Did mandating a society to become bilingual over a generation really benefit it, or did it jeopardise our command of either languages and familial cohesion? Young Singaporeans today continue to find out.

Despite only ever communicating with my grandparents through bits and pieces of Mandarin, awkward gestures, and an unending supply of smiles, like most of my peers and through all my life, I had never thought to question our odd predicament.

Of course, we now know that a large part of our peculiar communication paradigm exists because of a bilingual policy implemented through the 60s and 70s in an effort to, broadly speaking, facilitate economic development through foreign investments and preserve our multiethnic national identity.

As a matter of fact, 85 per cent of Chinese Singaporean households were reported to have spoken solely dialects before 1979, when the Goh Report, an extensive assessment of the education system led by then-Deputy Prime Minister Goh Keng Swee, uncovered several deficiencies within the education system, chief among them an ineffective bilingualism that had led to concerning language problems: More than six in 10 students who sat for the PSLE and O-Levels from 1975 to 1977 had failed at least one of their two main languages.

The New Education System was soon founded on the recommendations of said report, and the rest is, as they say, history.

But how much of this ineffective bilingualism has actually been stamped out since the makeover, and perhaps more importantly, how effective has our bilingual policy been at improving our lives?

Say ‘no’ to dialects, but in proper English, please

I remember visiting my grandparents every weekend as a child and being in a kitchen teeming with the unrestrained conviviality that characterised my grandparents’ Teochew and Cantonese – the two dialect groups they each belong to.

Without the slightest clue as to what was being said but intrigued nonetheless, I would interrupt sheepishly in Mandarin from time to time, in hopes of validating what little grasp I had of the seemingly esoteric tongue. Although my grandparents speak some Mandarin, it has never been an adequate means of communication, and hence my relationship with them never progressed past a certain stage.

Most of my peers today seem to recall similar experiences: “We didn’t understand each other, and there wasn’t really anything we could do. Like, it’s no one’s fault. Could I have learned the language? Probably, but I was only a kid. I spoke whatever my parents spoke at home,” remarks Marcus (not his real name), a 25-year-old logistics executive, about his relationship with his grandparents.

Just like Marcus’ parents, mine never had any thoughts of me picking up dialects, and much of it, I have since found, was due to how our earlier leaders had approached language planning and policy.

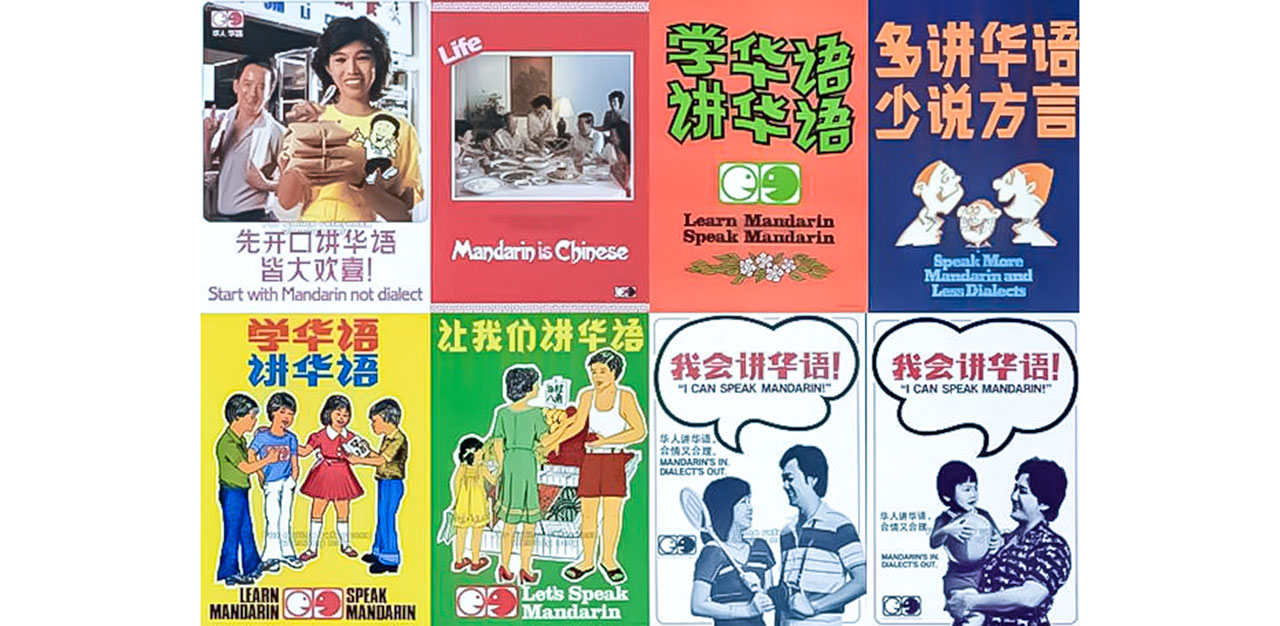

According to Lionel Wee (2009), a professor of English Language and Literature at the National University of Singapore, both the Lee Kuan Yew and Goh Chok Tong administrations, convinced that dialects were adding to the mental load of children thereby undermining their proficiency in the official languages, had embarked on a series of campaigns to rid households of dialects, putting in motion the intergenerational communication pickle we find ourselves in today.

But mysteriously left out of conversations back then, however – and what I argue is worth contemplating – was the possibility of an underdeveloped curriculum and inferior instruction.

