I still remember the first time I read an Arthur Yap poem. My junior college literature department had graciously prepared us a compendium for the unseen poetry segment in our A-Level exams. Ironically, we were analysing An Afternoon Nap, a poem that scrutinises the Singaporean penchant to glorify academic achievements as the ultimate goal in the life of a student.

More often than not, most of us would have had our first brush with Sing Lit in the classroom, either as a compulsory text or a highly recommended read from our English teachers. A popular title that comes up is Sing to the Dawn, with many Singaporeans having either read, watched, or heard of the short story or its animated remake. Interestingly, its author, Minfong Ho, actually identifies as a Chinese-American writer, although she has some roots and personal experiences living here briefly.

Perhaps it is stories like Ho’s that have compelled the Sing Lit steering committee to rebrand the movement from #BuySingLit to the recently inaugurated Sing Lit: Read Our World in December last year.

The volta: from commodities to creatives

When we think of Sing Lit, our minds may conjure up stories about kampung life, HDB flats, MRTs or hawker centres—any quintessentially Singaporean landmark to convey a story that predominantly recounts Singapore life. We think of notions like racial harmony and academic rigour or postcolonial resistance, and epidemic kiasu-ness forming major themes. We think of snippets of Singlish being inserted, sometimes clunkily and in a contrived manner that well, to be honest, makes us cringe. Sometimes.

But perhaps we are filling our heads with what we think we know as Sing Lit. Perhaps there are novels and poems that are more heavy-handed in telling the Singapore story but there are many other creative works that have moved past it.

Essentially, it is this pivotal shift in narratives that is captured in Sing Lit’s fresh brand of paint this year. While Sing Lit can — and probably still does — constitute the aspects mentioned earlier, the rebranding reminds us that there is much more to what it entails.

Sing Lit: Read Our World moves the readers’ gaze from simply purchasing a book by a local author to recognising the multiplicity of the Sing Lit universe; a Sing Lit multiverse if you will.

As a literature graduate, one of the first things I remember learning was how all-encompassing the term “literature” is. How it can refer not only to fiction and poetry but also to comics, autobiography, essays, theatre productions, films and TV shows, podcasts, and radio dramas. The rebranding highlights an important component of literature, Singaporean or not, that art is not only for artists or art connoisseurs.

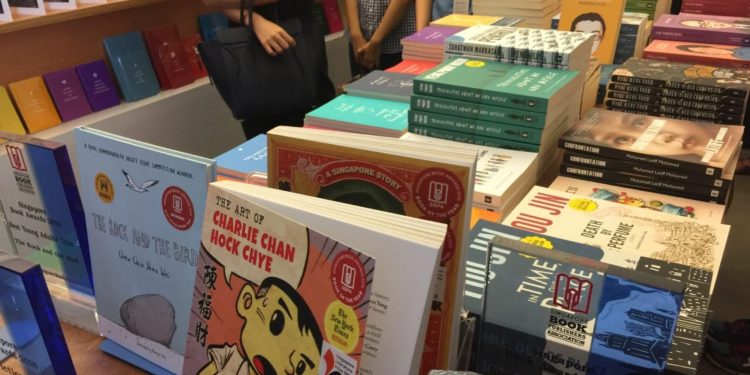

By this new logic, Sing Lit spans films like Crazy Rich Asians to graphic novels like The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. The world of Sing Lit has become as limitless as Marvel’s Cinematic Universe.

On top of that, the shift marks a new age in supporting Sing Lit.

For author and copyeditor Carolyn Oei, removing “buy” from the branding was an important move as “we could do less with the commodification of Sing Lit, or anything, really”.

