Efforts to document integral parts of Singapore’s cultural heritage have resulted in the Intangible Cultural Heritage inventory, an initiative by the National Heritage Board that documents and identifies key parts of Singapore’s culture, including heritage businesses and performing arts. Some of these traditions face the possibility of disappearing from Singapore’s cultural landscape. TheHomeGround Asia speaks to practitioners from local heritage trades and performing arts to learn more about the challenges they face in preserving these traditions in Singapore, and how they have kept up with the needs of younger customers, particularly with the pandemic as a backdrop.

Entering Ban Kah Hiang Trading feels like a step into the past, with its bold red signboard and simple wire racks holding various paper offerings. At first glance, the joss paper shop looks like any other, with joss paper and boxes of joss sticks stacked neatly on shelves. But a few things catch the eye: A paper bird cage dangles overhead, which upon closer inspection reveals a remarkably lifelike bird, complete with feathers. This is one of several unique offerings that third-generation owner Alex Teo has come up with.

Founded in the 1950s by his grandfather, Ban Kah Hiang Trading is one of Singapore’s heritage trades, many of which are traditionally family-owned. Such businesses form a part of Singapore’s Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH), which includes the traditions, practices and expressions of local culture that are passed down through generations.

Mr Teo shares that Ban Kah Hiang Trading traces its roots back to his grandfather’s incense factory, which closed in the eighties due to high operational costs. Following his grandfather’s retirement in the early-90s, Mr Teo’s father converted Ban Kah Hiang into a wholesaler and supplier for incense and joss sticks.

At 28 years old, Mr Teo stepped in to take over the business in 2016, leaving his corporate job as a medical claims assessor. The young Mr Teo found innovation key in keeping up with consumers’ needs, which soon reflected itself in uniquely Singaporean offerings, such as hell bank notes made to resemble local currency.

According to Chinese ancestral worship customs, incense sticks and joss paper – otherwise known as kim zua – are burnt as offerings to deceased loved ones on special occasions, such as funerals and the Hungry Ghost Festival. Offerings are given to ancestors with the belief that they will appease the spirits of the deceased, as they will be received and used in the afterlife, with hell bank notes and joss paper being regarded as forms of currency.

While offerings used comprise mainstays like joss paper, hell bank notes and incense sticks, shops like Ban Kah Hiang Trading have added their own innovative touches, providing a wider range of offerings over the years. For instance, paper effigies of hotpot sets, bubble tea and Chinese jelly desserts – all familiar favourites in Singapore’s diverse food culture – line the racks, along with the little red dot’s iconic fruit: durian. Keeping current, there is even a pandemic-friendly mask kit, complete with handheld thermometers, masks and hand sanitiser.

Some have patronised his business after receiving messages from deceased loved ones in their dreams. Mr Teo recalls how a customer once told him that his late brother had visited him in his sleep to ask him to buy a paper effigy of a bird cage from his store.

He jokingly attributes this to the effectiveness of mobile phone paper effigies: “Maybe in hell or whatever, the WiFi, handphone, all working, got network. Maybe also scrolling Facebook, see my shop and ask you to come and buy,” he quips.

One of the most unique requests he has received was to stock petrol for the dead: “Customers would think, ‘There is a car then no fuel, how?’,” he shares, and later solved this dilemma by developing an effigy of a full-service petrol kiosk.

Pet paper effigies are another product sold at Ban Kah Hiang Trading. These come complete with pet food and even kennels, a testament to Mr Teo’s attention to detail, ensuring that furry friends are well taken care of in the afterlife.

For Say Tian Hng Buddha Shop, finding products to cater to new audiences has been a too-real battle. Ng Tze Yong, fourth generation owner, explains that while their products centre on the crafting of effigies for religious purposes, they continue to find new business opportunities. For instance, his family is reaching out to secular and international customers, developing new products that redefine the way they are valued.

“Currently, the effigies are displayed in temples and home altars. But can we also redesign them for homes in London and offices in New York?” he questions.

Say Tian Hng (meaning ‘heavenly garden’) Buddha Shop is Singapore’s last surviving shop for effigy-making, and has been handmaking Taoist effigies since its inception by Mr Ng’s great-grandfather 125 years ago. The business is currently run by Mr Ng’s grandmother, Tan Chwee Lian, and his father, Ng Yeow Hua.

Mr Ng points out that passing artisanal skills on to younger practitioners is tough, as heritage practitioners have to prioritise their businesses, leaving little time to impart skills to potential practitioners.

“You have a struggling business to keep afloat. You got rent to pay, food to put on the table. So often, [you] don’t have time to train [new apprentices],” he explains.

Yet another barrier that older practitioners face in preserving their trades, says Mr Ng, is the reluctance to pass it on to potential successors who are not family members. He attributes this to a tendency to keep trade secrets within families, a legacy of the intense competition of flourishing heritage trades in the past.

But other heritage art forms deal with a different set of issues, as is the case for Sri Warisan Som Said Performing Arts Ltd.

