When she turned 30 years old, Samantha Tan decided it was time to move out of her childhood home. This is a perfectly ordinary thing to do in many other parts of the world: setting up your own home when you come of age is a common rite of passage.

But this is land-scarce Singapore, where affordable public housing is allocated to citizens through a lottery that requires you to be a straight married couple to be eligible to participate. The choice to privately rent a place of your own – a decision many equate to throwing money down the drain – can be a momentous one.

Yet, despite the hit to her finances and a sense of guilt for moving out of her parents’ home, Samantha ploughed ahead.

“I wanted to push myself to leave my comfort zone,” she said. “You can never really grow as an individual if you’re always cocooned in a safe and protective environment.”

Housing for a particular kind of family

To buy a Housing Development Board (HDB) flat, you have to be a particular kind of family. Like a good base recipe for bread or soup, there are ingredients that are must-adds: you begin with a husband and a wife, and then perhaps toss parents or children into the mix. If you’re single, then you have to wait until you’re 35 years of age before you can apply for a HDB flat.

Yet in societies like ours, marriage is a decision we make later and later in life, particularly for women. The median age at the time of first marriage in Singapore was 28.8 years old for women in 2019, slowly creeping up from 27.7 back in 2010, while the median age of men who tied the knot for the first time has stayed largely the same (30-30.4).

This is likely due to women becoming increasingly educated and more active in the workforce, but perhaps we’re also wising up to the fact that marriage isn’t all that great for women in the first place – behavioural psychologist Paul Dolan found that married women were less happy and lived shorter lives than their unmarried counterparts.

Marriage no longer has the same kind of appeal it had in the past. Our fertility rate is plummeting as people shirk the desire to have children. And not everyone in Singapore is straight or wants to get married.

So how relevant is the state-sanctioned model of family today? As family sizes shrink, parents age, and extended family networks fade, people are forming new communities beyond ties of kin and blood. And this means new types of households – formed in an attempt to get around Singapore’s housing policies.

READ: What Do We Lose When We Stop Speaking a Language?

HDB: the heteronormativity development board?

In the 1960s, Singapore was overwhelmingly made up of single male migrant labourers, sparking concerns about issues of overcrowding and poor sanitation. (A glance at our migrant workers’ dormitories today will show that this as a perennial problem.) The HDB was established to manage this problem, and they’ve managed it spectacularly. Almost 60 years later in 2019, Singapore’s home ownership rate is at 90.4 per cent, one of the highest in the world.

Historically, Singapore’s distribution of public housing – particularly in the political contestations of the 1960s and 1970s – has also been used to secure the stronghold of the People’s Action Party. For example, sociologist Chua Beng Huat noted that the ethnic quotas that HDB put in place for each apartment block disrupted any potential for ethnically based activism or challenge to the ruling party. Geographer Natalie Oswin added that the relocation of residents in Singapore to HDB blocks significantly improved living conditions for many, but also fractured networks of communist opposition and resulted in a loss of informal economies.

Public housing has also been used to perpetuate an ideal family model. Part of this was done by law – only ‘nuclear families’ could apply for housing – but part of this was also an ideological process. “The ‘proper family’ […] is central to key national narratives of modernity, progress and development,” wrote Oswin.