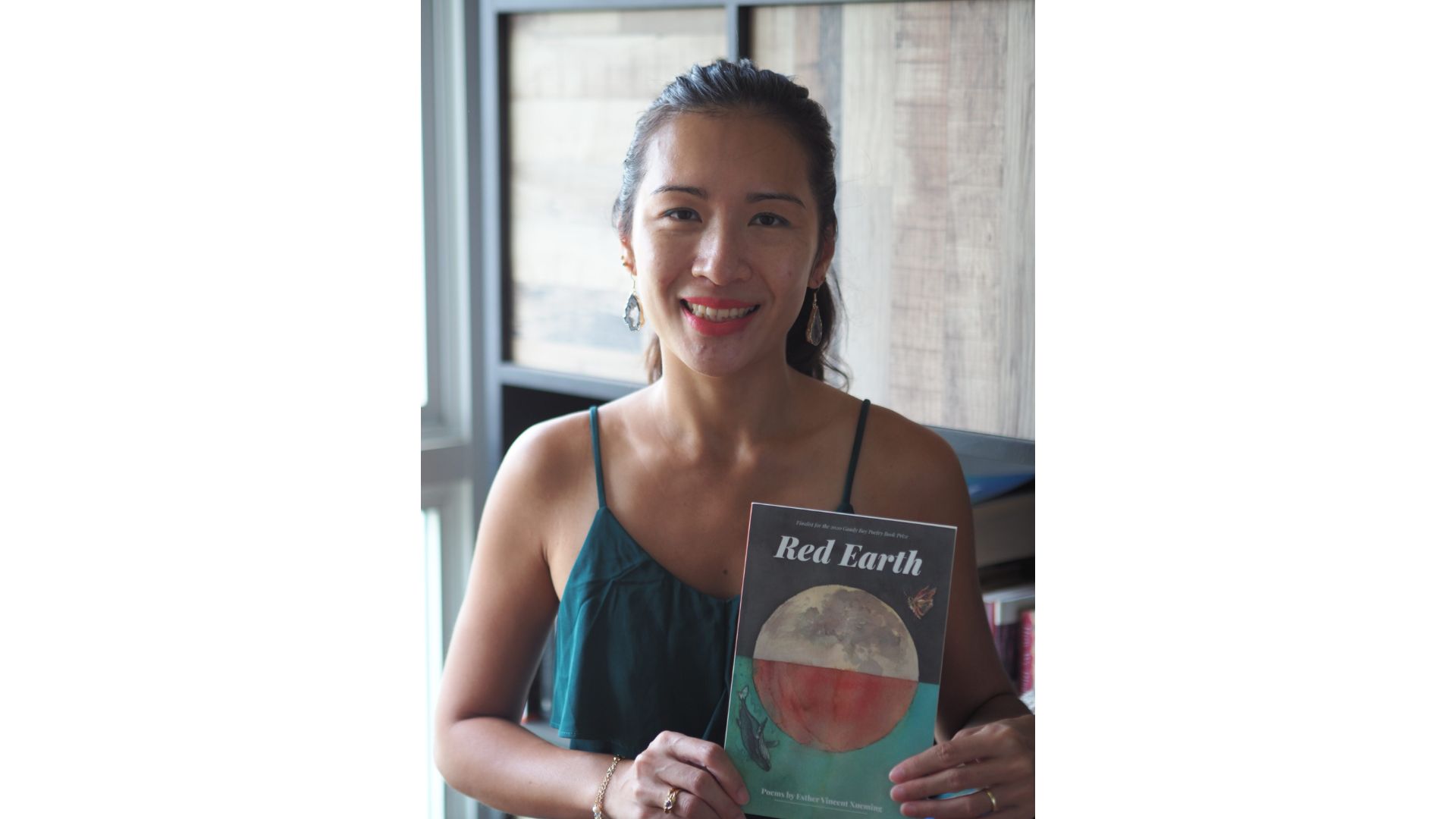

Similarly, author of Red Earth and editor-in-chief and founder of The Tiger Moth Review Esther Vincent Xueming also notes how both approaches were necessary for specific parts of the Sing Lit journey.

“Initially, the best way to show support for artists is to buy their work — and it still is. Now, we can move from financially supporting artists (which we take as a given) to nurturing certain dispositions and being aware of our significance or insignificance within the grander scheme of things,” she said.

Both writers concurred how the focus has gravitated towards bringing the Sing Lit community together as a united and healthy ecosystem of writers and creatives in the country. There’s a more apparent and concerted effort in doing so such that the writer is located within a larger web of relations within the local writing community.

