When you think of taxidermy outside of the museum, perhaps the image that surfaces in your mind is that of a gruff-looking hunter in a bloodstained apron, standing next to hulking deer and bear heads mounted on an antique wall. Or you might picture a goth woman adorned with trinkets made from the bones of a small creature, who keeps animal foetuses suspended in jars of murky yellow liquid on her shelf.

It might also be easy to assume that someone who enjoys collecting or attending to animal cadavers for a living is a closet serial killer, fringe-dweller, or just morbid. However, these are merely narrow stereotypes that Malaysian taxidermist and artist Anna Razak has set out to change about her industry.

“Some people really think we practise voodoo or witchcraft,” Ms. Razak says. “All we’re doing is preserving and memorialising dead animals as an alternative to burying or cremating them.”

Taxidermy is the ancient art of preserving dead animals for the purpose of display or education, employing different techniques to reconstruct them in a three-dimensional, life-like state. The word taxidermy is derived from the Greek taxis, which means “arrangement”, and derma, “skin”. According to the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (National Museum of Natural History) in France, whether the true beginnings of taxidermy stemmed from ornamental or scientific reasons remains largely unknown. Despite its long history, taxidermy is becoming a dying art form, especially in Asia.

“Getting more people to learn about and appreciate taxidermy would be a dream come true,” says Ms. Razak, whose love for her work shines through. “I think it’s about time I bring it forward and share it with the rest of the world.”

TheHomeGround Asia sits down with Anna Razak to find out what it takes to become a successful taxidermist in Malaysia, the common misconceptions people have about the industry, and the challenges she faces in venturing off the beaten path.

TheHomeGround Asia (THG): Tell me about your taxidermy process.