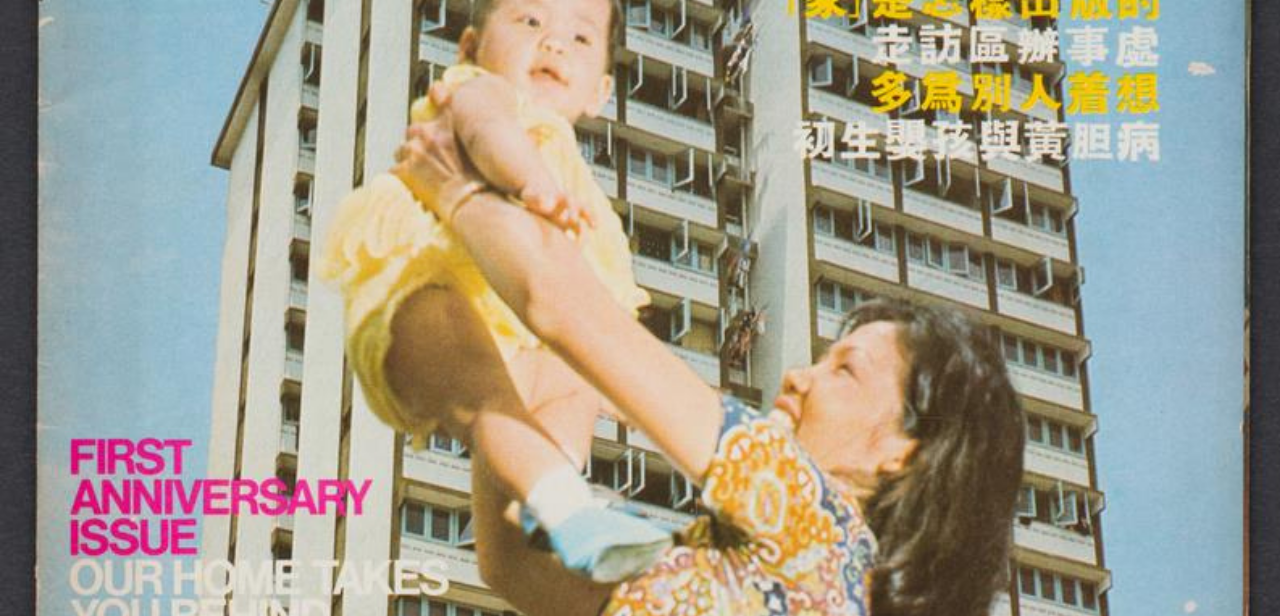

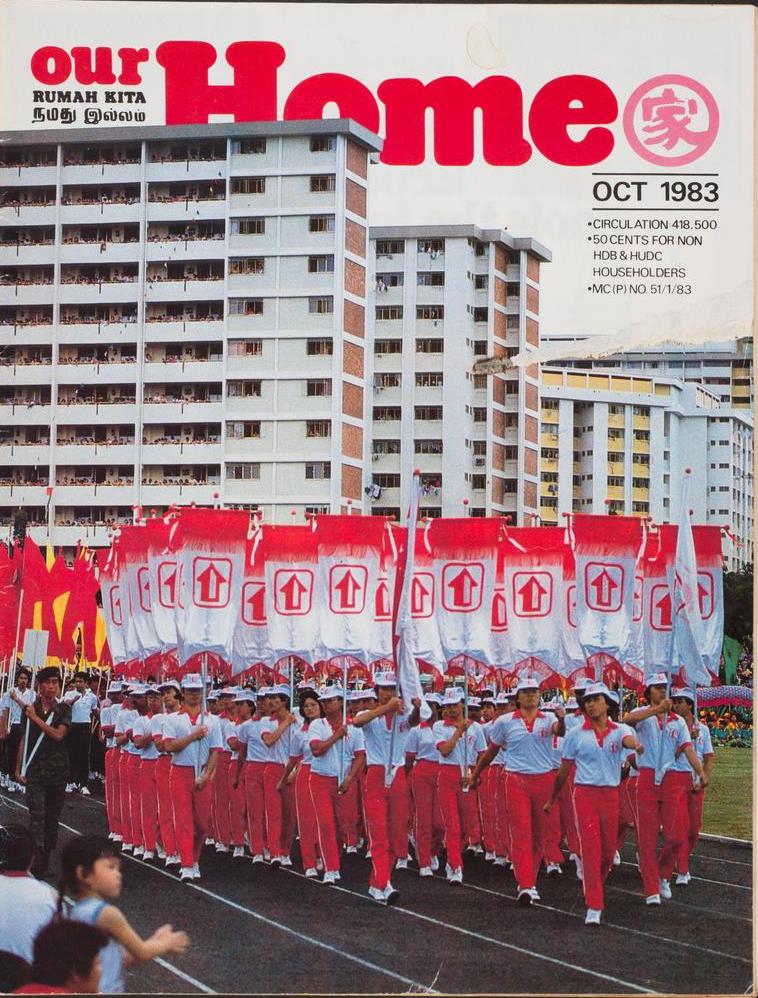

Noting that HDB archival records are open only to civil servants, Oswin found a creative way to track how HDB sought to influence and define Singapore’s families: she looked at copies of HDB’s in-house magazine, Our Home, which was produced and distributed to all HDB tenants between 1972 and 1989.

