In the first of TheHomeGround Asia’s three-part series on sustainable living, Singaporean youths discussed how they navigate the daily conundrums of battling climate change with little green steps.

But what about taking one giant green step instead?

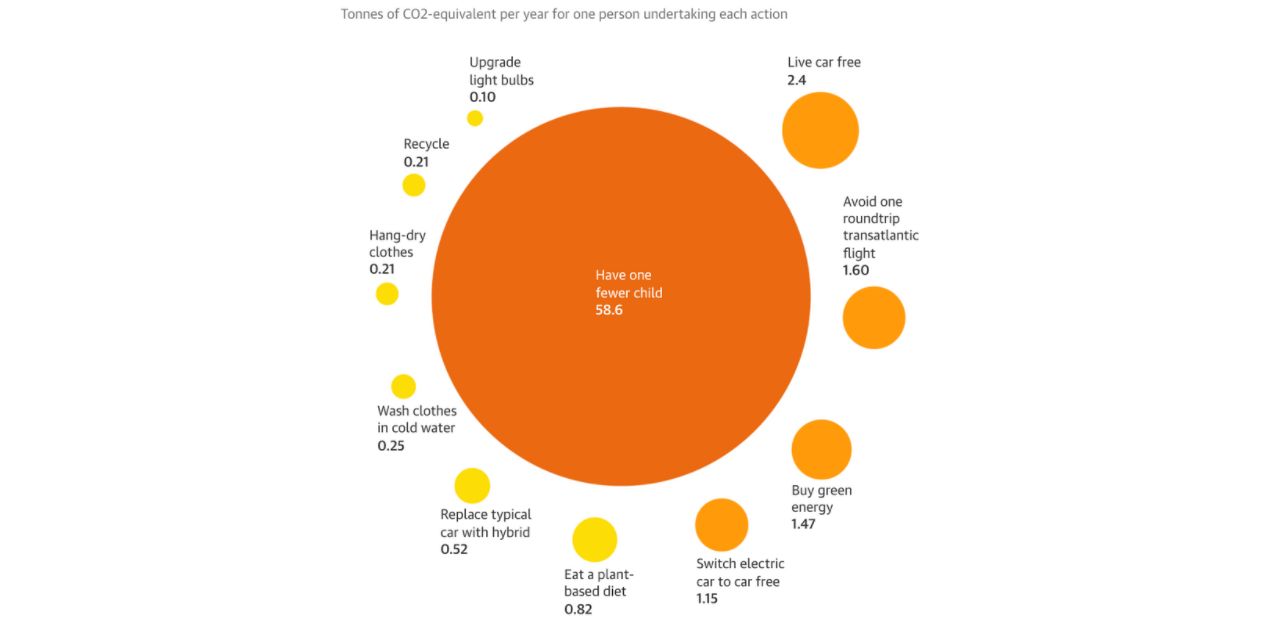

In July 2017, a Guardian article proclaimed having one less child to be the single most effective way for people to reduce their personal carbon footprints.

Experts calculated that each child contributes 58.6 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) for a year of a parent’s life. To put this in perspective, that is equivalent to abstaining from 36.6 roundtrip transatlantic flights a year, or 71 people turning to plant-based diet.

Having a child is a deeply personal decision, and quantifying the value of a child’s life — or the experience of parenthood —in terms of tonnes of carbon can be reductive and even offensive to many. Numbers aside, this movement is being driven by strong undercurrents of eco-anxiety and projected guilt for bringing a child into a world with a future so uncertain.

“There is a growing acknowledgement that the likely societal impacts of future climate disruption have been a factor in not having children,” says Associate Professor Winston Chow from the Singapore Management University (SMU).

Some reasons for this include the ethical views of “I don’t think bringing in one more child to the world is a sound one”, and the question “is it fair to give my child such an uncertain future?”, given the dwelling state of the planet, Professor Chow adds.

‘In an ideal world, we’d still like to have kids’

The sentiment is gaining traction among young couples in Singapore, according to a Straits Times report.

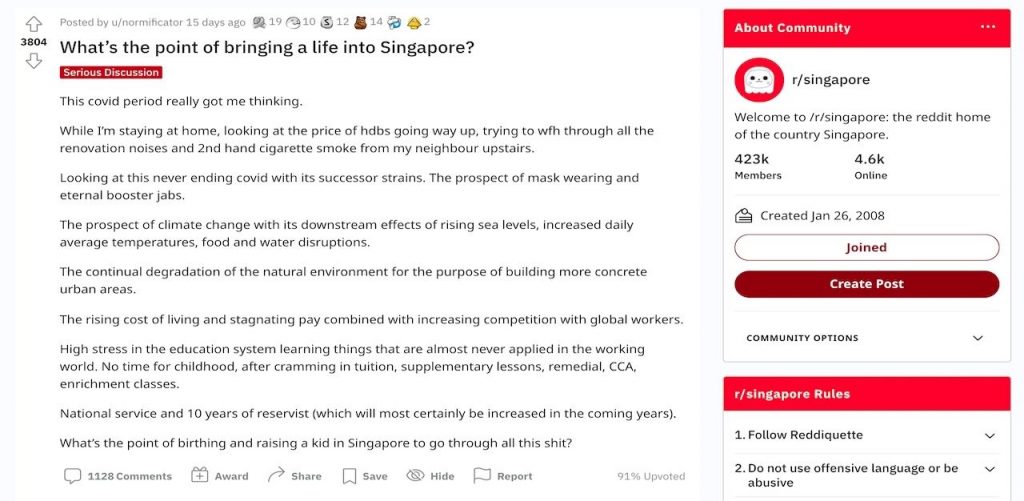

Professor Chow says the ethical factor is on top of “grounded economic issues, such as economic cost of raising children elsewhere”, among many others — as seen in this viral Reddit thread below.

