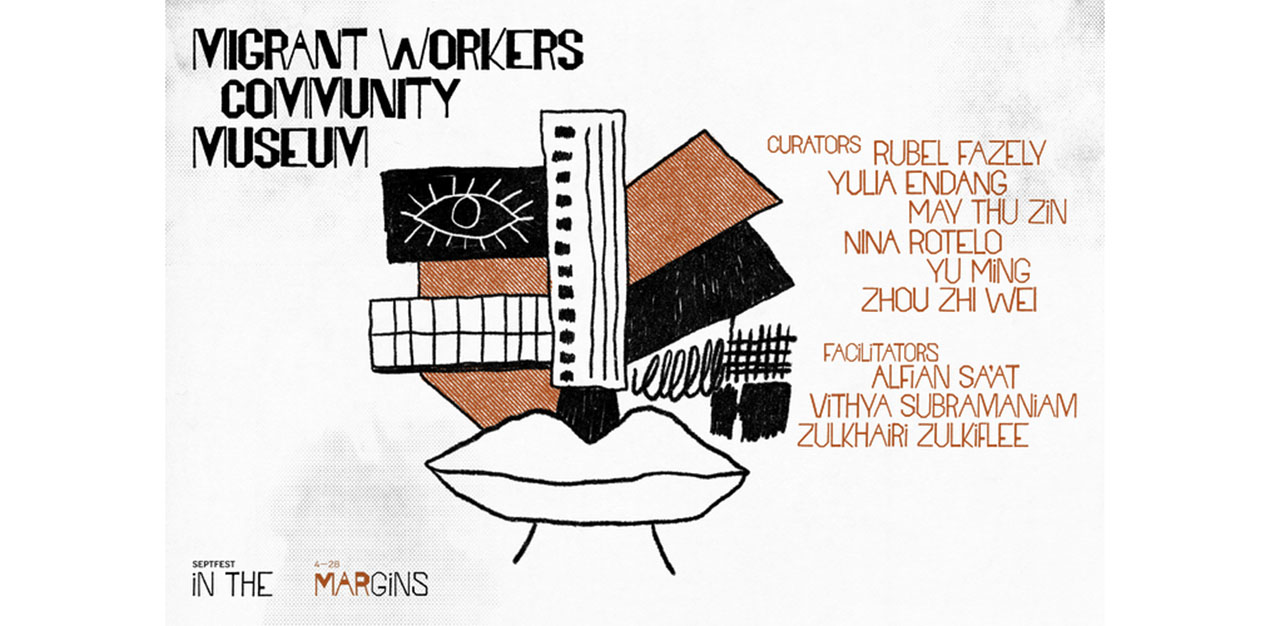

Frequently unseen and underappreciated, low-wage migrant workers are now being celebrated for their contribution to Singapore through the Migrant Workers Community Museum. Curated by six workers, the museum showcases aspects of their personal and professional lives using objects that relate to their arrival here, living conditions, jobs, beliefs and hopes, as well as what they do for leisure. As part of The Substation’s SeptFest 2021, the museum will run until 28 March.

