In November last year, End FGC Singapore launched Singapore’s first pilot study on the issue of female genital cutting within the Muslim community. Of the 364 Muslim women surveyed, 76.4 per cent had undergone the procedure. As End FGC Singapore continues to unpack the results of their survey, TheHomeGround Asia delves deeper into the issue of female genital cutting to understand what it is, why it is practised, and why it is problematic.

Diana Rahim, editor of social activism platform Beyond the Hijab, had always thought that undergoing sunat perempuan, otherwise known as female genital cutting (FGC), was a normal affair. She had been cut as a child, so were her siblings. It was only when she was in university that she first learnt what had been done to her was “not actually normal for a lot of other people.”

She says: “I felt such a disconnect because I have been cut, but for myself and a lot of Muslim girls who have been cut, it has been so normalised in our reality. It takes time for us to register that it’s actually not necessary.”

On the other side of the world in the United States, Mariya Taher shares a similar experience: “[Female genital cutting] was something all women underwent in the Dawoodi Bohra community [a subject of Shia Islam, which Ms Taher is a part of], it wasn’t something that was questioned.”

In fact, it was celebrated: “After I had it done, and after my sister had it done we had small parties to celebrate with other girls our age.”

Like Ms Diana, Ms Taher only started questioning the practice of FGC when she entered high school, and a friend of hers expressed her displeasure about FGC. This prompted her to further her research, and eventually led to her uniting with a group of four other women to establish Sahiyo, an organisation dedicated to the abolishment of FGC in Asian communities.

But what led these women to speak out and take action against FGC? And if the practice is condemned by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a “violation of the human rights of girls and women”, why does it continue to happen?

To understand that, it is first paramount to grasp exactly what FGC constitutes, and the complex social, cultural, and religious reasons that continue to perpetuate this practice.

