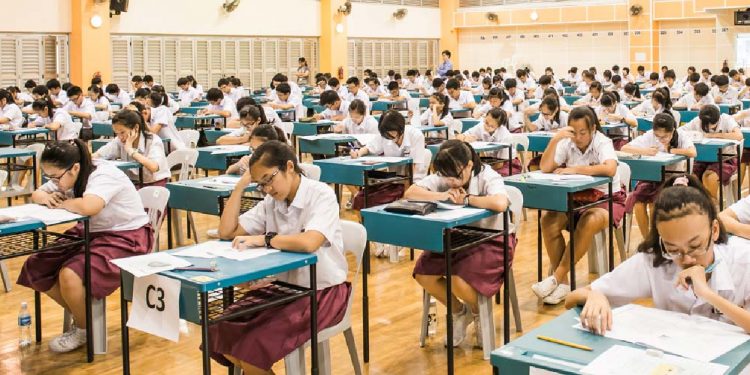

“It sucks a lot [and] it is very tiring.”

Those were the candid thoughts from Kim (not her real name), a 15-year-old student that TheHomeGround Asia speaks to, says when asked about the stress she faces from school. She remarks that part of the pressure is because there are “a lot of tests in the same week”.

After the alleged murder of a 13-year-old RVHS student by a 16-year-old schoolmate on 19 July, the hot button issue of an overtly stressful MOE education system reignited with fervour.

On 2 August, the conversation kickstarted again when a teen was found walking perilously along the track lines at Yio Chu Kang MRT and leaning over the railings.

Over the last few years, MOE has adjusted some parts of its curriculum to ease the stress from exams and introduced life skills subjects to equip students with coping mechanisms.

To understand the stress in schools, TheHomeGround Asia speaks with seven secondary and junior college students about their experiences attending school in Singapore, along with an exploration of how parents and students should cope with stress.

(NOTE: Apart from Emma Wong and Evan Wong, all interviewees agreed to speak to TheHomeGround Asia on the condition of anonymity, and their names have been changed to protect their identities.)

MOE’s education system pivots to tackle stress

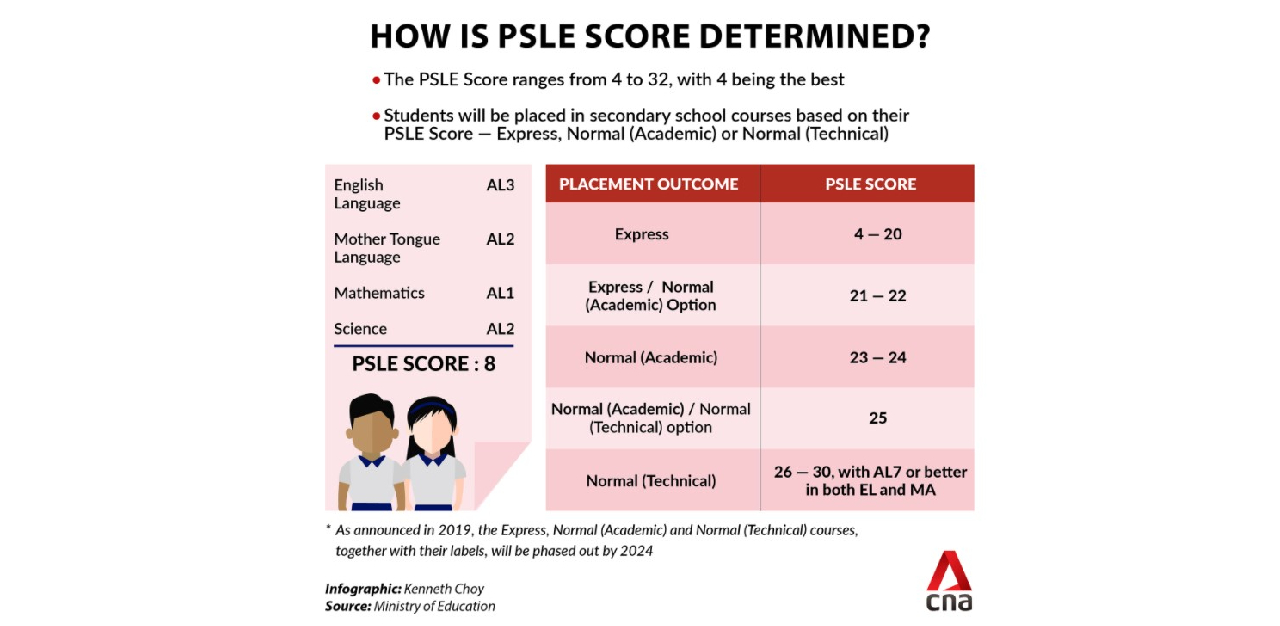

Annual school-leaving exams are a significant source of stress and worry for both parents and students. How well one performs would determine the calibre of a school a student advances into.