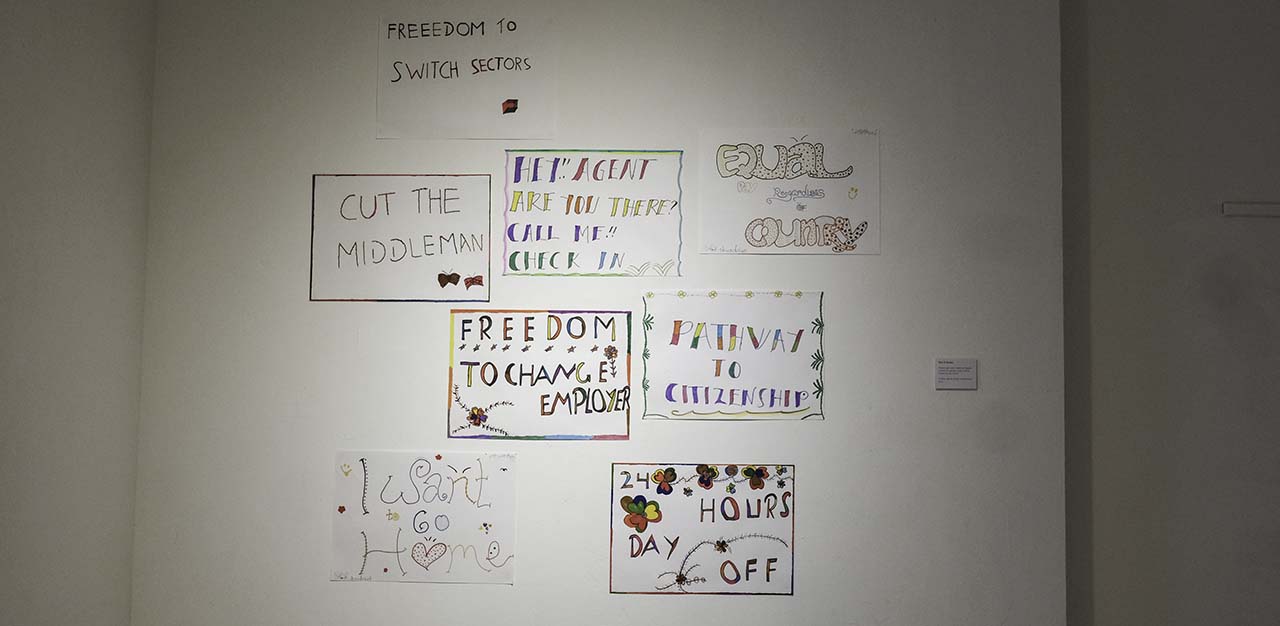

As you step into the Migrant Workers Community Museum at The Substation, a colourful chorus of slogans greets the visitor on the right. Phrases like ‘Cut the Middleman’, ‘I Want to Go Home’, ‘24 Hours Day Off’ and ‘Freedom to Change Employers’ occupy this stark wall, which the accompanying caption explains, “express some of their wishes [migrant workers’] for the future.”

The museum’s co-facilitator Alfian Sa’at, a renowned Singaporean writer, poet and playwright, thinks that while the display has been called the Wall of Wishes, he finds the term “anodyne”: “If I wanted to be more radical about it,” he says, “I think I would call them protest signs.”

One of the museum’s six migrant worker curators, Saturnina De los Santos Rotelo, points to the hope for a mandatory 24-hour day off for domestic workers, like herself, as holding the most meaning for her.

“The most important thing is the day off for me, because of all the hard work we do,” she says. “I don’t want to talk. I don’t want to do anything. Just sit down and relax my mind and my body. After that, I will call my family peacefully without someone listening to me.”

FIlipina Ms Rotelo, or ‘Cute’, as her friends affectionately call her, has worked in Singapore for 23 years. Being the oldest of eight children in her family, the former teacher took it upon herself to leave home at the age of 27, when her father fell ill, to work in Singapore so she could help pay for his medication and a mounting debt. Through this selfless act, she was able to support her family, paying for her siblings’ education and building a home for them.

I/On the margins

Some one million low-wage migrants from countries like Bangladesh, China, Indonesia, India, Myanmar and the Philippines work and live in this city state. They often find jobs in the construction, marine and service sectors, and also as domestic workers.

Many have been here for decades but this is the first time a museum dedicated to this often invisible, transient community has been created, albeit temporarily (until 28 March), as part of The Substation’s SeptFest 2021, celebrating art, culture and community.

Mr Alfian says that he was invited by The Substation’s Co-Artistic Director Raka Maitra to produce a piece of work for the festival, aligned with this year’s theme In the Margins.

“When I think of people who are marginal in Singapore, I usually think of people of minority status. So sexual minorities, ethnic minorities,” he explains. “It wasn’t until a little later that the figure of the migrant worker surfaced in my mind. To my shame, because they are so marginal they don’t even register immediately when I think of people who are in the margins.”

He wanted to do something out of his “comfort zone” and fell upon the idea of a community museum. Without any prior experience on how to mount an exhibition, he roped in co-facilitators Zul Zulkiflee, an artist-curator and author and anthropologist-in-training Vithya Subramaniam.

