Can you choose your race? This may be a thorny issue with many, but in the land of table-top role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons (D&D), choosing your race is how you begin.

You can pick among a handful of options: an elf, a dwarf, a half-orc.

Step into the shoes of a mountain dwarf, and you will earn racial advantages in strength and constitution. Or play a half-orc, and beware the savage fury that runs in your veins, inclining you towards acts of barbarism.

Then, when you’re done making your character choice, grab your sword and find a quest. Fight a dragon and discover some treasures, then return to a tavern to drink ale and boast of your exploits to the comely barmaid: a satisfying sojourn through a classic fantasy adventure.

The official worlds of D&D, set in the Forgotten Realms, are replete with fantasy tropes such as these, heavily inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Say “fantasy” and what comes to mind are knights and princesses, castles and magic swords – all set in a vague European-style medieval world exemplified in shows such as Game of Thrones and The Witcher.

But “classic fantasy” isn’t neutral, and fantasy worlds are reflections of real-world cultures. Predominantly, our ideas of fantasy are derived from Judeo-Western origins that carry with it social and cultural baggage that we often take for granted when consuming fantasy media.

The cultural tropes range from how (until very recently) women are expected to be damsels and not dragon-slayers; to how the racial hierarchy of savagery and order in fantasy is mapped to the colour of one’s skin.

In short: fair elf good, dark orc bad.

In Singapore, though, players of D&D are turning the world’s most popular table-top role-playing game on its head by challenging what fantasy can look like. They brew their own imaginary worlds while still using the basic game mechanics.

Fantasy can now look like a futuristic solarpunk Asia post-climate collapse, where people wear actual beehives in their hair, or even have a sword-swinging goblin, who uses a heavy Singlish accent when she speaks, living among them.

The habit of whiteness

In a book entitled Race and Popular Fantasy Literature: Habits of Whiteness, academic Helen Young writes about the “habit of whiteness” in fantasy, where fantasy is set in a “monochrome Middle Ages” that imagines a Western Europe devoid of black, brown or Asian people.

Theoretically, while fantasy should be a realm where anything is possible, Young says many white consumers and players have a stake in preserving an escape from a more complex social reality. These players argue that multiracialism in fantasy would be historically inaccurate to the Medieval times in which the game world is set.

If we take the argument of being historically accurate seriously, then it fails. Medieval scholars have long noted the lively presence of non-white individuals in the European Middle Ages.

Furthermore, the demand for historical accuracy in a fictional genre is itself questionable. Writer Emma Vossen notes in a scholarly article titled There and Back Again: Tolkien, Gamers, and the Remediation of Exclusion through Fantasy Media that when non-white characters are introduced into fantasy RPGs, it is seen as a politically motivated decision, made to pander to the demands of a “woke” crowd.

But, as author Chuck Wendig puts it, “if we can have werewolves, why can’t we have black people?”

D&D was shaped by similar influences. The game was created in the American Midwest in the 1970s by Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax, who were in turn inspired by predominant narrative blueprints for mainstream Anglocentric fantasy, such as J.R.R Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

This carried with it troubling notions about the racial savagery of orcs, a reflection of antiblack ideas which associate irrefutable brutishness to a race by virtue of biological inheritance.

D&D’s drow race — a group of dark-skinned elves who live underground, worship the spider goddess Lolth and are evil by nature — also surfaces as an uncomfortable example of the racism inherent in D&D’s imaginary worlds.

Genetic determinism is sharpened by D&D’s game mechanics. Until recent revisions introduced in one of D&D’s latest official source books, Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything, picking a race also meant picking gameplay statistics, locking players into racial stereotypes.

