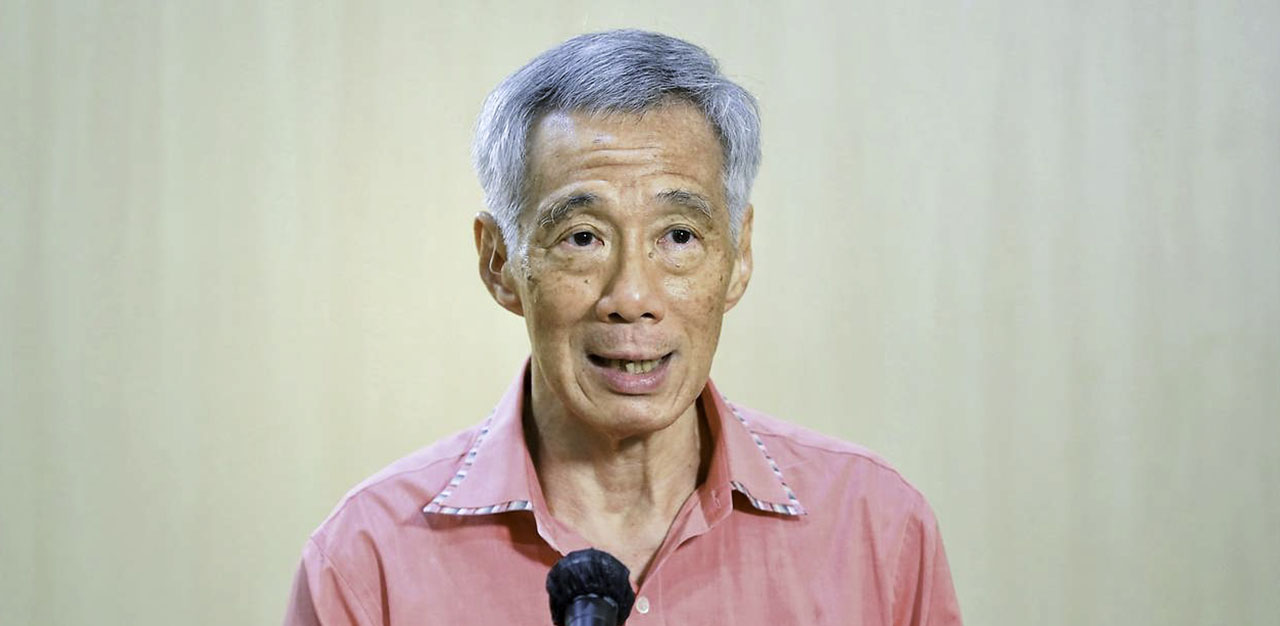

By the end of August, Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong hopes to be able to announce the Government’s decision on whether Muslim nurses will be able to wear the tudung with their uniform if they wish. PM Lee shared the latest progress on this issue after a closed-door dialogue with Malay/Muslim community and religious leaders on 10 April.

In TheHomeGround Asia’s third interview on this topic, we ask Founder of hash.peace Nazhath Faheema for her response to the latest developments on this decade-long debate.

Nazhath Faheema has made it her life’s mission, since graduating from the Singapore Management University 11 years ago, to push for the culture of peace, as well as racial and religious inclusiveness. She does this through interfaith dialogues and conversations around multiculturalism. Having founded the hash.peace movement in 2015, she continues to bring together young people of different beliefs and ethnicities in order to build social harmony and understanding across generations.

Besides being an agent for peacebuilding and keeping, Ms Faheema was first exposed to the issues around extremism and self-radicalisation among youths after being nominated as Muslim Youth Ambassador of Peace, in 2015. She has since been active in raising awareness about counter extremism and the influence of terror ideology among young Singaporeans.

While Ms Faheema acknowledges that she is not directly affected by the tudung ‘ban’ on Muslim women working in public unformed services, she says it is good that civil society speaks up for minority interests that might be unfair or discriminatory, “in a peaceful way”. She adds that the issue of the tudung ‘ban’ concerns her because it also raises the question of how Singapore can “embrace religious diversity in public spaces.”

Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s latest announcement that the Government should prepare to allow Muslim nurses to wear the tudung while in uniform is a “promising, positive progress on this matter,” says Ms Faheema.

Mr Lee had acknowledged that “people’s attitudes have changed, because in social and work settings, the tudung is now more common.” He added that the Government would need to “prepare the ground” to ensure that the public understands this is a “careful adjustment”, rather than a “wholesale change”.

“We want people to realise what the limits are, as we make these changes,” Mr Lee said. “And we must make sure that Singaporeans, both Muslims and non-Muslims, are ready to accept the move.”

He added, “We are a multiracial and multireligious country. It’s a delicate balance, but we are fully committed to preserving our harmony, and to maintaining our common space.”

To this news, Faheema says, “It’s good to see that the Government is setting a timeline to decide… Looks like we are working towards an objective of finding a solution for Muslim nurses who want to wear their religious headscarves to work… How this matter is handled by the Government sets a precedent for policy matters regarding religious diversity in secular spaces. As such, in the coming months I hope the Government carefully considers the opinions of the Muslim community and the other non-Muslim groups. That would be fair, I believe, in a multireligious society.”

