A corner of my bedroom no longer looks like my own. Strategically facing a window without much of a view lies a desk, a laptop, a monitor as a second screen, and an ergonomic chair – most of which are new additions to my restful abode within the past eight months. The chair is the latest one; a desperate purchase after developing back pain from sitting on an aesthetically pleasing yet poorly designed IKEA chair for the first few months of WFH.

From the hours of nine to six daily (plus-minus, but more pluses than minuses), I am confined to the corner I’ve built for myself — a deliberate demarcation of an office area; an invisible boundary forged in an attempt to contain the worklife I have willfully brought into my personal space. But as I lay in bed at 11 p.m., my mobile phone lights up with a work-related message, and I realise that what I have been trying to contain is already spilling over; the invisible lines no match for the demands of work that seem to know no boundaries.

A call for the Right to Disconnect

The negative effects of work seeping into our private lives have been widely documented and terms coined copiously: COVID brain, work-from-home burnout, Zoom fatigue – just to name a few.

Even before pandemic-related expressions sprouted up, work demands that infringed on employees’ personal time were a huge concern — so much that the French called upon a right to disconnect. Named the ‘El Khomri Law’ after the nation’s labour minister at the time, the law rolled out in 2017 mandated that companies with more than 50 workers must allow employees to unplug from work responsibilities outside office hours.

More countries followed suit with their own implementation or consideration of the Right to Disconnect. In 2018, Spain adopted their own Data Protection and Digital Rights Act that gave employees the right to distance themselves from work-related tasks during rest days and holidays, while New York proposed a bill citing a ban on responses sent through electronic work communications – whether via email, text, or otherwise – after work hours. For private companies with more than 10 employees, flouting this rule could result in a fine of at least $250 for noncompliance.

Singapore too has gingerly broached the topic in October 2020 when Radin Mas MP Melvin Yong urged for the Right to Disconnect legislation to be passed, which will allow negotiations between employer and employee on work responses beyond designated office hours.

Work and rest: the blurred lines

The proposed law seems to be what’s needed for the current generation of workers like Phoebe Chong. A thirty-something who works in the creative field, she shares that since the pandemic started, there has been no real break from work.

In addition, since no longer under the watchful eye of employers in the office, it seems the blurred lines between work and rest has dissolved entirely. “Since WFH started, there were measures put in place by management to ensure we weren’t slacking off, which felt quite suffocating.”

She adds: “Looking at people sending out emails at 11 p.m. or past midnight, makes you feel compelled to also do the same; to also provide answers whenever possible.” When pressed on this need to respond, Phoebe shared that there is a sense that she would get marked as someone who’s not a team player if she’s seen as the only one not replying in a team chat after certain hours.

“Read receipts, especially, tend to drive that culture because if you are seen to be online, then you should be able to reply, or at least, that seems to be the mentality behind it.”

The consequence is feeling like you’re stuck in a neverending loop — not having a sense of completion when work is done and having a sense of dread in awaiting new tasks that will crop up. This leads to physical and mental exhaustion that takes a worrying toll. Phoebe recalls a time, pre-COVID, where work put so much strain on her body that when she finally took an extended break, she was sick for two months.

Despite taking ownership for the job she’s undertaken (“I chose this line of work so I can’t really complain about it.”), Phoebe can’t help but express envy towards employees whose work isn’t as digitalised as hers. She is referring to occupations where systems or machinery is on-site and therefore work cannot be done remotely. For such workers, they leave their work behind once they clock their hours.

Difficulty in disconnecting exacerbated by technology?

Her longing for work to remain outside the home seems reminiscent of a time when technology wasn’t as advanced — a time without push notifications on phones and easily accessible emails. Even as late as the 1990s, speedy replies were not considered the norm, and faxes were still the preferred way to send information. This form of communication, and the expectations that come with it, ensured work stayed within the confines of the workplace, rarely, if ever, to reach the sacred spaces of homes – or in my case, the bedroom.

For the parents of millennials who were late in experiencing the boom in email culture and wireless networks, their reality is strikingly different — bringing work home was not a norm. But commitment to work responsibilities, it appears, still take precedence.

For Mdm Sharina, 59, while empathetic towards her children’s plight in adapting to a changing work landscape, views work outside of office hours as “part of their responsibility”. The mother of four who has two daughters — a designer aged 27 and a creative director aged 34 — still living with her, says despairingly: “It’s their job. They have the responsibility to finish it, but yes, they work so hard.”

She also observed that the situation has exacerbated since the circuit breaker started (“It’s almost like they never stop doing work.”) but stops short at saying that the expectation to remain connected is fair since time spent with family is compromised.

Mdm Lina, mother to a 35-year-old manager in the engineering sector, agrees that there should be some form of worklife balance. “It’s difficult for me to make plans with my son because he is always working. Work is work, it’ll never end, but there must be time for family life too.”

Meanwhile 61-year-old Mdm Chong, Phoebe’s mother who regularly sees her working late into the night, believes it is fair for bosses to expect dedication and commitment from staff, especially when times are bad. However she adds a caveat that clear communication with staff is essential, such as not contacting them unless absolutely necessary or to indicate if the reply can wait till the next working day, to avoid sending the wrong message to employees. While it may be justified, she adds that “the real question is whether such expectations are sustainable”.