Singapore’s underdeveloped linguistic environment

I found it fascinating when I was living in the UK that regardless of age, ethnicity, social status or occupation, the British spoke better English than practically all my peers back home in their mid-20s, elite school alumnus notwithstanding. This, despite English having been framed as the lingua franca of generations of Singaporeans.

After consoling myself, the obvious realisation emerged; our baselines are unequal, and the same conclusion would be true of comparisons between Singapore and any Anglophone society today. To put it another way, the English we grew up on, whether we were instructed in an elite or neighbourhood school, is still a far cry from the English of the Anglosphere.

This is made apparent every single time a politician, business owner, executive, or person on the street is heard speaking in the media, either fumbling to express the nuance in their speech, misusing common phrases and expressions, or in some cases, all of the above with the bonus of misrepresenting economics concepts.

Interestingly, if we take the findings of the Goh Report to mean anything, and over 60 per cent of 12- and 16-year-olds back in the 70s had indeed failed at least one of their two languages, what reasonable conclusion can we make of the general level of proficiency in society then, taking care not to forget that a segment of that cohort would logically go on to teach the next?

Could this be why students in as late as the early 2000s and 2010s, like myself and everyone in my social circles, continue to recount anecdotes of MOE-trained English teachers endorsing characteristics of the language we then later came to realise were misguided? Very likely so.

Alas, the inconvenient truth is that our bold attempt to grapple with not one new language but two – neither of which have spent enough time within our society and institutional framework for mastery to be evenly distributed across the population – has ensured a relatively mediocre command of either language in the layperson. The clearly observable fact that the average Singaporean’s English is not prized in the UK today, nor their Mandarin in China and Bahasa Melayu in Malaysia, should lay to rest any doubts.

Considering that language within societies takes generations to reach any level of sophistication – in homogeneous environments at that – it is entirely natural for us to be in such a predicament today. We have not been brought up on a fully developed language, and that’s because we do not yet have one.

Not fitting in, at home

It should be reasonable by now to posit that without the idiosyncratic bilingual policy of previous administrations, Singapore’s communication paradigm would look vastly different today. Apart from what has already been argued, familial and, by extension, intergenerational cohesion might have radically diverged from our current reality if, for instance, citizens then had a say in which languages they wanted for their children.

It is my belief that harmony at home largely stems from shared values, traditions, ways of and ideas about life. By the same token, few would argue against the notion that one’s language also shapes one’s worldview. This is perhaps why members of a family who speak a different language eventually see their paradigms diverge.

“I don’t really tell my parents much these days because they wouldn’t understand most of it. It’s kinda pointless,” Alex (not her real name) laments. A second-year communications student in university, her experiences growing up in a fairly conservative Chinese family who had picked English to raise her with – they made English the language spoken at home after she was born – echoes mine.

She explains: “By the time I was in secondary school, everything I was consuming was in English, and mostly from outside of Singapore. By then, the Chinese content my family was watching appeared quite boring to me. I just couldn’t relate.”

What Alex had described was more than just a communication gap. As we build our perceptions of reality around the language and media we come into contact with each day, we drift further and further away from family members with different realities, eventually losing the ability to recognise each other’s. This might explain the tension that some of us experience at home, sometimes from the way in which a family member approaches a problem, other times from simply how they choose to live, but always due to a misalignment of beliefs and values.

Some families may manage these drifts better by cultivating shared values through family activities, but what happens when a family lacks the time or inclination?

A relevant island is a prosperous island

Most people today will insist that the bilingual policy saved Singapore’s economy, and that this is revisionist arrogance fuelled by some version of hindsight bias.

“But we had to do it. We had to speak English to be relevant to the world,” says Megan (not her real name). “How else would we have competed? For investment, for commerce?”

As a 24-year-old graduate student, she believes that Singapore would have flopped if not for a bilingual policy that prioritised the language left behind by our colonial masters, and she is not alone in this view. Of the countless friends with whom I have had discussions about this, virtually none disagreed with the Government’s policy.

But surely it is mere conjecture to argue that without the adoption of English, Singapore would not have made similar strides. Those who doubt this only have to look over to Hong Kong, our cousin who operates an economy fairly similar to ours and who has achieved comparable economic success within a similar time frame without forcing its citizens’ tongues.

Despite never having to abandon their native tongue, the predominantly Chinese society was still able to connect with the world and establish themselves internationally. Hong Kong films have never had to be in English or Mandarin to attract an international audience, and Hong Kongers have never been coerced through policy to change the language they spoke at home, with their elders, or in their communities. While it is undeniable that segments of Hong Kong society have always spoken English to varying degrees, that was the extent of their language policy. Citizens chose for themselves the level of penetration the language had in their lives, and that was it.

Although being under British rule until the late-90s meant that the city had some privileges, GDP growth after the handover to China kept its trajectory for the most part, and the simple fact that virtually every generation of Hong Kongers since their colonisation has operated primarily in their mother tongue should induce one to re-evaluate their assumptions here.

Ultimately, they made it by being themselves, and the nation’s triumph in modern history should be seen as the antithesis of Singapore’s long-held edict that our economic edge rested on our ability to speak “good English”.

Nevertheless, it remains a mystery if the bilingual trap has truly inflicted more harm than good to Singaporean society and culture. It is, however, worth taking some time to appreciate this curious feature of our linguistic history, pending any lessons it might reveal for the future.

Chester Tan is a freelance writer, aspiring photojournalist, and communications student in his final year of university.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.