On 29 July 2020, Rahiman Rahim kicked his then-girlfriend’s face and stomped on her head multiple times while she was on the ground. He also punched, slapped and dragged her by the hair. It was found that at least seven people walked past the prolonged assault at Rumours Beach Club at Sentosa, but did not intervene. That excludes the staff of the beach club.

On 23 May 2021, a 40-year-old man was seen brutally beating up another man who was curled up on the ground on a train. In the video, at least two passengers can be seen just watching by the sidelines instead of helping the victim.

If it seems the world has become increasingly woke, this conflicting dissonance in being perfervid one minute, and passive the next fails to make sense.

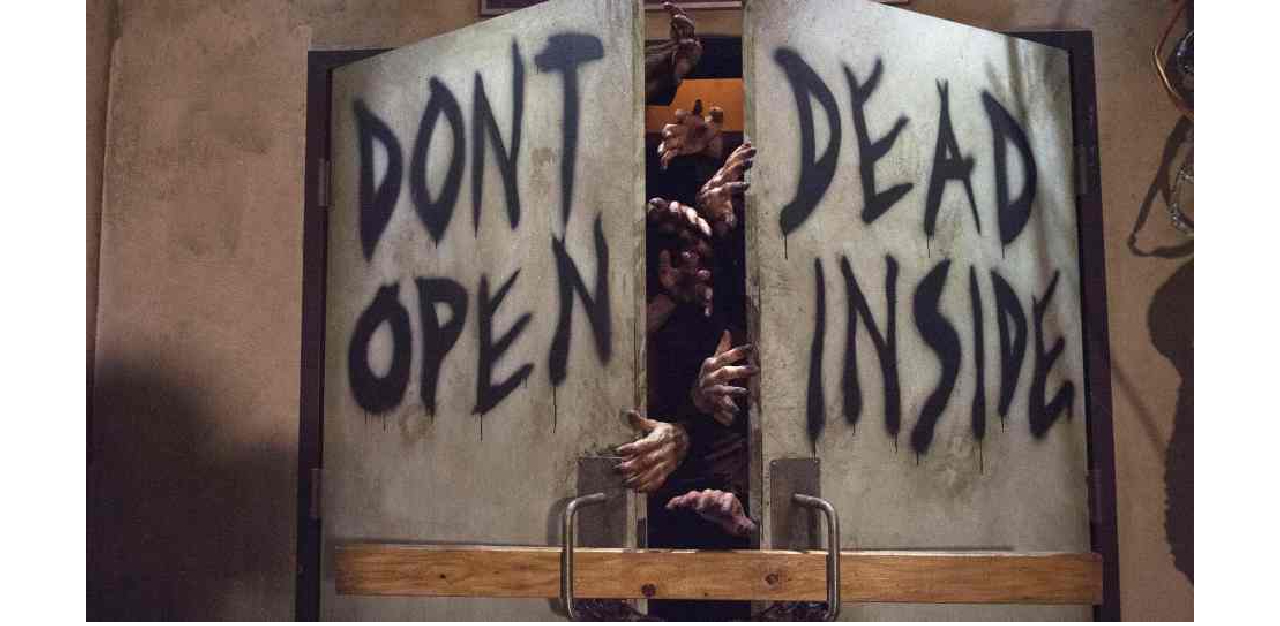

‘Woke digital culture’ online vs ‘walking dead culture’ offline

