As a generation that has been subjected to all manner of criticisms — think lazy, disrespectful, overconfident, spoiled, snowflakes, strawberries, and now, cheugy — Millennials the world over have had it pretty rough.

Many have been told they don’t work hard enough by the generations before them, but also that they sometimes try too hard by the generation after them.

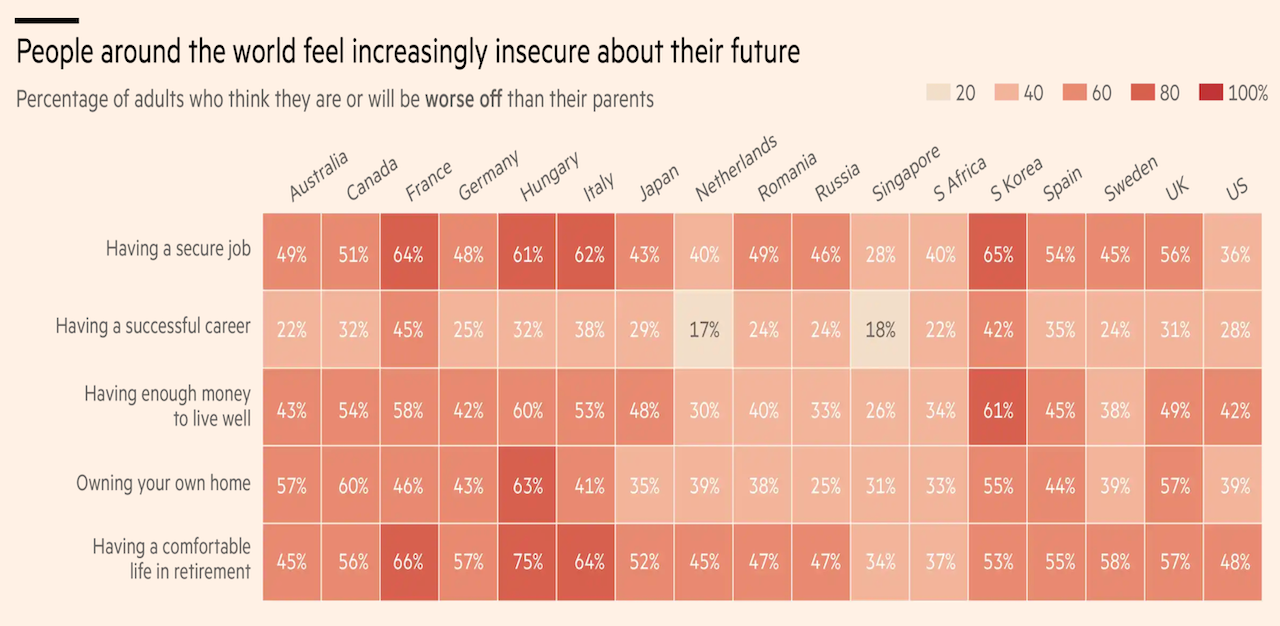

A Millennial myself, I often wonder if I have internalised these denunciations over the years. After all, we may be the first generation to make less money than our parents, on the average. Unlike the Boomers, most Millennials in the West cannot afford to own a house today, while over a third in Singapore do not feel secure about retirement.

Young, burnt out and anxious

Earlier this year, the Financial Times conducted a survey among its global readers to understand the major issues young people face today, relative to the prior generations. Thumbing through the findings was both reaffirming and consuming for me as thousands of young people around the world seemed to describe, with uncanny accuracy, the social immobility I have noticed in Singapore.

On many levels, it almost seems to us like the world is beyond repair, with problems compounded over generations and young people bearing the brunt of it. We were told that we would make it just like our parents and grandparents did if we work hard and have a good job, and that success is measured by having a house, car, family, children, and planned retirement. Then cost of living over the last five decades skyrocketed disproportionately to wages, and young people today across the developed world find themselves having to work two jobs just to pay rent for a small apartment, with no car or children, a partner who is as burnt out as they are, a massive student loan debt, and an unending supply of climate anxiety brought on by the actions of the previous generations.