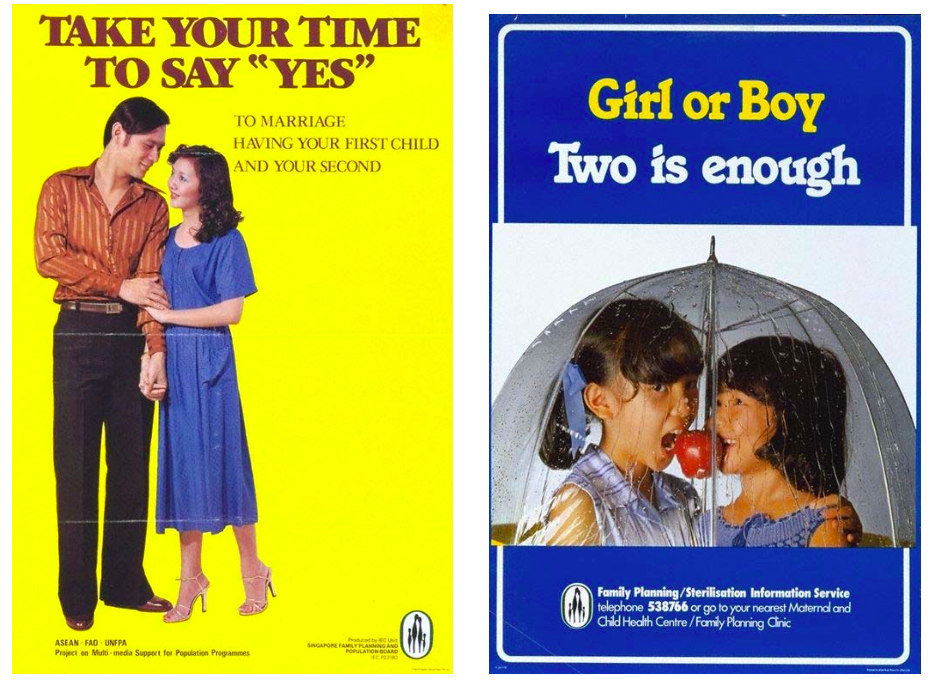

While policies today are pro-natalist – meaning that we want families to have children in order to prop up a rapidly ageing society – the focus then was anti-natalist, as the government sought to pare down on large families, particularly large families borne by poorly educated women who came disproportionately from Malay or Indian backgrounds (see Heng and Devan 1995 for more detail).

Oswin found that the magazines featured photographs of nuclear families on the cover, and that its contents were consistently focused on family size. Young couples were told that early marriage and child-bearing would create “agonising marital problems” and pregnancies that were “prone to complications”.

In one issue from 1976, residents were told that large families meant that children would receive less attention: “The love and care in a large family of six to ten children must necessarily be of a different kind and quality. Out of sheer necessity, parents are likely to run their homes autocratically…”

The nuclear family – two parents, two children – became the norm. It was, as Oswin wrote, “most literally put into place in the nation’s flats.” Housing policies are part of what makes heteronormativity an accepted moral principle in Singapore.

Heteronormativity is not simply a set of norms that makes heterosexuality the “right” thing, but particular expressions of heterosexuality seem right. This means that it’s not just about being heterosexual, it’s also about being heterosexual in the right way: it’s also about being married, with the right number of children, in order to qualify for a home.

Queer couples are explicitly excluded from this, but so are unwed, single parents and their children. While recent changes in the law have made housing more accessible to these family formations, they still do not count as a “family nucleus” and hence are not eligible for flats and housing grants. An AWARE report titled “Wives in Distress: Issues facing non-resident women married to Singaporean men”, published in 2020, also showed how migrant women struggle to maintain ownership of their HDB flats after their spouses pass away.

READ: Freedom of Speech in Singapore: What Does It Entail?

Moving out and becoming a work-in-progress

Samantha’s decision to find a new home was partly shaped by these expectations of heteronormativity. Her move was precipitated by the ending of a long-term relationship. “We bought a house and were planning to move in together,” she said. “The breakup actually triggered my thought to move out –because I can’t see myself living off my parents for another decade, until I am ready to settle down again.

“It also made me relieved that we didn’t buy public housing, because then the breakup would be so much more complicated.”

The desire to stay in the ‘right’ kind of family is also powerfully felt in the sense of guilt that Samantha felt when she chose to rent a room in a shared apartment.

“It almost feels like you abandoned your family,” she said ruefully. “Asian values. But I guess I needed to prioritise myself.”

As institutions like marriage become less important in how we make meaning of our lives, the importance of what sociologist Anthony Giddens calls a “biographical narrative” comes to the forefront. Instead of defining our identities in accordance to our sense of belonging to particular social groups, the growth of the individual self becomes a story we can write, a project that we can cultivate.

Samantha’s relationship to herself became a key part of her life. “I’d say my relationship to myself becomes a work-in-progress. On the one hand, I enjoy the space to figure out who I am as a person – like I started attending more yoga classes, started spinning. I enjoy quiet time reading. But on the other hand, being alone most of the time also means I need to enjoy my own company. That’s something I’m still getting the hang of.”