Business models and ways of working ripe for change

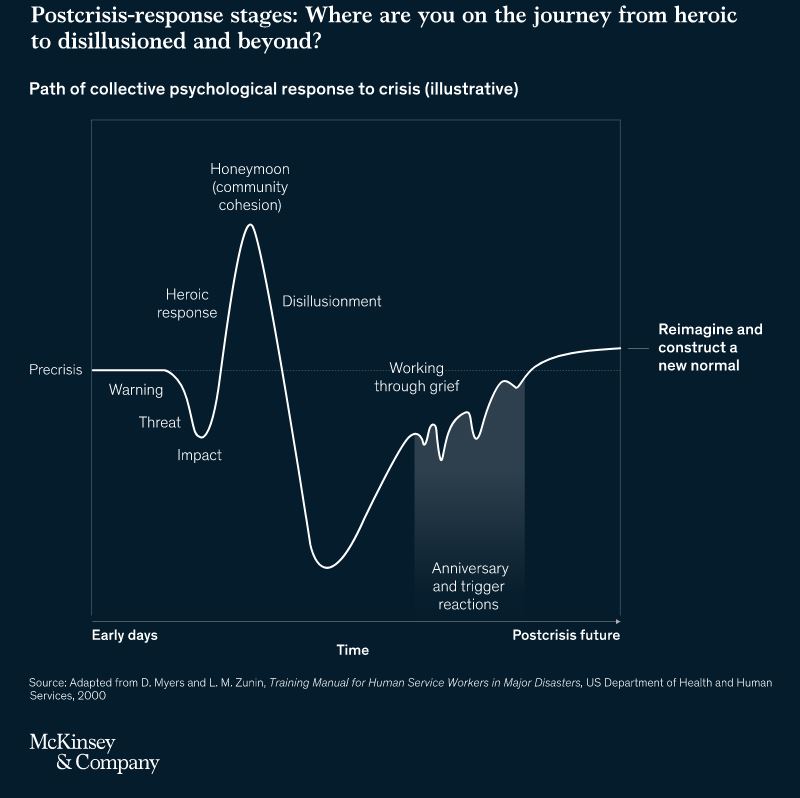

McKinsey & Company shares interesting insight into the unsustainable pace in which employees are expected to “sprint through what has become a marathon” since the start of the pandemic. While the initial novelty of working from home has shown that much can be done virtually on top of the perks of a now-obsolete daily commute, according to their postcrisis-response chart, employees will enter a phase of “potentially prolonged period of disillusionment, grief, and exhaustion” once the honeymoon period wears off and they are faced with months and months of a new norm that has no clear end in sight.

The solution offered is for companies to pivot to more flexible working models; to empower teams and strip down unnecessary bureaucracy. And seeing how unlikely it is for employees to simply bounce back to the way things were before the COVID-19 crisis, business models and ways of working are ripe for lasting changes.

For example, Mdm Chong shares an anecdote of her previous company which created a special arrangement for the creative staff (designers, production team) to begin work late and extend their hours accordingly. She says: “Many younger people nowadays seem to like the night time better for work, as long as their work quality does not suffer — in fact, it may even improve”. Having this option of flexible hours may ensure that employees are working at optimal times, thus maximising output, while maintaining downtime away from work.

Amy Lim, who formerly sits in upper management at a prestigious bank, proposes that leaders lead by example. “The way managers respond to their bosses outside working hours will create a ripple effect in the way employees respond to managers, i.e., if managers are quick to respond to their direct superiors, subordinates will tend to follow suit because it is perceived as what’s expected.”

She adds that there is also a time crunch in responding to text or emails especially if it means you will be disadvantaged. She shares an instance where a boss tosses a task to the team via email and a late response meant that decisions are made without an employee’s input. This may lead to decisions made that are not beneficial to the employee’s area of business.

It is clear that this work culture of perceived expectations greatly impacts staff behaviour and perpetuates the unsustainable compulsion to stay connected. HR consultant, Alice Tan, further cements the dire need for a shift in company culture that’s feasible for both employer and employee. An agreement that sets boundaries on what is considered urgent and when an employee is required to reply, she suggests, would allow employees to disconnect during agreed upon times without fear of negative repercussions or judgement.

She firmly adds: “In cases of overworked employees, employers should themselves look at what is feasible and not just expect their employees to fulfill all tasks just because they asked for it. We cannot have repeats of PMETs dying on the job, such as like in the case of the young executive in the banking industry who died from exhaustion. If your employee is always working late hours, then there needs to be a readjustment of KPIs.”

This chilling reminder is reason enough for companies to create a workplace culture that provides a window for negotiation on the right to disconnect, as well as one that’s human-centric — viewing people as valuable talents that have both exceptional resilience and natural human limitations; not as machine-churning resources that are always on standby. And as we are now witnessing during this pandemic, the cost of the alternative — poor mental wellbeing, disrupted family life, stunted personal growth — is already too high for the situation to stay the same.

Join the conversations on THG’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.