The body positivity and neutrality movements have become increasingly popular in recent years, with more individuals advocating for greater self-acceptance of one’s shape and size, and challenging societal norms of what beauty looks like. TheHomeGround Asia speaks to three activists in the local body positivity space to find out how this movement has evolved in Singapore.

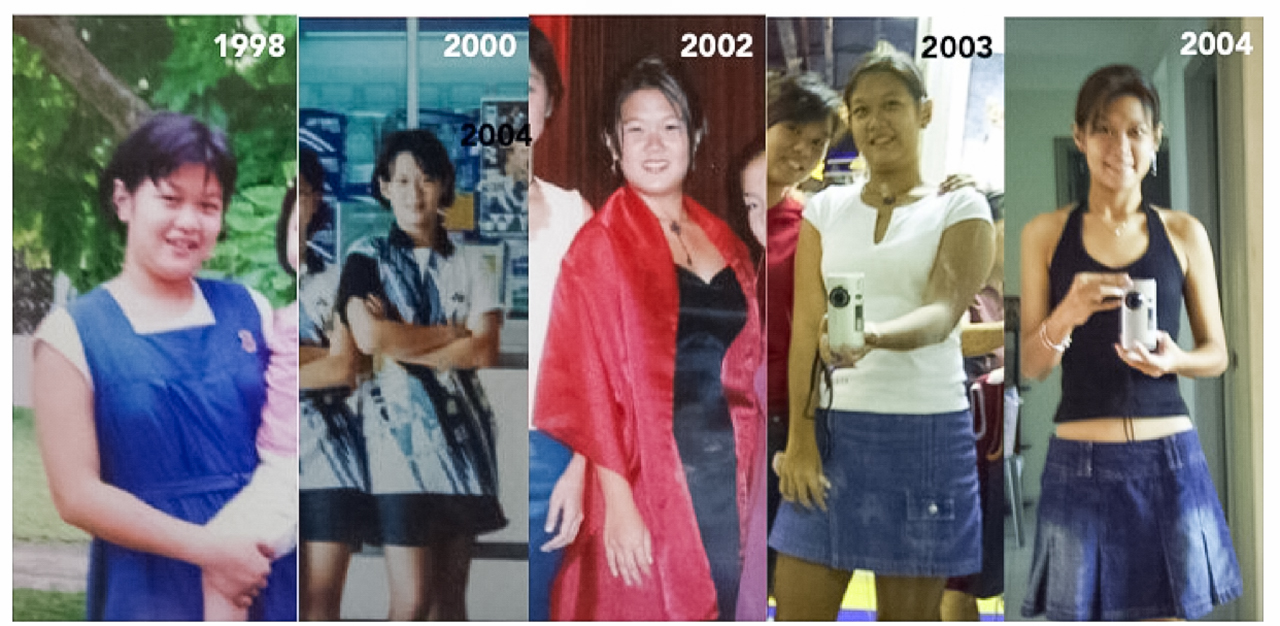

Cheryl Tay’s relationship with food had always been tricky. But the height of her struggles with body image issues happened at 18, two months prior to her A’ Level exams in 2004, when she decided to lose weight. As an athlete with the cross-country team at school, her obsession with exercising started with running.

“I would run 20km every day, 6km in the evening, and two to three hours of boxing – I’d play these DVDs, VCDs. I would do this every single day for two months, and I starved myself,” she says. “I will even wear my PE attire and put [on] an extra jacket and track pants, just so I could sweat more. I refused to eat. And I would try to run at the hottest time of the day.”

Ms Tay’s unforgiving lifestyle culminated in her losing over 20kg. She reveals that it was the darkest period of her life, during which she had resorted to self-harming as a coping mechanism.

“I became very skinny. I lost my personality,” she recalls. “I was self-harming or scratching myself, banging my head against the wall, punishing myself for eating because I would starve… I was weighing myself every hour, every half hour, counting calories. I didn’t want to drink water. It was ridiculous.”

She recounts an incident with her sister, who walked in on her banging her head against the wall: “She was crying and she was like, ‘why are you doing this to yourself, Jie? Why are you hurting yourself?’ She didn’t understand.”