In response, MOE announced the new Primary School Leaving Examination scoring system on 6 November 2020, where band ranges replaced total scores.

The cut-off points system is meant to reduce the obsession with scores and narrow the gap between the ranking of various schools.

Courses in secondary schools, such as the Express (Integrated Programme), now hold a range of 6 – 9 Achievement Levels which will put schools within and among government, autonomous and independent types on par with each other for this top tier.

Another way the MOE has attempted to prioritise grades less is by introducing a full subject-based banding in secondary schools, which will replace the current four-course streaming system by 2024.

Ong Ye Kung, then-Minister of Education, said in January 2020 that this would allow students to maximise their unique strengths in various subjects.

In addition, this will free them from limiting themselves to believe the stream they are in is all they can accomplish academically.

In 2018, the Direct School Admission scheme was also made mandatory for all secondary schools, where other talents such as arts and sports will be factored in during admission. Using selection tools such as trials and auditions, the DSA scheme de-emphasises the sole importance of academic results and focuses on a student’s holistic ability.

Jin, a 15-year-old student, welcomed this. In his view, “focusing on talent instead of [grades] is way better as it is [based] on what the [student] is good at”. After all, he feels that non-academic skills are essential in excelling in the working world.

Kim agrees. She finds it “interesting and helpful as the school [will] not be forcing us to always study but also [focus] on the talents or interest of the [student]”.

However, Debbie, an 18-year-old student at National Junior College, feels the exact opposite. She asserts that some students think it “does not develop skills but [co-curricular activities] could contribute to increased stress”.

“As [CCAs] have records, students feel pressured to [attain] different [leadership] positions and take part in competitions so that their records look good,” Debbie elaborates.

Teresa, a 17-year-old Raffles Junior College student, shares the same sentiment. She feels that CCAs are just another aspect in which students would feel pressured to perform well in, on top of academic subjects.

“It is undeniable that [CCAs take] up a lot of time and physical (and mental) energy,” Teresa adds.

Experiences in attending a school in Singapore

Although changes have gradually been made to place lesser importance on academic results, the stress faced by students is often a matrix of factors interplaying.

When asked how many hours Evan Wong, a 16-year-old student, studies on average in a week and the number of subjects he takes, he replies five and eight respectively. When asked to share the reason behind the number of hours he studies, Evan says: “I am not academically pressured [as I] can pick up concepts quite easily. Some simple revision reinforces it, and I can remember most of what I’m taught.”

However, things are different for his sister, Emma Wong, an 18-year-old junior college student. She studies 41 hours a week and takes six subjects. The reason why she studies that many hours is because she faces “high levels of competition in school, [the] fear of not being able to enter my desired course in university, [and the] fear of being seen as a failure if I do not succeed academically”.

As a result of this pressure, she finds junior college life “very draining” and feels that she has no time to engage in any relaxing activities as she doesn’t “do anything else other than study”.

The way the siblings internalise a schooling experience in Singapore is also contrasting. Emma contemplates the benefits and structure of the education system, while Evan considers the friendships that are forged during these years.

Emma feels that the subject called Project Work, graded in the second year of junior college, which aims to “cultivate 21st-century skills such as communication and information literacy, through a group research project”, has taught her real-world skills.

However, Emma feels that there is still a gap that needs to be plugged into the curriculum. While she thinks that Project Work is a step in the right direction, “more can be done to emphasise the importance of these life skills because the national examination system still highly relies on one’s ability to memorise and regurgitate information”.

On the other hand, Evan shares that “when I’m in school, I mostly just enjoy the environment and company of my friends”. He elaborates that “the process [of schooling] and taking examinations” does not bring him that much stress.

That being said, even if the level and type of stress faced may be the same, the experience and stress responses are unique to each individual. Therefore, the same situation may be interpreted differently by two people.

For Jin, stress is determined by how apt he is in the subject. He shares: “The stress from education doesn’t really affect me much as long as I mentally feel like I’m able to [do well in] the subject.” To him, the doubts in his “own capability” to excel in a subject is the cause of his anxiety.

A 15-year-old student, Joon, shared the same sentiments. While he finds the pressure “manageable”, his stress is innate and mainly attributed to the expectations that he places on himself. Joon opines that while someone may be very skilled at managing stress, but it does not mean they do not find it overwhelming at the same time.

He comments that he hopes the education system can be “less stressful” even though he copes with it reasonably well.

Teresa also says that while the “stress is managed well through [engaging in things] that relieves stress and proper time management,” she feels pressured “to always be on top of things (lectures and tutorials) because all the subjects are very demanding and time-consuming” and being able to cope with the workload is of utmost importance in excelling in a subject.

