Speaker of Parliament Tan Chuan-Jin sharing his favourite hobby of ‘Iron and Chill’. (Photo source: Tan Chuan-Jin/Twitter)Speaker of the House and People’s Action Party’s (PAP) Member of Parliament (MP) Tan Chuan-Jin, de-stresses by ironing while watching his favourite shows on TV.

In her declaration of what the Singaporean core means, central executive member of the Progress Singapore Party (PSP) Jess Chua, 37, likened Singaporeans to the chicken and the rice in Singapore’s national dish, and foreign workers here to the chili “that is not the essence”.

On Saturday, 14 August, Minister for Home Affairs and Law K Shanmugam posted a video of himself carrying weights that were gradually increased to 1.5 times his own body weight. The post garnered 10,000 likes, 940 comments and 849 shares in just 21 hours.

In a TikTok video to publicise its fund-raising Christmas concert last year (2020), two young women from PSP were seen holding toy animals and dancing behind Dr Tan Cheng Bock, the party’s chairman.

If certain analogies will not be used in Parliament as an argument, or if some content may create questionable public images, how then should politicians navigate the wild, wild world of social media to keep their behaviour and etiquette in check?

How have politicians in Singapore “weaponised” social media as a political tool?

The ability to control one’s narrative and be the master of a personal digital mouthpiece makes social media an attractive political tool and with the power shifting back to politicians, reducing the dependence on mainstream media to carry important messages, these public figures can easily reach the population, their intended audience, at a click of the mouse or a tap of the finger.

But the strategy to penetrate the masses here is another ball game altogether – because essentially digital behaviour can build or break a politician’s credibility and career.

A case in point is former President of the United States Donald Trump. He spread his message of “making America great again” through social media, especially on Twitter, and this turned him from a billionaire businessman to the 45th US President.

Since then, he used Twitter to share his unfiltered thoughts and eventually his favourite megaphone turned on him and he lost his presidency.

Associate Professor Eugene Tan, a lecturer of Law at Singapore Management University (SMU), says: “Generally, Singapore politicians have sought to have a meaningful social media presence. At its core, [social media] is a political tool that enables politicians to be connected all the time [because] people read their posts anytime [and] anywhere.”

Some of the politicians, whom Assoc Prof Tan says have capitalised on the inherent power of social media, include Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, Leader of the Opposition Pritam Singh, and Dr Tan.

“These politicians use Facebook [effectively] by emoting well, sharing their perspectives on issues, and explaining the party’s, [the] government’s or their own positions,” he says.

Assoc Prof Tan feels the “good use of photos and images and [the] attempt to include photos of people they meet and events they were at” helps them connect with their target audience.

Dr Natalie Pang, a senior lecturer for Communications and New Media at the National University of Singapore (NUS), shares the same views. “Politicians using different social media platforms to share their work, gather inputs and concerns, as well as offer a platform (beyond the usual Meet the People session) for citizens to approach and speak to them…is useful in terms of engaging citizens,” she says.

Ms Gwyneth Thong, a 23-year-old postgraduate student in Psychology, also feels that politicians have effectively leveraged social media as an extended political tool. “Some have even left a lasting memory after exploding into the limelight online, [and ] have successfully incorporated [social media]as a key means of public communication,” she shares.

Others on the other hand see the strategic politicising of social media as a ‘political tool’.

Secretary-general of the Reform Party (RP) Kenneth Jeyaretnam, believes that the “mainstream media is state owned and managed” so social media can be a platform to “hold [the Government] accountable”.

He says it is because there is no “freedom of expression and therefore no means to transparency and accountability and [the government] needs to be challenged” through social media.

Mr Jeyaretnam also recognises that social media is a double-edged sword because while it is accessible to the public, the ruling party can also monitor it.

Sarah J, who has declined to use her full name, is cautious about putting her opinions online as well.