“The Substation is precisely the kind of place that allows you to try something out, that won’t ask you questions like, ‘Do you know what you’re doing?’,” he elaborates. “Because the ethos here is you learn from doing and sometimes you learn best by failing.”

Co-facilitator Ms Vithya explains that calling it a ‘museum’, rather than an ‘exhibit’, lends it legitimacy: “A museum is in a way an authorising voice. It gives some kind of permanence to the stories that are being told.”

She adds, “It’s also about not just showing the experience of migrant workers, but reflecting it back to them and [saying] ‘We hear your stories. And they are not just interesting for interesting’s sake. It’s important stories that your peers need to hear that we [Singaporeans] need to hear.’”

Creating place and meaning for communities in transit

Selecting and placing these personal and professional artefacts in a formalised setting serves to speak to the materiality, memories and histories of migrants, whose labour and bodies are often undervalued in Singapore.

“There’s something about putting all these objects that we take for granted within a museum setting, that gives them a certain value and aura and presence,” posits Mr Alfian. “If I put them on the street no one is going to look. But the minute you put it in a white cube context, shine a spotlight on it, put a caption beside it, then it’s something that you start paying attention to.”

Like the bright red words, DIRTY, DIFFICULT, DANGEROUS, that shout for attention along three consecutive pillars in The Substation Gallery. These refer to the types of jobs that migrant workers are typically employed to do that the local population find undesirable.

“We put it out there in very stark terms, the three Ds of migrant labour. Stuff that Singaporeans don’t want to do. And it’s weird, right? Because one should think that work that is difficult and dangerous should be highly paid. But it’s not. And that’s the unfortunate thing about it.”

Outraged by the injustice of “labour exploitation”, Mr Alfian wonders if the country is profiting off the labour of “indentured” workers”. He calls this inequitable system the “dark side of Singapore’s economic prosperity”.

“What is the barest minimum that you can get away with in terms of extracting labour, and yet not giving these people certain rights and welfare? I wish we examined that a little bit; how our very extreme pro-business inclinations have disenfranchised so many people.”

Migrant workers curating their own narratives

Centring the migrant worker experience – their voices and narratives, by inviting them onboard as curators, was essential to the process of designing the museum. It also addressed inherent power imbalances within society.

As a student of anthropology, Ms Vithya’s role was to consider which objects to include in the museum, while prioritising the stories of migrant curators. In making these decisions, she notes that they were conscious about not perpetuating existing biases and stereotypes about migrant workers.

“That was definitely critical, to not just reiterate what we think we know. Which is why you will see, besides more official-sounding [institutionalised] descriptions on what the object is, and where it’s from, quotes from the curators themselves, explaining their feelings about the objects or their feelings about the process that the object represents. That was really critical in centring the workers’ voice, the curators’ voice.”

For instance, alongside an assembly of tools used by migrant workers in their various jobs, sits a quote instead of a description. It reads, “We are domestic workers, but we can also be gardener, masseuse, teacher, electrician, nurse. Some people call us Jack of all trades, and master of none.”

Besides Ms Rotelo, Bangladesh national Rubel Fazely, Indonesian Yulia Endang, May Thu Zin from Myanmar and Yu Ming and Zhou Zhi Wei from China also agreed to participate. Discussions between the parties began in November last year, over four Sundays. These weekly workshops allowed for open and vibrant conversations between the facilitators and curators, who revealed their joys, victories, fears and hardships.

“I was quite surprised by how segregated they were. Someone like Rubel, for example, who works in construction, for the first seven years of his life in Singapore, he did not have a single Singaporean friend. So he only knew Singaporeans as his foreman and bosses,” shares Mr Alfian. “That for me was kind of mind-blowing. There’s really no attempt to integrate them into society.”

