Ah Meng was the Singapore Zoo’s brightest star.

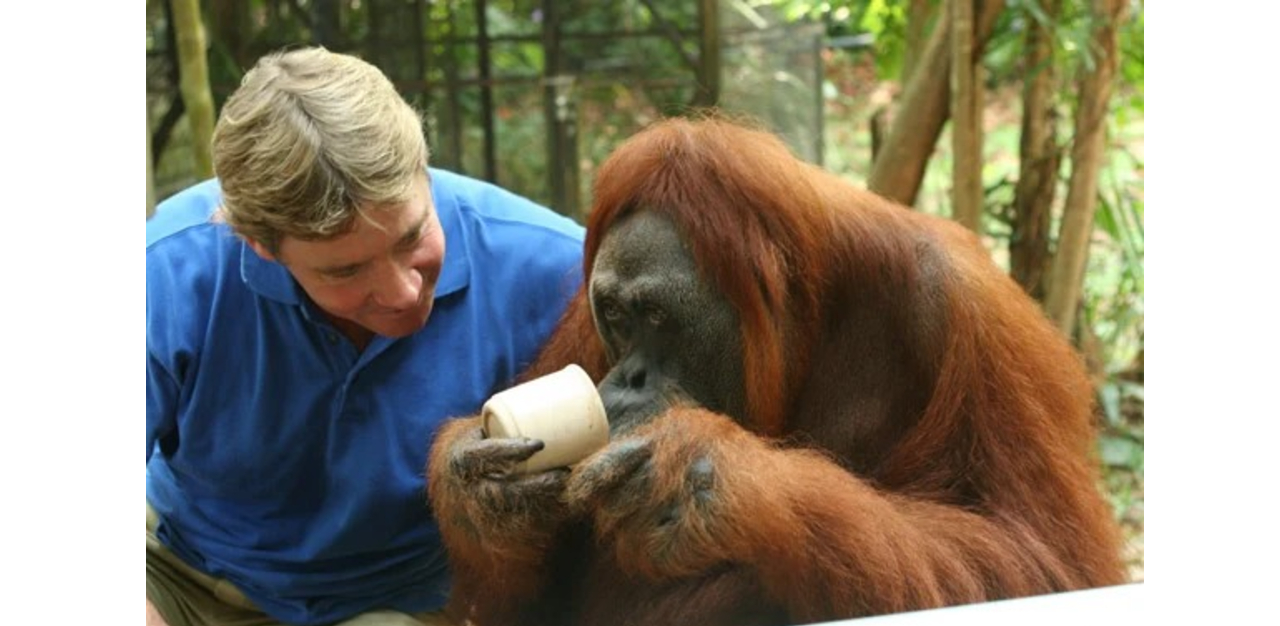

The late Steve Irwin, Australia’s wildlife expert and conservationist said she was the most famous ape in the world, having “done more for Orangutan conservation than any other animal”, when he visited the zoo in 2004.

But at the same time, Ah Meng was a prima donna.

She had the makings of a mega-star and the personality to pull that off and became a legend, but a real “pain in the back” was how ex-CEO and executive director of Wildlife Reserves Singapore (1981-2002), Bernard Harrison describes the grand dame.

Ah Meng apparently held a longstanding grudge against Mr Harrison.

Speaking to TheHomeground Asia from his home in Bali, Mr Harrison recalls that he and then Chairman, Dr Ong Swee Law, would take a weekly tram tour around the Zoo, and would always ask for Ah Meng to come along.

“She would sit between us and Dr Ong would spoil her with Horlicks tablets. This went on for years, until one day, Dr Ong said he didn’t want her tagging along anymore,” he says.

“So, whenever we drove around the zoo, she would watch us as we went past on the tram, sitting and brooding in her enclosure. After that, I would only take photos if Sam, [her favourite keeper], was around. I think if I was left alone with her, she would have taken me apart!” he adds.

The makings of an icon

Born in Sumatra, Indonesia, Ah Meng arrived at the zoo in 1971 after being removed from a family who kept her as an illegal pet.

“In the late 60s, with Singapore being a bustling trading port, there were many illegal wildlife trading activities. And so you could easily buy an orangutan, and many people in Singapore actually kept one in their backyard,” recalls Mr Harrison.

This practice ended when the government started enforcing the Wild Animals and Birds Act with substantial financial penalties, and there was an influx of 20 odd young orangutans surrendered to the zoo. Among them was Ah Meng.

However, Ah Meng was not the first pick for stardom. Another young female named Susie was the default choice for VIP photo ops, but “she unfortunately died in childbirth after about two or three years”.