First established in 1997 by renowned Malay dancer and Cultural Medallion recipient Som Said, Sri Warisan Som Said Performing Arts Ltd is one of the few remaining performing arts companies in Singapore that performs wayang kulit, a traditional form of shadow puppet theatre. Sri Warisan’s performers are also trained in other traditional art forms, such as Bangsawan, a form of Malay operatic theatre.

At present, the company is led by Mdm Som’s son, Adel Ahmad, who specialises in introducing wayang kulit to younger generations.

Mr Adel explains that Sri Warisan has trouble finding artisans who have the craftsmanship to create the paraphernalia needed for wayang kulit performances.

“We don’t have people who make the screen – the carving out of the screen anymore. We don’t have people who make the characters (puppets) because you need to have [materials like] buffalo skin, ivory,” he says, adding that materials such as wood and fibreglass have been used in the crafting of puppets in recent years.

Yet another problem is hiring performing artists who are willing to commit themselves to performing, as the process of training performers requires a lot of time and patience.

“Not many people want to make this a way of life,” he explains. “So we have to compromise. It doesn’t have to be a full time [focus] on puppetry. You can [be] a musician or a dancer, but hopefully you will learn about puppetry as well.”

Language barriers can also prevent heritage businesses like Sin Ee Lye Heng from relating to contemporary audiences through traditional art forms. Founded in 1974, the company is Singapore’s last Teochew Opera street puppet troupe.

Third generation performer Christine Ang, whose grandmother started Sin Ee Lye Heng, explains that many people from younger generations do not understand the form of Teochew used during their performances, as this tends to differ from the variant of the dialect that is commonly used in more informal contexts, such as day-to-day conversations.

“I think the most important is the subtitles,” Ms Ang says, explaining that if the audience does not understand what is being said, they would be unable to appreciate an interesting performance.

Her mother, Tina Quek, who helms Sin Ee Lye Heng, is also worried about the long-term prospects of her family’s business. She explains that Sin Ee Lye Heng has had fewer performances since the pandemic began, and wonders whether this will be the second consecutive year that her troupe would be unable to perform for the Hungry Ghost Festival.

“With Covid going on for so long, we don’t know how we can continue to perform,” she says, concerned about how it would affect her troupe’s morale and skills.

“We may forget some of the skills we picked up if we haven’t performed for a long while,” she laments. “I worry that my troupe’s confidence and team morale will fall…They still look forward to putting up performances.”

Mdm Quek is also wary of what this spells for the future of Teochew Opera performances in Singapore.

“I’m afraid that people who usually invite us to put on performances may get used to spending the Hungry Ghost Festival in a more subdued manner in future, due to the pandemic,” she says. “This may reduce the number of opportunities we have to perform in the future. I hope that doesn’t happen.”

Paving the way for the future

“Storytelling and meaning-making is a big part of how we are trying to reinvent the shop for the future,” Mr Ng muses. “Because every effigy is actually a story.”

To reach out to younger audiences, Say Tian Hng Buddha Shop hosted Design for Deities last year, an international competition that challenged designers to reimagine a traditional statue of a Monkey God for an international, secular audience. They are now working with the winning team to put the design on crowdfunding site Kickstarter.

Mr Ng shares that his family is also keen to create a digital inventory comprising 3D scans of the shop’s masterpieces that were carved decades ago by artisans, who have since passed away. He thinks this will aid in replicating these pieces in the future.

Hosting tours as an Airbnb Experience is yet another way that Say Tian Hng Buddha Shop has kept up with today’s customers. What started as Mr Ng’s thesis project at a New York design school in 2015 led to monthly tours that are usually sold out. Four generations of the family, from Mr Ng’s grandmother to his young daughters, are involved.

He adds that approximately 80 per cent of the tour’s attendees were local, which surprised the Ng family, as they had assumed that tourists would constitute the majority of attendees.

“But that was encouraging, because it reflects a resurgence of interest among the people to whom this should matter most,” he says.

Now he is planning to hold the tours more than once a month, increasing it to maybe two to three times a week via a docent training programme. There is also the idea of creating a menu of different tours curated around various deities.

“Imagine it as a Netflix of tours focusing on different deities,” is how he describes it.

While tours are temporarily suspended, Mr Ng shares that his family aims to resume hosting them in June.

Mdm Quek explains that she would be keen to teach younger generations and the public about the traditions of Teochew Opera puppetry.

“I wouldn’t want to conduct lessons in Community Centres,” she says. “I would like to have a space for us to keep and display all our props and paraphernalia from performances, be it Teochew Opera performances or puppetry performances, so we can showcase these [essential parts of Teochew Opera culture] to help people understand what they are.”

She cites the example of wooden trunks used to store costumes and materials from their performances: “Although we don’t use them much these days, I can’t bear to dispose of them, because these are a part of our traditions, and they have their own unique history,” she shares. “Our performing troupe is over forty years old, but the trunks themselves are almost a hundred years old.”

