With the dismissal of Tan Boon Lee from Ngee Ann Polytechnic in Singapore weighing on the national conversation around standing up to errant educators, while shedding light on the mental toll of racist acts, what do parents think about measures being taken by the Polytechnic and the Ministry of Education to tackle racism and other harmful behaviours and attitudes of staff in schools? TheHomeGround finds out.

The decision to dismiss senior lecturer Tan Boon Lee from Ngee Ann Polytechnic (NP) over a case of serious misconduct came more than a week after he was reported to have made racist and Islamaphobic remarks in two separate instances, four years’ apart.

Police investigations into both incidents are ongoing.

Nurul Fatimah Iskandar, 22, the NP alumna who blew the whistle on Mr Tan’s allegedly racially and religiously insensitive behaviour in a 2017 programming class she was in, has been a key figure in the Polytechnic’s internal investigations.

“Ngee Ann released a press statement which reads as a typical signal that all necessary actions have been taken and that the case has been closed,” Ms Nurul tells TheHomeGround Asia when asked for her response to the NP announcement on 17 June.

“But my intention was never to fight against one lecturer or one institution. There are so many more changes that need to be made to our education system in order to safeguard and protect our students,” she adds.

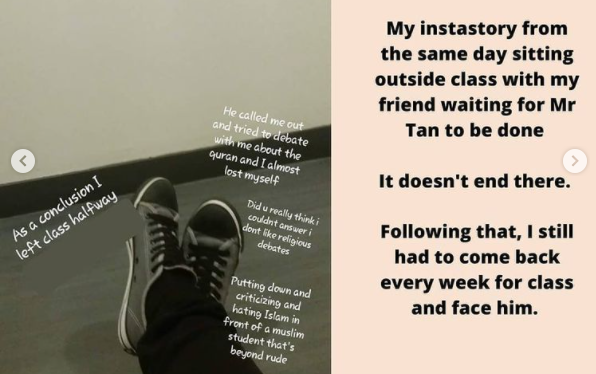

In her 9 June Instagram post, Ms Nurul recounted an episode in Mr Tan’s class when he had initiated a discourse on Islam between himself, an ethnic Chinese Senior Lecturer in his 50s, and a classroom of mostly 17-year-old engineering students.

The Polytechnic’s statement detailed that it had charged Mr Tan for a “serious breach” of the institution’s staff code of conduct and would terminate his service: “The disciplinary action meted out against the staff in question reflects our commitment to provide a safe, inclusive and respectful environment for our campus community.”

It added that it will now “make all feedback channels for students more accessible and visible on its website”, and that it would be “reviewing its internal feedback monitoring processes to identify and resolve gaps.”

In the same vein, the Ministry of Education (MOE) has said that any form of racism is unacceptable and has no place in local schools, according to this report on 17 June. It also encouraged students and staff who experience racism in schools to flag it to their institutions immediately for investigations to be conducted, and that “those engaging in racist acts will be counselled and disciplined”.

MOE further announced that all schools will have a peer support structure in place by the end of this year, which would enable students to support one another and learn how to speak up for peers when necessary.

In the aftermath of the Tan Boon Lee saga, Ms Nurul describes the mental health ordeal that she endured, which was buttressed by strangers gaslighting her experience online and the investigation process with NP, her former school.

“When I decided to share my experience, I could not have imagined that it would gain so much traction overnight. Yet, it is the aftermath of that initial post that has taken up all of my time and energy in the last week (week beginning 14 June),” she tells TheHomeGround Asia. “It has also placed a heavy weight on my shoulders and taken a serious toll on my mental health.”

Amid the cynical and snide remarks that made it into her inbox and onto her social media post were assertions by commenters that the Polytechnic “was going to bring you down”, “twist your words to protect their image”, and “just want to close your case and move on.”

While Ms Nurul had initially defended the Polytechnic, she reveals that she was quickly disillusioned when investigations began. “Ngee Ann proved them right,” she claims, exasperated.

According to Ms Nurul, NP spending most of the investigations cross-examining her story, instead of discussing policy reforms, which was her “main intention”, had contributed greatly to her stress.

“Here’s the best part… Ngee Ann gave me their counsellor’s number when we met…but when I told the counsellor that because of Ngee Ann’s gaslighting and stuff, my mental health has relapsed into self harming, because of all the self-doubt they put into my head… the[ir] counsellor suggested for me to see an external counsellor,” she elaborates.

“This also caused my condition to worsen as I had to worry about money for treatment, use a lot of energy to e-mail and call everyone [I needed to see in the process], and spend time repeating my situation every time I got passed on to someone else,” Ms Nurul adds.