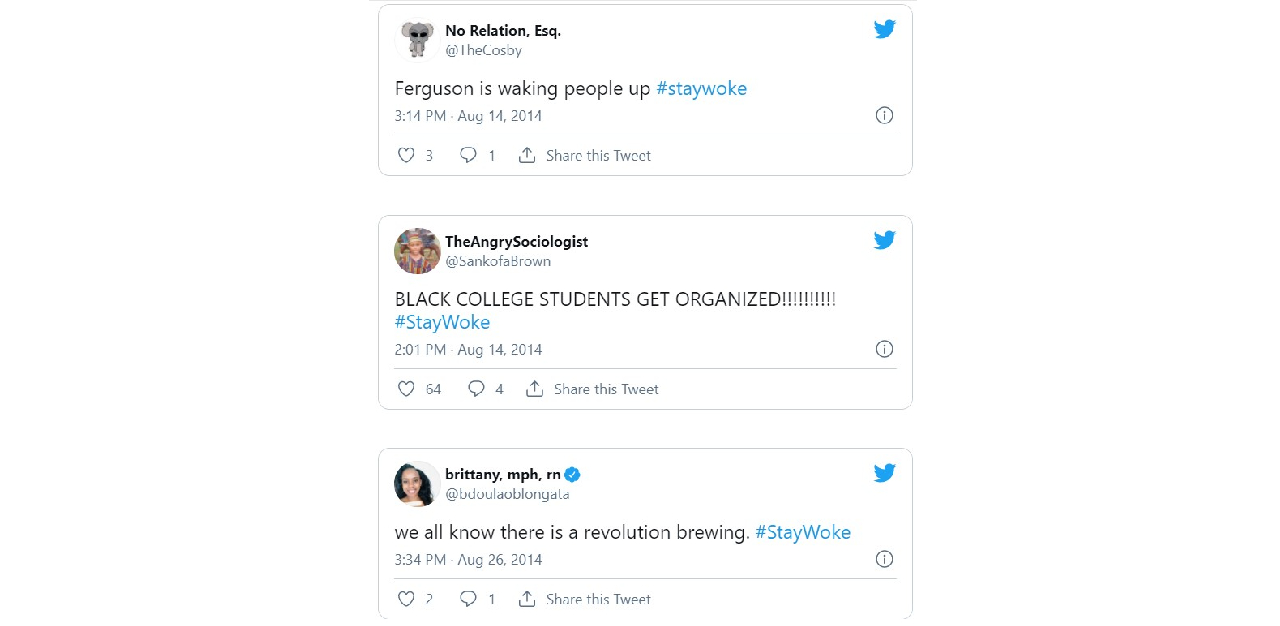

The concept of ‘wokeness’, defined by Cambridge Dictionary as “a state of being aware, especially to social problems, such as racism and inequality”, in other words being alert to societal injustice, was “co-opted” from the impassioned activism of Black communities. According to this report, “stay woke” became the cautionary “watchword of Black Lives Matter activists on the streets”, after the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson in the US, in 2014.

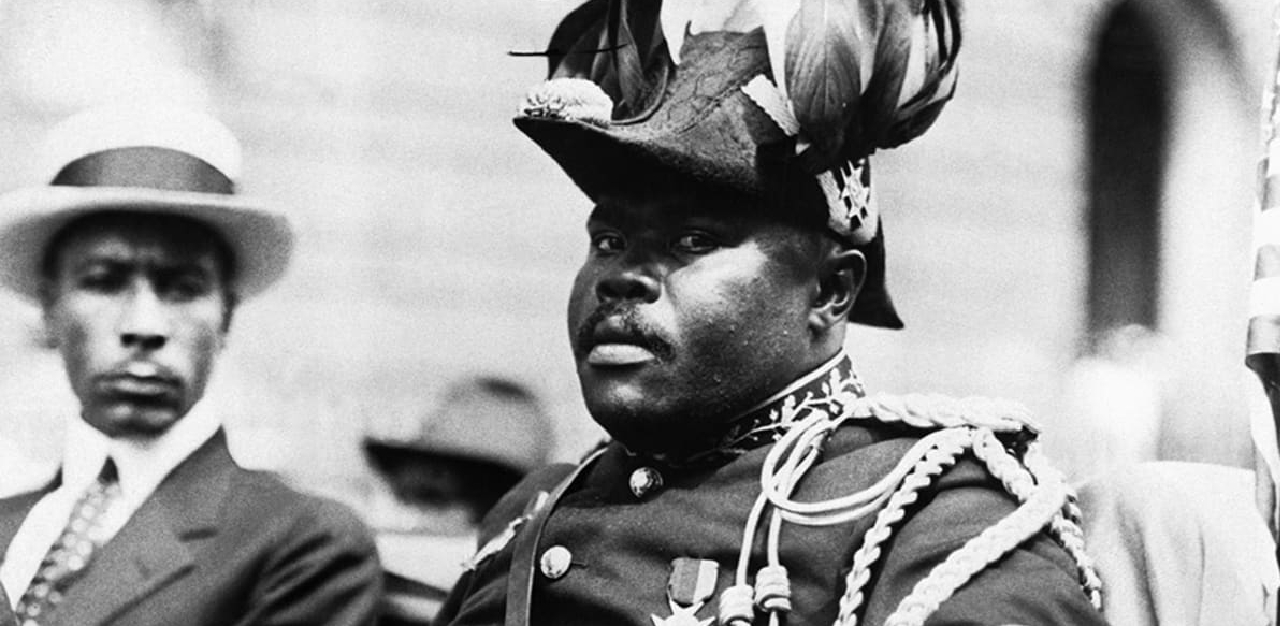

But the first sign of ‘wokeness’ did not just begin in the 2010s, but goes all the way back to the early 1900s. It started as a call by Jamaican philosopher and social activist Marcus Garvey for Blacks to ‘become more socially and politically conscious’. “Wake up Ethiopia! Wake up Africa!”, he wrote in a collection of literature.

