As Father’s Day draws closer, TheHomeGround Asia speaks to three single fathers to shed light on their unique experiences, and what it is like to be a part of a community in Singapore that often goes unseen and unheard, as they handle the demands of parenthood.

Single fatherhood fell on 44-year-old Terence Low’s shoulders without warning two and a half years ago with a phone call.

One evening in 2018, he returned home to find his wife out and thought that she was perhaps at church camp, since she had taken some of her belongings with her. He recalls asking his son and daughter (then 11 and 8 years old, respectively) where their mother was: “They said ‘Mum went for some event, didn’t tell us.’”

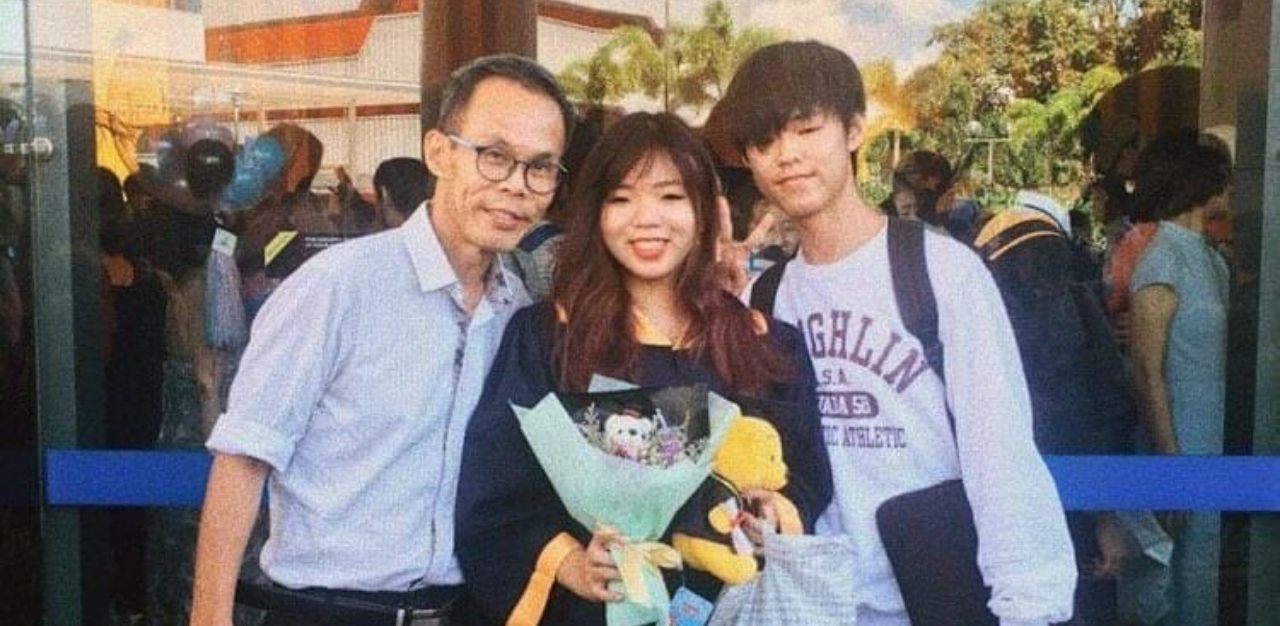

Soon after, Mr Low’s son Jonas, who turns 15 this year, remembers how an ordinary day turned into one he would never forget, when he learned that his mother would not be coming home, for good.

“She called home. My grandmother picked up, passed the phone to me… She told me that she found a place somewhere, a place to rent,” he says.

She subsequently asked Mr Low for a separation, which ended in a divorce in August 2019. “We thought we’ll just try to work it out, but she very abruptly left the house, and then asked for a divorce,” he says.

Something had felt amiss during the divorce proceedings, he adds, as she had ensured that he would have full care and control over their children, although they shared custody.

According to several legal experts online, the court in Singapore usually grants joint custody to both parents in the event of a divorce, save for exceptional circumstances. While care and control of a child is awarded to one parent, often the mother, who becomes the primary caregiver.

His ex-wife’s abrupt departure left Mr Low floundering, and he had contemplated ending his life: “I had [the] idea to leave everything. Go to some tall building and just end it.”

But his attempt to leave his children with their mother, by asking them to wait for her at a McDonald’s as he observed them from a nearby pillar, only made him realise that he had to fulfil his responsibility as their sole caregiver.

“As I observed them, I felt that I just couldn’t lose these two. I always thought that even if she had left… Maybe I could just fight for it, get her back,” he shares.