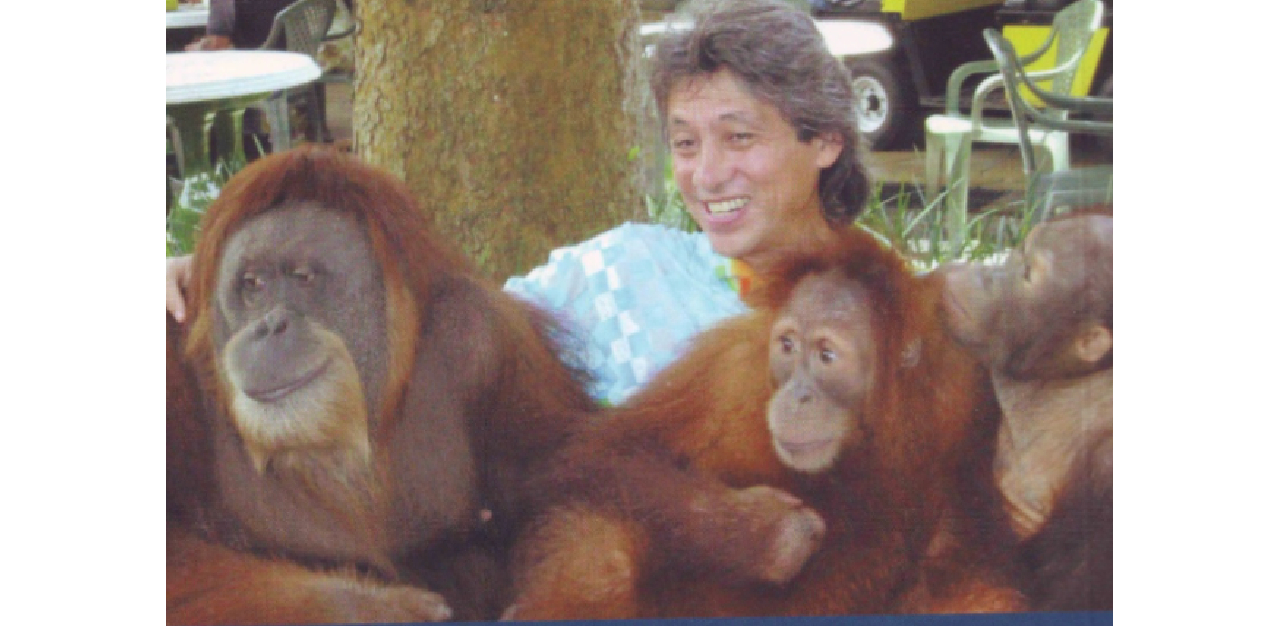

“Ah Meng was sort of groomed to take over. She was good looking all around, though she had a little bit of a sour face, compared to Susie. She didn’t slouch much, like many other orangutans did. Very anthropomorphic, but that was the kind of stuff we were looking for at the time,” Mr Harrision says.

As it turned out, Ah Meng became the Singapore Zoological Gardens’ Unique Selling Proposition (USP) when it first started in 1973 and helped Harrison and his team break through the stigma many Asian zoos had to the international public.

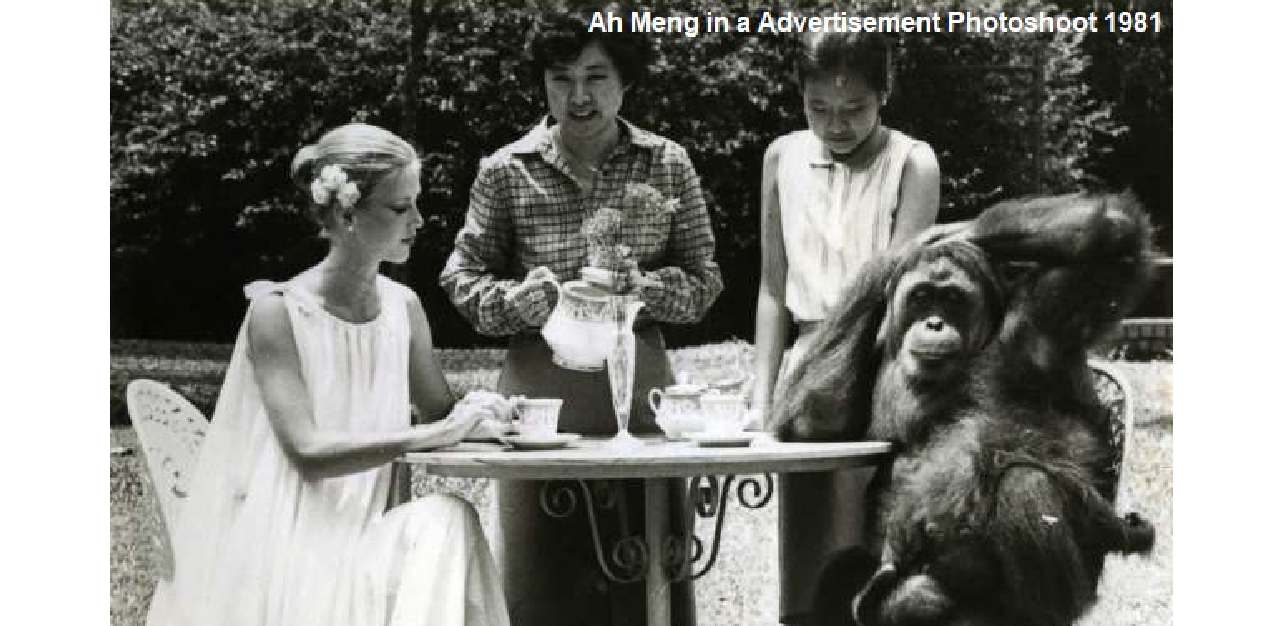

Breakfast with Ah Meng, launched in 1982, was the answer. Instead of regular close-up shots of animals, the zoo now had a picture of an orangutan and a beautiful lady having breakfast, and that “put us on the world map and pushed us to be ranked as one of the top 10 best zoos in the world,” Mr Harrison says.