The complexities behind female genital cutting

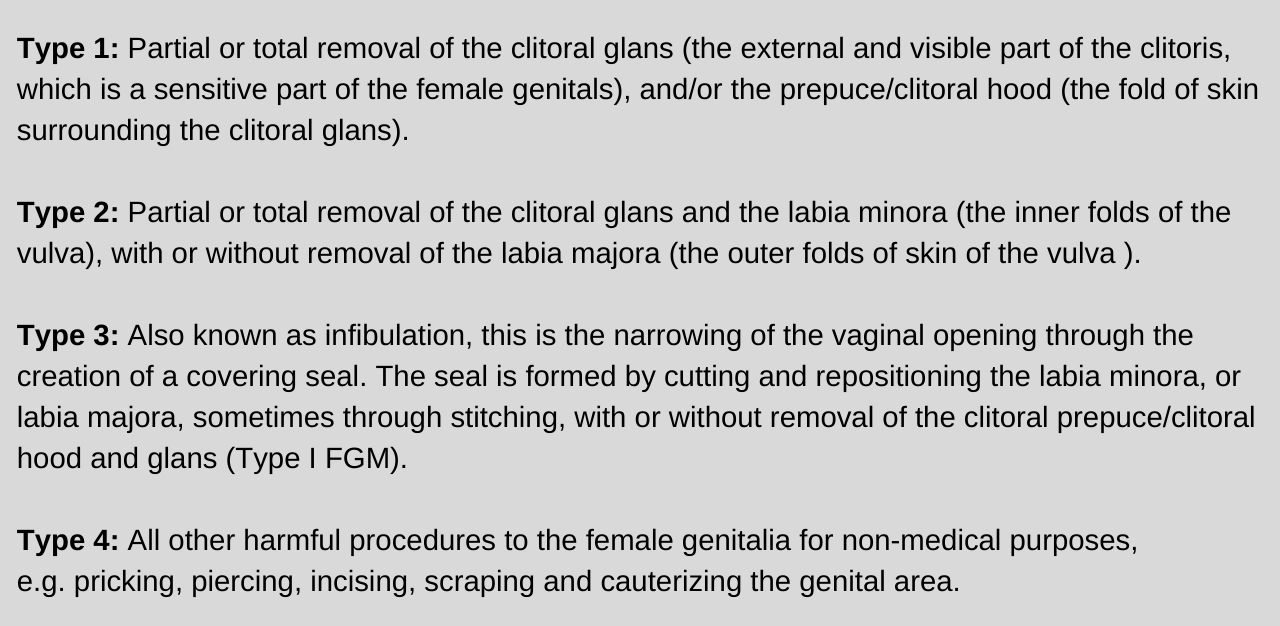

According to WHO, FGC (sometimes known as female genital mutilation) comprises “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons”. The practice of FGC has been classified into four different types based on its physical severity.

Orchid Project, a UK-based NGO that aims to end FGC, estimates that FGC affects over 200 million women and girls worldwide across 96 countries, although only 30 countries report national data on affected populations. In Singapore alone, community-led movement End FGC Singapore estimates that of the 364 women surveyed, 76.4 per cent had undergone FGC Types 1, 2, and 4, or an estimated 173,000 women and girls if extrapolated nationwide.

Reasons vary as to why this procedure is performed. Ms Taher explains: “There have been reasons for health and hygiene… aesthetics, cleanliness, the idea that it looks cleaner, or cleanliness in the idea of religious purity, that it will help clarify the spirit.”

She adds: “Sometimes, I will hear reasonings that women are not supposed to be sexual in Islam, so that’s why it’s done… But overall, it’s a social norm. It’s been justified in all these ways, so it continues generation after generation.”

Lo Riches, a policy and advocacy officer at Orchid Project, also highlights that oftentimes, FGC acts as an identity marker: “Noncompliance with the norm may bring sanctions, such as ostracisation from the community.”

Ms Taher provides the example of the Dawoodi Bohra community in the US: “Being part of the community allows you access to specific burial grounds and the ability to get marriage licenses, so if you’re socially sanctioned against, you might not have access to those.”

In other communities, FGC is believed to be a necessary rite of passage that ushers in adulthood. An anthropologist speaking to The Atlantic relates the tale of the Rendille people in northern Kenya, Africa, where FGC is not just a norm but a cause for celebration, and a precursor to womanhood.

Beyond health, hygiene, or cultural factors, religious obligation is also a plausible reason, according to WHO.

But, Ms Diana clarifies that FGC is not universally practised across religious communities commonly associated with the practice, such as Muslims, who number some 1.8 billion worldwide. Instead, it is dependent on the school of thought that the communities follow.

“[FGC] is not an Islamic imperative, is not mentioned in the Qur’an, and is not practised by the majority of Muslims worldwide,” highlights Ms Riches.

In response to queries from The HomeGround Asia, the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore maintains that “any form of procedure which has been medically proven to bring harm, including female genital mutilation, or FGM, should be avoided”, referencing the Islamic legal maxim of “All forms of harm must be removed” and “Do not inflict injury nor requite one injury with another.”

In fact, it is widely acknowledged, including in this paper by human rights NGO Amnesty International, that the practice of FGC predates Islam.

This amalgamation of factors has resulted in the persistent practice of FGC around the world, even in the presence of research citing negative health consequences. Various religious leaders have also offered a contrarian view of this practice, such as the former Grand Mufti of Egypt Ali Gomaa and Iraq’s Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Husayni al-Sistani.

Why is female genital cutting a concern?

Ms Diana insists that the main issue is how FGC is an act of controlling the female body or female desire.

“It is an act that is ideologically motivated, it’s so deterministic,” she says. “Is there no other way that we can talk to girls about questions of sexuality? Is there no other way that we can deal with our own anxieties over the sexuality of young girls?”

She adds: “It’s also an issue of body autonomy. If a person wants to go through this procedure, they have every right to when they are autonomous beings, when they are adults, but a baby is not given that choice.”