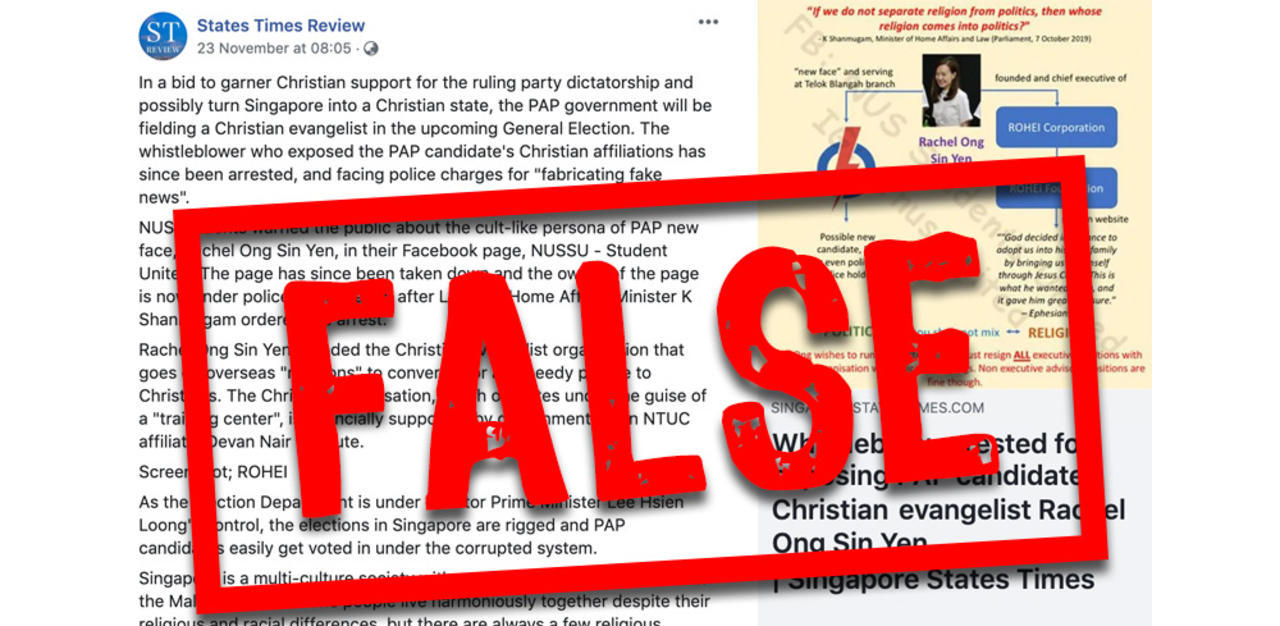

She cites the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) as an example and says the authorities must understand that connecting with the public on “surface issues” virtually is different from connecting with them at a personal level to understand the real issues at hand.

Not everyone will share their concerns or issues in the comments section, knowing that politicians may not read them, she says. However, when politicians are on the ground, there is a direct conversation that can take place with residents and the issue on hand can be explained better then.

Mr Jeyaretnam also feels unless there is real engagement to communicate their manifestos, “slick videos and viral memes [are] just vanity projects”.

He also warns against the weaponisation of social media to sideline democracy, especially when there are those who are “in digital poverty [or with] some disabilities [which] make [social media] difficult for them to access”.

Martin Piper, a PSP member, believes some politicians use it to gauge popularity and success, although they may be misled. “Some do have large numbers of followers on Facebook but the number of followers does not always equate to electoral success,” the 47-year-old technology manager shares.

He questions how success is measured in terms of whether the politicians won their end games.

“Success is hard to gauge because it depends on how success is measured,” Mr Piper starts.

He uses ex-President of the United States, Donald Trump, as an example.

“[Trump] had lots of followers but when you look at his messaging and the quality of engagement with them, it was quite clear that it actually did a lot more harm to the political ambitions of the Republicans — he lost the election, was impeached twice, and was a one-term President,” Mr Piper says.