Mr Low’s hopes for a reconciliation were further dashed when his ex-wife died unexpectedly from hypertensive heart disease in November that same year. “When someone passes away, all hopes of trying to reconcile just dissipate,” he says. It was a tragic-filled time for him, as his grandmother had just passed away two weeks earlier.

In hindsight, he believes that his wife might have been trying to cushion him and their children from the blow of her impending death.

“Emotionally or physically, health-wise, she was not good. Maybe she thought her time was almost up,” he rationalises. “So that’s why she chose to go away alone.”

Mr Low is just one among a silent community of single fathers in Singapore –

a group that often goes unheard and unseen.

“It does seem like we are the forgotten group. I don’t think there’s a statistic to trace how single dads are doing in Singapore,” he points out. “No one is actually keeping track of such things. We’re just trial and error, going as it is.”

The struggles of single fatherhood

Having been awarded care and control of his son Adyan since his divorce in 2011, Mohammed Raziff bin Abdull Hamid, 52, acknowledges that at least, he has a relatively amicable relationship with his ex-wife.

“We know that our son is the utmost importance, so whatever differences we put aside just to take care of his needs,” he says. “The agreement is liberal access for the mum, 24/7. You want him, can just come and take him. My only ask is half an hour before you come, at least give me a call so that I can prepare.”

There were signs that the divorce had affected his son growing up. Mr Raziff recalls one painful moment when he realised that Adyan was uncomfortable socialising with other children.

“All the children when they play at three, four years old, they will run back to their mum,” he says. “He doesn’t want to be seen with the other kids. And the reason because he [doesn’t] have a mum.”

This incident led to Mr Raziff making a commitment to be present for his son, especially when it comes to school events and performances.

“Although I can have [his] grandmother or grandfather there, without saying, he knows that all the [other children’s] parents will be there, so he wants his parents to be there,” he says.

“Most of the time, I’ll be there for him in school so that he won’t feel left out just because he doesn’t have a mother.”

Aside from meeting their children’s emotional needs, having the financial means to bring their children up is another concern for single fathers.

Mr Low worries about his ability to make ends meet. He describes himself as part of the “sandwich class”.

“I come under the sandwich class – not necessarily I am low-income but neither am I having a huge paycheck to cover a lot of things,” he explains. “Initially, I could get by with some financial assistance. But I got a pay rise, and then I couldn’t get all the financial help that I would get from MSF (Ministry of Social and Family Development). So I basically couldn’t qualify for [financial assistance].”

Another hurdle single fathers face is the perception that they are less conscientious than mothers. “I think they feel the guys tend to be a bit more laissez-faire. Maybe a bit don’t care less; not so meticulous in caring for the children,” posits Mr Low.

No man is an island

Then there is the issue of finding emotional support.

For Charles Tan, emotional support comes in the form of a chat group that mostly involves other single fathers. He meets up with his fellow group mates once or twice a month to discuss common struggles regarding parenting and spiritual matters. But, he notes that personal issues usually surface less frequently.

“I think we just have to leave it to them. If they want to talk about it, it’s fine. Grief and loss is something very personal,” he says. “So we just need to be there for each other.”

A widower, Mr Tan lost his wife to lung cancer in 2012. When she was diagnosed the year before, he was working in Australia, and intended to have his family join him later that year.

“Lung cancer is known as a silent killer… People don’t show any symptoms until probably stage three or stage four. By then it’s quite late already. The tumour has already started in the left lung, but spread to the brain,” he shares.

In the wake of his wife’s death, Mr Tan grappled with loneliness and emptiness, as he adjusted to a life alone, and took on the sole responsibility of caring for his children.

“She was my lifelong companion. So her passing away hit me really hard. I suddenly felt very lost, heartbroken, devastated,” he shares. “The world around me had totally crashed and collapsed,” he added, saying he felt “totally alone” with his grief and loss.

“I think it’s a common feeling that we all have – the feeling of isolation. It’s not that we want to isolate ourselves, just that people are not so forthcoming to come and talk to us,” Mr Tan explains.

Adapting to single parenthood was not easy, especially since his wife had been a stay-at-home mother: “I think I just left it to her to take over the role of parenting the kids, and even discipline the kids, whereas I was busy working,” he says.

“[When] my wife passed away, the challenge becomes even more daunting for me, because I realised I don’t have all the skills, the knowledge and experience that I need to be able to be a good parent to my children.”

Relating the struggles of single parenting did not come naturally to Mr Tan, he was uncertain if others would be able to “show the kind of understanding, compassion and empathy that we need.”