Asia in official D&D

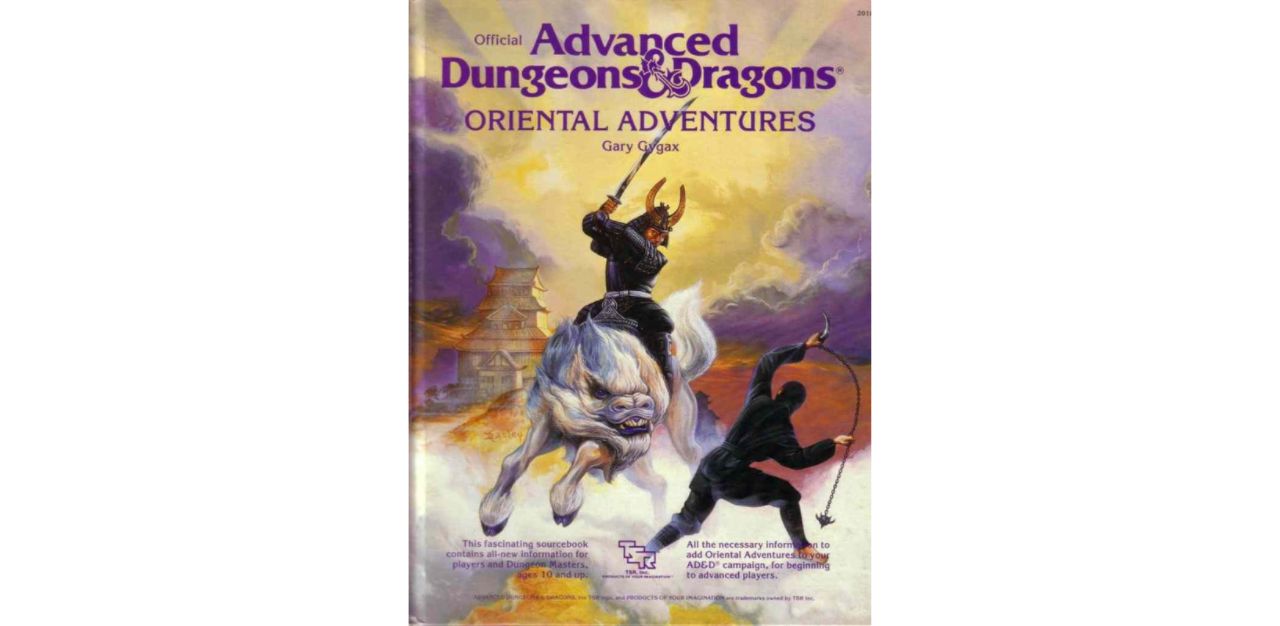

The dominant appearance of Asia in D&D has been through Oriental Adventures, an official supplement released in 1985 as an addition to the existing canon. Drawing mainly from East Asian worlds, Oriental Adventures introduced a non-western feudal society named Kara-Tur, with new playable classes such as ninjas and samurai, martial arts fighting styles, and an honour system, where characters can lose or gain prestige, depending on whether they adhere to specific codes of honour.

While commercially successful and critically lauded at the time, Oriental Adventures has been soundly critiqued by scholars who consider it an exemplification of Orientalism – a reduction of diverse and distinct Asian cultures to a set of problematic stereotypes.

There have been calls to make Oriental Adventures unavailable for sale online due to its outdated depiction of Asian cultures, and D&D has included a sensitivity disclaimer to online marketplaces where the supplement is still being sold.

D&D is aware of its shortcomings and has directly addressed its treatment of orcs, drow, and the Romani-inspired Vistani peoples in the release of a recent diversity statement, which notes, among other matters, that diversity readers are being employed to correct stereotypical portrayals of particular races in D&D.

But questions still remain.

Globally, the idea of “Asia” in the D&D realm is still a Western image of Asia – fixed mostly in East Asian mysticism that features monks, nunchucks, and kungfu.

So how does Southeast Asia, specifically Singapore, deal with the fantasy worlds of Asian D&D? What do we even consider “Asian”, and how do we reflect real-world cultures in the realm of fantasy?

“Kamsia lu”: In the world of Urtu, is this Hokkien, or Goblin?

On Monday nights, somewhere in this world exists Yrsa, a goblin fighter/barbarian with a pronounced Singaporean accent. The Goblin language as spoken by Yrsa sounds strangely similar to Hokkien, and Yrsa herself has a blunt motherliness that is both immensely likeable and culturally recognisable.

Yrsa is played by actress Sheena Chan, and she can be found on a Twitch stream called The 4th Culture (T4C), a Singaporean D&D game set in the non-Eurocentric fantasy world of Urtu. For those accustomed to hearing Anglo accents on D&D streams – a Scottish accent for dwarves; something vaguely British for nobility – it can be jarring to hear Ms. Chan speak for the first time.

Yrsa lives in a world created by Dungeon Master Ramji Venkateswaran, and T4C tells the story of four individuals who have been conscripted by the Namandan Union to escort a Namandan emissary and negotiator to the Sivalai Kingdom – and their continued journey under the ground, through the jungles, and towards adventure as they traverse the wider world of Urtu.