If using shock tactic is one of the purposes politicians hog social media, he feels it goes against successful political messaging which should be “truthful, helpful, and affirmative” and not “contentious”.

Top ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ for politicians

When it comes to getting to know your leaders, Dr Pang says: “Citizens want authenticity.” and politicians using social media should offer just that to their target audience, telling the public about their own “values, beliefs and attitudes”; and this is shared by many TheHomeGround Asia spoke to.

Mr Charles Yeo, chairman of RP, agrees. He says that “the most important [thing] to do is to be genuine and [not] be fake”.

“As people are more intelligent than [many] politicians think they are. They can sense fake answers,” he continues.

Assoc Prof Tan explains that it is important to be “genuine and yourself” as “social media is an extension of [the politicians’] real world persona” and therefore they should not “pretend to be someone else [and be] inconsistent between the virtual and real worlds”.

Like Assoc Prof Tan, Mr Piper believes that being “honest, truthful [and] consistent” is part of authenticity and says the cost of being fake is breaking trust with social media users which has taken “ages to build but can be wrecked in a very short amount of time”.

Another point that politicians must be mindful of is the factuality of the things they post.

Ms Thong says she values posts that are “[backed] up [by] evidence”, as it will prevent the spread of misinformation.

“Jamus Lim is one example of a politician who does this frequently on his Instagram posts, [referencing] studies and statistics to support his arguments,” Ms Thong says. Mr Lim is a Member of Parliament (MP) from the Workers’ Party.

Dr Pang says that politicians like Mr Lim should not take statistics at face value and should “check sources of links, posts and pages that they intend to share”.

She says although it is not entirely about factual inaccuracies all the time, some contents can be offensive, “exacerbating and inflaming online discourse on important topics” within the social media domain. Positivity and respect seemed to be another important etiquette that politicians should be mindful about’.

Childcare teacher Josephine Ho, 37, says politicians should “speak positively and have good words to others on social media”. She adds that they must be “considerate” towards others too. At the same time, Ms Thong asserts that politicians should refrain from making personal attacks, such as the recent ‘snowflake’ debacle, as it is one of the fastest ways of losing supporters.

The ‘snowflake’ controversy came about in a Facebook post by former PAP MP Amrin Amin, where he warned people not to misconstrue every error as a “racist” one. However, when a netizen commented that some do still perceive it as racism, Mr Amin called the user a ‘snowflake’ for taking offence too easily.

Mr Piper echoes this etiquette, saying there is a need to “build a platform and use it to help positive change in society, [and] don’t use [it] to cause negative changes”.

But above all that, politicians should not just be “narcissistic” and work hard at being “all things to everyone [and] attempt to be a social influencer”.

“Get out and walk the ground!” Assoc Prof Tan says.

Like Assoc Prof Tan, Sarah also wants politicians to pull away from their screens and “engage the ground directly”. She feels they should not use social media as an excuse or convenience to “address needs” but not having “a feel of real issues”.

Managing trolls online is also tricky for politicians.

Mr Jeyaretnam stands firm on “[outsmarting] the IB” or internet brigade, a group of people who “may or may not be government sanctioned and are perceived to defend the establishmentarian agenda and/or attack the opposition” on the different digital platforms.

Mr Piper also asserts that politicians should not let “people hijack the social media platform”.

“For example, if someone is using public comments to be negative or spread falsehoods, then [the politician] needs to actively remove the comments and use the block feature,” he advises.

Dr Pang agrees and says that “while it is important to correct falsehoods and inaccuracies” one should not be“baited by the trolls”. “But do not be afraid to engage followers in the comments,” she adds.

The wrestle between personableness and status

The public seems to enjoy going on social media to engage politicians who seem ‘unreachable’ in real life. This is where the platform serves to bridge the perceived gap.

To Mr Piper, integrity is a sign of dignity and not so much the type of pictures or videos shared. “Being truthful and demonstrating integrity is being dignified,” he says, adding that the way to attain it is “being the same person in public without trying to cultivate a separate public persona”.