In Singapore, where renting is uncommon, young people are stuck living with their parents until they get married. For some, it is even after they are married. Since people are marrying later, Singaporeans today are living under their parents’ roof much longer than their parents did.

Alas, the advantages the young people of today have over their parents and grandparents — higher salaries, better education and jobs, access to technology, diversified industries — have been cancelled out by the simple reality of intergenerational inflation. Making $100,000 a year helps no one when rent in the city costs half of monthly wages and one is $50,000 in debt because of the student loan.

What’s the point of having children?

Given this constant uphill battle for the good life, it is no wonder that fertility has declined across the globe, with more young people embracing a childfree life now than ever before.

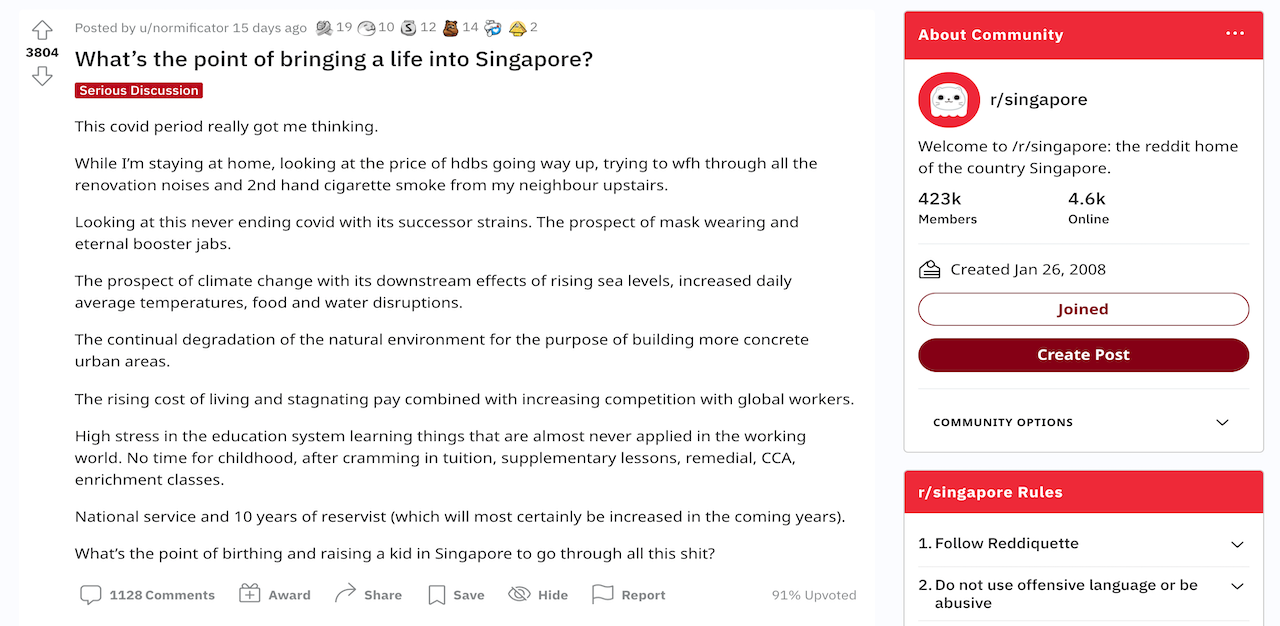

A recent post on Reddit’s Singapore community titled ‘What’s the point of bringing a life into Singapore’ had been upvoted over 3,800 times in less than two weeks, packed with a lively discussion of over a thousand comments mostly underscoring young people’s pessimism for Singaporean society and its future.

Other threads point to the same sentiment. Due to reasons that run the gamut from evolving lifestyles and impossible property prices to worrying inequality and racism, young Singaporeans, akin to their counterparts in the developed world, are making the conscious decision not to bring life into a world they view as increasingly problematic.