“The idea of a magic ring or a sacred sword, the concept of Valkyries – everything in D&D derives from Arthurian, Germanic or Nordic myths,” observes Mr. Ramji.

Even when Mr. Ramji encountered D&D games set in Asian worlds, he noticed that these games were set in a vaguely fictional China – a make-belief Middle Kingdom that failed to reflect the depth and breadth of Asia, and often riddled with exclusionary stereotypes.

Born in India, Mr. Ramji spent some time as a child in Zambia, moved to the United Kingdom when he was a youth, and then spent his 30s in New York. He then migrated to Singapore eight years ago.

The fluidity of his migration history has influenced Mr. Ramji’s creation of Urtu, and his ears are pricked for what he calls “deep patterns” in Asian stories that indicate the rich cross-fertilisation and syncretism of the region’s cultures.

“As someone who grew up an avid reader in a Hindu family, I hear Buddhist stories from Chinese cultures and recognise the same narratives in very old Vedic tales,” he says. “There are deep, deep patterns that run through a lot of these stories even though they look radically different on the surface.”

The emergence of Asia in Urtu follows this same syncretic logic. To create this world, Mr. Ramji invited T4C’s players to sit together with him and play a game called Microscope, a collaborative world-building game. They spent nine hours creating the history and mythology of Urtu.

Then Mr. Ramji took the stories that the players had made and, as he describes it, “put them through a meat grinder.” Similar to how Asian myths are worn and changed by time and travel, Mr. Ramji mashed up the stories so that players would dimly recognise particular names or histories when they emerged in the game and have an emotional reaction to them.

“It’s like when you see a boat named the ‘Titanic’ and you have that feeling of immediate recognition,” Mr. Ramji explains. “Sometimes players will come across something they created in the world and they’re like ‘oh, no. So that’s what happened to my story.’”

The impulse to mix and match the stories comes from Mr. Ramji’s desire to ensure that Urtu remains a syncretic world. “It’s meant to be a little bit of this, a little bit of that, blended very aggressively. We play in Singapore and we are a very Singapore-based group, and part of that means that we reach into our backgrounds and tell a story distinctively our own, but also make them a collective tale.”

However, Mr. Ramji has no interest in being didactic about the Asian world he has made, which is full of shards of Asian references – prata and porridge served for breakfast; intan serving as divine gems; and yokai, devas, and nagas who live alongside Urtu’s peoples, rather than above them in an untouchable pantheon of gods.

“D&D isn’t a history lecture,” he says. “There’s something magical when things are mundane. Like, it’s not special that there are temples or shrines: it’s just another thing between you and where you’re going. Or it’s not special that everyone in this world is a mongrel, and that very few characters are ‘pure-blooded’. It’s reflective of our world, where we are defined by generation upon generation of migration.”

An Asian world also does not only mean Asian references, but narratives that resonate with local cultures. Mr. Ramji muses on how many of the players’ stories are coming-of-age tales. Kaman, played by Edward Choy, is a sea elf devoted to the god Eijnar who realises that he does not like who he is and has to grow into who he wants to be. Barra, a flashy young bard played by Jo Tan, learns to mature beyond an initial narcissism.

“Our coming-of-age tales, our concepts of becoming an adult are very different. It doesn’t necessarily mean moving out of home or the end of filial duty,” says Mr. Ramji. “I guess expanding the definition of what an ‘Asian tale’ is is an interesting possibility of what The 4th Culture could be.”

Solarpunk Asia: Evertown, everlasting

Somewhere in the future exists the utopia of Evertown, a permaculture co-op community built on the coastal lands that have survived the rising sea levels of climate collapse in Asia. Evertown is a world of abundance: there is no need to work for money, jellyfish farms float in the shallows, and technology is powered by the twin forces of magic and sustainable energy.

This is the setting of Sunk Coast, a D&D one-shot set in a futuristic world of an imagined, aggregated Asia, as created by Ruchika Goel, Bobby Satya Ramadhan and Māia Berryman-Kamp.

“We wanted to make a world that was post climate collapse, but still built on the idea of abundance, where people can be happy,” says Ruchika Goel, the Dungeon Master and writer behind the game. “It’s not a world where you’re scraping metal forever. It’s solar-punk, not scrap-punk.”

South and Southeast Asian inspiration glimmers through the world of Sunk Coast. The world of Evertown boasts the edible kitchen gardens so common in Asia, and its inhabitants share a thriving repair-over-replace ethos – reflective, Ms. Goel says, of Asian cultures where people have long built products for longevity and not to throw away.

