How many more migrant workers in Singapore have to die or be injured before their safety becomes the only factor to consider when deciding whether or not to ban the practice of transporting them at the back of lorries? TheHomeGround Asia gathered a panel of six individuals to hash out the recurring hurdles that continue to prevent this issue from being resolved after more than a decade. Could conversation, and not just opinions presented in silos, be what is needed to take this issue forward? Read on to find out what a guest worker-poet-community leader, advocates for guest workers’ rights, an opposition party parliamentarian and someone with decades of industry insight say must be done to move this issue along.

All five panellists unanimously agree that safety for migrant workers is “paramount” and that this should drive discussions and decisions on whether the practice of transporting workers at the back of lorries should continue to be allowed with further enhancing of safety measures, or banned, in Singapore.

The panel discussion was held on 15 May in response to three recent accidents involving lorries carrying workers in the past month, which killed two workers and injured 37 others.

Moderated by former Nominated Member of Parliament and founder of A Good Space, Anthea Ong, panellists included: Opposition Member of Parliament (Hougang SMC) from the Workers’ Party Dennis Tan; Founder of One Bag, One Book and award-winning poet Zakir Hossain Khokan, a Bangladeshi who works in the construction industry; Desiree Leong, Casework Manager from the Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics; Reverend Samuel Gift Stephen, Lead Director of the Alliance of Guest Workers Outreach; and Junior Schoeman, Managing Director of Innate Discovery Talent.

At the start of the panel, each guest laid out their position on the matter. Most were adamant that the practice must be outlawed.

“We cannot continue such a behaviour from a business perspective, simply because it is unsafe…there is no protection for the individual in there [rear deck of lorry],” says Mr Schoeman resolutely, who has more than 30 years managerial experience in the construction and mining sectors. He adds that in talking about this “complex” issue, one has to start with “first principles”. This means the debate should centre around humans; their safety and dignity, as well as how “we treat them”.

“It’s not always a matter of money. Humans have this particular ability, when faced with a challenge to come up with a necessary solution… especially when everybody has an opportunity to talk and participate without getting emotional,” he remarks.

Mr Tan agrees that “dignity” is important: “If you regard the safety of anybody at the back of the lorry as paramount, more important than making money, more important than business, than rushing to fulfil the business engagement, then we have to give priority to this safety issue… Safety must be the starting point.”

Safety is also a priority for Reverend Stephen but he also says this varies in degree depending on whose perspective, whether worker, public, or the employer’s.

While concurring that human life is key, Ms Leong also notes one other factor: “We should keep in mind that the law should apply to everyone equally. There should be… equal safety standards that apply to everyone. There shouldn’t be a special carve out that disproportionately affects migrant workers.”

Reflecting many voices in the migrant worker community, Mr Zakir says the shared opinion is that it is not safe to carry migrant workers at the back of lorries and that it must be banned. He states, “It has been proven to kill not only workers, but [indirectly] their families too.* It is not safe this is visible, there’s no need to explain more. It is really frustrating for me and my community that we keep highlighting these things… we come to 2021 still we are talking about this.”

(*Guest workers are often the sole breadwinners of their families. When they are killed their families are the surviving casualties of the tragedy; not only losing a husband, father and/or son, but also the means of an income to survive.)

The issue of migrant workers being transported to and from work in the carriage deck of lorries has been part of the national conversation in Singapore for more than 10 years. It often resurfaces in the public consciousness after an accident.

As far back as 2008, a Workgroup was convened by the Ministry of Manpower and the Land Transport Authority to review the safety of the practice, consulting with stakeholders, including industry groups and safety experts. According to Senior Minister of State for Transport Amy Khor, who spoke in Parliament on 10 May, the Workgroup’s recommendations “aimed to protect not only the workers’ safety, but also their livelihoods”, which she noted was a difficult challenge.

Aside from making changes to regulations between 2009 and 2015 to enhance safety, and implementing harsher penalties for non-compliance, legislating an all-out ban has so far been ruled out. Common reasons the Government trots out have mostly revolved around its impact on businesses, such as higher costs and operational difficulties that could lead to productivity loss.