And a vast majority of girls are cut while they are young, with WHO estimating that most procedures occur before the age of 15. In Singapore, End FGC Singapore’s pilot study reveals that 75 per cent of girls are cut before their first birthday.

Ms Riches emphasises: “All forms of FGC violate the rights of women and girls and the practice is a form of gender-based violence.”

In some places, FGC has also become a medicalised practice, carried out by healthcare professionals. According to End FGC Singapore’s study, over 45 per cent of women who have been cut, were cut by a doctor.

Ms Taher explains that the medicalisation of FGC can further perpetuate the practice of FGC: “When it’s medicalised, there’s almost this idea that it is safer, because healthcare providers are doing it.”

FGC can also be potentially damaging to girls and women, physically and psychologically. According to WHO, FGC has “no medical justification nor health benefits”. On the contrary, it notes that FGC can result in an increased risk of physical, mental, and sexual health complications from childhood to later in life.

Female rights’ movement Equality Now has compiled stories from survivors of FGC, where they share their experiences and trauma, both physical and mental, after undergoing the procedure. One woman reported that her “sexual desire plummeted” and that she felt a “stinging burning sensation on [her] clitoris region” after giving birth to her child; while another reported painful periods and sexual experiences, and frequent urinary tract infections.

The lack of conversation surrounding female genital cutting

Perceived as a socially accepted norm amongst the communities who practise it, FGC often goes unquestioned. Ms Riches also suggests that the topic is often taboo and not discussed, since it involves a woman’s genitalia and her “modesty, purity, or control over their sexuality”.

What this means is that it usually remains a “woman’s issue”, says Ms Taher: “It’s quite common to hear that men weren’t aware of this… It’s also something that you were taught to be silent on, and those are dynamics that help with this continuing generation after generation.”

A culture of silence prevails, she says, and those who broach the topic “might be admonished” by elders and other women “enforcing this rule”. She adds that there can be “backlash and negative repercussions.”

There is also the shame often felt by those who have been cut.

“This is true for anybody who has undergone gender-based violence,” Ms Taher remarks. “Sometimes, there’s a lot of shame, even though it’s not your fault, and it’s just hard to talk about this happening to you.”

Some people might also prefer not to deal with the “emotional journey”, says Ms Diana: “You have to accept that to have been cut was not a good thing, that something has been done to your body.”

“There’s also this fear that it might play into the stereotype of a backward, savage Muslim who’s not keeping up with modern science,” she adds. “Sometimes, when people bring it up, it’s done by Islamophobes to say that the religion is backward, that they are not keeping up with the times, and that they do not treat women right.”

To this, Ms Diana urges the community at large to help where they can: “Push out the Islamophobes who jump on this issue for their own agendas… Support the people who are trying to address this issue, understand the anxieties and concerns, and support their voices. Try not to dominate a conversation and try to understand that it’s not just an issue about a cut, but it’s usually quite an emotional process for those who have been cut.”

Towards abolishing female genital cutting

Looking forward, Ms Taher is hopeful for the future: “We’re seeing more people coming out to speak about this. That fear [of speaking about it] is abating.”

And Ms Diana hopes that the conversations will continue, even if they are difficult to have: “[FGC] affects the bodies of all Muslims who have a vagina. If your body and life is going to be impacted, then of course, I would think you do have a right to have an opinion on this. If your body, your child’s body is going to be affected, you get to have a right in having this conversation, because it has a direct impact on you.”

Beyond conversations, Ms Taher points towards a holistic approach to address the issue, involving sectors such as education, outreach, law, and policy.

In the same vein, Ms Riches believes that more research needs to be done on these practices in countries where the phenomenon is more opaque. She also calls for “greater resourcing and investment” to support organisations and activists who are working to end FGC at national and community levels.

But, she emphasises that even though the wish is for this practice to end, it is still important to maintain support for survivors.

“We need to figure out how to provide care and support for all the women who have been impacted by this,” she says. “Thinking about how we work with healthcare providers, mental health therapists, and others who survivors might need to seek out.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.