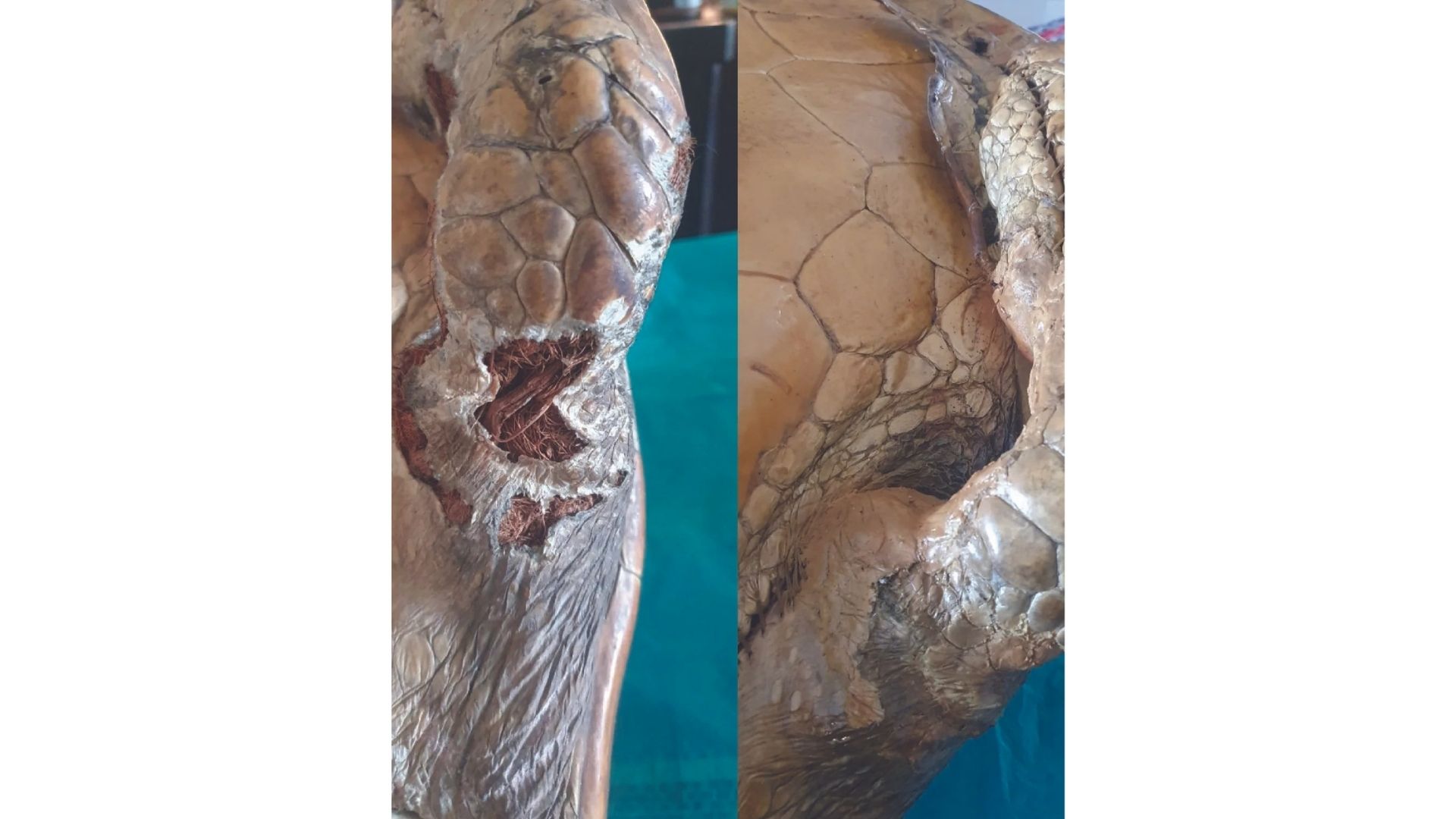

Anna Razak (AR): When taxidermists first receive a specimen, it is placed in the freezer immediately to prevent any decay from taking root, and kept there until we’re ready to work on it. When the time comes, we would have to thaw the body, which I do naturally by leaving it out for a few hours. Once it has thawed, we’ll carry out the first step: Skinning. At first, customers would always ask, “What about the internal organs and the bones?” All of the animal’s insides are removed. In taxidermy, we only preserve the animal’s skin. Some people get me to preserve their pet’s innards in a jar, while others prefer not to — in that case, I usually keep them for my own collection.

After the skinning is done, the leftover fat and meat tissue must be removed. This procedure is called fleshing. Then we rebuild the form of the animal. This is why the body — removed whole during the skinning process — is usually kept for reference. I use coconut husks, cotton, or anything that can be moulded into the right shape. The bones are replaced by wires, after which I’ll sew the whole thing back up. Lastly comes the mounting, where the finished taxidermy is fixed in its desired position. Drying takes up to two to three weeks depending on the size of the animal.

THG: How do you ensure the animal looks the same as it did while it was alive, and does not decompose after your work is done?

AR: I always tell my clients that I can’t produce a hundred percent accurate replica of their pets, because it is sadly quite an impossible challenge, especially after the finished taxidermy has dried and hardened. I’ve had pet owners ask if they can hold their taxidermied pets or cuddle them like stuffed animals, but the bacteria we carry as humans would infect and degrade the taxidermy over time if they were to do so.

If you carry out the basic processes correctly, the chances of decomposition are really zero to none. However, the humid weather in Malaysia provides the perfect breeding ground for dust mites and other pests. For this reason, we put most of our completed specimens in a glass display case. Many people assume that once the work is done, the taxidermy can just be left alone, but I always advise my clients to check for the possibility of pests. The sooner you realise there is a problem, the easier it would be to get rid of it.

THG: What would you say it takes for someone to be a taxidermist, seeing as you said the job isn’t for everyone?