So while on one hand the Government has acknowledged that it takes the safety and well-being of all workers seriously, it has to date hesitated to disallow the practice, even though, as Dr Khor says, “from a road safety perspective, it would be ideal for lorries not to carry any passengers in their rear decks.”

For instance, the Workgroup found in 2009 “no strong justification” to merit such a ruling given its impact on businesses. Fast forward to 2021 and the rhetoric has not changed much: “Regulatory changes at this time will cause even more acute pain to the industry,” says Dr Khor, “given that the industry is being severely affected by Covid-19.”

But like an ear-worm that refuses to be silenced, calls to end this practice continues to gain traction.

Advocacy groups and rights activists have reiterated a long-held stance that workers should not be ferried, unprotected (without seatbelts), like cattle; that lorries are for carrying goods not passengers; and that Singapore as a developed country has a duty to end a morally indefensible practice.

A long-time advocate for the ban of lorries transporting workers, Stephanie Chok, wrote an article in 2010 that quotes a worker as saying, “When I first arrived at Changi Airport, I was so impressed. Then a goods vehicle came to pick us up. I was shocked and felt very ill-at-ease, why is this company sending a goods vehicle to pick us up?” Another worker shared, “The first time I had to travel by lorry, I felt quite shocked and embarrassed.”

Dr Chok also manages Humans Aren’t Cargo, a campaign blog (started in 2009) that has logged all the media-published reports and letters about this topic, the earliest is a letter from 1990. The letter ends, “Surely, an alternative to squatting on a lorry would be useful in providing a better image of Singapore vis-a-vis its workers’ welfare.” Does this sound familiar? Granted workers no longer squat; they sit in a space measuring four square feet.

More recently, in April last year, she was reported to have asked on a Facebook post how the Singapore Government has been spending the large amount of foreign worker levy (FWL) collected over the years, and whether it might be used to help pay for the “cost” of caring for the welfare and well-being of low-wage guest workers. Based on the range of levy rates between S$300 and S$950 in the construction sector, Dr Chok estimates that the minimum amount collected comes close to about S$72 million a year. For official figures, in 2012, according to then Acting Minister for Manpower Tan Chuan-Jin, in a written answer to Parliament, the Government had collected S$2.5 billion in FWL in FY2011.