It was only popularised and transformed into the ubiquitous term ‘woke’ when Blues musician Huddie Ledbetter, whose stage name was Lead Belly, sang ‘stay woke’ in the lyrics of Scottsboro Boys, in 1938. The song was in a revolt against the nine black teenagers who were accused of raping two white girls in 1931 in Scottsboro, Arkansas. All of them were sentenced to death, except one who was imprisoned for life.

Fast forward to 2012 – and the term has become fully awakened and entered mainstream language. Staying true to its roots and carrying on the tradition, it is about ‘social justice and equality activism’ for Black lives.

On 26 February, 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was shot and killed by a neighbourhood watch White man, 29-year-old George Zimmerman, in Sanford, Florida. Mr Zimmerman called in to the police to report a ‘suspicious person’. He was told not to approach the vehicle that Mr Martin was in, but when the latter got out and started leaving, Mr Zimmerman followed and fatally shot the teenager. However on 13 July 2013, Mr Zimmerman was found not guilty by a six-women jury.

There was a national uproar, and #staywoke gained traction after this incident. But it was only one year after Mr Zimmerman was found not guilty that the phrase ‘Black Lives Matter’ became a slogan of power for the Black community, when Michael Brown was killed in 2014 by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri.

That year alone, Twitter found that the word ‘woke’ was tweeted 30 million times. Finally in 2017, the word was added into the dictionary as an adjective.

A more recent case was the petition for Justice for George Floyd that garnered 20 million signatures. It was the largest petition ever signed. It reflected the depth of how many people wanted the conviction of the policeman who killed George Floyd, which online users had deemed was racially motivated.

Now, would the opposite of ‘woke’ be ‘dead’, figuratively speaking? The phrase ‘walking dead’ is not unfamiliar because of the AMC Networks hit show of the same name. In the show, the walking dead are zombies. But in society, one of the meanings of the term is when someone sees a person in need of help in public, but does not offer assistance.

Specifically, Cambridge dictionary defines it as “a person who is standing near and watching something that is happening but is not taking part in it.”’ This is also known as the ‘bystander effect’, which was first “discovered by psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley following the 1964 Kitty Genovese murder in New York City.”

The victim was stabbed to death outside her apartment, but none of the 38 people who knew of the incident intervened. According to psychologists, the neighbours’ response was “generally half-hearted”. Some did call the police, but one husband was stopped by his wife from doing so, because she believed someone else would have done it already.

Messrs Latané and Darley had conducted experiments to understand the motivations behind this ‘walking dead’ effect. There were two factors: One is the “diffusion of responsibility”, where if “many others (are) present, the responsibility is shared throughout the group, and no one feels that it’s down to them to do anything”; The other is “our desire to conform and follow the actions of others.” If no one does anything, maybe the situation does not warrant help. As put by the psychologists, “emergency situations are often unclear or chaotic, and we tend to look to others to decide on the correct action – or inaction.”

Why the discrepancy between human behaviours in these two domains?

When asked about this contradictory culture in society, where a ‘woke digital’ culture co-exists with a ‘walking dead’ culture, Associate Professor of Sociology Tan Ern Ser from the National University of Singapore, echoes the factors: “People may not take action [because] they do not feel personally responsible since there are other bystanders around [and therefore] unlikely to be held accountable for inaction,” he explains.

A second reason, according to psychiatrist Ang Yong Guan, who runs a clinic in Singapore, is the hassle and inconvenience of getting involved, which “requires too much time and energy that many may not have the time to do it.”

He says, “As a society, people are wary of getting involved with social justice issues for fear of the amount of work and time required and the responsibilities these activities entail.”

For example, if a person intervenes in a fight, he or she would have to give a statement to the police, possibly appear in court to testify, or perhaps visit the hospital to treat injuries. In that sense, people would rather save themselves the trouble.

The third reason is quite practical, as one may feel they are not physically able to stop the assailant. As Associate Professor Tan says, “They feel that they are not competent enough to help [and] do not have the means to offer help.” He adds that while one “could be motivated by compassion to be an ‘activist’, [one may] rationalise that [they] can’t do much about the problem anyway.” Thus, they may choose other less inconvenient ways to ‘help’, such as videoing the attack, or calling the police.