Having been involved in encouraging discourse on race and religion, Ms Faheema notes: “I am hopeful and quite confident that regardless of religion, most people will be supportive of the Government’s move to allow our Muslim nurses to wear their religious headscarf, if that is their personal will,” adding that she has observed this support during hash.peace conversations.

She shares that one of the questions raised with youth participants during these sessions was how Government and civil society could talk about religious diversity: “Commentaries made about ‘closed-door’ dialogues need closer consideration. It shows how the young generation in Singapore want to have conversations with the Government on such matters… This is a very important takeaway, especially for the 4G (fourth generation) leaders.”

Ms Faheema suggests that the Government “works towards honest and deep dialogues on these matters” and that information about the discussions are shared “with people in the best way, so they gain confidence – be it closed-door or any other format.”

She adds, “I look forward to a positive decision that not only caters to the needs of today, but also gives a good precedent for [the] future. Let’s resolve the issue for our Muslim nurses first and learn from the experience of handling such conversations”

Here are some of Ms Faheema’s thoughts around various aspects of the tudung issue.

(Note: The interview below was conducted before Mr Lee’s announcement on 10 April and has been edited for clarity and length.)

On how things have evolved since the tudung issue surfaced in the public sphere in 2002 over schoolgirls not being allowed to wear the headscarf in school

Faheema: We must bear in mind that in 2002, when this issue came up that was also post 9/11. It was also the start of Islamophobia. Under that kind of context, it does make sense not to try to do anything that will single out or target Muslim women. But that’s 2002. In the [almost] 20 years, what is not being evaluated is firstly, the role of Muslim women… [their] presence in various sectors… involvement in activist work or in social work, where their voice has changed a lot. [Also] in terms of our Members of Parliament, our president. So much has changed. So if we still seem to have the same fears as 2002, what has been the impact of this change to the role of [Muslim] women [in society]? Has it not had any impact on clarifying prejudices?

We also have invested quite a lot of effort to build social harmony; the Harmony Fund, the IRCCs (Inter-Racial and Religious Confidence Circles), we’ve got so many groups working on inter-faith. And yet, we seem to be grappling with this complexity of managing, I quote, ‘the different aspirations [and expectations]… between communities at the same time’. That makes me wonder what have we not done to strengthen the understanding between different communities that live in Singapore?

Are people still having such prejudicial thoughts about Muslim women? It becomes a broader question of whether people who tend to openly practise their religion through [wearing] visible identity markers face certain uncomfortable experiences in this country. If the answer is yes, then it’s a very disturbing answer.

It shouldn’t happen in my Singapore because we’re supposed to be the country that’s advanced enough in this kind of effort. We’ve got so many young leaders out there who are putting so much effort into [building] religious harmony.

On whether Singapore is ready to talk about sensitive issues and what is needed to harness these discussions for good

Faheema: I don’t know whether we’re still living in an environment [where] speaking about each other’s religious differences is not comfortable… Unless they [people with prejudice] are at ease to discuss religious issues, we’ll never find out why a person might not want to be served by [or feel uncomfortable with] a Muslim nurse… What does it mean for them? We haven’t had that conversation.

The second question is are we so afraid to have that conversation? Why is this conversation not possible when our public discourses or national discourses on various issues have become much more vibrant and dynamic. Maybe because knowing ‘why’ is going to create a lot of unhappiness between people. I’m not so sure that I want to know from a person why he doesn’t want me wearing a tudung and standing next to him. Even [with] good intention and honesty, I’m still going to be unhappy and hurt.

So before we start discussing prejudice, there has to be a lot of effort to make sure that people who learn the truth about the prejudice need to know how to manage it. And it’s two-way: Whatever the person says, and how I react to it, will determine how he sees not just me but an entire community. This involves more genuine dialogue at the grassroots level.

And then thirdly, do we really want to hear the truth and are we ready to handle the truth? Because many times online communities make me feel like they’re not ready to face the truth… There’s so many harsh statements made. I don’t think people manage that well. And whether that kind of conversation creates something better, or more polarisation?

On why closed-door discussions are a way to manage sensitivities but could potentially breed suspicion

Faheema: There are so many questions that need to be deeply considered. There has to be a lot of effort on how to manage the honest and truthful discussions, which is why sometimes I feel that it does make sense to discuss [these issues] behind closed doors. I, as an example, prefer to discuss such matters when I know the people in the room and I can trust that my opinions are objectively considered. I need to have trust established. Not everyone is courageous enough to walk into a room of strangers and give opinions on this kind of issue. That is the reality of it. But the problem is that we don’t know what happens after closed doors; we don’t know what the outcome of these discussions are.

There’s the other aspect of who has to be in the [closed-door] conversation because they should witness the conversation. This should be community leaders with ground access to people. Of course, I do not expect them to report on everything [that is said] but I think they can help to calm the waters and give people a little bit of information about what happens [in closed-door meetings]. Some of them may be doing this. More can do so.