Ms Oei summed it up best as she emphasised the vast definition of Sing Lit so long as it is “written by someone who has a deep relationship or is sympathetic with Singapore, regardless of the subject of the work”.

Breaking the art wall

“When you like something very intensely, it unlocks an impulse in you to make something very much like it.”

These were the words that opened my interviews for this article. Scriptwriter and producer Roshan Singh’s personality fills the Zoom screen, an impressive feat considering that there were four of us all compartmentalised into our boxes in the gallery view of the virtual meeting room. The minute the 27-year-old starts speaking, his eager baritone voice instantly tells you why he’d go on to make a radio drama.

“After you experience a meaningful work of storytelling, you reach a point where you can’t help but try. You think to yourself, if a human being made this, surely I, as a fellow human, could make something similar,” he said.

It’s this slice of wonderment that eventually pulled Mr Singh out of being a mere consumer of film, television, and radio into a creator himself. The founder of Andas Productions, an audio fiction company, always considered himself a science student throughout his school life. But when he heard the main theme for Howl’s Moving Castle, he found himself banging on a piano trying to replicate the song till he finally got it.

It’s not an unfamiliar tale. I find myself thinking of how my obsession with Taylor Swift as a 13-year-old compelled me to buy a guitar and start strumming away in pursuit of jamming along to the blue-eyed country star’s music.

However, Mr Singh only entered the foray of writing much later in his first year in university through a 24-hour scriptwriting competition. He found himself deriving more meaning from the eight hours he put into writing scripts all night to the eight hours he normally spent in labs doing statistical coding and conducting interviews. He recalled thinking, “If I could only work like these eight hours for the rest of my life, then surely it would be a good life.”

All along, Mr Singh bought into the narrative of art as something only certain people were capable of making. That one has to have an innate tendency and/or competency towards making a literary work of any kind. And by extension, as a science kid, it never occurred to him that creating a play was within his realm of possibility. Not before the scriptwriting competition at least.

“I think sometimes we just need to realise how thin the barrier actually is between having an idea and being able to finish something. Finishing the play and seeing it materialise in such a short period of time showed both how difficult and how easy it is. It made my ideas tangible. It made it real,” he said.

The competition illuminated the magical and surreal experience of creating: how one could spend the whole day working on something and wake up to see it come to life the next day.

The keepers of the craft

There’s no doubt in Mr Singh’s mind that Singapore is a place for world-class storytelling and talent. Yet, it seems like Singapore itself is the only one who fails to recognise it.

“We exist in a world where storytelling has been democratised,” said the creator of Temujin: An Audio Drama.

In a world where the difference between a thousand-dollar and ten-dollar podcast is muffled in sound waves, it’s worth asking ourselves why it is still so difficult to enter the literary scene in Singapore. The barriers to entry for art seem almost inconceivable in an age where one should be able to distribute their works at a click on their phone.

Ms Vincent, for one, had been entangled in poetry far before she eventually published her first collection, Red Earth late last year. She had her poems published in various journals and magazines before, but was only able to devote time, space and energy into realising a full manuscript under the guidance of Singapore Australian poet Boey Kim Cheng at the Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

She divulged how “the scene in Singapore is not friendly to chapbook publishing because it’s not perceived by publishers as economical”.

Upon rejecting her chapbook, a publisher told her that she should work on a full-length manuscript instead of trying to get her chapbook published. “The implication was that I wasn’t ready for publication since I didn’t have enough poems to make up a full-length manuscript.”

Looking back, she is grateful for their comment and can appreciate its wisdom as it motivated her to pursue her writing through a creative writing graduate programme dedicated to her craft.

Yet, perhaps Ms Vincent’s experience elucidates our nation’s archaic perception of viewing literary works with a transactional end in mind.

Perhaps there is an overlap between drawing distinctions between science and art as an audience as well as picking out the best-sellers from a flurry of literary pitches. And for all we know, it starts from rejecting, even on a subconscious level, poetry or any literary work as “a luxury we cannot afford”, as famously uttered by our late Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew.

Whether it is the luxury of affording the S$20 Sing Lit book from Kinokuniya or the luxury of purchasing a pricey ticket to a local play, literature and art have had a history of being shunned as an impractical route for Singaporeans to undertake.