Meeting the needs of modern consumers

In his efforts to reach new markets and consumers, Mr Ng walks a fine line between innovation and tradition. He imagines the Say Tian Hng Buddha Shop of the future as a CD shop, where there are different sections for different tastes.

“For those who love tradition, there is a classical section. For those who love pop, there is a contemporary section. And so on and so forth,” he explains. “At the end of the day, we are selling the same thing, which in our case is Chinese culture and mythology. The whole point is to connect.”

But he warns of the need to be respectful, because artistic expression can be misinterpreted: “After all, we are a heritage business and the devotees who are our current customers will continue to be our core,” he says.

Catering to younger customers has pushed Mr Teo to modernise Ban Kah Hiang Trading’s traditional products by putting a spin on them, like adding jasmine and lavender scents to their joss sticks.

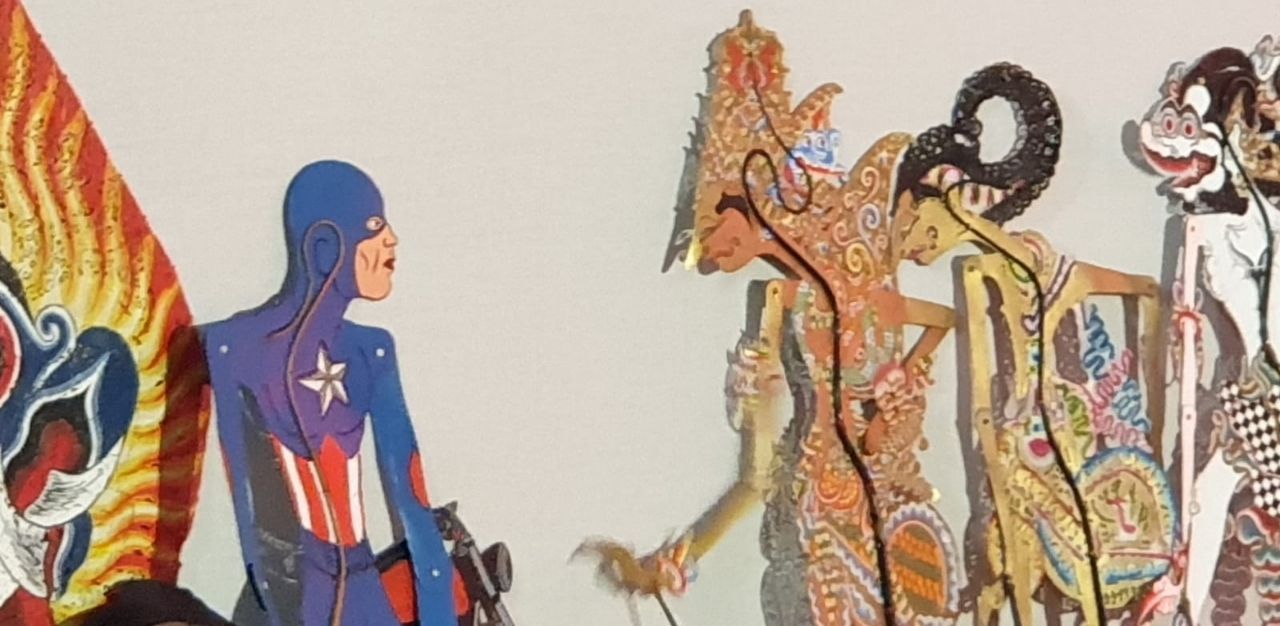

While Sri Warisan has found a way to connect with younger audiences by incorporating superheroes into wayang kulit, which have added a twist to classic tales like the Ramayana. In this story, Prince Rama attempts to reunite with his wife, Princess Sita, who was captured by an evil king.

“Once the evil king is with Princess Sita, we end the story – that is the classical traditional part. But then we have a twist: who helps to save Princess Sita and fights the evil King Ravana? It’s actually Superman, and then the Avengers – so Hulk comes in, Thor, Captain America,” he laughs. “But after that, we bring them back to the traditional element [of] wayang kulit.”

What lies ahead for heritage businesses

Mr Adel is hopeful for the future of wayang kulit in Singapore, as he sees growth in the uptake of wayang kulit in arts education programmes.

“More teachers are aware [of] the benefits of having something like wayang kulit to teach students things like light, shadows, sound, characters, facial expressions… The possibilities are endless,” he enthuses.

Sri Warisan has also presented wayang kulit performances at community outreach programmes such as Arts In Your Neighborhood, and has been invited overseas to present Singapore’s unique style of wayang kulit.

As Say Tian Hng Buddha Shop is Singapore’s only remaining Taoist effigy-making business, Mr Ng admits that there is pressure to keep it going, but adds that it is also a blessing.

“The craft is like a connection to my forefathers. It passed down through the generations, one after the other, and now, we have the opportunity to receive it and share it with others.”

The odds are stacked against them though. With his grandmother and father nearing 90 and 70 respectively, time is still the biggest hurdle, especially for a craft that takes years to master.

“But the most important thing is to at least try. Because if we don’t try, it ends. There is no way after that to resurrect it,” he warns.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.