We have to also make sure that the people who are not in the room are pulled into the room if they need to and only [if] they have something to say. If that doesn’t happen the bridge-building is not there, I don’t know how we will actually identify people who have this prejudice. It should be between the nurses who may have experienced it firsthand, and the [prejudiced] party. I don’t know whether volunteers or officials will take up this responsibility, that’s another administrative question. But I think the Government can do something about it.

On whether dealing with prejudice is the crux of the issue

Faheema: A person who’s prejudiced will be prejudiced no matter what, I don’t think it’ll make a difference whether it’s colour, a turban [or headscarf]. As long as the person comes from an exclusivist group, they are going to be against anyone who’s different from them.

I can understand managing different aspirations, expectations and trust. So what are we lacking to create that high level of trust despite so much effort? Maybe a lot of efforts are not reaching the points where they should. Even I, as an activist in this area, would be guilty of it. Have I made enough effort to understand the deep prejudice in society?

On the explanation that the ‘ban’ protects Muslim nurses against discrimination from patients

Faheema: We should be confident enough for people to step up and say that as Singaporeans we won’t allow for that [discrimination]. I think a government, too, needs to be given that assurance, and if despite that assurance the Government decides not to [listen] then I think that’s wrong. But I was thinking in my head all the chaos about Count on Me Singapore then I’m thinking Singapore can I count on you?

Have Singaporeans matured or come to a point where they can band together, and decide what kind of Singapore they want, as opposed to always looking to our leaders to make that decision? That’s my angst… I thought it would have been nice to hear the non-Muslim, non-religious community stand up and say, ‘No, that’s not true. That’s not us, we won’t do that. And if any of us does do that, we will stand against it.’ I have seen some of these voices rise up – online and offline – which made me happy. But this is not enough. I’ve also seen a lot of voices politicising the matter. I know I can count on my friends, if my headscarf is under threat. But we’re talking about a national identity; that voice is not strong.

So many civil society organisations can step up and say, ‘Look, there’s education needed in this area for people to understand why. We can provide education for it. We can explain. We can help the hospitals with it.’ We’re supposed to be setting an example for the region and other countries.

On what it means to maintain neutrality in handling sensitive issues like religion

Faheema: It’s convenient to just couch this as a Muslim issue. But to me, it’s sad. To me that is us trying to help one particular community, neglecting that there will be others [affected]. But [some might ask] why aren’t other communities saying anything about it. So why care? But if we come to this acknowledging that we are a multireligious country, and there are different kinds of people we are going to engage with, in a hospital or not, isn’t that already a step forward? We cannot move forward if we fear differences and want to pretend that this person serving me is not Muslim… or is Muslim? Or any other race or religion?

Are we extending such a policy [removing visible religious markers like the tudung] to everyone else? Are we looking at who else is facing such a problem? Until that question is being discussed openly, it’s not neutral. It is still slanted towards one religious community. But I don’t know how comfortable we are in asking such questions. There might be far more sensitive and difficult-to-resolve issues.

On whether this is an issue of gender rights too

Faheema: I don’t know whether [framing it as a gender issue] will help. [But] since we are all about celebrating SG women, it might help in that narrative. I think there definitely will be more support from a lot of women activists and stuff. And it might be for one reason; this issue about Muslim women and patriarchy, or the fact that they are being hindered by family traditions, or what is insisted as religious obligations for women. This is a long-due conversation that’s always there. I also worry will people start using this change as a way to pressure others into wearing the headscarf, even if against their will? If making it a women’s conversation will protect the freedom of the female as well, I would say it’s a benefit.

On what sort of society we want to build

Faheema: I have met people from different parts of the world who are always in awe of our racial and religious harmony. Some of them live in multicultural metropolitan cities. They live peacefully with people of different ethnic and religious backgrounds too. But, what is so unique about Singapore’s social cohesion? Our whole-of-society approach in which the Government has done well to prevent conflicts that are motivated by ethnic or religious differences. We have been successful in protecting ourselves from extremist attacks and riots, etc. We must admit that this is because of the regulatory framework, policies and the security system.

On top of that, the collaborative approach taken by the Government and the community leaders. This is an achievement, one which many countries grapple with. I am proud of this.

But, can this alone be the pride of our racial and religious harmony? Especially when we are moving towards the fourth generation Singaporean society. Our peace and harmony cannot be based only on stricter laws and tougher policies. I think it has to be based on interpersonal relationships that are able to have difficult conversations. Civil society needs to mature to have dialogues that can proactively deter exclusivist mindsets and the growth of extreme ideologies.

Yes, this sounds sound idealistic, but is it impossible? I do not think so. I see this possibility in small groups, so how can we amplify it [to the wider community]? I want a society that is thinking about how to solve this situation. And I pray that this happens before Singapore’s fifth generation.

Read our earlier interviews on the tudung ‘ban’ with Nur and Ann of Lepak Conversations and Noor Hanisah of Social Greens.

Join the conversations on THG’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.