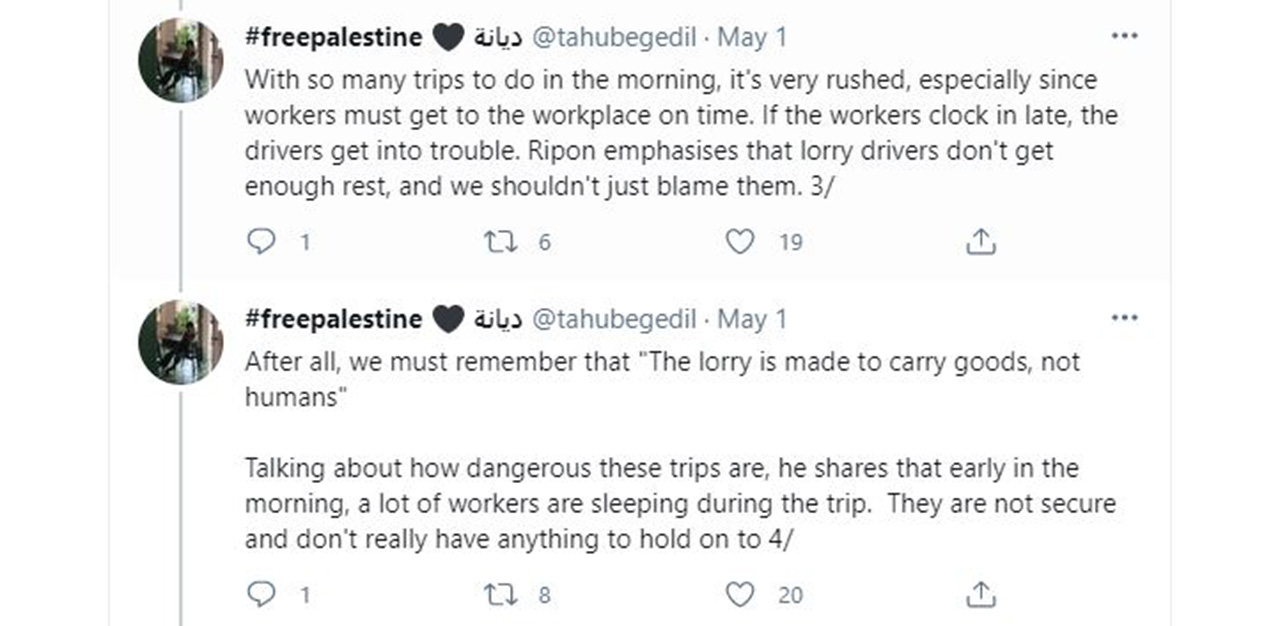

There has been a groundswell of support to find alternative forms of transport that are safer, with an online petition to mandate that workers are driven in buses or vans garnering more than 21,000 signatures. Many workers have also spoken up explaining why they want this practice stopped, unequivocally. Ripon Chowdhury, who works as a quality controller in a shipyard, says that lorry drivers are often the first ones to be blamed when accidents occur, and calls for greater understanding of their work conditions. He had shared his thoughts during an open meeting organised by Sg Climate Rally on 1 May to talk about workers’ rights.

Migrant rights NGO HOME also highlighted in its Labour Day statement that drivers have told them they are on the road 13 to 16 hours a day, ferrying their colleagues for all work and essential errands. It called on the Road Traffic Act exception that allows for this practice “to be removed”.

On 10 and 11 May, the topic made its way back into Parliament, where questions were posed as to why the practice continues, how the Government and relevant agencies plan to further improve safety, and several Members of Parliament proposed solutions.

One of the suggestions by several parties has been to commission under-utilised buses.

On 21 May, Melvin Yong, Assistant Secretary-General of Singapore’s labour movement, the National Trades Union Congress, visited bus operator ComfortDelGro Bus to find out how to tap on idle buses during off-peak periods. He notes on a Facebook post that this might be a “safer option” for employers “to transport their workers, in place of using lorries.”

Despite so much ink and saliva being spilled on this issue, nagging questions weigh on many minds: If the safety of workers is widely acknowledged as a priority by those with decision-making powers, why are costs to businesses still trumping calls to ban the practice? Why are those put most at risk due to this practice – the workers – not at the forefront of decisions being made that continue to put their lives at risk? What is the value placed on workers’ lives versus those of business interests and considerations?

TheHomeGround Asia shares six key takeaways from the panel discussion that attempt to answer these questions.

(NOTE: The transcript has been edited for length and clarity. A full audio version of the panel discussion will be shared soon, please look out for it.)

On why the practice still continues despite growing calls for it to be banned

Reverend Samuel Gift Stephen: I was in a dorm with 119 guys and I asked them over lunch, ‘How do you feel about traveling on lorries?’. And every one of them in their lorries said, ‘I don’t care how I travel, as long as I get to the dorm on time.’… If you ask me why do companies still practise this, I put it down to three words. Number one, it’s cost. Number two is convenience. Number three is common practice. For cost basically, for larger companies, getting buses is a norm. It’s all incorporated within their cost perspective. But for small, medium companies, that is where they struggle, because any cost involved would trickle down to the worker somehow; to the welfare of the workers, even to cutting back some of the perks… Convenience, basically, lorries are meant to bring goods. But at the same time, if you’re bringing goods to a worksite, for most companies, they will think bringing the workers on the lorry will also save time and save money. Number three, common practice, since most people are doing it, why can’t I do it? That’s the thought that most companies have… the best scenario would be that someone pays for the buses, and every guest worker goes on the bus. But, ‘who?’, that’s the question.