Echoing these sentiments, political science undergraduate from the National University of Singapore (NUS) Izni Azis describes her decision not to have children partly as a response to the current state of the planet.

“I’m not super well-versed in the environmental problems of our globe, but what I can gather is that the future seems very bleak,” she says. “I wouldn’t want to bring a child into this world knowing all of this, especially when taking other (societal) factors into consideration.”

It is evident that an uncertainty about the future contributes to the decision to remain childless. Much like the Financial Times survey had uncovered, young people are pessimistic when they look into the future. Ms Johanna Teo, a freelance creative in her late twenties, explains that apart from uncertainty, the need to bring more life into the world also seems unconvincing.

“There are enough orphans around,” she argues. “I would like to adopt if I do commit to being a parent”.

Here, Ms Izni shares an almost identical view. “There are already so many orphaned or compromised children out there who are alive and in need of care. I think adopting these children and giving them a home should also be a consideration for those eager to be parents,” she adds. “While I do not wish to procreate, I do support the notion of adopting or fostering children.”

Change starts at home

While the arguments are certainly cogent — I, too, would like to offer my children the opportunities they (and every other kid) deserve, and a world that may implode from climate disasters or a society that has lost its humanity to the rat race would make that improbable — I cannot help but wonder if this defeatist sentiment might, in actuality, be symptomatic of the very toxicity we young people claim to be against.

To put this in another way, could we have internalised all this talk of an unjust, deplorable world that we have taken its flaws as preordained principles, sealing the fates of our unborn children?

Society may be lost and the world has seen better days, but as individuals, it seems natural to feel powerless in the face of such overwhelming odds. And yet too many of us forget that this limit is often self-fulfilling, and that history is replete with change as a result of choices made at the individual level.

One of the first lessons I learned from my parents about change was when I was in secondary school. It was in the form of a Mother Theresa quote; ‘The way you help heal the world is you start with your own family’. The irony of this piece lies in this very idea — becoming a parent is everyone’s shot at changing the world.

Indeed, it is hard to imagine that the unborn generation would be anything like we are today. A would-be parent who disagrees with the workaholic culture in Singapore, for instance, needs only to inculcate in their children an appreciation of the difference between working to live and living to work, and the value of a life balanced by fulfilment and achievement.

In the same vein, there is no universal truth that warrants our perpetuation of the toxic ‘pressure cooker’ environment to which we currently subject children. A great example can perhaps be found in the approach Dr Teo You Yenn, the Singaporean sociologist and author of the national bestseller This Is What Inequality Looks Like, takes with her child — Dr Teo had shared on an episode of CNAs On The Record podcast in 2018 her conscious decision not to enrol her daughter in tuition and enrichment classes, “so that she doesn’t have more advantages than she already has”.

Such a parenting philosophy demonstrates not just a reluctance to perpetuate the inequality that resides within a meritocratic system that blindly advantages the privileged, but also the autonomy parents have in rewriting the narrative. Arguably, there exists no guiding principle in life that mandates that we all own a car, go on luxury vacations to Europe, or live in condominiums with pools and saunas. The concept of a good life cannot be monopolised.

Similarly, if we truly fear climate catastrophe, resent political subordination and detest social injustice, then we ought not to walk away from them but face them head-on. If we truly believe that society is fundamentally flawed, then there should be no greater source of empowerment than a commitment to nurturing the next generation. Conversely, leaving the game just means that the status quo will be maintained, naturally by those on the other side of the court.

Unenlightened socioeconomic policies may have beleaguered our generations, but the greatest opportunity lies in our recognition of it. Being a parent through birth or even adoption accords the next generation the chance to undo decades of wrong turns, and us the prerogative of seeing that through.

Chester Tan is a freelance writer, aspiring photojournalist, and communications student in his final year of university.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.