An element of D&D woven into this worldbuilding is that almost everyone in Evertown knows the Mending cantrip, a basic D&D spell that allows cracks or tears in everyday objects to be magically fixed.

Evertown handles waste disposal for large, complex items through the creation of a Rage Room. Ms. Goel was inspired by an old North Indian system of door-to-door peddlers, called kabadi, who buy paper and metal waste from people’s homes and take them back to warehouses to break down, repurpose, reuse, and sell.

“It’s a major childhood memory for me as I diligently collected all my paper and cardboard to give away on the weekend,” Ms. Goel says. “Random and disparate ideas from our lived experience and travels helped us make up a lot of systems in Evertown – for violent crime mediation, for electricity, for commerce, and the idea of work.”

Illustrator and game designer Bobby Satya Ramadhan adds that Evertown’s variegated forest landscape was inspired by Kebun Raya Bogor, a botanical garden in Bogor, Indonesia, located near where Mr. Satyar grew up. A walk through the garden one day brought him face-to-face with a line of red ants busily carrying food down a small branch of a tree – an image which flourished into another element of worldbuilding in Evertown.

“The forest area of Evertown is so big and intertwined with trees, it’s hard for them to carry things around by themselves, right?” says Mr. Satyar. “So let’s make these ants big and give them a job to deliver people’s stuff from A to B. It’s an Ant Postal Service!”

The architecture of some parts of Evertown drew inspiration from the conical-roofed Honai houses in Papua, Indonesia, which Mr. Satyar modified by adding some technological elements. “Our goal is to take fewer references from outside Asia so that it can feel like this game is for us and by us,” Mr. Satyar says. “Yet we still give the sense of inclusiveness in the game, like how the characters there are so different in colour, shape, and ideology, and yet they can still live together in harmony.”

Ms. Goel adds that the diversity of Evertown was cast through modifying D&D races – for example, the people living in the desert in Evertown are more ‘dwarvish’ than others, in that their physiques and clothes are modified to match the hardy and tough exterior needed to survive in desert conditions.

“In the end, Evertonians are evolved versions of people today,” Ms. Goel says. “In a world where you can throw cantrips around and be half-genie, it felt moot to call anyone ‘human’. But they’re all still people, on a spectrum of humanoid shapes, with culture, with faults, with dreams.”

The imagination of this aggregated Asia and its implications in terms of representation is something that Ms. Goel considered very thoroughly as they worked through the details with their teammates.

While they wanted to create a world inspired by the richness of Asian culture, they also wanted to ensure that they did not make a monolithic version of Asia that might become exoticised when viewed with a foreign eye.

“We had to put in a lot of really strong thinking in terms of accents and clothing, especially when characters say something that doesn’t paint them in the nicest light,” Ms. Goel explains. “How did we mark out our villains, and how were they connected to the cultures they are from? Gender, race, and ethnicity were really important, especially when I played characters with features I couldn’t speak to from my own identities.”

Climate collapse scenarios often verge on the apocalyptic, but the decision to create Evertown from a place of hope rather than of despair was a deliberate choice. Ms. Goel wanted to make a world without the limitation of scarcity, founded on joy, and free from the trauma of colonisation, to see what emerged from those beginnings. The driving impulse was to give characters possibility, not constraint.

“We wanted to create a world that supports your actions, to have as much potential as possible,” Ms. Goel says. “There’s a strand of memory and remembering where we came from and how we messed up the world. It’s never forgotten or unacknowledged. In Evertown, we keep our traumas and histories in mind. But the real world we live in now is already encumbered by endless faultlines. Why add more, in fiction too? What does that do for us?”

Remaking Western fantasy in homebrewed Asian D&D worlds is not a matter of simple “flavour”, to put it in terms of a common D&D expression for customising one’s character background and culture.

As Mr. Ramji says, Asia, as imagined, is the product of remix and transformation, of finding common patterns across various contexts and recognising the syncretism that underlies so many Asian stories. For Ms. Goel, the desire was to create an Asia where scarcity was no longer a limiting factor, and to see how that inspired people to imagine a future founded on community and collaboration.

“Instead of a singular Asian theme to build towards, we had more pressing Asian themes to undo,” Ms. Goel says. “And then we let the players create the narrative of the game in its playing instead.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.