Desiree Leong: The very basic reason why this is still going on is because it’s allowed. It’s allowed under the law. And that’s the honest and brutal truth of it. As for the point that (Reverend) Sam made that workers have said that it doesn’t matter as long as I get there on time. What this highlights is: it’s not to say that safety is not important to workers. Why are they in such a hurry to get back to the dormitory or to the worksite? Because their working hours are too long. And because if they didn’t get back to the dormitory faster, every minute that they spend on the train, for example, instead of being ferried by the lorry will eat into their rest time. What it does show is that there are bigger issues, rather than simply the transport issue. As for addressing the concern that businesses have about costs, the fact is that business operations should follow or adapt themselves to the law and to basic human rights, and not the other way around. And we do know that the authorities have not had qualms about imposing certain painful and abrupt adjustments in the business-costs and operating-costs environment when it is deemed that it’s necessary to do so.

Junior Schoeman: The problem that we sit in is that we have operational silos. You’ve got the owners’ perspective, contractors’ perspective, and employees’ perspective, each one is selling a service to the other. So when… looking at this issue in a holistic manner, it becomes problematic. When government starts getting involved and gets over-prescriptive, and starts trying to provide a solution, where we don’t allow the market to provide its own solution, and find its own little road, we start having problems. And we start having people over-explaining and over-defending, instead of keeping a neutral position. Instead of saying, from a government perspective, these are minimum requirements that we have; it’s for you, as a contract owner, as a developer, to sort out your pricing structures, how you address it… Maybe we are reactive. And we are not allowing the market forces to dictate and do itself the honesty of fixing itself up.

Dennis Tan: If safety is really an issue. If we consider ourselves as a first world country. If we value human life, and no discrimination as to what kind of human life, regardless of race, regardless of profession, regardless of vocation, then we need to look in the long term. We need to ask ourselves, ‘As a country, where do we wish to draw the line?’ Do we continue to draw the line here and say, ‘Well, you know, for certain kinds of workers, because of business costs reasons we will make do with that?’ Yes, business costs are an issue, especially now in Covid. But pre-Covid, post financial crisis, when the economy was doing well, what was being done to improve on this situation? Was effort being studied by the Government on how to help businesses to make this leap, if they need to, to stop using this opium? And it’s not too late. I’m open-minded in the sense that the solution may not really be immediately to change the regulation. But we need to, perhaps give ourselves… a time target to work towards. In the meantime, have a good study on the additional costs that is required… I hope the Government will look into the costing involved, especially to help the smaller companies… Yes, they may have difficulty surviving, but we need to look at how to help these companies, and overall to bring the standard up on the carriage of workers.

On dealing with the “acute pain” to industry if transport rules were changed now, as noted by Senior Minister of State for Transport Amy Khor in Parliament

Ms Leong: This has been discussed for many years, and no progress has been made in the good times for the construction and marine and process industries. And now when times are tough, there is a hue and cry that we shouldn’t be imposing further acute pain. In fact, I would take the opposite perspective. I would say the time of a crisis is exactly the time for re-evaluating fundamental assumptions. At this moment of crisis, the Government has since last year stepped in with a lot of bailouts and support. Is this not the time for such changes to be made and to be reconsidered? During and after the circuit breaker, our public servants overcame incredible logistical challenges to deal with the situation in so many different respects. We at HOME may not have agreed with the underlying value judgments of those logistical feats, but we have to respect that these things were done… redeploying hotels and vacant school sites to decant and house migrant workers; that is one example. So I don’t think it’s a matter of shortage of resources, of technical ability to deal with the issue. We should seize this moment when people have been more sensitised to the problem, to the plight of migrant workers, to reconsider some of the basic things that we have just been taking for granted for the past decade and a half…So I don’t think that it’s necessarily addressing the concern to say that it’s too sudden, or it’s too painful to impose that kind of cost, when there is an adequate justification to do so. In this case, the justification is human life and the safety of the workers.

Zakir Hossain Khokan: If you say the cost higher, or if you put one excuse that Covid situation, how is the past 13 years? We hope that the conversation will be overcome very soon, because we want healthy practice in the community. You cannot make excuse in this Covid situation. We are talking for long run. We are not talking for one year or two year. We have to focus on that area and who are coming here to do business; they have to improve this business… how they can negotiate or they can talk with government how they can adjust their levy or whatever. This they can settle with the Government.