He elaborates, “Maybe other guys find it hard to respond to us. We are more likely to share our issues and struggles with friends and other people who are willing to listen and show their care and understanding to us.”

Seeking help can be onerous too, shares Mr Raziff, whose discomfiture in expressing his feelings further prevented him from opening up: “I guess men are more… egoistic. We think we are always in control, we can do things,” he says. “I won’t be able to sit down with an expert to say, ‘Yeah, I need support for this.’”

Mr Tan attributes this to the different ways that men and women are socialised. “It’s got to do with socialisation processes from young. We have not been [conditioned] to express our emotions, and we think that showing our emotions might be considered weak by other people,” he says.

As a Prisons Counsellor, he counts himself fortunate in being more comfortable talking about his emotions than fellow single fathers: “Talking about emotions comes easier for me, because we have to talk to clients about emotions.”

But at home, speaking to his children about their mother’s passing has proven trickier: “There were times when I did try to bring up the subject, and they didn’t want to talk about it… [My daughter] did say that she was feeling sad during Mummy’s funeral. My son, on the other hand, didn’t show any emotion.”

Time, though, has enabled him to develop a closer relationship with his daughter Shema and son Rhema, but Mr Tan acknowledges that the process is a work in progress.

“I’m trying to make myself available,” he says. “It’s a mindset shift I’ve to change on my part, recognising that while I’m still a father, as the kids get older, I have to relate to them more like a friend.”

More financial advice and support can lighten the load

Aside from better avenues for emotional support, Mr Low thinks that providing more financial resources is also key to meeting the needs of single fathers.

“Finance is one of the top things that we always are facing,” he laments. In order to improve his family’s financial situation, the single father enrolled in workshops meant to teach him how to invest his money, which ironically, took a further toll on his financial resources.

“I went for workshop after workshop, which is why I probably exhausted my finances… There’s the desperation to want to make it better than a family that’s traditionally with two [parents]… and to see how to really support my two kids,” he says.

The admin executive, who works in a bank, recently opened a store in Lucky Plaza selling plastic paraphernalia, such as lunch boxes and shelves. Mr Low sees the space as a way to give back to the community, as he intends to hire other single parents to help run the shop. Still, he worries about how long he can sustain this venture, which was launched at the start of phase two (heightened alert), as business has been slow.

It takes a village to raise a child

Having a reliable support system of a loving family has been a lifeline for single fathers like Mr Low, who says that he is grateful for his parents.

“My dad came in and he supported me,” he says. “He’s someone to talk to and bounce [ideas off], see what can be done.”

Similarly, Mr Raziff’s folks have been integral in raising Adyan. “Both my parents [are] living with me. So [his] grandfather and the grandmother [are] critical in [his] growing up,” he says, which was partly why his ex-wife wanted to give him care and control of Adyan, as they have been a constant presence since his son was a baby.

He maintains that his friends have also been central to Adyan’s growing up, especially after he moved back to Singapore with his son last year, and initiated more meetups with friends. Prior to the move, they had lived in Johor Bahru for five to six years.

“All my Facebook friends are his friends… He talks to them like he’s talking to adults,” he says. Adyan has even initiated meetings with Mr Raziff’s friends on his behalf: “He’s that close that he can ask and sometimes make me paiseh (meaning ’embarrassed’ in Hokkien) when he asks without my permission.”

Mr Tan, too, appreciates the kindness of loved ones: “I am very thankful to receive some spiritual and emotional support from my church; pastors, friends, colleagues, relatives, who showed care and concern for me and my kids during my journey,” he shares.

“I feel like I am a father as well as a mother,” Mr Low admits. Although he adds that he is clueless about approaching “girl issues” when it comes to his daughter, Eva, who turns 12 this year.

“Certain girl issues I don’t know how to sit with my daughter to tell her, so I’m very thankful that I have my mum,” he says.

Mr Raziff jokes that his friends refer to him as both a mother and father. But he is quick to point out that he does not see himself fulfilling both maternal and paternal roles. Rather, he sees these duties as part of his responsibilities as a father.

“I don’t feel like I’m a mother and father, but I have a responsibility to fulfil whatever responsibility, A to Z, there’s no separation,” he emphasises. “If you have a wife, then you say I take A, you take B, I take C, you take D. But for me, A to Z is just my responsibility.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.

Where to find help:

Samaritans of Singapore: 1800 221-4444 (24 hours)

Institute of Mental Health: 6389-2222 (24 hours)

Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800 283-7019 (Mon to Fri, 9am to 6pm)

TOUCHline: 1800 377-2252 (Mon to Fri, 9am to 6pm)