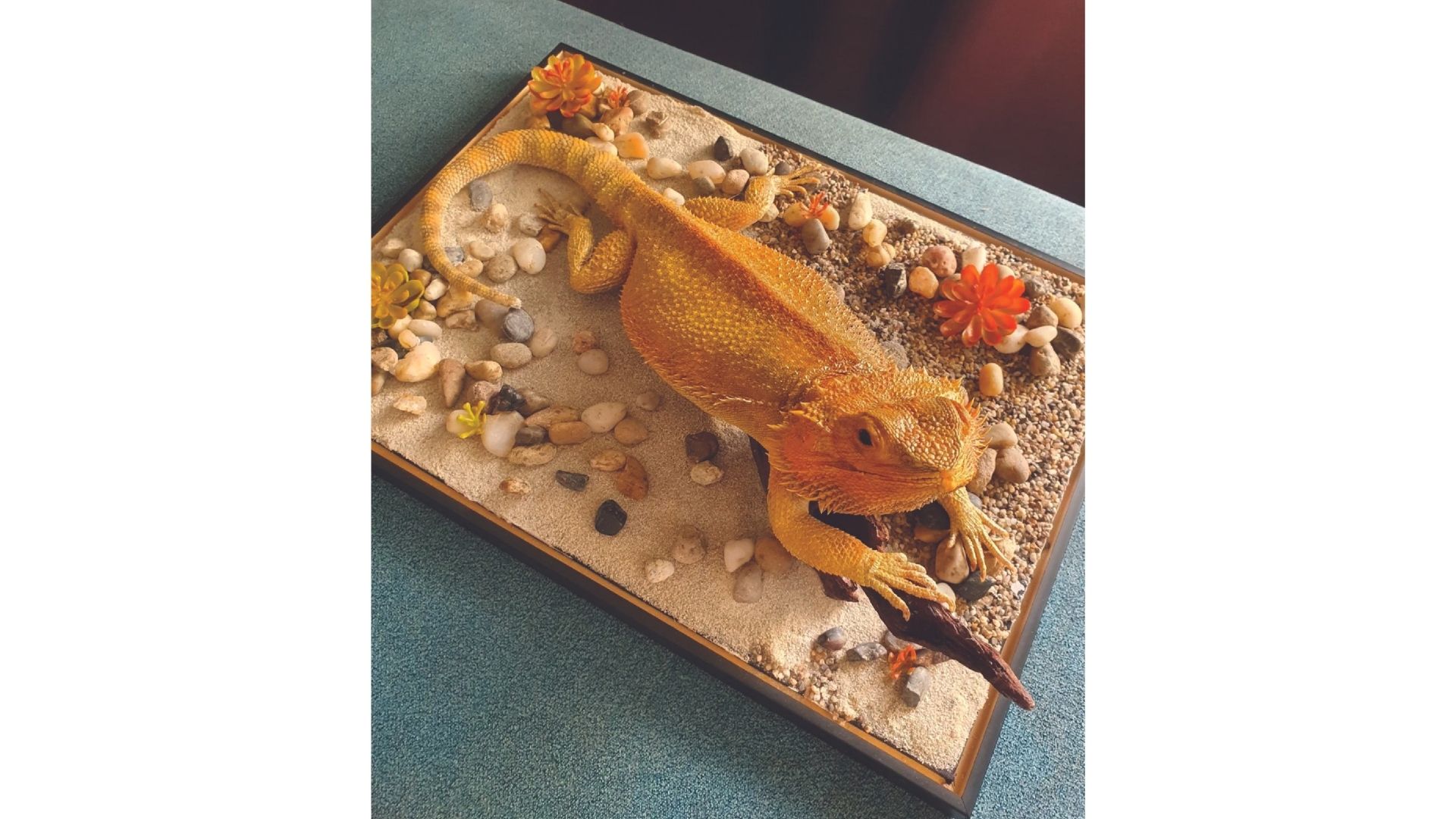

AR: Passion is key, no doubt. Without it, a lot of artists lose momentum and motivation to keep at it. A job dealing with animal bodies is also not for people who cannot stand the sight of blood and organs. Besides that, it takes a lot of discipline, patience, and perseverance to master the craft. There are additional skills you need, like an understanding of anatomy and certain artistic inclinations, such as painting and the ability to work with resin art to create fake eyeballs.

THG: How did you learn to do this professionally?

AR: I’ve been in the industry since 2017. In the absence of taxidermy schools in Malaysia when I first started, the Internet became my best friend — that’s where I picked up most of my skills and knowledge. But I was unsatisfied because I’m a hands-on learner and would prefer to have someone on hand to guide me and answer my questions.

As such, I got in touch with Dr Norman Affendi, a vet who was working on taxidermy for the museum, and he also happened to be looking for an apprentice. I started as a student, but we eventually developed a great relationship and have now established our own business together as partners. So, I was self-taught for the most part, until my partner took me under his wing. I started slow and practised on small rodents, lacking the confidence to work on clients’ pets or big specimens. With his support, I’ve grown and improved tremendously as a professional taxidermist.

THG: It seems like a difficult and emotional process to clean the insides of dead animals to many — especially a beloved pet. How do you cope with it?

