Hi, I’m Ming En. I’m Singaporean Chinese. Hakka, to be exact. But we don’t introduce ourselves that way anymore. We’re just Chinese, all of us. My ethnic subgroup doesn’t matter, for I don’t know my language, I don’t know my history, and I don’t know my heritage.

I wrote a poem once, about being a Hakka in Singapore.

I/We

I am a proud Hakka.

We make up 8% of the Chinese population —

something I only found out today,

writing this poem.We are the fourth largest Chinese dialect group,

but our numbers are still small.We are a minority – special, unique.

—

“What dialect group are you?”

“Pure Hakka!

my mother, father, grandparents –

all Hakka!”“Can you speak the language?”

.

.

.

“I can count!”

and count I do, rattling off numbers

I have long since memorized.I count to 10

in tones I grew up within a language

I cannot actually speakits heritage

I do not know.—

I am a proud Hakka

with shame in my heart.

We are a minority

growing smaller

still.

It was a lament of my inability to speak a language that I should have grown up with, and a bemoaning of the dearth of knowledge I have regarding my own heritage.

Growing up, my parents and grandparents never spoke to me in Hakka. They never saw a need, for schools only call for me to learn English and Mandarin, and the language landscape of Singapore was almost exclusively English and the mother tongue languages by the time I was born.

It’s only when I grew older that I realised how much I was losing out on not knowing how to speak my grandmother tongue, particularly since all conversations within my parents’ and grandparents’ generations were primarily in Hakka.

I found myself unable to participate in conversations, missing out on stories of a time before I was born, and missing out on inside jokes that simply didn’t carry the same meaning when translated into Mandarin.

My story isn’t unique.

Based on Singapore’s census data, the percentage of speakers who mostly spoke Chinese Vernaculars (languages such as Hokkien, Cantonese, Hakka, Hainanese, Teochew and so on) at home have decreased from 74.4 per cent in the 1950s, to a mere 14.3 per cent by 2010.

While the communication barrier and loss of bonding opportunities with the older generation are easily observable consequences of an inability to speak these languages, is that all? What more do we lose when we stop speaking a language?

What languages are we losing, or have already lost?

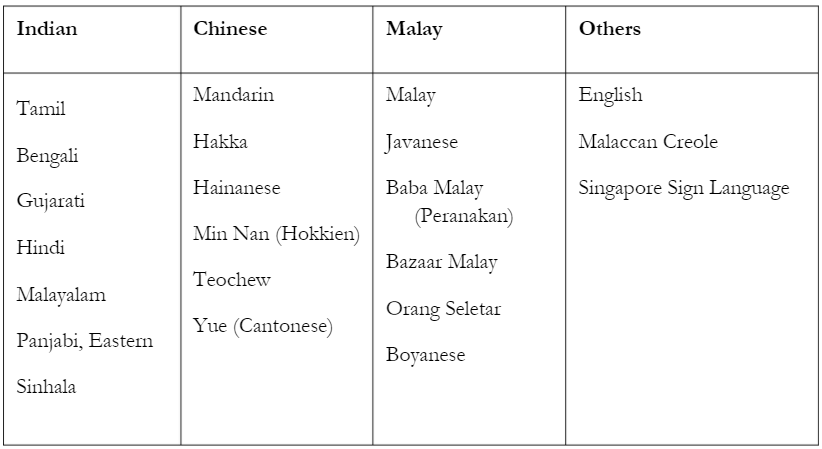

Contrary to today’s linguistic landscape, Singapore pre-independence and pre-colonisation was a diverse one, with immigrants from numerous countries bringing with them their own languages. The table below, adapted from Cavallaro and Serwe (2010), and published by Cavallaro and Ng (2014), aptly summarises the most widely spoken languages in Singapore during those times.

Yet, in the past 50 years or so since independence, Singapore’s linguistic landscape has changed from one that is largely heterogeneous, into one where English is used as the lingua franca (a language used for communication between people who do not share a native language).

This language shift towards English and away from other languages can generally be attributed to government policies and people’s desire for upward social mobility (Li, Saravanan, & Ng, 2010).

The bilingualism policy saw Singapore adopting English as Singapore’s working language, and the three mother tongues (Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil) as the mother tongue languages of the Chinese, Malay and Indian communities respectively.

With these policies in place, opportunities to use other languages once prevalent in Singapore steeply declined. Usage of Chinese vernaculars and other languages not included in the mandate fell.

Why does this matter?

According to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (also known as the theory of linguistic relativity), language influences our thoughts, actions, and worldviews. Many linguists have found support for this theory, finding differences in the way individuals perceive colours, directions, and more.

Under this hypothesis, language isn’t just a mode of communication or transmission of culture, it directly shapes our culture and ways of thinking. For instance, words found in some cultures can convey certain nuances that other languages do not. An oft-cited example of this would be that of the Eskimo languages, where they have a copious amount of words used to describe what we would sum up in one word in English: snow.

In the Eskimo languages, a multitude of words are used to describe different types of snow such as aput for ‘SNOW ON THE GROUND’, qana for ‘FALLING SNOW’, or piqsirpoq for ‘DRIFTING SNOW’ (Martin, 1986).

The environment that Eskimos live in, where snow is a staple and expected part of their lives, necessitates this distinction in their language. And this, in turn, shapes how they communicate and view the phenomenon of ‘snow’ in their culture.