He cites another story from Rubel’s friend, who would never sit down on public transport: “When they first come to Singapore, they are warned, ‘Don’t make Singaporeans upset or angry. Always be aware of what you’re doing in public,’” he says incredulously. “So there’s a lot of self-effacing, body-disciplining that happens. And they only will feel free if there’s a certain enclave, like Little India or Lucky Plaza. Otherwise in public, there’s always a sense that ‘I must fold myself into something that is as unobtrusive as possible.’”

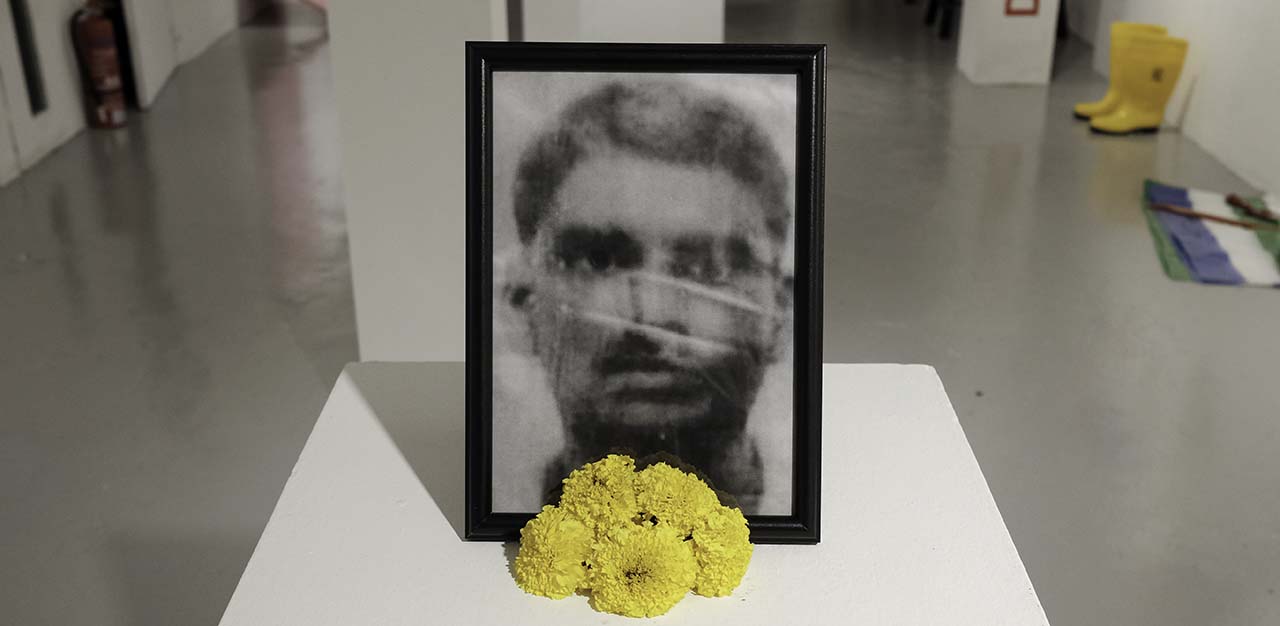

A concerted effort was also made to avoid existing and accepted narratives around controversial events involving migrant workers, like the 2013 ‘Little India Riot’ that played to the public’s negative perceptions.

“If the prevailing narrative about the Little India Riot is that alcohol caused it, and we know that’s not the case, we don’t want to perpetuate that stereotype,” explains Ms Vithya. “We tried to return it back to the original moment. What was crucial about that day is that someone died [Indian national Sakthivel Kumaravelu] and his friends got really upset… And so that’s the object [fact] we centre.”

Everyone has baggage

On another wall below the biographies of the six curators stands a line of backpacks and suitcases, in varying styles and sizes. These might have carried the worldly possessions of their owners when they arrived in Singapore for the first time. Ms Yulia’s black rucksack stands out for being the smallest. She had only packed the bare essentials for the move here, like t-shirts and shorts, toiletries and personal documents: “I was worried that I won’t be able to work here, as during my time the Singapore Government requires newcomers to pass the English test; only then we can apply for the Work Permit.”

