What if the issue of race was a man-made construct formed by a systematic form of racism embedded in legal, political and academic structures? That humans were born colour-blind, until the different skin tones of our neighbours took on sociological meaning formed by those in power. In the first of a three-part exploration of racism in Singapore, TheHomeGround Asia seeks to understand the origins of racism, how the building of a young nation, through its policies and governance, inevitably weaved racism into its social fabric, and how efforts to catalyse racial integration and harmony would affect the future of Singapore’s race relations?

Public displays of racism and racial intolerance have been making headlines in Singapore over the last couple of months. The simmering tension along racial lines has made the population more conscious of the fragility of its multiracial and cosmopolitan society. By tracing the roots of these divisions, TheHomeGround Asia aims to explore possible approaches that Singapore can take to encourage a more harmonious understanding and acceptance of one another, regardless of race.

Understanding the idea of race and racism

Racism has been described as “the differential treatment enacted by an individual, group, or organisation on individuals, based on assumptions of a group’s phenotypic, linguistic, or cultural differences.”

A recent exchange between Chinese-language broadsheet Lianhe Zaobao and a group of local academics highlights different views on race and racism in Singapore, and the challenges that exist in identifying its root cause.

Rather than viewing the recent uptick of social discord as an anomaly in an otherwise racially harmonious society, local academics in the open letter challenged the view that social media and the pandemic were to blame, and sought to draw attention to the fact that fault lines already existed between races and minorities before the pandemic. They argue that there was a need for Singaporeans to examine their role in structural racism and radicalism. And explain that racism is not simply the existence of hatred and virulence between individuals.

Structural racism, as defined by educator Sylvia Duckworth, refers to government systems, policies and laws that maintain systemic racism. In examining the roots of racism in Singapore, Associate Professor Chong Ja Ian in the Department of Political Science of National University of Singapore outlines the limitations of adopting Critical Race Theory as the sole cause of racism, here. In an article published on Academia.sg, he acknowledges that Critical Race Theory could be used to explore how social structures create societal privilege and injustice in society.

As it stands, a common thread has emerged from all the recent debates and discussions about race and racism in Singapore – that there needs to be more dialogue and understanding between all races.

Emergence of a racial categorisation management model early in Singapore’s history

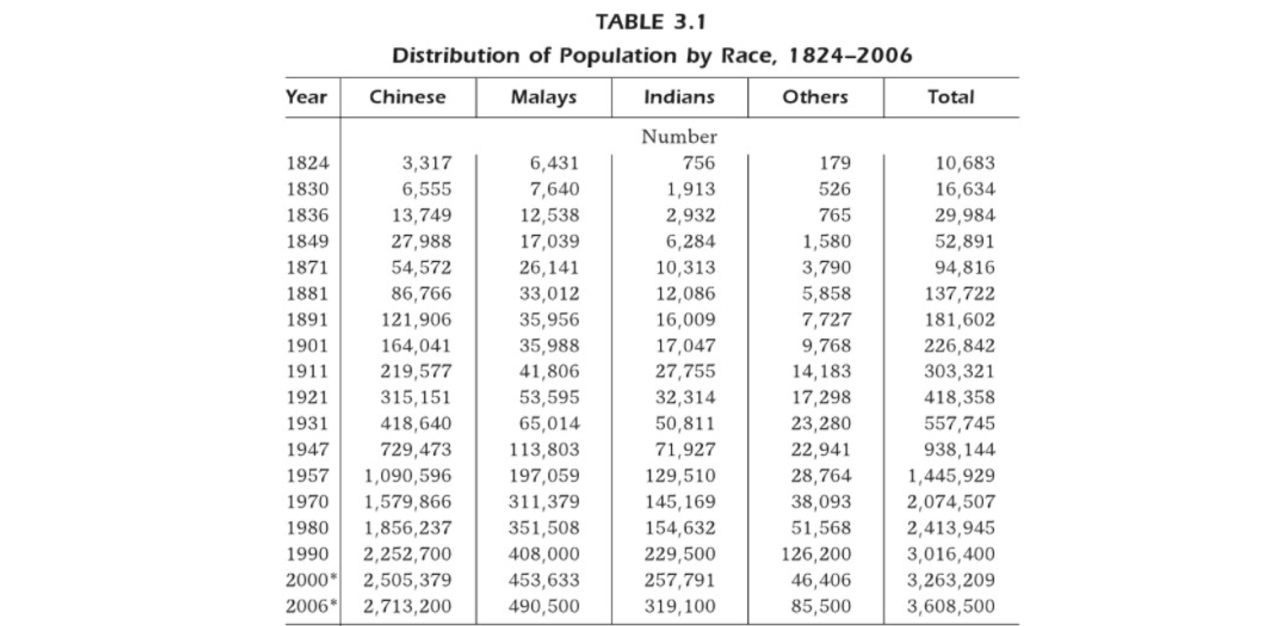

Looking back at Singapore’s colonial past, the current Chinese-Malay-Indian-Others [CMIO] model might have originated as part of the British rulers’ efforts to define race and racial categories, as they sought to organise and develop the island into an efficient socio-economic country. Singapore’s first census in 1824 is unique, in that its racial profile consisted of these four CMIO groups.