However, Sing Lit’s new trajectory seems to indicate the relinquishing of these preconceived stereotypes and misconceptions.

A new act with fresh leads

“Read Our World” connotes not only a shift from the commodification of books but a thrust towards a love for reading and a love for literature that can be nurtured throughout the country. We are no longer distancing art from artists but recognising that they come from the same place—that a community of bookworms begets its own community of writers. Just see any fanfiction website as proof.

But more significantly, we’re allowing local literature to transcend the borders of our country. We are no longer limiting Sing Lit to a certain name or geography.

And in this bid to extend the definitions and readership of Sing Lit, all three writers proved how it simply starts by making room for one another in our local literary community. Where other countries may suffer the fate of canonisation with only a select few making the cut, our ever-emerging and constantly burgeoning literary scene allows us to regularly welcome new writers and artists.

Take for instance, local publisher Ethos Books, who gave Ms Oei that opportunity by inviting her to contribute in an e-book series in 2019 for the Singapore Bicentennial. When her friend in Ethos asked if she would be interested in such a project, she found herself ready to take the leap.

“I saw it from several perspectives. One of which was that I could use this chance to grow as a writer and hone my skills. And it’s scary putting yourself out there for the world to browse through your words but when the opportunity came up, I thought, why not?” she said.

She had been copyediting, writing, and even ghostwriting before this, debuting at age 14 in the second section of The Straits Times. Still, she appreciated this platform to engage with the existing artefacts in Singapore.

“I’ve always known I’m a bit of a nostalgic, sentimental person so going through the National Archives, looking at the photos, and listening to the oral interviews,” Ms Oei paused with a reminiscent expression. “I just thought to myself, if only we still had these seaside restaurants or if only we had a little more countryside.”

Similarly, Ms Vincent nostalgically recalled her big break when she found out that Red Earth was a finalist for the 2020 Gaudy Boy Poetry Book Prize (New York). It was the first form of formal recognition that she received for her work after all the rigorous editing she had put it through throughout the course of her creative writing journey.

Each of these writers not only took on the mantel but graciously made spaces of their own for budding creatives around them. From Mr Singh’s Andas Productions to Ms Vincent’s eco-journal, The Tiger Moth Review, to Ms Oei’s online magazine Mackerel; these writers have both left their footprint on the Sing Lit scene as well as creating platforms for others to follow in their footsteps (with their own creative voice, of course!)

Epilogue: Moving beyond localisation

Nevertheless, as we champion and celebrate the local literary scene, it’s worth noting that one should not define themselves solely within the scope of Sing Lit, lest we ironically contradict the very move it is making.

The unexpected thread that stitched the stories of these writers, for instance, was how none of them started off—nor do they necessarily do so now—setting out to make a work of Sing Lit. Rather, they each found their respective stories to tell and set forth writing them, eventually finding themselves embraced by our literary scene.

In fact, it is odd that I even considered that anyone might actively begin wanting to write a quintessential Singaporean story. I would never have asked the same for British or American writers. Rather, it seems that we may need to stop categorising Sing Lit as Sing Lit first and foremost to give it a better chance of standing out.

“We can’t force anyone to do anything,” said Ms Oei. “But just as how Netflix brought in several Singaporean films and made them widely available, what if we could find new ways to make literary art accessible to the masses?”

Her comments highlight how the mediums in which we receive Sing Lit could go a long way in normalising its existence and importance. If we could push Sing Lit to the front and centre through more mainstream platforms, it is possibly that we could move past perceiving Sing Lit in isolation but rather as part of our robust genres of entertainment and media.

In an age where we could doom scroll for hours on TikTok or spend more time finding a show to watch than watching it, having a worthwhile story to tell and read seems to be of the utmost priority. Much like how this article needs to be a worthwhile story to you before you clicked to read it.

We can no longer rely on geographical attachments and familiar references to tide through our audience. Writers, of any kind, need to realise that sometimes, their craft simply speaks for itself.

As Mr Singh put it, “what Singaporean show can be received with as much excitement as, say, a Marvel movie?”

What story can we read not because it is Sing Lit, but because it is in itself a work of art?

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.