AR: When done correctly, the taxidermy process doesn’t usually involve much blood. The procedure is akin to taking off your sock. With that said, I do have a strong tolerance for gore, and I understand that this isn’t a job for everyone. And I don’t view taxidermy as an emotional or sad process. I feel a sense of responsibility for being entrusted with the task of honouring my clients’ furry family members, and I take a lot of pride in my work.

THG: What are some of the challenges you’ve faced in becoming a taxidermist?

AR: Being a taxidermist in Asia definitely isn’t easy. For example, I don’t receive a lot of support because there are so few of us. We don’t have a community where we can discuss, share ideas, and work together. On top of that, many of the tools and materials we need aren’t available here. In the US, they sell ready-made animal forms, but we have to resort to making our own. If I had the luxury of buying pre-made bodies, a lot of time would be saved on the reconstructing and stuffing process. Other tools, like the specific knife we use for fleshing, also cannot be found in Asia, and online shipping is too expensive. So, my partner and I have no choice but to custom-make our own tools.

Apart from that, it is also a challenge to gain acceptance from the general public. Taxidermy is still considered taboo in Asia, as most people believe that animals should be buried or cremated. The idea of preserving your pet is seen as crazy, for lack of a better word. People always tell me, “Oh, you have a lot of dead animals in your house? You must be crazy.” But I’m trying to change that perception by exposing more people to taxidermy and sharing about my work.

THG: What do your loved ones think of your current profession?

AR: My amazing husband is one of the biggest reasons I’m a taxidermist today. He was hugely supportive when I first expressed my budding interest in pursuing this as a career, and continued pushing me to chase that passion. Even now, he remains very enthusiastic about what I do, and gets incredibly excited about my new specimens. He also buys me cool tools to help me improve my craft. For example, he recently bought me an airbrush machine, which is very helpful for working on reptiles and fish.

My parents were, at first, vehemently against the idea, but they eventually grew to support my ambitions. My mom gets excited now, and she is always asking what I’m working on next and prodding me to send her photos. My dad, too, has begun to see the beauty behind taxidermy the way I do. My friends are wonderful and very supportive — they love my work and even enjoy bragging about me, which makes me very happy. Overall, I’m fortunate enough to say that I have a great support system.

THG: What are some misconceptions people have about taxidermists and the industry?

AR: The worst thing is that some people assume we’re murderers, that we kill these animals for the purpose of preserving them. This cannot be farther from the truth: We love animals, dead or alive, and the idea of killing one is absolutely unthinkable to me. I know some villagers living near the jungle who would hunt animals to feed their families, which I believe is their prerogative. However, we are devoutly against murdering for sport. We have declined to work with hunters who kill animals to collect trophies as well as people who hunt down endangered species, and we report these cases to the wildlife department immediately. As much as we love our art, we are also about conservation and loving animals.

Other than people who associate taxidermy with witchcraft and black magic, there are also those who view it as disrespectful to the dead. I personally believe it is the highest form of respect you can pay to an animal that has passed — giving it new life by preserving it to keep with you forever.

THG: What drives your love for this rare and under-appreciated art form?

AR: That’s exactly it — what drives me is the fact that it is rare and under-appreciated! It’s really dying out in Asia. Even if you do encounter a practitioner, chances are they’re doing it for a museum and aren’t driven by the passion or appreciation for it as an art form. Starting from next month, I’m conducting regular public workshops on taxidermy, which is a big step forward. Previously, we’ve only taught at the museum, which is limited to employees. My goal is to get rid of the stigma attached to taxidermy and help the community grow in Malaysia.

Besides that, my 15-year-old cat also inspired me to pick up taxidermy — she is my best friend and I love her so much. The idea of burying or cremating her is unfathomable to both my husband and me, and we’ve always known we would want to have her preserved after she is gone.

THG: What would you like people to understand about taxidermy?

AR: Customers usually expect that they can pick up their finished taxidermy within a week, but this is a long and tedious procedure. I typically take up to three to four months to finish preserving a dog. High quality taxidermy demands great attention to detail, so I spend a lot of time perfecting every step of the process.

With death being a taboo subject in Asia, I’d also like to dispel the idea that taxidermy is gross, dark, or weird. If you have any questions or doubts about taxidermy, just reach out to a taxidermist, and we’re always happy to share our knowledge. I love this job and I’m proud of my work — I always do my best for my clients, who trust me with the task of paying homage to the animal friend they have loved for so many years.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.