Censuses in Singapore have continued to adapt according to the make-up of its population. This has further entrenched certain identities into its people, and has perhaps made them conscious of their racial and ethnic differences. In 1871, the census outlined 33 categories comprising various racial, ethnic, national, cultural, religious, political and socio-economic classifications:

Europeans and Americans, Armenians, Jews, Eurasians, Abyssians, Achinese, Africans, Andamanese, Arabs, Bengalis and other natives of India not particularised, Boyanese, Bugis, Burmese, Chinese, Cochin Chinese, Dyaks, Hindoos, Japanese, Javanese, Jaweepekans, Klings, Malays, Manilamen, Mantras, Parsees, Persians, Siamese, Singhalese, Military – British, Military – Indian, Prisoners – Local and Prisoners – Transmarine.

In 1881, the categories were narrowed to six, with 47 sub-categories reclassified under them:

European and American, Eurasian, Chinese, Malays and other natives of the Archipelago, Tamils and other Natives of India and Other nationalities.

In 1921, the classification took on broader terms and categories were renamed Europeans, Eurasians, Malays, Chinese, Indians and Others, with 56 sub-groups under them. What this did was to conflate complex racial, religious and national identifications into loosely outlined races and ethnicities.

The segregation to integrate multicultural Singapore paradoxically fostered a “medley of peoples – European, Chinese, Indian and native – for they mix, but do not combine.” As people lived and worked separately, both their race and socioeconomic statuses became embedded in their identities, and reinforced intellectual and psychological divisions.

Thus, this classification of ‘race’ was essentially employed as a political tool when the “eurocentric classificatory grid simplified complex identities, fitting neatly with colonial aims of disciplining and managing the population.”

Historian at Oxford University, Thum Ping Tjin, affirms this in an e-mail conversation with TheHomeGround Asia: “Modern racism in Singapore started when Sir Stamford Raffles colonised us, and imposed both economic elitism and European notions of ‘race’ and ‘gender’ upon us,” he says. “European colonialism relied upon a racial hierarchy to justify selective rationing of opportunity and monopolies of power – ‘divide and rule’.”

According to Zarine L Rocha, who was a sociology research scholar at the National University of Singapore (NUS) when her article Multiplicity within Singularity: Racial Categorization and Recognizing “Mixed Race” in Singapore was published in 2011, governing this nation along racial lines only “crystallised intergroup boundaries [and emphasised the] differences and inequality” among races. Prior to this form of governance, fractions had already existed “between and within Chinese, Indian and Malay populations.”