Her English proficiency would prove not to be an obstacle. Since arriving nearly 15 years ago from a village in Ciamis in West Java, Indonesia, Ms Yulia has earned an English Literature degree from the Open University of Indonesia and won second prize in the Migrant Worker Poetry Competition, in 2019. She also runs a YouTube channel where she posts regular vlogs (video blog) in English and Bahasa.

She was excited but also nervous to be part of the Migrant Workers Community Museum, because the topic of migrant workers was “a sensitive issue”.

“I was a bit concerned whether I will be able to voice out our fellow migrant workers’ voices accurately.” But she had a good time: “We shared our experience working here, our culture and family and food. We also did some exercises conducted by facilitators. My best moment is when we laughed together.”

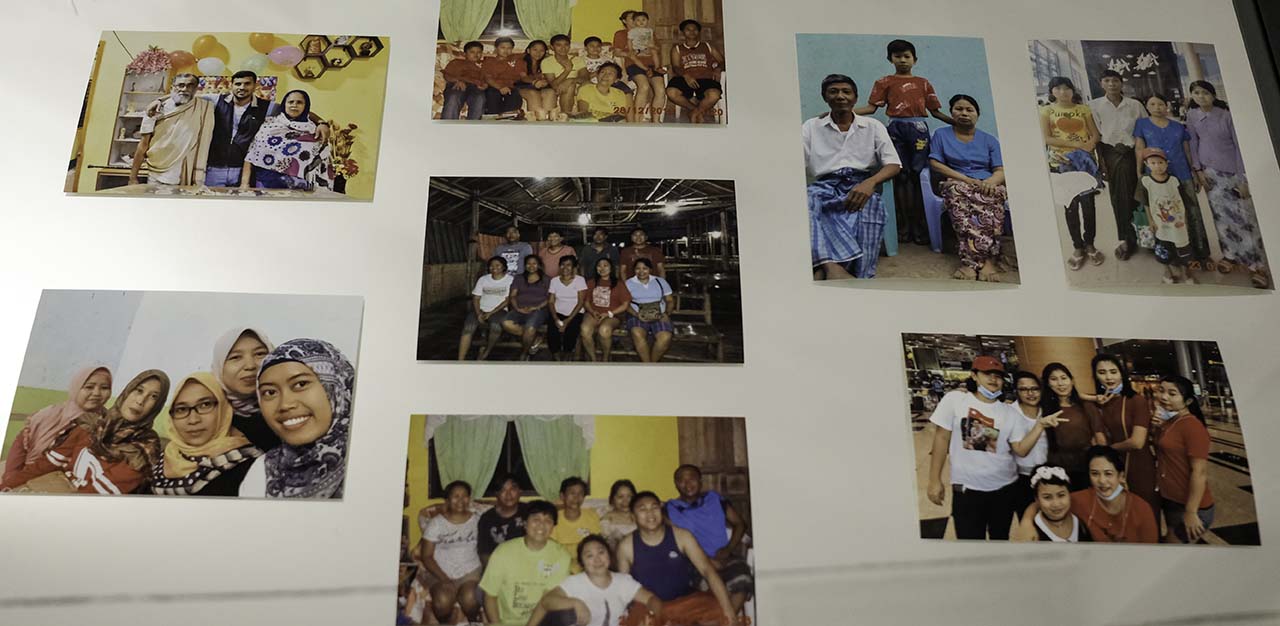

Among a spread of photographs on a table towards the back of the gallery, Ms Yulia’s radiant smile shines from a snapshot of her with friends. Their framed faces exude a palpable strength: “There have been ups and downs, but I learned a lot too,” she says. “I never imagined that life here would be that easy, as we have to adapt with the differences. But all hardships and struggles that I’ve been through have taught me valuable lessons.”

Civil rights activist Jolovan Wham, who has actively campaigned for the rights of Singapore’s migrant worker community for nearly 20 years, thinks the museum is a “good snapshot” of their lives, thoughts and struggles.

“I think the fundamental problem hasn’t changed, which is that they’re just not treated as people with equal rights,” he says. “We just use them when we need and throw them when we don’t. And the policy encourages this. It’s simply because they don’t have political power… Low-wage migrants everywhere around the world will face this kind of problem. It’s not a uniquely Singaporean problem… There’s definitely a lot of erasure [of migrant workers], which is why this is powerful.”