Her parents tried to step in, suggesting that she see a doctor, but “made things worse” by calling her a “scarecrow” and “sick in the mind”. She attributes the language they used to a lack of awareness and education about eating disorders at that time.

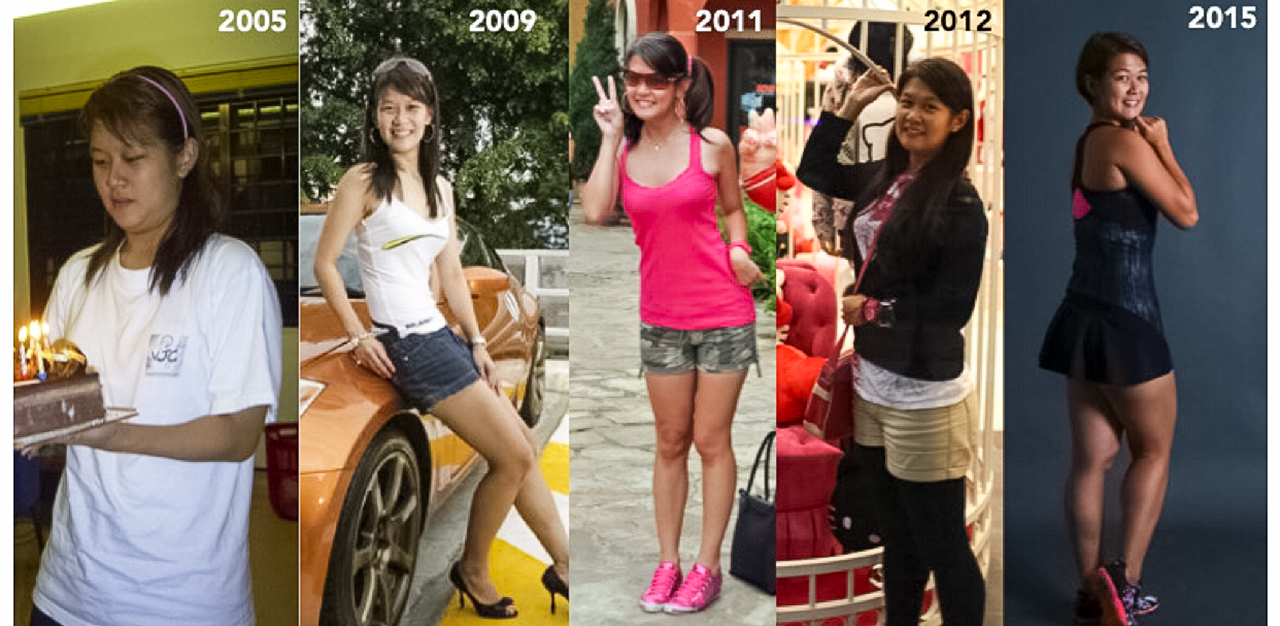

After struggling with her self-image for nearly a decade, she eventually gave up exercising in 2013.

“For a long time, fitness became a chore for me because I needed it to keep my body weight in check,” she explains. But when the passion for staying fit was reignited in 2015, her relationship with exercise improved and she started to experiment with crossfit and weightlifting. That was also the year that she ran her first half marathon.

Hoping to help others learn from her experience, Ms Tay decided to share her story. But instead, people started asking her for ways to lose weight, a response that convinced her something had to change.

It planted the seeds for body positivity movement Rock The Naked Truth, which she founded in 2016. The initiative aims to provide an accessible space for people to overcome their insecurities and build self-confidence. It also holds workshops and talks to raise awareness about body positivity.

Similarly, Mary Victor’s experiences with self-image came from a painful place: “I hated myself so much,” she says.

Having been bullied as a child, Ms Victor harboured a lot of resentment towards herself, which led to unhealthy coping mechanisms.

“It led to a lot of heavy things. Hurting myself and self-harming was something that came very naturally from that self-hate,” she shares. “I over-exercised and under-ate, and tried to puke out my food. All these negative feelings grew into a bigger form of self-hatred.”