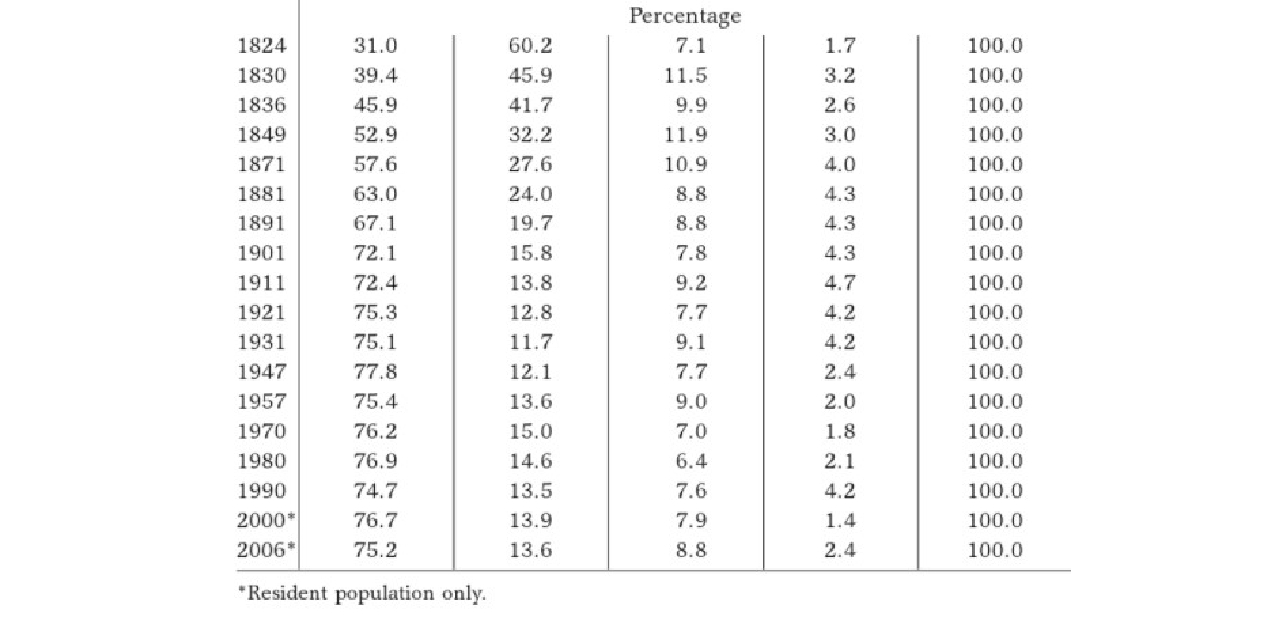

In the next steps to organise Singapore’s racial groups and the types of jobs that they started to take on, the British drew up a land-use plan for urban development, outlining areas for economic activities, and allocating land for the various racial groups.

In doing so, they segregated the town into districts where specific racial and occupational groups would occupy.

The land was divided among the four main groups – Europeans, Chinese, Malays and Indians. Dr Rocha argues that the racial ideology that Sir Raffles subscribed to was used in “justifying key economic and political imperatives”. They were operationalised in a few ways. She writes “Racially defined groups were separated occupationally, based on the stereotypes regarding “inherent” predispositions of each race”. The Europeans still held the roles of governing and were regarded at the top of the hierarchy.

Tumultuous fault lines along race during Singapore’s time in the Federation of Malaysia

Fast forward to 16 September 1963, when Singapore joined Malaysia to form the Federation of Malaysia. It was a challenging time as the two main political parties, the People’s Action Party [PAP] and the United Malays National Organisation [UMNO], vied for influence in the Government.

The PAP fought for a ‘Malaysian Malaysia’, where the country belonged to its citizens, regardless of race, and not to Malays. UMNO, however, disagreed and felt that ‘Malay dominance’ should remain. Both parties were soon accusing each other of ‘communal prejudice’, which stemmed from the disproportionate Malay and Chinese population.

Tensions intensified, culminating in the race riots of 1964, which took place on 21 July and 2 September. The riots continued periodically for weeks, and despite the imposition of curfews and the deployment of the military, law and order was only fully restored on 14 September.

The racial disturbances of 1964 played a pivotal role in leading Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman in believing that separating Singapore from the Federation would be the best way forward. At 10am on 9 August 1965, Singapore’s sovereignty was declared over the radio.

Public policies shaped by four main races in the building of Singapore

Emerging from racial and religious conflict, a newly independent Singapore sought to form a Singaporean identity among the largely diverse migrant population. The Government of the day attempted to do so by recognising four main ethnicities – Chinese, Malay, Indian and Others, as distinct but equal in the formulation of social policies.

Several public policies based on the CMIO model were enacted, such as the policy of mother tongue bilingualism, Ethnic Integration Policy [EIP], and group representation constituency [GRC].

Singapore’s CMIO model, or ‘social formula’, was effective in Singapore’s formative years, and “provided the PAP with the political and ideological advantage to take a neutral stance towards all racial groups’, writes social psychologist Geetha Reddy in Singapore: State and Society, 1965-2015. The model sought to demonstrate fairness or meritocracy, where through an absence of discrimination, the rights of minorities were protected.

But it has been argued, however, that there is a social cost in using the CMIO model, due to a disappreciation and lack of recognition of sub-ethnicities within the four main categories.

“The multiplicity within each of these categories is not acknowledged by the Government, and these differences with the categories, as well as between the categories are essentialised,” notes Dr Reddy, who disclaims that essentialism is oppressive; but that it oversimplifies race and identity, which ironically eradicates multiracialism and multiculturalism.

She uses an example of Indians: “They are divided by place of origin [Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Sri Lanka], language [for example, Tamil, Telugu, Punjabi] and religion [such as Syrian Christian, Hindu, Muslim].” While essentialising groups is vital for the effectiveness of government social policies, what the manmade classification of race in Singapore does is to shape the way we perceive, and influence the way we feel about one another: “In the collapse of differences within a category, certain groups became invisible,” she elaborates.