Assoc Prof Tan agrees, saying, “There should be no difference in how they relate to people in person and virtually [engaging the people] … When the online persona is a true, uncontrived expression of who one is, [it] will enable a loyal following to develop”.

Ms Thong supports this, saying that politicians need to be authentic and ‘vulnerable’ online. “In fact, it seems that when politicians share their vulnerabilities or personal reflections online, they tend to receive more engagement and even a boost to their legitimacy (when done well),” she says.

“In my opinion, a genuine connection with the people over time will foster respect and status that comes later. And although politicians are expected to maintain standards of decorum, nothing is stopping them from ‘being themselves’ online,” Ms Thong adds.

Dr Pang, on the other hand, says that the purpose of the political tool is very much dependent on the “aspirations that the electorate has in the politicians”.

“When Donald Trump won the US Presidential Election in 2016, one thing that was clear to me was that it demonstrated that the American electorate was disillusioned with the status quo associated with candidates that looked and behaved in ‘presidential’ ways,” she says, adding that Trump was “every man’s answer”.

Dr Pang draws the distinction between Westerners and Singaporeans, and says that social media users’ tastes and expectations in politicians are not static.

“Singapore is not America, of course. But the attributes that people want in politicians can change. I think that people [here] still want their politicians to behave in a dignified manner while being approachable and relatable [at the same time],” she remarks.

In order to tread the thin line between personableness and status, Assoc Prof Tan says politicians can use social media as “avenues for them to share some personal thoughts on matters of public concern as well as the mundane”.

“One can look at social media as an open diary where politicians share thoughts and highlight activities. The warmth and character of their personalities must come through [here],” he advises.

As a social media user, Ms Thong also affirms that content which shows “snippets of their daily activities that most people do” can help netizens respect politicians while seeing them in a different light.

“For example, MP Baey Yam Keng often posts pictures of himself running. It adds dimension to his online persona and can be used to spark interaction with his followers,” she says.

Another way that helps Ms Thong to connect with politicians is through their stories. She explains that “people naturally prefer stories over statistics, and a good post links a compelling narrative to a meaningful initiative”.

Citing Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat as an example, she says he recently shared a personal story of when he was a police officer, to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Singapore Police Force. “Based on the [number of] comments alone, his post garnered twice as much engagement as usual,” Ms Thong says.

However, Dr Pang says a pitfall that should be avoided in the quest to connect with the public is “to be baited into uncivil exchanges with trolls or engage in identity politics”.

The political posture in public interaction

This, Dr Pang says, will tarnish the image and credibility of politicians.

Instead, she says “politicians could use [public’s] comments to address [their] genuine concerns and questions [as] responding gives one the opportunity to also connect in person”.

Mr Yeo agrees. He says“it will assist them to build rapport with the young [voters]” and he himself does so “a great deal”.

Assoc Prof Tan says it ultimately boils down to the politicians’ “judgment call”.

“Social media is not really an appropriate platform to get into an extensive discourse and [highly] charged debates on issues of the day. Elected politicians are not elected to be keyboard warriors even though social media is an engagement tool,” he remarks.

Dr Pang agrees and comments that while it is “important to correct falsehoods and accusations in a dignified and objective manner”, she says that politicians should not be “glued to social media all the time”.

In addition to why politicians should avoid excessive engagement, Mr Piper states that there is definitely “real danger” in misinformation. So in order to engage with comments well, politicians must be “well-informed” because if “someone [spreads] false and incorrect information, it could [even] lead to someone getting sick and dying”.

“Reliable sources come from [experts’] opinions, and then using rational and analytical thought to filter out what is actually the truth is [acting] with integrity,” he adds.

Mr Piper believes that it is a “distinct lack of integrity to just go along with conspiracy just because it’s popular on social media and potentially gains votes”.