For Mr Wham, it is the replica of Mr Rubel’s dormitory bunk bed that strikes the strongest chord.

“You have so little space in the dorm, so everything that belongs to you in this world is contained in that bit of space. And for two people. That is quite stark for me even though I have seen these places,” he shares. “This is just a sanitised version, because you have an air-conditioned gallery, but it’s symbolic of the kind of spaces that they occupy in Singapore. You’re not given much space; physically, symbolically, politically, culturally, socially and mentally.”

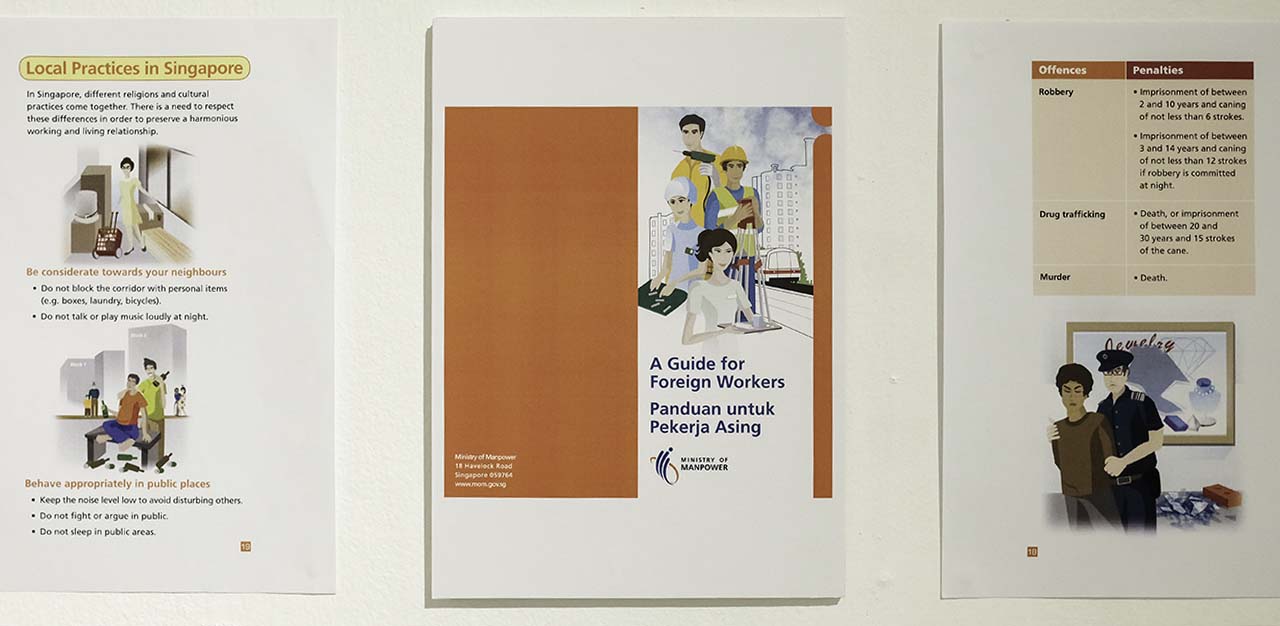

The Guide for Foreign Workers was another item that he found confronting. This booklet is given to all new arrivals to Singapore by the Ministry of Manpower. It was the first time Mr Wham had scrutinised its pages.

“I realised this is really classist shit. You never [give] someone with an employment pass or so-called higher-salaried migrants [a booklet] that says these are our laws, don’t break them. [It’s] very condescending,” he asserts.

Not robots but humans

‘Courage’, ‘determination’ and ‘resilience’, are words often used to describe migrant workers in the media. But at the Migrant Workers Community Museum, where an unfiltered lens presents a glimpse into their lives, these words fail to fully capture what low-waged migrants endure in order to improve the lives of loved ones.

Ms Yulia says that the museum is important to showcase the contribution of migrant workers to Singapore’s development: “I hope visitors will get to know more about us not just in terms of the sector we are working, but as humans who have the same hobbies and activities like everyone else.”