Essentialist thinking, writes Dr Reddy, “guides our psychological processes” to attribute casual stereotypes to social groups in order to understand and “rationalise their behaviours”. Hence, when racial classes are operationalised, the make-up of each group gives rise to the accentuation effect, when “similarities among one racial category are perceived as greater than they actually are,” she argues, “differences between members of different racial categories are perceived to be greater than reality, as well’.

Ethnic Integration Policy

The EIP, or commonly known as the HDB (Housing Development Board) ethnic quota, was introduced in 1989 to integrate ethnic groups into a community, and to prevent racial enclaves from forming.

On HDB’s website, it states that the EIP is “to preserve Singapore’s multicultural identity and promote racial integration and harmony.” It attempts to achieve this by implementing quotas at an HDB block or a neighbourhood so that the ethnic composition of Singapore is balanced.

In a debate in Singapore’s Parliament on 6 July, National Development Minister Desmond Lee provided a larger picture of how the EIP prevents racial concentration in one precinct.

“If you have neighbourhoods predominantly of one ethnic group, that will cascade into pre-schools, into our national school system, the services in the heartlands, the shops, the markets, the hawker centre food choices,” said Mr Lee. “They will adjust to reflect the proportions of the clientele in the neighbourhood.”

But Leader of the Opposition Pritam Singh said that his Workers’ Party aims to remove the EIP, one day, after the country achieves a state of being race neutral. One of the reasons Mr Singh is calling for the EIP to be revisited is due to the economic loss to minorities, who have to lower the market price of their flats, “penalising them in the pocket when they have to sell their flat,” he said.

“By minorities, I mean not just racial minorities (but) those who are affected by it, including Chinese, Malays… and this may perversely interact with the stated objective of the policy of racial harmony, thereby breeding resentment amongst those who are affected by the policy,” elaborates Mr Singh.

Other reasons to overhaul the EIP is the impact of mixed marriages, and immigration into Singapore, which results in families living in HDB flats who fall outside of the CMIO model of ethnic classification.

Group Representation Constituency

The GRC system divides Singapore into electoral divisions, and was introduced in 1988 after amendments to the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore, and the Parliamentary Elections Act. This system was implemented to ensure minority representation in Parliament, where at least one of the Members of Parliament in a GRC must be a Malay, Indian or another minority in Singapore.

Critics of the system argue that this policy of tokenism emphasises the consciousness of each other’s races, which defeats the aim of achieving a race-blind society. In addition, both the majority and minority of a GRC may harbour doubts about whether the candidate of a minority race was fielded due to competence, or the requirement of inclusion.

In a Facebook post on 26 June, in response to Finance Minister Lawrence Wong’s speech on racism, Mr Singh said that “it is worth questioning whether the majority of Singaporeans today will inevitably vote along racial lines”, because of the GRC system.

Back in 2013, former Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong had challenged Singaporeans to determine Singapore’s future values. He asked, “Should we have more cosmopolitan values in society? Because that is what we are now, more cosmopolitan. Or do we revert to just merely Singaporean, meaning Chinese, Malay, Indian and Eurasian?”

Sharon Siddique, who was a Visiting Professorial Fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew Centre for Innovative Cities when she spoke at the IPS Conference on Civil Society in 2013, said that the future of ethnic-based civil society would depend on how the CMIO model evolves as society grows more complex. In conclusion, Dr Siddique suggested that Singapore might find it harder to stick to the CMIO model in the future, due to a greater cosmopolitanism. It would be unable to contain Singapore’s global aspirations, which it was not designed to do.

Several of the arguments above were highlighted in 2010 when the then UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance was invited to Singapore by the Government.

In his report, the UN Special Rapporteur Githu Muigai acknowledged some of Singapore’s initiatives to maintain racial harmony, but noted that as a mature and educated society, Singapore could afford to loosen restrictions on free speech, and encourage open discussion on issues related to race and religion.

Most notably, he explained that the inclusion of race on the identity cards highlighted racial differences and contributed to racially based policies, which then led to racial discrimination. He added that as self-help groups are organised on ethnic lines, individuals from multicultural and inter-racial marriages may find it a challenge to access help. On the creation of GRCs to ensure that minorities receive equal political representation, he argued that on the contrary, the policy had ingrained the status of the minority community in Singapore, and furthered their institutionalisation.

In response to Mr Muigai’s report, the Singapore Government disagreed with its findings and recommendations, and stressed that “the principle of meritocracy is the basis of Singapore’s success and will continue to serve as the core value of our society.”

On discussing sensitive issues, the Government stressed that while “race, language and religion will always be sensitive issues in Singapore,” it does not mean that they cannot be discussed. In fact, it explained, “A balance must always be struck between free expression and preservation of racial and religious harmony.”

