their blocks and tell their neighbours to come take a look, and some would help take some groceries on behalf of the handicapped elderly.”

“That is [an] awesome kampung spirit,” he states. “You can see residents…striking a conversation with the person beside them. You don’t see any pushing or fighting over the groceries.”

He opines, “The kampung spirit is still very much in us… It is the indispensable thread that binds the social tapestry [of a] nation.”

In his own ways, Mr Yeo hopes that the Unmanned Free Food Pantry movement will help rein in the income gap, and help those left behind “quickly find their foothold”.

“If we cannot help everyone, at least we can help someone,” he says. “Improving the community will improve the country as a whole.”

The gathering of a community, bonded by a love of learning

The kampung spirit today may no longer be found within one-storey houses, but can perhaps be witnessed far higher up in the air, at the lift landing on the 39th floor of 27 Ghim Moh Link.

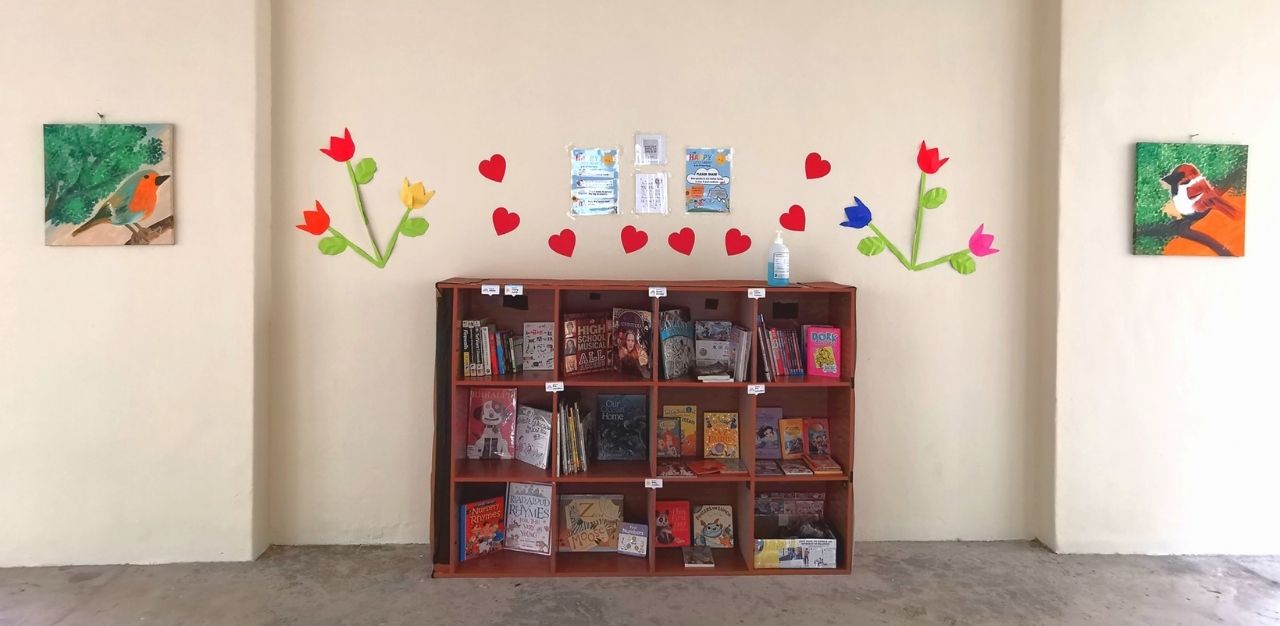

Here, you will find a cosy corner comprising two shelves filled with children’s books, alongside an infusion of nature: caterpillars and tadpoles in self-contained habitats for children to learn from.

Ms Looi’s words set the scene of what a modern-day kampung could be: Grandchildren nestled on the laps of their grandparents, listening to stories come to life; curious eyes peering intently at caterpillars munching away, the same eyes widening with wonder as butterflies emerge from pupae and spread their wings; groups of children coming together to play, read, and bond.

It is a reality she has created through The Little Library.

The Little Library’s journey started at the rubbish chute, where Ms Looi had found a box of books sitting abandoned. As a book lover, she rescued it, and found a range of children’s books within. One book in particular stood out to her; it had a little Christmas note written on the front page.

“I felt that there was so much history and love within all these books, and it’s such a waste to not be able to share this with the next person,” she says.

This was how the idea of The Little Library sprouted. And so, in January this year, the full-time mother of two found a box and plant at home, and left the books at the lift landing outside. Whenever she and her family encountered others around the neighbourhood, they shared the news of this space. Slowly but surely, neighbours picked up on it, and more people started to visit.

What started as one shelf became two, and a nature corner was gradually incorporated as well, courtesy of the lizards, caterpillars and tadpoles thriving within the estate.

“The items from the nature corner [can be found] around our neighbourhood,” she explains. We wanted to show the children that nature and beauty is all around us, you don’t have to travel or go to hard to reach places [for it].”

Eventually, Ms Looi decided to initiate programmes to bring the community and children together. They started conducting read-along sessions and even handicraft workshops over Easter Day.

The growth of The Little Library has taken Ms Looi by welcome surprise: “It’s now beyond the neighbourhood. We have people who enjoy what we do here, and even though they live far away, they don’t mind coming if there are events.”

“It’s the community we are building that’s very precious, and something we want to have for our children growing up,” she adds. “We’ve been living here for five to six years before we had children, and we hardly know the people [in the estate]. But now, every time we go out, we will definitely see and say hello to at least two or three [families].”

She brings up a quote by poet William Butler Yates: “There are no strangers here; only friends you haven’t yet met.”

“[We are] slowly moving towards that,” she muses. “Wherever we go, we will find people who are really warm, who know us, and we know them. It goes beyond our usual comfort zone and into people’s lives and their hearts. That is the kampung spirit, and something I want our children to grow up with, especially in today’s world.”

Today, Ms Looi is aware of 15 to 20 little libraries that have sprouted across Singapore since starting her own humble corner at her estate, a heartening fact that confirms the continued proliferation of the kampung spirit in modern-day Singapore.

Indeed, my search for the kampung spirit may have started in the likely location of a space frozen in the times of old, but it ended with me finding it in the everyday.

As Ms Looi says, the kampung spirit is inherent within us: “The kampung spirit is in everybody, it’s just that sometimes, they need a platform, space, or reason to bring that out.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.