On other countries like Canada, Thailand and the United States still allowing for travel in the back of lorries

(NOTE: The moderator Ms Ong highlights a number of points when posing this question. The first is that in these three countries the person travelling in the cargo bed of lorries or pickup trucks chooses to do so, or not. Secondly, not all states within the US allow for people to travel at the back of pickup trucks, many have outlawed this practice. This is the same in various provinces in Canada. Thirdly, the Thai Government had initially banned the common practice of travelling at the back of pickup trucks in 2017, but then relented after feedback from the public and changed it to a maximum of six passengers. Those who travel at the back of pickup trucks do so to get to work or to visit their hometowns, because it is a cheap form of transport.)

Mr Schoeman: From a perspective of justifying because somebody else is doing it, it’s like, because my brother’s stealing, I’m allowed to steal. It’s very simple. So if we’re going to use that type of approach, then everybody should be stealing… so we cannot justify… If we’re going to reference other countries, then we should also reference Australia and all these other places where it’s totally banned.

Mr Zakir: Singapore has to make example for other and other will follow Singapore… I was very surprised why this example come that other country is following… Everyone understand as a human being that safety is very primary thing for everyone. Everyone. And carry migrant workers on lorry this is not safe. This is very common. So answer is there. We have to… draw one line that Singapore make a standard level for safety for migrant workers. This is the level: ‘Hey, other country follow me.’

On why the transport issue is a symptom of underlying factors

Ms Leong: One of the root issues is that we are not properly valuing the workers and allocating the human resources adequately. In the particular context of Singapore, you put goods and humans in the same lorry. Why? Because to be very frank to the industry, to employers, and to us as a society, we’re treating migrant workers the same as just goods. Why? Because, our work pass system basically treats migrant workers as completely disposable. Some companies just cycle through them, very high turnover rate, there is very little incentive to retain workers. And therefore, there is very little or almost no incentive to develop them, to assess whether working conditions have optimised them as a person, optimised them as a worker and optimise them for our industry.

On what they would like to see in the short term

Mr Tan: We should immediately start looking at what are these cost issues, and see how the Government can help make things easier for those who are struggling – the SMEs. In the meantime, we should look further into how the driving conditions can be improved until it’s completely banned. I’m not sure that seatbelts are completely off [the table]. Perhaps in certain circumstances it can be used. We can look at, for example, limiting the numbers. Sometimes it’s quite alarming to see the number of workers in one little delivery truck. Driver fatigue is an issue. So this goes to improving the working hours for our workers, and also this issue about driver qualification. It’s been mentioned in Parliament and elsewhere that rules were changed to let workers who have a Class 3 driving license to qualify as a driver, but is that really enough? Shouldn’t we have better vocational training for example, especially better safety awareness, better safety training… These are just mitigation factors because ultimately we have to decide whether we want to allow this to continue. Is it right for us as a nation?

Mr Schoeman: There’s most probably going to be ineffective to put an immediate legislation in there. But we got to have… definitive actions that need to be taken by set time. And we don’t have to go out there and say to them, you’ve got one year, whatever pushback. Covid might be with us for next 10 years. So that’s not an excuse… The immediate solution that we’re looking at is, drivers, what can we do? We can very rapidly identify those who are most at risk, who should not be driving. That can be done; it takes about 45 minutes to do that. We can weed out those who are inappropriately able to work under stress, or have these necessary cognitive processes to make those decisions… Let’s allow the market to start sorting itself out. I feel we are a bit of a nanny state, where every time somebody suffers, government wants to step in. I think it’s time that we let the children grow up a bit.

Reverend Stephen: I use this word ‘guest workers’… And we are the hosts. As a host, dignity is one. Number two is appreciation. And as our brother mentioned, like waiting three hours for transport to come. How do you show appreciation by making them wait, you don’t honour their time. And I think these simple things can be weaved into our guest worker culture, into the entire ecosystem… What I would do is to highlight the companies that have decided to use bussing, incentivise them, honour them. Somehow it catches on… doing good is contagious. Instead of just legislating everything, it’s encouraging a culture, because if it takes legislation to make something right, then I don’t think that our culture is going anywhere… It’s bringing to light the good practices of some of the companies and encouraging others to follow suit.