Increasing instances of racism and xenophobia in Singapore, and not only between races, but inter- and intra-race too

Racism is an interactive social issue that Singapore continues to battle. Some of the more subtle forms include landlords denying rentals to a particular ethnicity, minorities being bullied in school and at workplaces, and prejudice towards mixed-marriages.

Others take a more tangible form when employers supposedly reject applicants based on their race or religion. A 2019 study on hiring practices involving 171 Singapore-Chinese undergraduates was conducted by Peter Chew, Senior Lecturer in Psychology at James Cook University in Singapore. He found that on average, the participants saw Malay applicants as less competent, less suitable for the job, and indicated a lower salary than Chinese applicants with the same qualifications. These findings allude partially to the possibility of why Malay households have a”‘significantly lower median monthly household income compared to Chinese and Indians in Singapore.”

Whereas when it came to Caucasian applicants, the focus group seemed to exhibit Pinkerton syndrome, which is defined as “the preference for Whites, because of the positive stereotypes associated with them, such as being novel, interesting, socially refined, and intelligent.”

Institutional racism may also be a precursor to social racism.

Research has found that certain campaigns, such as the Speak Mandarin Campaign for Chinese only, but not for other mother tongues, emphasised the consciousness of a majority and minority race. Primary School English textbooks in the 1980s appeared to illustrate the stereotype that Malays were in low-paying jobs, such as road-sweepers, while the Chinese held skilled jobs, such as doctors.

With the recent spate of alleged racist attacks on Indians, the question that hangs over Singapore is whether the debate on CECA (Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement was partially responsible for it.

Inter-race racism exists too, that is the prejudice towards another race, majority or minority.

A Malay woman was jailed four weeks on 23 June for spewing racial slurs at an Indian woman on a public bus, last year. Both are minorities in Singapore.

On 14 August 2019, the Nair siblings (influencer Preeti and musician Subhas), were given a conditional warning for a rap video that they produced, which questioned a controversial ‘brownface’ advertisement, where an ethnically Chinese actor allegedly darkened his skin to portray characters of different races. Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam called Nairs’ video an “attack [on] another race” and said it was “offensive content”. While the creators of the advertisement were only given a stern reminder by Info-Communications Media Development Authority, who assessed that it did not breach the Internet Code of Practice.

Most recently, a Caucasian teen was seen on a TikTok video repeatedly calling the Singaporean-Chinese host ‘chink’ and ‘zipperhead’, which are racist slurs for Asians. So although Chinese are a majority in Singapore, they face racism by other races too.

No matter inter- or intra-race, racism has inevitable social costs.

Associate Professor Tan Ern Ser, a sociologist with the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at NUS concurs. He says that racism “produces tension and conflict, and in turn [is] a hindrance to social interactions, integration, and consensus on values and issues essential for inculcating a common identity and purpose.”

Open dialogue a catalyst to insensitivities or a solution?

How does Singapore effectively tackle racism then?

In a 2016 survey of 2,000 Singaporeans, between 64 and 66 per cent of respondents said that an open dialogue and honest conversation on this issue will “cause unnecessary tension”. While 53 per cent also believed that racism was no longer an important problem, which will decrease the perceived necessity to talk about racism. Also 46 to 70 percent of those surveyed were not “supportive of race-based information [about crime, educational performance, social problems, and so on]”, as they felt that it could expose racial disparities, exacerbating racism, racial disharmony and unhappiness.

This fear and reluctance to talk about race and racism pose a threat to establishing understanding and racial harmony, since discussing racial issues is a “useful starting point”.

Associate Professor Chong writes that an open dialogue “[encourages] greater reflection about race relations”, which in turn encourages change and builds mutual trust, as well as develops the “shared vocabulary for dialogue and explaining differences in ethnic experiences.”

Transparency and availability of information are also useful in forming the first line of defence against racism, argued Mr Singh in Parliament. This could help to “quell, or at least nip some of these issues in the bud when they start moving into the realm of xenophobia or nativism,” he explained.

But, Finance Minister Lawrence Wong has cautioned that Singaporeans “should not adopt the worst interpretation on every perceived slight or insensitivity”, because he notes that “taking this position when calling out racist behaviours will lead to misunderstanding and ultimately make things worse”. Such conversations, he says, “can be inflamed and things can easily spiral into negativity, racial tensions, or worse, violence.”

Look out for the second part of this series on racism, where TheHomeGround Asia explores the question of whether the different perspectives of the various ethnicities around racism in Singapore are at odds, and if this would hinder society achieving racial harmony.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.