The discovery of makeup helped her to gain more self-confidence, and set her on the path to healing and finally, feeling good about her body. “I felt a little bit more positive towards the way I looked at myself… I started focusing a lot on healing. I meditated a lot,” she says, adding that she read extensively to find out how to step out of the negativity.

Aarti Olivia Dubey’s road to activism began with her decision to venture into plus-size fashion, after she quit her job as a mental health therapist, in 2010. This stemmed from the desire to view herself and her body from a more positive perspective, and came alongside the start of her healing process from eating disorders, which she had struggled with for 20 years.

Ms Dubey launched her blog, Curves Become Her, in 2011, which explores the topic of plus-size fashion. “I saw all these amazing people on Instagram, and I thought plus-size fashion was really exciting. And it was nothing like I had ever done,” she says.

In 2018, she transitioned to body positivity advocacy, and is today a full-time activist, who addresses fat acceptance and body positivity, as well as other issues, such as mental health, racism and queer visibility.

“It is an interesting space to be in locally, because you’d be hard-pressed to find maybe three or four people like me, who go beyond body positivity,” she adds.

Her work with Curves Become Her has also furthered her personal journey with healing and self-acceptance. She recalls a body positivity workshop she participated in with other bloggers in 2013, which proved to be a life-changing experience.

“We basically reassessed different parts of our body. And we changed the narrative on how we look at our body, beyond what we see in the mirror,” she shares. “That was very powerful for me.

“We all have hang-ups about different parts of ourselves… Getting to the root of that, asking yourself ‘why?’, then taking a look into your school days, conversations you’ve had with your parents, and uncovering that, has really made a difference,” she elaborates.

Activists like Ms Dubey are part of the increasingly vocal body positivity movement, which promotes the acceptance of all shapes and sizes, and having a positive body image.

The evolution of the body positivity movement

While Ms Dubey acknowledges that the social climate towards body positivity has made great leaps over the past 10 years, a “far cry” from when she first started her journey, she describes the growth of Singapore’s body positivity movement as “five moves forward, two moves backwards.”

Fat shaming, though, continues to thrive, and is especially toxic on social media platform TikTok, she notes.

“Unfortunately, the fat community once again has been left behind. And they continue to struggle with daily experiences that they have. I constantly get trolled about my size,” she shares. “There’s still a long way to go.”

So while the necessity of talking about body positivity is being recognised, she thinks that such conversations tend to be relatively superficial.

“When it comes to the more nitty-gritty part of things, people still have difficulty, or they’re not really that interested,” she asserts.

Ms Victor thinks that the reception towards discussing topics like fat shaming and body positivity has grown warmer among younger generations, though such conversations tend to occur on a more personal level.

“They’re okay to talk about it to one or two persons they’re close to. There’s still some sort of improvement,” she says. “I feel like the one thing that’s changed is the younger generations’ perspective of how bodies [look] now.

“If I were to speak to somebody from Gen Z now, their perspective of seeing somebody of a bigger size or a different colour is very normal.”

She has also noticed that there is greater awareness and initiative to take part in such conversations. Based on her interactions with students, some have created their own movements for body neutrality and body positivity.

Ms Tay agrees, adding that she has noticed more discussions online that engage with body image.

“We have gotten better. I see a lot more people stepping out, taking their photos of [themselves] like, ‘This is what you see, but this is actually reality’,” she says.

She points out that there has been more corporate and individual interest in body positivity. The rise in popularity of body positivity, though, has led to more brands leveraging on the movement for commercial gain, as opposed to genuinely championing self-acceptance.

The rise of the body neutrality movement

Ms Victor’s foray into the body positivity movement started with a desire to make meaning of her self-hatred and negativity. Discovering makeup helped her to gain self-confidence. But she soon found herself looking for an avenue to transform her hatred into positivity, and to enable others to feel good about themselves.

This compelled her to launch The Body Within in September 2019. While it initially began as a body positive initiative, Ms Victor ended up falling into toxic body positivity instead, forcing herself to feel good about her body, even on days when she was not at her best.

