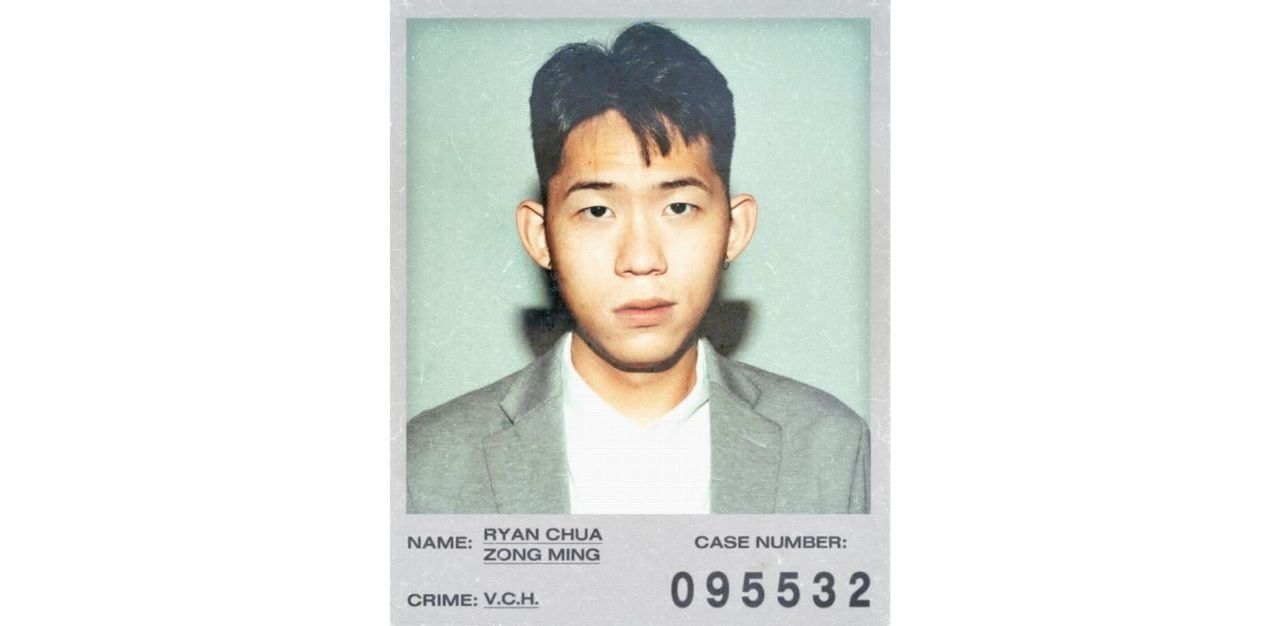

Through our weekly series In Conversation With, TheHomeGround Asia amplifies and celebrates the ideas, achievements and experiences of extraordinary individuals who are creating ripples in unique ways. As we approach the end of Pride Month, TheHomeGround Asia speaks with Singaporean multi-hyphenate, queer artist Isaac Chan.

Actor, budding musician, filmmaker, and gay – the latter, a part of Isaac Chan’s identity that he frequently alludes to during the interview. It is also how he describes his music.

“It’s just gay,” he states. “I like drama in my music.”

His debut single Hold It is an ode to an ex-boyfriend in the face of a long-distance relationship. It is a song perfect for the night, he says: “When you’re depressed, but other than that, when you’re in a cab home at 2am after a night out with your friends. I want it to be the kind of music you listen to in that state.”

The song was first penned in a moment of overwhelming emotion, when Mr Chan found himself home alone after sending his then-boyfriend off at the airport. With equal measures of helplessness, anger, grief, confusion, and resignation crashing over him, he took in the reality of not knowing when he would see his partner again.

It is this same rawness that Mr Chan uses in his approach to making films, which often slant towards touching and heartfelt themes.

“Last time I want to do stupid shit but I always end up doing sad shit,” he laments.

Recently, Mr Chan posted one of his short films – All the Way to the Top – on his Instagram page for the first time, a moving tale of a brother coming to terms with his sister’s cancer.

“That one was very special to me because it’s the first proper film that I’ve ever written, produced, directed, acted in, and edited on my own. There’s a lot of pride in that,” he shares.

But while Mr Chan is only just beginning to showcase his portfolio publicly, he has always been drawn to stories.

“I love collecting them, and I love writing them down,” he reveals. And discovering film presented a platform for him to tell these stories. It allows him to capture a moment in time, “immortalising a story, a time, and a place in its entirety.”

