That smartphone in your hand.

It has increasingly become the personal assistant you reach out to for contact numbers, email addresses, information or even directions to get from point A to point B.

While using external devices to keep track of things makes our lives easier, Dr Oliver Hardt from the Department of Psychology at McGill College in Montreal said the constant use of external devices worsens our memories “if we stop using it like we are supposed to”.

Memory researcher Catherine Loveday conducted a survey in 2021 that found that 4 in 5 people felt their memories had worsened following the pandemic since many used social media to distract themselves from during the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdown, creating a greater reliance on smartphones.

Today, we use the calendar on our phones as reminders and take photos of important documents, allowing us to not use our memory, essentially outsourcing part of our memory to an external device.

While we were able to remember appointments, important birthdays, titles of songs playing on the radio and even contact numbers of family and friends, we now leave it all to our phones.

A case in point is when former journalist Jessinta Tan was 13, the current age of son Joshua Lee, she could “remember dozens of telephone numbers by heart and rattle them off from memory”. “Today, I only remember a handful, because I didn’t want the hassle of retrieving pieces of paper on which I had jotted down numbers, or having to flip a hardcopy address book just to find a number that I needed,” she tells TheHomeGround Asia.

“Joshua can remember two numbers for sure — his father’s and mother’s,” she adds. Joshua says he did not commit his friends’ mobile numbers to memory “because there exists a contact list stored in his iPhone”.

Like Ms Tan, sales and operations manager Maggie Chua says she, too, could remember a list of numbers, ranging from her home phone number to contact number of friends when she was 15 — the current age of daughter Amber Yam.

“Amber only remembers mine, her father’s and grandmother’s numbers but she cannot recall even her best friend’s,” Ms Chua says, adding that she can only remember her own best friend’s number “because we call each other every day”.

“I am no good at remembering new friends’ numbers,” she adds.

If we don’t use it, we lose it

The contact list is not the only convenience. The global positioning system or GPS is said to make people less geographically knowledgeable than they would be if they were using a traditional paper map.

As drivers here grow more and more dependent on navigation services like Waze, Apple or Google maps, the brain actually stops “doing the heavy lifting necessary to create and maintain mental maps”, turning drivers into what the Japanese call hōkō onchi, or “deaf to direction.”

Mr Aaron Toh, who drives for Gojek, says, “The GPS app is convenient because we don’t really have to think. The app will direct us to the destination and as drivers, we just concentrate on the safety of driving and getting customers there in one piece.”

And it is this “not thinking” that led a group of Japanese tourists going to North Stradbroke Island on the Queensland coast in 2012, to drive their rented Hyundai Getz into Moreton Bay. They were guided by their GPS which had forgotten to show there is a 14.5km stretch of water between the island and the mainland.

Such instances were what German psychologist Klaus Gramann was looking into. The results of his research, involving new ways of giving directions, were published in Frontiers in Psychology in 2017.

While there is no silver bullet for healthy ageing, medical experts agree that a key ingredient is keeping the brain active. Now if spatial navigation is an essential element to keeping mentally alert then the question should be why outsource this critical skill to our smartphones?

According to Dr Hardt, “the convenience has a price” and that price is the deterioration of your memory. He thinks it will get worse and “possibly lead to an increase in people with dementia”.

But neurologist Chong Yao Feng disagrees, calling “the risk of digital amnesia” an evolving topic. “There is much that is still unknown and it is premature and a tad simplistic to conclude that smartphones and computers will impair our cognitive functions”.