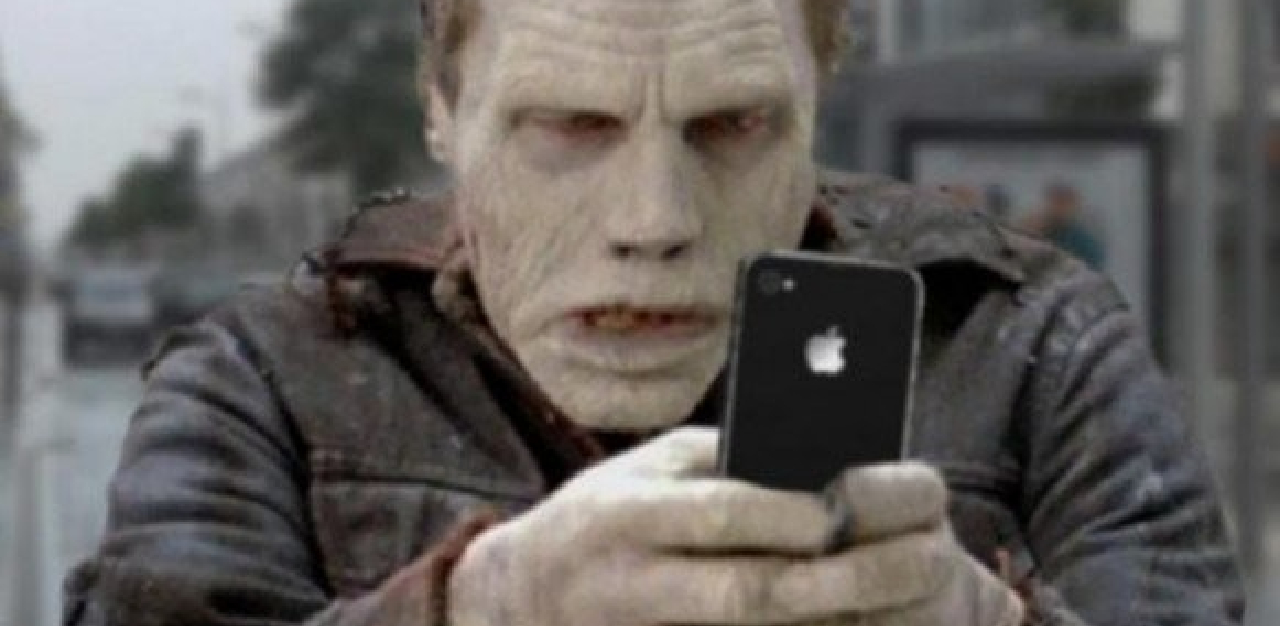

When it comes to involvement online, however, the behaviour is low-risk and low-cost.

As Dr Ang asserts, “Giving comments online and championing the woke culture does not require the much-needed effort and time to do real activities related to their cause – views online are free and can be done [at] any time of the day.”

He adds that being “part of the ‘woke digital culture’…is fashionable [when you] identify [yourself] with other like-minded members.”

Assoc Prof Tan also opines, “It is far easier to shoot down views or positions, which we consider harmful or unjust, while sitting behind a keyboard.”

Words spoken behind a screen and an alias, after all, hold little accountability, and social media users rarely face consequences as they hide behind billions of comments.

Convenience or compassion?

With the boom of social media, news spreads like wildfire, and voices proclaim like trumpets. Woke culture is hailed as activism and a passionate advocate for change, However, the discrepancy between human behaviour online and offline has raised the question of whether society has just been given a convenient platform to express its views, rather than a rise in compassion.

Dr Ang thinks this may be the case, because “social media is a platform where many people wear a social mask, not indicative of their true selves.” In reality, he believes that society still remains “lukewarm and apathetic”.

He explains why that is the reason: “Subscribing to the woke culture and awakening to certain cultural or socio-political issues online is not matched by the same fervour on the ground.”

Assoc Prof Tan agrees, as he argues that “it is very easy to be desensitised to the problems we are exposed to in our everyday life, say, at street corners or subway stations.”

The other reason why society is a ‘woke digital’ culture online but a ‘walking dead’ culture offline is because it is easier to talk than to actually act. Assoc Prof Tan illustrates an example: “[In a] town hall meeting, we may offer all kinds of good suggestions on how to deal with municipal problems. But when asked to volunteer to contribute [or to solve] a problem, we may be more [reluctant] about getting involved to lead or help in implementing our suggestions.”

Dr Ang has observed a similar situation: “Many have become keyboard warriors ever ready to express their views online but not ready to roll up their sleeves to offer real help on the ground.” He further elaborates that actions requiring less hassle might be undertaken, such as donating to a cause. But beyond that, they would rather “stay clear of any groundwork to champion a cause, or do something for the victims or the underprivileged citizens.”

Many worthy causes have sprung out of woke culture, such as #BlackLivesMatter and the #MeToo movement. There is little doubt that woke digital culture has had a positive impact on and increased awareness about many injustices and social issues. That being said, action is always louder than words, and if as a society, people do not practise what they preach, being woke loses all its potency. And you might as well be the walking dead.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.