An increasing demand for homes beyond the HDB marketplace has created new markets of co-living spaces, aimed at fostering new types of communities beyond the rubber-stamped nuclear family. Companies like Figment, Hmlet, Cove, and Commontown have all sprouted over the past few years, each offering stylish bedrooms with communal kitchens, lounges, work areas, and even organising social activities like yoga classes and meditation sessions.

While this iteration of co-living appeals to the moneyed millennial and the digital nomads, co-living spaces aren’t new. Intimate ties that contest the conventional family model has always been the province of the queer community, who have been finding ways to make life work even when it is difficult to attain full recognition in the eyes of society and the law.

READ: What Happens When Your Self-Identity is Tied to Your Partner

Creating chosen families

Studying lesbian and gay families in San Francisco in the 1980s, anthropologist Kath Weston observed that the language of love and solidarity was how queer families grounded kinship ties. Through holiday celebrations, shared pasts and offering help in crises, queer families bound together households out of sexual and non-sexual relationships, including children, friends, and lovers in flexible and dynamic family formations.

For Raksha Mahtani – who founded an active Facebook group explicitly geared towards finding and offering accommodation for the queer and trans community in Singapore – Weston’s findings partly echoed her experiences, too. “I heard stories from older lesbians opening their houses to queer houseless friends who crashed on their couches,” she said. “I’ve also lived with wonderful and nourishing queer and trans folks.”

The Queer/Trans Housing Singapore group has seen its members rise to the occasion when housing needs became apparent, stepping in where blood kin cannot or will not. “During circuit breaker, someone was kicked out by their landlord and needed a place on urgent notice. Another person reached out independently and linked them up with a temporary shelter. People respond to each other’s needs, and the more that happens, the braver people feel about being vulnerable and sharing these needs.

“A few people have shared that they felt so much more at peace. That safe space is a place where your body is not misgendered or misjudged, where one can just be, and be okay with taking up space.”

All of this takes necessarily place out of the HDB sale/purchase market and in the rental world, which has its own set of vulnerabilities – such as landlords refusing to rent to lesbian, gay, transgender, intersex and questioning (LGBTIQ) folks or choosing to evict renters on the basis of their sexuality.

In addition, Raksha added that queer youths who have been outed against their will have faced homelessness after being kicked out of their natal homes. Others might grapple with psychological, physical and/or sexual violence from their natal families, and might not have the time or resources to plan a secure departure and find appropriate external housing. These observations are supported by research conducted by organisations like Sayoni.

“Singapore’s housing policies are so intertwined with how the state designs families to look like,” Raksha said. “Because they cannot buy flats before 35, they have to pay rent for longer than married heterosexual couples.”

The cost of an ideal family model

Waiting to turn 35 before qualifying to purchase a HDB under the Single Singapore Citizen Scheme is, for some, just too long. As Kerrie Wee, who recently bought a private apartment with her long-term girlfriend, said, “There’s no real choice given to us – it’s whether you rent, which is dead money, wait till you’re 35, by which you would already have lived one third of your life, or purchase a private property.”

But the decision to purchase your own home comes with its costs, which can be astronomical. “We would not have any grants or subsidies, so price was definitely a huge factor,” Kerrie explained. “I can understand that it would be hard to allow LGBTQ people to purchase HDB flats, because that would mean that they have to accept that there are such people in Singapore, but I do wish there was more support in purchasing our first home.”

Samantha summarised these issues succinctly when she acknowledged that “everyone knows our housing policy rewards heterosexual couples that fulfil the government’s ideal of a family.” Queer people are penalised, of course, but so are migrant women, single parents, and people who simply are not interested in the norms of marriage and children.

People right now make do by working around HDB’s policies but at some point, making do can no longer be enough. To rethink what makes a house a home is to make room for an expansion of possibilities that accommodates a range of family formations and communities bound together by mutual support and love, rather than solely by blood or by marriage.

It is, after all, as HDB itself said, our home.

References

Chua, B. H. (1997). Political legitimacy and housing: Stakeholding in Singapore. Routledge.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Polity Press.

Heng, G., & Devan, J. (1995). State fatherhood: The politics of nationalism, sexuality, and race in Singapore. In A. Ong & M. G. Peletz (Eds.), Bewitching Women, Pious Men: Gender and Body Politics in Southeast Asia (pp. 195–215). University of California Press.

Oswin, N. (2010). The modern model family at home in Singapore: A queer geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 35(2), 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00379.x

Weston, K. (1991). Families We Choose: Lesbians, Gays, Kinship. Columbia University Press.

Join the conversations on THG’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.