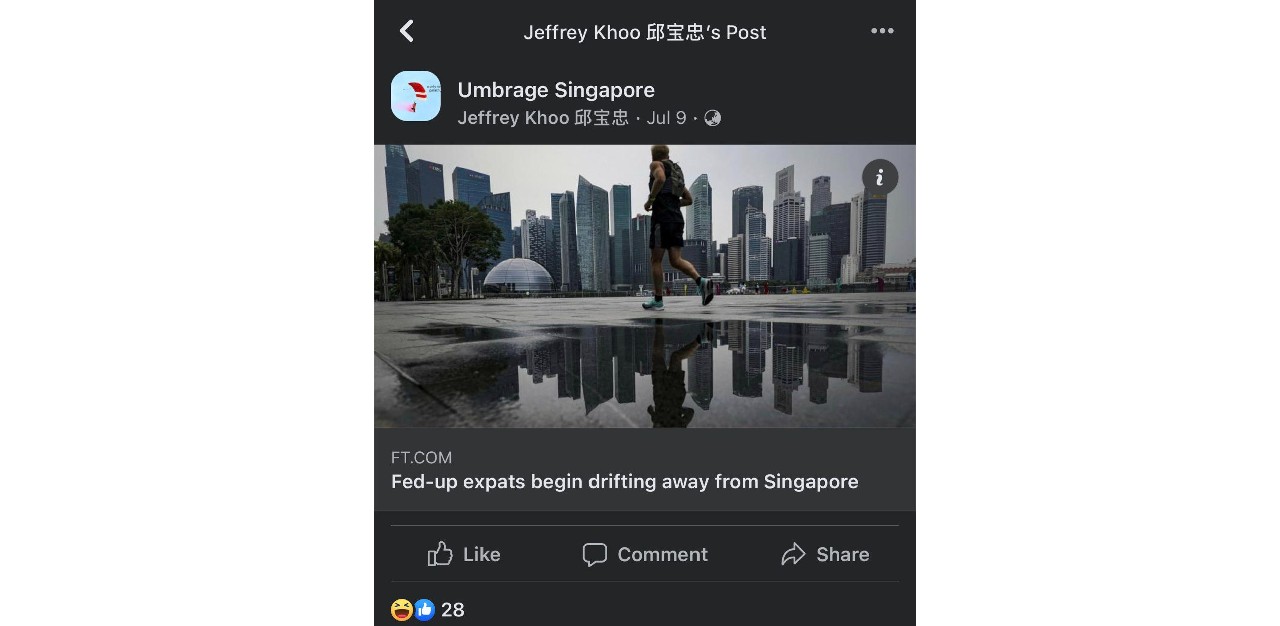

As for public netizen groups, such as Umbrage Singapore or Critical Spectator, the experts feel that politicians should not even venture in.

“Some of [these groups] do not bring much value at all, variously they seem to conflate being contentious and sharing conspiracy nonsense with popularity, which isn’t right at all,” Mr Piper comments.

In his view, the “quality of public discourse [must be] raised” otherwise it is useless and purposeless in doing so.

The key question is: “Is there a real need to do so?” Assoc Prof Tan asks.

He cautions that politicians would have “to be careful wading into public groups” because they will have to face the responses of the netizens which they “have little control over”.

Ms Thong agrees: “The politician must be prepared for a public critique of themselves – and their affiliations – whenever they take a stand on an issue. This logic stands regardless of the politician or public group’s alignment on the political spectrum.”

If things posted are false and controversial, they should “not be free from consequences” and “POFMA is tangentially related to this, [and] suffice to say that the law should be applied equally to all, including politicians themselves”, she says.

If used perspicaciously, social media could be politicians’ most powerful weapon but when used in bad faith, however, it could be a lightning rod that destroys a politician’s career at the speed of light.

A healthier way is perhaps “[delegating] the social media management work to assistants or team members, similar to what celebrities do [although] all comments should be carefully reviewed before posting to [prevent] bad [publicity]”.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.