As her mental health continued to deteriorate, Ms Nurul stopped assisting in the investigations, citing the need for family and friends – some general practitioners and counsellors – to monitor her for self-harm and suicidal thoughts.

Pointing to the possibility that the Polytechnic’s counsellor may not have had the relevant training to advise her, Ms Nurul says that the Student Support team at her current university, the National University of Singapore (NUS), “swooped in like a hero” to offer the help she had sorely needed.

As of 19 June, Ms Nurul has been in touch with NUS for her mental health concerns.

Standing up to bad teachers requires more than courage

TheHomeGround Asia reached out to a number of parents for their thoughts on the outcome of these two episodes involving Mr Tan. While many declined to be interviewed, those who spoke viewed the dismissal favourably. But they also remain cynical about the idea of standing up to unsavoury teachers in Singapore’s educational institutions.

Beyond acts of self-preservation and calling out injustice, they think that the implications associated with whistleblowing are far more complex than is understood.

“I’m not surprised that there are educators behaving in ways they shouldn’t be… schools don’t make it easy for students to complain, and students also fear,” says Kim (not her real name), whose son is in secondary school.

She recounts the time when she had to weigh the pros and cons of lodging a formal complaint against her son’s teacher in primary school.

“I hesitated to complain about the teacher in my son’s class because if I were to complain and give my name and reveal who my son is, when they speak to the teacher they will reveal these things… my son would be in her clutches,” she says, alluding to her lack of confidence that complainants’ identities would be protected, and in the professionalism of teachers.

“The teacher can very easily give you a low grade just because they don’t like your face, you know?,” she remarks.

Lorraine Chua-Raja Shagaran, whose son is of mixed-ethnicities, says she agrees that confidentiality cannot be absolute: “It’s hard to have complete confidentiality… even with your peers in school… it’s very hard to control that.”

In some sense, the sentiment that Kim and Mrs Chua-Raja Shagaran have expressed is analogous to that of students like Ms Nurul, back in 2017.

“I was on a scholarship and my grades depended on him,” points out Ms Nurul, highlighting the same fear and uncertainty that parents like Kim feel when contemplating speaking out against educators.

Another perception that surfaced in conversations with parents was that varying levels of professionalism exist not just among educators but in institutions too.

Civil servant Raj (not his real name), who is a father of two interracial children, doubts that the education system is consistent in managing complaints and feedback.

“Most teachers, principals, whoever is in charge… they might not care… They don’t care until something very bad happens… That’s how it works in the civil sector,” he claims. “It’s the same thing with the poly… they are only doing this now because they got knocked on the head.”

When asked if he would still encourage his daughters to use a feedback and support system if a similar one to NP was implemented in their schools, Raj says: “Of course. The new measures are good, but different schools will still have different ways of handling [complaints about teachers].”

Kim appears to agree with Raj. “How well it works will depend largely on how the institutions manage it. Do they take the complaints seriously and put effort into the investigation? If they do, then it may work. If they just ignore or do cursory checks into the complaints, then it won’t work,” she declares.

But are some schools better placed than others to succeed?

Kim thinks so. “It depends on the culture and mindset of the institutions’ senior management,” she posits. “It took over four years and multiple complaints from different parents for a single bad teacher in my son’s school to be transferred out.”

She also claims that teachers will only be dealt with when they have accumulated years of negative feedback.

These suspicions closely mirror what students like Ms Nurul have encountered in tertiary institutions only recently.

“I’ve had friends complain to Ngee Ann, and they can testify that Ngee Ann has a habit of a) dragging the issue for so long that it dies and never gets resolved; or b) the issue was turned onto them, like when students complain about the curriculum, or something,” she explains.

“There’s never been any of my friends who brought up a complaint and had Ngee Ann resolve it in a way the students had wished.”

Moving forward

An external panel might be necessary to examine complaints, argues Raj: “Otherwise it won’t work.”

He believes that only a non-partisan body employed to manage and process complaints or feedback can be trusted to handle cases without bias: “It’s very difficult for the school to be objective in such things.”

Likewise, Mrs Chua-Raja Shagaran thinks that educational institutions should have a dedicated committee for the managing of complaints of educator misconduct, and for students to seek recourse.

She also emphasises the need for a feedback and support infrastructure that helps students in difficult situations muster the courage to stand up for themselves, much like the one that NP assures it will improve.

Another way to prevent unsuitable educators from slipping into the system, suggests Mrs Chua-Raja Shagaran, is to make the recruitment process more stringent and sophisticated.

Ultimately, though, empowering students to stand up for themselves in school starts at home. “The confidence to stand up for yourself also comes from upbringing. Parents have to tell their kids that they can and must stand up to injustice no matter who the culprit is,” she says.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.