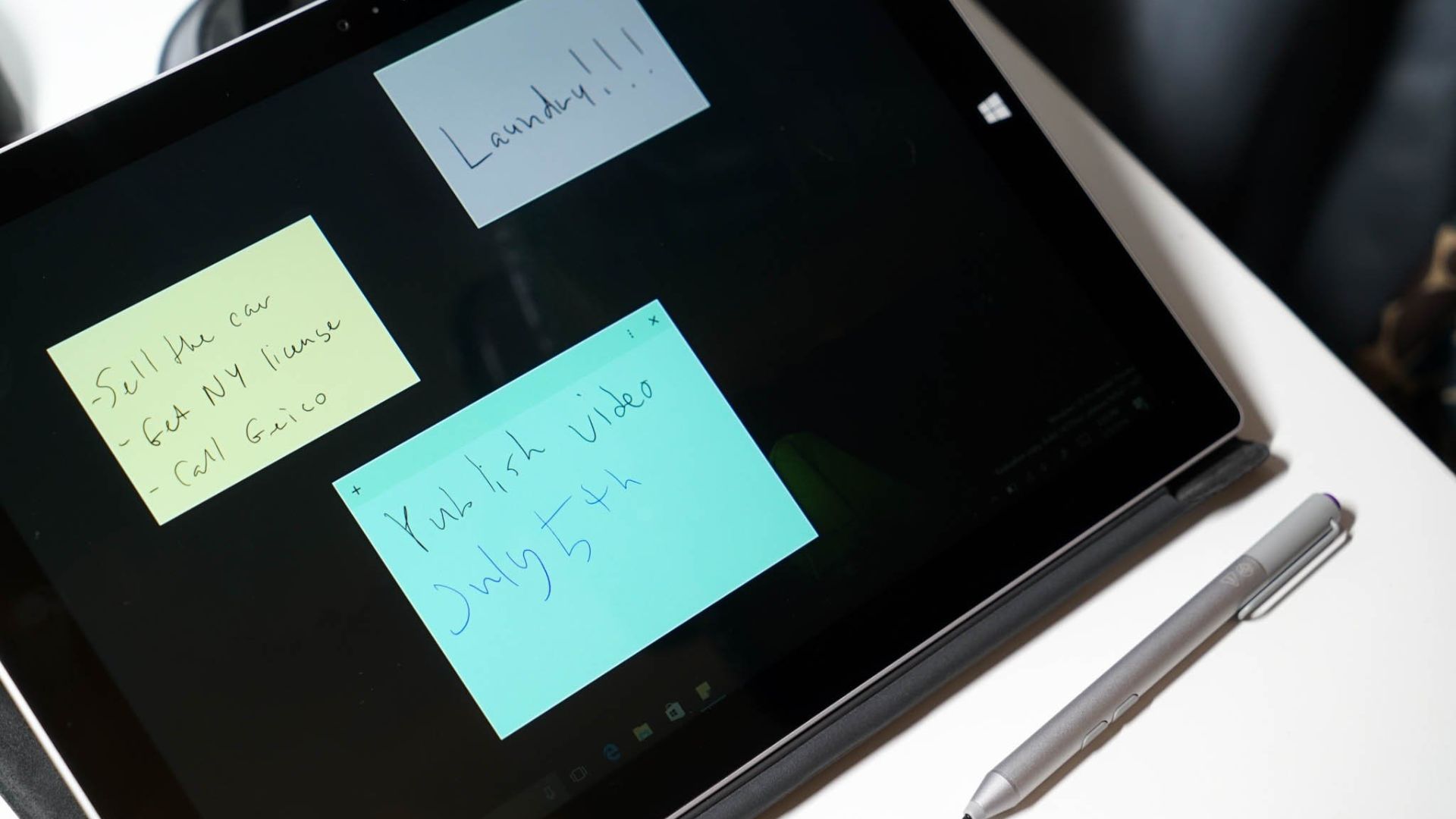

No different from using paper and post-it pads

Professor Chris Bird from the School of Psychology at the University of Sussex says, “We have always offloaded things into external devices, like writing down notes, and that’s enabled us to have more complex lives. I don’t have a problem with using external devices to augment our thought processes or memory processes. We’re doing it more, but that frees up time to concentrate, focus on and remember other things.”

Prof Bird, who runs research by the Episodic Memory Group, thinks we use our phones to remember the kind of things most humans find difficult to remember. According to him, we take a photo of the parking ticket so we know when it runs out, because it’s an arbitrary thing to remember. “Before we had devices, you would have to make quite an effort to remember the time you needed to be back at your car,” he told The Guardian.

“If we were to say that by ‘outsourcing’ memory work to devices, we are making our brains lazy, then often we ‘outsource’ memories by recording and writing down on notebooks. How different are those from relying or offloading to smartphones and computers?” asks Dr Chong, an associate consultant with the Division of Neurology at the Department of Medicine in the National University Hospital (NUH).

Concerns about “digital amnesia”, or the potential of smartphone habits wrecking the “cache” of your brain are only the latest in a long history of concerns over the impact of “new technologies”.

The ancient Greek philosophers worried that the development of writing would render people less likely to “exercise memory”. Similarly, concerns were raised when German Johannes Gutenberg developed the printing press.

“Despite these concerns, we are, today, taking both writing and the printed word for granted, and recognise how instrumental they are to the recording and dissemination of knowledge,” Dr Chong says.

He adds, “It is probable that, a century or two hence, future historians of the 21st century will be dissecting the effects of the use of computers and smartphones on humanity, and will debate about whether it had been a boon or bane overall. But what I think they will agree on is that these digital technologies would have become an inextricable part of their lives, in the same way as we do not question the existence or utility of writing or books in the year 2022.”

“Whether it has a net positive or net negative impact on our lives is likely to depend on how we harness the technology, the context in which we use it, and how we use the mental resources which are freed up by the cognitive offloading afforded by these digital devices,” Dr Chong says.

RELATED: The impact of technology on caregiving in Singapore

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.