While Ms Rotelo wishes for visitors to the museum to realise that domestic workers are humans not robots: “I’m so proud that this museum was built, because I want to show people that migrants contribute to Singapore [with] our hard work…We are not just a stupid helper doing the housework, but we are extraordinary women who [can] do a lot of things…They [employers] should appreciate it”

She adds, “If you love your helper, they will love you more…You care for them, they will care more for you…take care of everything inside the house, your food, your children, the family, your household.”

As Ms Rotelo reflects on her life in Singapore, before she returns to the Philippines for good in July, she says her biggest regret is not being able to see her parents before they died. But despite her struggles, she believes that she has accomplished her dreams since the first time she arrived here with that suitcase [displayed in the museum].

“Even though I never get married…I’m happy that I give my siblings and my family a good life and I sacrifice myself for that,” she says.

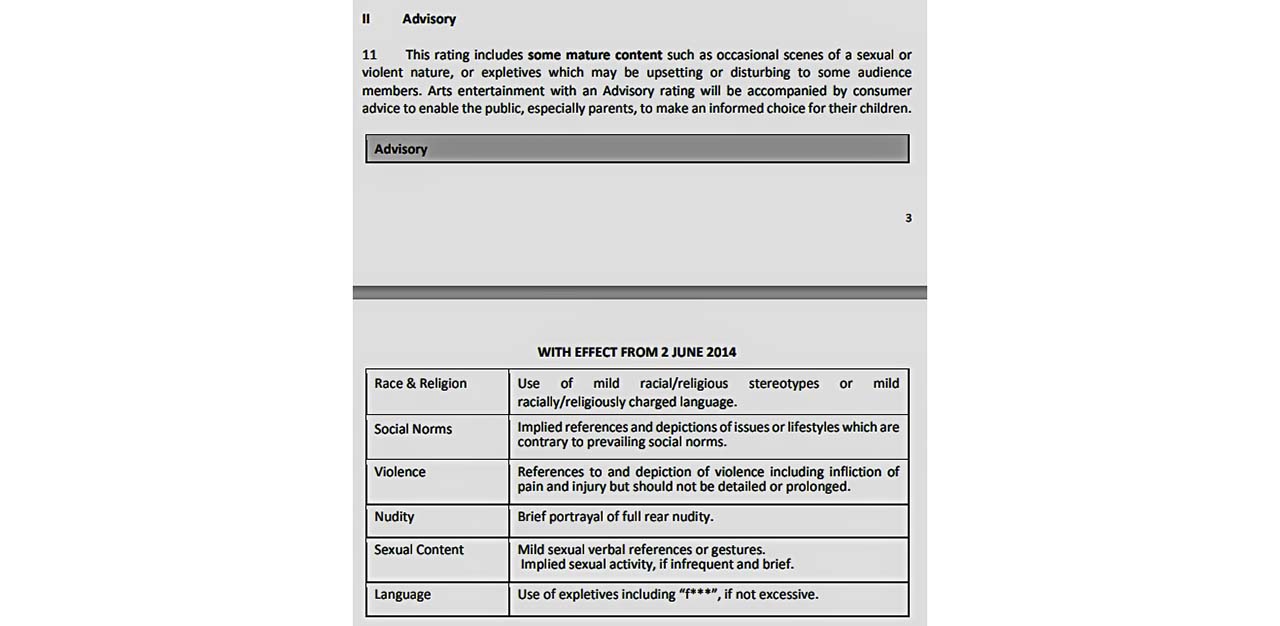

Note: The Infocomm Media Development Authority has rated the Migrant Workers Community Museum ‘Advisory’ with “the consumer advice ‘Some Mature Content’ as it contains socio-political references.” To which Mr Alfian responds, “I’m completely rolling my eyes, because obviously migrant labour issues are socio-political. Many art exhibitions are socio-political, the news is socio-political, but do you have a warning before it saying children please don’t watch news? I suspect this rating is slapped on [the museum], because it doesn’t parrot a lot of official narratives about migrant labour.”