Ah Meng’s fame rose alongside the Singapore Zoo’s, catalysed by encounters with many celebrities of the era. She was driven to the Raffles Hotel to meet Michael Jackson and Elizabeth Taylor during their stay in town.

Other notable figures upon whom she graced her presence include Prince Philip and “Tarzan” actress Bo Derek, who, on several occasions, would drive straight from the airport to the zoo, unannounced, just to see Ah Meng and then leave. Harrison even recalls that she was charging the media a modelling fee of $5000 for every half-hour, “bringing in heaps of conservation funding for the zoo”.

The special treatment did not help the diva’s behaviour. Once, Ah Meng spent three days up in a tree and at another time, she threw a jealousy tantrum. Otherwise, Ah Meng was a “gentle old girl”.

A new age for zoos

In a previous interview with her favourite keeper Alagappasamy or Sam for short, he said: “When [tourists] accidentally touched her in the wrong place[s], she wouldn’t get angry. She would just turn around and look at me as if to say, ‘Sam, what’s happening? […] What are you doing about it?’ She’s a big ape and has the strength of five. If she [were to] change her mind, she could give you a big bite. But she didn’t.”

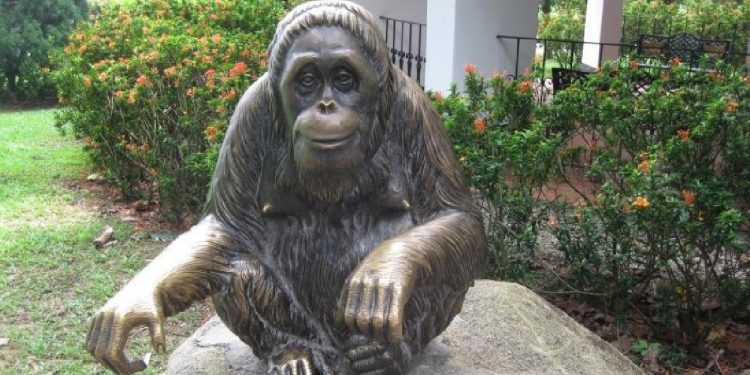

Her death on 8 February 2008 was collectively grieved by the zoo, the nation and even the world. About 4,000 people attended her funeral.

Her death also informally marked a new era for the zoo.

“We were a zoo that was new to the world, unrecognised and privy to the preconceived notion that Asian zoos were typically a horrible affair. We were just trying to create a tourist attraction, so we just did a lot of media and publicity stunts,” says Mr Harrison.

Today, Mr Harrison, who is an independent zoo consultant, believes that the days of intense PR for animal superstars are over. “The zoo has changed and matured […] alongside the people’s changing sophistication, and these days we’re much more into delivering conservation messages instead of iconic individuals… It’s obviously different, but not necessarily bad. It’s just working with the times,” he says.

The struggle for zoos to become undisputed institutions of conservation has been a longstanding one, and Mr Harrison believes that only in recent years have they begun to be taken seriously by the global scientific community.

“While about 90 per cent of zoos in the world deserve to be shut down, a lot more zoos nowadays are getting involved in conservation. They’re not only breeding in captivity (ex-situ), but also in-situ (in the wild),” he says. “They’re also forming alliances with national parks, supporting them financially and cross-fertilising each other.”

Wildlife Reserves Singapore, for example, has been continuously funding regional conservation and research projects dedicated to the protection of threatened species in their native habitats in the region. Ah Meng was one of the success stories for ex-situ (captive) breeding, leaving behind a legacy of two sons, two daughters, and six grandchildren. She was particularly known for being an excellent mother, and even adopted babies whose mothers had died — which as far as Mr Harrison knew, was unprecedented in the zoo world.

The fate of wild orangutans

Even in death, Ah Meng continues to represent how much work there is left to be done for orangutans in the wild, whose habitats in Northern Sumatra are being destroyed by deforestation to make way for the palm oil industry.

The number of orangutans have halved over the past century as over 80 per cent of their habitat in the lowland forests have been cleared. Rachel Koh, Forest Conservation Manager of World Wide Fund for Nature Singapore (WWF-Singapore) says: “Sea level rise due to climate change also affects them as they largely dwell in lowland habitats.”

Despite the success of captive breeding of these apes, the IUCN Red List still considers them critically endangered, only a notch above extinction in the wild. Since the 1970s, WWF has been working on Orangutan conservation using a multi-pronged approach.

“We seek to conserve their habitats by undertaking forest landscape restoration, as well as support indigenous communities by promoting sustainable practices that reduce human-wildlife conflict,” she says. “Through awareness and stakeholder engagement, we want to promote sustainable landscape management and peaceful coexistence with wildlife.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.