Ms Leong: In the immediate short term, I think the rational and sober thing to do would be to have a transparent assessment and study of what the actual costs are. What are the actual pain points? And who is actually suffering? And how much? So that, you know, we have a clear basis on which to move forward. And I have to say, at this point that I totally agree with Zakir that there are some things which do not need to be studied or researched, it’s very obvious that it’s, for example, not safe. But since there is so much outcry about pain, that should be laid out clearly exactly what is this pain… This creates an impetus for the Government to take the lead, at least initially, in view of the public health situation, and the regulations that have been imposed; to create infrastructure and systems for this transport of workers that hopefully, in the medium term, the industry leaders can then take over. Unfortunately, it’s the case that the Government still takes the lead on a lot of such changes in Singapore. All these costs and logistical challenges of transporting workers [in the current regulatory regime restricting workers’ movements] have fallen on employers. And it is understandable that they’ve had difficulties with having to provide transport for the workers absolutely everywhere, for every single errand. So that is actually where the Government can step in, at least in the immediate short term. And hopefully, when that infrastructure has been put in place, slowly, the reins can be handed over to the industry leaders, SCAL (Singapore Contractors Association Ltd), the big players like the main contractors, shipyard management, all those process industries on Jurong Island and at Tuas. That’s where workers actually need the lorries, because public transport is not feasible.

Mr Zakir: In short time, I want to see from the policymaker… they have to declare LTA or whoever… that the lorry system will be banned very soon. They can set time by two month, by three month, by four month. This lorry system, we’re going to ban, I want to see this. And in this time, they can do adjustment of levy or whatever, how they can support the company, and company can… work with the government policy, they can negotiate each other. But as a migrant worker, I want to see this declaration or this announced that lorry is going to ban from this date for carry the workers… No, we don’t want to see morning or afternoon the scenery that migrant workers is behind the lorry… This can go to the museum. This cannot be seen on the road in Singapore.

On what they would like to see in the longer term

Mr Zakir: A lot of things we need to do in community, like change views about migrant workers, this is very important… This type of view needs to change that migrant workers not only doing this ‘3D’ (difficult, dirty and dangerous) type of work, they’re also doing wonderful work. You can find migrant workers’ books also publishing in Singapore, and they are talking in that book about transport (in MD Sharif Uddin’s Stranger to My World). The migrant community have writer, singer, TEDx speaker, a lot of things… When a society change the view about migrant workers in Singapore, a lot of things, positively one by one, would change.

Ms Leong: We hope that that can lead up to, in the medium term, a very firm legislative position that will not be discriminatory, and that will, as Zakir said, be government taking the lead, with the law taking the lead to set the environment for businesses to operate in, the moral boundaries.

Mr Schoeman: The other issue which is very pertinent is they’re not migrant workers. They’re not migrating, we are importing them. So terminology around people need to be changed. So we have an issue in Singapore that we don’t have locals want to enter into this industry. So if we set standards, which is universal, irrelevant of where you come from, it gives us better opportunity to make it a more inclusive industry. The industry by peer pressure is exclusive, where the inclusion of a local citizen only in the senior or engineering type of roles. They are not that open. There’s a stigma around it. And that needs to be improved. And if… we start focusing on the key potentials of people, rather than focusing on who he is, what he does, where he comes from, we will have out of there the solution that we’re looking for.

Mr Tan: We should set a target for ourselves and work towards it. And it should be a stage implementation… taking in consideration all the factors, dealing with costs. And today, particularly instructive for me… you all [panellists] have pointed out something very important, which is that what we are talking about is a part of the symptom, right? So the problem, may I put in another way, is how we look at our employees. How we look at our workers. How do we value them? And this brings us back again to my issue about safety. If we think that safety is paramount for everyone, for our workers, then that should guide our motivation as to what we should do from here, setting our targets and looking at the issues.