Debbie feels likewise and shares that the JC life has been making her feel “rather bogged [down] and a little [overwhelmed]”. She adds that it is stressful and disappointing if one cannot achieve good grades despite the hard work they put into studying.

“Not seeing hard work being translated into good grades is very disappointing for students, and it adds to the stress as students believe that they [have] to work harder,” shares Debbie. Teresa chimes in that this will lead to a “vicious cycle” because a person’s mental health and well-being may be “compromised”.

It should be good news then when Mr Chan said in the Ministerial Statement that Common Last Topics from the 2021 GCE examinations would be removed due to the disruptions caused by the pandemic.

Upon hearing this, Kim felt relieved as it meant they “do not need to study for a lot of topics”.

Emma agrees. She says that the removal will “help reduce my revision workload and give me greater ease of mind [as I have] more time to focus on my weaker areas”.

However, two students highlighted that the topics removed may be the ones the students enjoy more or are better at, which defeats the purpose of reducing their workload.

Teresa also points out that it may be “disappointing” as students lose their chance to get marks since the “topics removed might be [those many] students are good at”.

On the other hand, Joon opines that “the removal of [lessons that are] fun and enjoyable will lead to students feeling very bored”. He explains that this will translate to a general lack of enjoyment in school, which will cause students to fall behind and then feel the pressure of having to catch up.

Debbie also feels this is unhelpful but for a different reason. She remarks that students would have “already finished [covering] those topics and tutorials”, so it would have been a waste of time and invested energy.

Coping with stress for students and parents

Experiencing school-related pressure is both normal and inevitable and learning how to cope with the stress is crucial.

Emma feels it begins with the mindset. To her, the different life paths people undertake are unique, and that success in life is defined by the individual and not an education system.

She comments that she would like students “to learn that our academic results do not define us as individuals because there are so many other areas which we can succeed in”.

Emma elaborates that students should also internalise that “it is okay to fail” and give themselves “a safe space where they can learn from their mistakes and gain confidence in their own capabilities”.

Teresa also feels a healthy mentality helps curb pressure. “The point is to see that getting good grades is not a [one-size-fit-all] solution to [academic] problems and that trying your best is most important,” she shares.

“After all, people are all born with different skills and abilities and schools [are] just a way to find that and open doors to careers in the future,” Teresa adds.

Another way she copes with stress is by capitalising on the mandatory requirements of the school to destress.

Some find CCAs stressful, Teresa starts, but “personally, CCAs are a good way to get your body moving for health and fitness (for sports CCAs)”.

“Overall [the] benefits outweigh the costs for me”, and that is why she sees CCAs as outlets to “do things [we] enjoy outside of the studying scene”.

Managing stress healthily does not lie solely on the students themselves, as parental pressure in performing well compounds the problem. Therefore, the conversation has to include parents and how they can be part of the solution.

One of the most effective ways that is often overlooked is modelling. Teens still look to their parents for examples, and if a parent does not have a healthy stress management lifestyle, it will be more challenging for the child to learn practical coping skills.

The way to overcome this is to connect with the child over stress. For example, if a parent feels overwhelmed, they are advised to verbalise it and have an open and honest conversation about why they are feeling stressed.

Being upfront with your child will not only show them that stress is okay and is a normal part of life, but it will also exemplify how to develop and adopt a healthy relationship with stress.

Another practical way of managing stress is to limit activities outside of school. Over-scheduling activities, such as tuition, take away a student’s relaxing time and creates more aspects in which they feel the need to excel.

But a hands-off approach is not the route parents should take either. Instead, a parent can let their child choose the kind of activities they would like to do. They can also ensure that they set aside personal time to socialise and not pack it with family activities.

There is good stress and bad stress. Stress can sometimes be detrimental to physical and mental health, but it can also train individuals to be resilient in life. The importance is being able to identify the difference and addressing the issue at its root cause. It has been a challenging few months for everyone and students as they adapt to the uncertainties caused by the pandemic. As the school leaving examinations approach, do reach out to friends, family and teachers should you need help. There will always be someone you can talk to for support if you need any.

If you need to speak to someone about your mental well-being, you can use the following list of resources:

- Samaritans of Singapore (SOS) (24 hours): 1800 221 4444

- Institute of Mental Health (IMH) (24 hours): 6389 2222

- TOUCHline (Mondays to Fridays, 9 a.m. to 6 p.m.): 1800 377 2252

- Eagles Mediation and Counselling Centre (EMCC) (24 hours): 6788 8220

- Singapore Association for Mental Health (SAMH) (24 hours): 1800 283 7019

- eC2 (Mondays to Fridays, 2 p.m. to 5:30 p.m.)

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.