He explains: “There’s something so daunting, yet comforting, about how finite and decisive a film is.”

And while he continues to explore the medium as a film student in Nanyang Technological University’s School of Art, Design, and Media, Mr Chan stays true to his own principle in anything he creates – it has to come from a place of “heart and authenticity”.

This motto he practises in his own life too.

The 23-year-old is unapologetically and unabashedly himself, and it shines through in the poignancy of his films. Likewise, he fully embraces his identity as a gay man, and draws from it the voices he chooses to amplify, the work that he produces, and how he expresses himself as an individual.

This Pride Month, TheHomeGround Asia sits down with Mr Chan, to uncover the ethos behind his films, how his identity informs his art, and the changes he hopes to see and enact.

(NOTE: This interview has been edited for clarity and length.)

Isaac Chan: I want to make films that are earnest and uncomfortable. But they come from a place of heart. I want them to be jam-packed with heart and authenticity, because that’s how I navigate my life. I definitely want to explore things closest to me. Being gay is a big one, being religious as well, and also just the intricacies of family relationships.

TheHomeGround Asia: Are there any films you’ve worked on thus far that you hold close to your heart?

IC: Yeah, a set of scripts that I wrote about a couple years back, in 2019. They were about the struggles of being gay and Christian. And I wrote that in the height of the True Love Is saga that was going on. Those are very honest words. And I haven’t looked at them in a while because they’re just a lot. I definitely have to look at it again, just to fine-tune it. I intend to give it legs and let it go somewhere.

THG: Where do you hope to bring this film?

IC: At the height of True Love Is, there were two very clear sides: the Christians, and the queers. They were going at it. I remember thinking I was stuck between them, and I know I’m not the only one. I remember just feeling a lot. I wish I could be fully Christian so I can just stand with them and hate the gays. Or I wish I wasn’t Christian, then I can stand with the gays, and hate [the Christians]. It’s so much easier to stand on one side and hate the other fully but when you’re a gay Christian, you’re caught in the middle. And you have to navigate being gay and Christian, which doesn’t help as both sides were being dicks about it. So I wrote that because I was feeling a lot, and I wanted to process it. The series is about this main character who’s gay and Christian but also the conversations that go on around him and without him. It’s about how everyone around him is affected, and how he is affected. It’s the idea that this is a real person, and I want to flesh that out and give it meat and bones and blood, to build this world that is my reality.

THG: What was it like growing up both gay and Christian?

IC: It was always feeling like second-class. When you’re younger, you don’t have the words to articulate it, and you kind of just see them side by side. But as you get older, your world expands, and your idea of the Church expands along with it, because you see where the Church stands in a lot of society’s fabrics.

[Homosexuals were] spoken about in a way that we love them, but we don’t want to touch them. And with True Love Is, which is basically conversion therapy, right? It’s so damaging and dangerous. When True Love Is came to my church, I remember very desperately wanting to believe that the church had changed for the better, and had started to really serve the people around it. After some time, I realised that, ‘Oh, you actually don’t care. It’s the same thing, it just looks prettier.’ That, to me, was very telling of how the church views gay people. At the end of day, it makes them feel comfortable; I accept you to the extent that I’m comfortable with.

I’ve always known that I was gay. At a young age, when you’re impressionable, you just internalise that being gay is wrong. And the rhetoric is very dangerous and insidious. It seems very loving and from a place of, ‘We love you’ and ‘You are one of us’, but there’s this difference in the way that you’re being treated.

As I grew up, then I started to see how those two tend to not come together. They’re like water and oil. So I left the church in 2019. I went through a series of things in my life that led me to find my own place with the Church. I still consider myself a Christian, I love God, but it’s more of the Church that doesn’t think I’m allowed to love God and love who I am at the same time. It was very tough when you were growing up because if all you know is Church, then as a scared Asian boy with no autonomy, you’ll be like, ‘Ah I don’t know what to do, I’ll just stay here.’ But growing up, and going through hardship, then I realised that I am forged in the fire, I have my own identity, and I didn’t need the Church any more because I felt like it was hurting me more than helping me. How they understood God was now very different from how I understood God, and for the sake of my faith, I stepped out.

But then again, the Church is not a place, the Church is its people. So I can find my own version of church in the people I keep around me.