But contrary to popular belief, this group of youths do not merely constitute people who “never felt a calling to have [their own children], or do not “have an intrinsic love for children”, as the article highlights.

Ms Tricia Tan, 23, is just one such individual. She had always envisioned having a large family with many children since she was young. “I like kids. I like seeing them grow, and seeing them learn,” she says. “I can understand why it’s a very fulfilling thing to be a parent. It’s a very unique experience.”

Yet, in the course of pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Environmental Studies, Ms Tan’s stance took a 180-degree turn.

“After you learn more about the extent of environmental degradation, then having kids becomes a very complex issue,” she says. “It isn’t just about you anymore, it’s about the kids and their feelings too.”

“There’s no promise that they’ll be able to live a long, safe, and fulfilling life on Earth,” she says, emphasising that no one can actually consent to being born. “There’s a very real possibility that they don’t get to see a lot of things that brought us joy, with oceans rising, animals going extinct, and forests being burned down. What kind of world would they have to grow up in?”

Dr Matthew Schneider-Mayerson, an associate professor of environmental studies at Yale-NUS College, points out an additional reason why environmentalists in particular are choosing not to have children. “Raising children takes up time, money, and energy that could otherwise be used for environmental politics and other actions,” he says.

Generational differences in ideologies

Sociologist Paulin Straughan told The Straits Times that many young adults argue that they are marrying for intrinsic reasons. “The purpose of getting married is for self-fulfilment rather than extending your family or meeting your extended family’s expectations,” she says.

Within the cultural context of Asian families, however, the decision to have children traditionally involved grandparents and even extended family members. The advent of a new environmental consideration might, then, threaten the intergenerational social fabric.

Agreeing, Ms Tan points out that the older generation “had a much better excuse than us [to not grasp the gravity of having children], because they honestly didn’t know any better”.

“A great many inventions came out of the different revolutions over history to give us the high quality of life that we have today. So, it’s understandable why they were caught up with other issues without thinking of the long term consequences of having children,” she says.

Furthermore, environmental results are highly intangible and take decades to manifest. Newer generations grapple with eco-anxiety at a level often incomprehensible to their predecessors.

“We feel much more morally obliged because we can feel the direct impacts of climate change now,” she adds.

Paradigm shift in policy required

With one of the lowest birth rates in the world among developing economies, some might say that Singapore, as a nation, may not have the luxury to put environmental concerns before economic ones.

Since the 1980s, the Singapore government has implemented a relentless string of pro-natal policies in a long-drawn and desperate attempt to counter the country’s ageing population issues.

They have yet to comment on how climate-related antinatalism fits into the larger scheme of policymaking. Does having fewer children mean that our economy and healthcare infrastructures take a hit?

Environmental educator Tan Hang Chong believes that a paradigm shift in this aspect is both possible and necessary. “To challenge this paradigm, we need to challenge the assumption that as people get older, they become economically inactive or reliant on their children for support,” he says.

According to him, a big part of the solution lies in promoting active retirement, so that people can be less reliant on their children. This counters the notion that one needs to have children to take care of them in old age in order to retire blissfully.

There should also be greater efforts in reskilling senior citizens so that people can remain economically active in the workforce if they want to, he says.

In anticipation of the Silver Tsunami — the influx of infrastructural issues related to an ageing population — Mr Tan also highlights the importance of preventive healthcare to counteract the inadvertent rise of chronic illnesses.

“It is great that people are actually living longer lives. But are they living longer quality lives?” he asks.

Professor of Social Sciences (Environmental Studies) Michael Maniates from Yale-NUS College writes in his book, Consumption Corridors: Living a Good Life within Sustainable Limits, that rather than “frightening policymakers into action, […] limiting levels of consumption doesn’t need to be a dreary dystopian thing”.

“It can be exciting for us to think about reducing consumption in ways that lead to greater prosperity, peace, freedom, and opportunities to fully realise our humanity,” he says.

Redefining parenthood

Mr Tan, 41, has also personally decided against having children, despite loving to educate the young . But he does not feel a sense of loss over not having his own biological child and believes he derives the same fulfilment from taking care of his three nieces. After all, it takes a village to raise a child.

“I’d like to think of myself as a pseudo-parent or co-parent. It can be just as fulfilling a family life because we have shared responsibilities,” he says.

“What I’m concerned with is not my own biological heritage, but my cultural legacy — to know that the work I’ve done leaves an impact on future generations,” he adds. “Therefore, there is no need for me to distinguish whether or not a child is biologically my own.”

He points out that fostering children from marginalised communities, adoption, and even opting instead to raise fur kids are options that young couples can, and are, increasingly considering.

Children can be, and still are, the hope for the future

Ms Tan highlights the importance of not antagonising any one group of people for a decision so personal. Instead, she believes in taking a neutral stance and finding the common ground between opposing viewpoints.

“I think something that both groups have in common is that they value the lives of children. By choosing to have less, we are doing the same thing, because too many children might result in each child having a slightly lower chance of being able to reach their full potential, because there’s just not enough resources on this earth,” she says.

Even so, there remains a strong group of voices, environmentalists included, who still pin their hopes on parenthood and children, as TheHomeGround Asia writer Chester Tan surmises in a recent opinion piece.

And that’s completely justifiable too.

“I found two climate-related reasons why environmentalists are choosing to have children: as a means of remaining personally invested in the future of the planet, and because of the hope or expectation that their children will become environmentalists,” Dr Scneider-Mayerson explains in his article, The environmental politics of reproductive choices in the age of climate change.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.