Clearly, language can have a sway on the way we perceive the world. But how important is it to our culture? What happens when a language is no longer spoken? Well, the best way to understand that is to examine a language that is endangered at this very moment.

Case Study: Kristang

To understand the true depth of what we lose when we stop speaking a language, let’s take a look at a community vastly underrepresented in Singapore – the Eurasians. More specifically, the Kristang people, who spoke a language that is their namesake.

The Kristang people are Portuguese-Eurasians, often with a strong Dutch heritage. Their language, also named Kristang, is a creole language developed in Malacca during the Portguese (1511-1641) and Dutch (1641-1774) rule.

Today, Kristang is classified as a “severely endangered” language by UNESCO, with slightly more than 2,000 speakers in Malacca (where the language originated). In Singapore, the situation is even more dire, with fewer than 100 individuals speaking the language. According to Kodrah Kristang (translating to: Awaken, Kristang), a platform hoping to revitalise the language here in Singapore, no children are known to be learning the language. In fact, most Singaporeans are scarcely aware of the language’s existence.

So how exactly did this language end up in such disuse? And what are the implications it has on the Kristang community, and on society as a whole? We spoke with Frances Loke, one of the teachers at Kodrah Kristang, to find out.

While Frances herself isn’t of the Kristang ethnicity, she has worked with many people who are over her years at Kodrah Kristang. Her own experiences of learning Kristang and her encounters with the language has also exposed her to the intricacies of their culture and heritage.

Frances explained that the chain of transmission for Kristang mostly ended with the grandparents’ or parents’ generation, as many from the community did not see a reason to pass down the language when the bilingual policy already meant that students had to deal with two in school. Some also felt that the language lacked prestige against more widely-spoken ones like English.

“Kristang has brought a different level of understanding on what it meant to be Singaporean,” she said, “it allowed me to look at how language policies have been biased [and]… affected the different populations of Eurasians.”

“We all just settle with a label that paints us with a really broad stroke,” Frances adds, referring to the umbrella terms used to group individuals into the four main races (Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Eurasians), and the Mother Tongue languages each of these ethnic groups had to learn. In doing so, we lose the complexity and diversity within our own nation.

Frances went on to cite examples of how within each of the three major races, there exists distinct cultures, each with their own traditions and heritage. For example, within Kristang, there are words that encapsulates the environment and culture of the Kristang people. She says of the language, “Kristang has certain words that just capture what… life was like for a Kristang person. So you would have words, for example, that encapsulates the notion of fishing.”

So what do we lose when we stop speaking a language?

“Ourselves,” Frances answered after a short pause, “there’s no other way for us to perceive the world or communicate about the world other than language. So when we lose that language, we’re also losing a way of thinking about the world, a way of talking about the world, and a way of exploring the world.”

UNESCO sums it up nicely: “Every language reflects a unique world-view with its own value systems, philosophy and particular cultural features. The extinction of a language results in the irrecoverable loss of unique cultural knowledge embodied in it for centuries, including historical, spiritual and ecological knowledge that may be essential for the survival of not only its speakers, but also countless others.”

This knowledge is why Frances and the rest of Kodrah Kristang are working so hard to revitalise and preserve the language here in Singapore. Frances shared her own experience of being a Cantonese speaker, and how much it helped her create a special connection with her grandmother as it was the only common language they had.

She related her own experience to that of Kristang, “I was just thinking, if I lost that connection (with her grandmother, if she had been unable to speak Cantonese), there would be such a loss in transmission of culture, transmission of knowledge about the world, history of Singapore, history of the world, customs, [and so on]. I just couldn’t imagine the same happening for Kristang… it just feels like [a shame] if nobody even bothered to save it”.

What can we take away from this?

Here are some sobering numbers for you: today, a third of the world’s languages have fewer than 1,000 speakers left. Every fortnight, a language dies along with its last speaker. By the next century, 50 to 90 per cent of these languages are predicted to disappear (Strochlic, 2018).

The declining languages in Singapore might not be on the brink of extinction on a global scale, but losing them here will mean losing a precious part of Singapore’s history.

Our identity and culture are made up of many things but language undoubtedly plays a significant role. Bearing in mind the example of Kristang and that of other languages around the world that are slowly disappearing, maybe it’s time we view languages with a less callous lens and instead, be more mindful about the languages we use and learn.

For those fortunate enough to have grown up with some of these declining languages, perhaps consider passing them down to your children when the time comes. In whatever shape or form, have them learn a little piece about their history and heritage. Meanwhile, find opportunities to use these languages whenever you can. Keep them alive in our country.

For myself, I’ll be doing what I can to pick up however much I can, from videos, online audio lessons, podcasts, or even formal lessons in due time, should they be available. For others like me, perhaps these are avenues you can consider as well.

Frances acknowledged the importance of Singapore’s language policies in our nation-building years to forge a national identity but now that it’s been done, perhaps it’s time we learned to embrace the diversity within our little island city, languages and all.

References

Cavallaro, F. and Serwe, S. (2010) Language use and shift among the Malays in Singapore. Applied Linguistics Review, 1(1), 129-170.

Li, W., Saravanan, V. and Ng, L. H. J. (1997). Language shift in the Teochew community in Singapore: A family domain analysis. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 18(5), 364-384.

Martin, L. (1986). Eskimo words for snow: A case study in the genesis and decay of an anthropological example. American Anthropologist, 88(2), 418-23.

Join the conversations on THG’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.