Stepping out of church, even till now, I’ve a lot to unlearn and rewrite. But on the flip side, I do believe that growing up in church has guided the way I live my life, like my values. Kindness, authenticity, honesty, are very big to me. The [Bible] verses work when they are not used against you. They are guiding, they make sense. So, I do find that I have benefitted from the Church in the way I navigate the world.

THG: You mentioned that being gay and Christian is like oil and water. How did you reconcile those distinct identities in your own life?

IC: It’s the fact that I know my God loves me. There’s nothing he doesn’t know about me. I’ve been through a couple of experiences in my life, where He has really revealed himself to me. And I’m at a stage now where I can’t deny that God exists, or I can’t deny how good He has been. I’ll be straight-up lying. Christians always say like, you cannot oversimplify things, there are a lot more rules and stuff. But I said, ‘No, the first commandment is love. It will always be love.’ If I believe that my God loves me and I know I love Him, I’m good.

THG: On top of being a gay Christian, you’re also growing up as a homosexual man in Singapore, a conservative state. What was that like?

IC: It was interesting because Singapore is a globalised state. We are a first world country and we draw a lot of Western influences. So, you are exposed to a lot of Western ideals and Western values. I grew up alongside the rise of queer visibility. I was fortunate that when I was young, I could see a gay person on screen. So when you grow up like that, you kind of get accustomed to Western ideals but this country is still very traditional. It’s a first world country with third world beliefs. So there is a dichotomy there. You find ways to still live happily, but you can be happier.

I am tired of being treated like second-class when I give to you the same as any other person. I’ll pay my taxes, I do the Singaporean shit. I’m one of your own. I was born and raised here, but if it’s like this, I shouldn’t be able to call this a ‘home’, which is very sad. Let’s change that.

THG: What kind of changes would you like to see?

IC: I just hope that we can be open with who we love. That we don’t have to hide lah. With my partner now, I don’t really hide it. We do hold hands in public sometimes. I can do that, knowing that Singaporeans are not confrontational people, but it’s the idea of knowing that I am not supported. That is heartbreaking, and that is scary, that if it comes down to a law, I’m not even recognised. It sucks to know that. It’s almost like, you do what you want, but if we catch you, then it’s done. I just want to BTO with my boyfriend next time.

I could never picture myself living anywhere else. Never. I do believe that I will leave Singapore for a couple of years and go somewhere else and work, but Singapore is always home, I will always come back.

THG: How do you love a country that doesn’t really accept you?

IC: I love it because of what I’ve attached to it. It’s really the memories and the people. To me at least, Singapore is safe, it’s efficient, and everything is so in reach. That’s what I appreciate. But it’s also the memories and the people. They make up the country. And I know Singapore like the back of my hand; that’s a familiarity that you cannot relearn. And also, the food. It’s the teh o bing (iced tea without milk) for me. I love teh o bing, and I can’t get it anywhere else.

THG: We’ve explored how you navigated being gay as part of the Christian community, and also in Singapore. In your own personal life, was being gay something that you had to learn to embrace?

IC: Yeah, I mean when you’re growing up gay, you spend quite a sizable amount of your adolescent years trying to make sense of yourself. And when you do that, you try to take up as little space as possible, you try to keep quiet, which I could never keep quiet to be honest. But I tried. The first few times you come out, it feels great. You feel liberated, but it’s very sad. Because no one should ever feel like they are liberated from something that’s just themselves. It’s truly not a big deal that someone’s gay, so even the idea of coming out is like, why do we need that?

THG: You’re still evolving as a creative and an artist. Where would you say you are now?

IC: I think I am now finding my bearings. I’ve released a single, and I’m in film school. I feel like a baby bird leaving the nest and walking in the woods, not really flying yet. Just walking around, gathering up my little twigs to build my own little nest with my friends. It feels like I’m definitely budding. I’m very excited because in some weird foresight moments, I can see myself doing great things.

THG: What kind of impact do you hope to leave on this world, and on the people you’ve interacted with? What do you want your legacy to be?

IC: I want people to remember to always be kind, to approach everything you do with kindness, including yourself, especially yourself and the people around you in the world. I realised that there’s no bigger ‘f*** you’ to the world, than to give kindness to a place that just wants to give hate. It takes so much courage to choose to love and be good. And you only gain from being kind, good, and authentic to yourself. Another point is to be authentic, be yourself, but make sure that version of yourself is not a dick. Please be your unapologetic self, but be kind.

Also, stream my music and buy my shit. That’s my other legacy.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.