“I managed to warp those negative feelings into toxic positivity, where I just push myself and say… ‘you’re going to get through this’, not really understanding or reflecting on the negativity of that feeling I had,” she explains.

Realising that such a mindset could be affecting many women and their relationships with their bodies, she changed the focus of The Body Within to ‘body neutrality’, which promotes self-acceptance and encourages people to adopt a neutral attitude towards their body.

“The whole point is to see yourself in a different light that’s more realistic,” says Ms Victor. “It can be negative or positive feelings; it’s realising those feelings.”

The Body Within has given her the opportunity to work on campaigns like #youbeyou, a collaboration with sustainable swimwear label UBU that promotes body acceptance, diversity and inclusion. Ms Victor shares that this was her biggest project to date. She relished the chance to challenge the convention of a ‘beach body’, which refers to a body that is deemed attractive enough to be seen in swimwear.

“Everyone’s still afraid of going out in a bikini because of the beach body perspective,” she says. “The beach body is the body that you have right now.”

How culture influences the body positivity movement

A culture of not being vocal about one’s feelings and fears is part of the reason why the body positivity movement has not grown as quickly, Ms Victor says.

“Nobody wants to talk about it, they’re scared to be vulnerable. They’re scared to talk about something that is sensitive,” she asserts. “It’s time we just start talking about it because if we don’t, it’s not gonna go anywhere.”

Ms Tay concurs: “I do have people coming up to me, sharing their stories with me privately. They’re like ‘but I don’t want to talk about it can?’ Then I’m like okay, but there’s no shame. They’re like ‘don’t want, later my boss see, or people judge me.’

“Why would people judge you for struggling with your body or your weight?”

Ms Dubey agrees, saying that people in Singapore are still “bashful” about sharing their opinions, and that there is a fear of being vocal about topics like body positivity. Instead, she receives private messages on social media that say, ‘I really appreciate your work’ and ‘It’s so brave that you do this, I don’t know if I could.’

Besides, she notes, even when people do talk about these topics, they skim the surface: “I have to explain very basic things, and [have] people fighting on semantics and linguistics, in the name of what people say, what society thinks,” she says. She contrasts this to an experience she had on invite-only chat app Clubhouse with a panel of other bloggers, where she found a greater level of understanding of such issues.

The future of body positivity in Singapore

Ms Tay believes that Singapore’s society is still largely conservative, which means that the public can be harsh and judgemental about the way people are supposed to look. She cites the reaction to plus-sized, body positivity influencers who post images online of themselves wearing lingerie.

“There will be a certain percentage [of viewers] that will be like ‘Oh wow, good for her’, but I think the larger part of the population will [say] ‘ee, so fat still wear this kind of thing’… We are still not very accepting as a society,” she opines.

Discussions are imperative for creating a community and helping those who are struggling with body image issues to feel seen, asserts Ms Victor. “It’s to make them feel like what [they are] going through is very normal,” she explains. “I think that if we speak up about issues like this, we’ll have a more representative society. People will feel more seen, more heard.”

While encouraging advocacy, she also advises would-be activists to be mindful of their influence, and insists that they educate themselves before guiding others, to avoid spreading misinformation.

And even with more brands catering to plus-size women, and fat acceptance movements starting to influence mainstream culture, Ms Dubey warns body-positive advocates against becoming the “token fat” representative in a “diversity campaign”.

Ultimately, Ms Dubey wants change to go beyond the individual and marketplace.

“Beyond the discussions that we are having right now, beyond the self-growth moments that people are having, I want to see this addressed on a systemic level,” she argues. “We as a society have a responsibility to tackle this… Helping people come to a place of more self-acceptance, so that there will be less animosity.

“It is a very high hope. But it’s a hope,” she says.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.

Where to find help:

Samaritans of Singapore: 1800 221-4444 (24 hours)

Institute of Mental Health: 6389-2222 (24 hours)

Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800 283-7019 (Mon to Fri, 9am to 6pm)

TOUCHline: 1800 377-2252 (Mon to Fri, 9am to 6pm)