Since the first batch of Covid-19 vaccines rolled out in Singapore in December 2020, a rift between people on both sides of the decision to be inoculated began and is set to widen over time.

From the initial narrative to the public in December 2020 by then Health Minister Gan Kim Yong that vaccination is a personal choice which the Government will respect to the vaccination-differentiated safe management measures (VDS), there has since been the gradual tightening over several rounds, with the most recent banning unvaccinated workers from entering their workplaces.

While the VDS was initially understood as “necessary” to encourage everyone, including those who are holding out to get vaccinated, the latest ruling has the potential to deprive them of their livelihoods. This begs the question — have these measures become overly punitive for what is essentially individuals exercising their rights to choose?

Why do some persistently hold out against getting inoculated?

First, it is important to establish that I believe in the efficacy of vaccines and that the benefits far outweigh the risks. I am triple-vaccinated and have taken each jab at the earliest opportunity possible. However, instead of deprecating those who choose to delay their vaccinations or to remain unvaccinated, I prefer to see from their point of view and seek to understand the reason for their reluctance.

According to the authorities, there are about 120,000 unvaccinated adults, the majority of them by choice. Understanding the demographics of this group of people and the reasons for their hesitancy would be an important first step to finding a solution to keep everyone in Singapore safe.

There is this stereotype that vaccine holdouts are irrational conspiracy theorists who reject mainstream science and cannot be reasoned with. A quick search online on vaccine conspiracies pulls up more modest tales such as causing infertility to outrageous ones such as containing nanobots that can one day be used by the authorities against the vaccinated.

However, none of the four individuals I spoke to fit those stereotypes. In fact, it was quite the opposite; they were all aged between late 20s and early 30s and well-educated. They shared their concerns and reasons for putting off getting inoculated for as long as they could.

Zan and Mik, a young couple who declined to give their full names for fear of reprisal, are very concerned with how the Covid-19 vaccines were rolled out in a relatively short period. They also have reservations about the long-term side effects of the mRNA vaccines as they felt the technology had not been “tested and proven sufficiently in longitudinal studies to be certified as safe”.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, the mRNA vaccines teach our cells how to make a protein that will trigger an immune response inside our bodies and like all vaccines, the mRNA vaccines benefit people by giving them protection against the Covid-19 without getting sick.

In addition, Zan and Mik have plans to start a family in the “near-to-middle term”, and they are worried that getting themselves inoculated may have a negative impact on their future child. It was a risk they are not prepared to take as they are still unconvinced by the studies done so far.

But when the Sinovac vaccine, which uses the more traditional inactivated virus method, arrived in Singapore, they continued to hold out, worried about its low efficacy rate and were concerned with the fact that its risk of side effects outweigh its benefits.

In their words, they would “rather risk getting infected with Covid-19 than to risk the side effects”, because, according to them, one might not necessarily contract Covid-19, but if the vaccines do cause severe side effects, “they would be irreversible as we would have already been injected”.

However, by late 2021, Mik’s employer required all the staff to be vaccinated to continue working. Faced with the prospect of job loss, Mik had no alternative but to be inoculated despite her doubts.

The couple made a joint decision to take the Sinopharm vaccine, a traditional vaccine with a higher efficacy rate of 79 per cent than Sinovac’s 51 per cent.

It should be noted that both Zan and Mik are not against vaccinations per se, rather, they just wanted to wait for a vaccine which they are comfortable with. After all, everyone has a different tipping point when it comes to the risk-benefit consideration. Zan and Mik had originally wanted to hold out for the Novavax Covid vaccine, which offers at least 90 per cent efficacy and utilises a technology which they believe in, but it has yet to arrive in Singapore to date.

Zan and Mik say that the VDS closes in on the unvaccinated to such an extent that “vaccination might as well be compulsory, instead of telling the unvaccinated that they have a ‘choice’”.

Linus, who also refuses to give his real name for fear of payback or being trolled online, remains unvaccinated. The professional in his early thirties, maintains that he is not against vaccination as he has taken numerous other vaccines over the years. His main gripe is that the Covid-19 vaccines are “rushed out” in record time under intense global pressure, and the limited number of trials is simply not enough to convince him that it is safe.

Rin, Linus’s wife, shares his sentiments. Both of them are unvaccinated by choice until the VDS tightens, barring unvaccinated people from entering malls. As Rin is in the retail business, it became unfeasible to remain unvaccinated as a daily Antigen Rapid Test (ART) is needed before the start of each work shift. The daily ART took its toll on Rin. “I have a sensitive nose and the daily tests caused my nose to bleed,” Rin says.

Unable to take the physical stress, she gave in and got inoculated with the Sinopharm vaccine. But the bitterness of being between a rock and a hard place remains. Linus on the other hand, manages to hold out against getting vaccinated as he is currently working from home.

But he is not sure how long he will be able to keep his job should working from home no longer be an option. The latest round of measures is prohibiting unvaccinated workers from returning to the workplace from 15 January, and giving companies the right to terminate them if they are unable to do their jobs at the workplace.

Linus says he can accept all the other VDS such as requiring the unvaccinated to pay out of pocket for their Covid-19 medical bills because those are inconveniences he has to bear for exercising his right of choice; but the decision to deny him of his job has, in his opinion “crossed the line”.

Questions abound

One cannot help but recall how the whole account of masks has shifted over the course of the pandemic, from discouraging people from wearing them to a mask mandate that took immediate effect.

Has that same shift taken place over vaccinations too? Given the current strict VDS in place, is there a real “choice” over vaccination when people’s livelihoods can be legally taken away from them?

There are also many questions to be answered, such as who the VDS are meant to protect — the vaccinated against the unvaccinated or the other way around? Or can it be between the unvaccinated by choice against those who cannot be vaccinated? What about the unvaccinated from themselves?

Has the intention of the VDS changed from “encouraging” vaccination take-up rates to outrightly punishing those whom the government had said they would respect the decisions of?

Has there been any attempt in the first place to reach those who choose not to be vaccinated so that their concerns can be addressed before the stick is wielded?

Despite being in favour of vaccination, I too, wonder if the policies have gone a step too far by depriving those who chose otherwise of their livelihoods.

The perils of pushing vaccination too far

The bigger issue here, is the danger that the VDS might be seen as discriminatory and create unnecessary animosity between those who are jabbed and those who are not.

It is easy and tempting for those who view getting vaccinated as a moral responsibility to lump all who are still refusing or holding off getting jabbed as being in the same group as the notorious, ideological anti-vaxxer movement in the United States and France.

One such active anti-vaxxer was Singapore-born actress turned writer Cirsten Weldon. Weldon, who was also an interior designer, focused on attacking vaccines and other efforts to fight Covid-19 and said “those who get vaxxed are idiots” died in a hospital in California (CA) on 6 January from the virus. She had, at the beginning of January, shared a photo of herself undergoing oxygen treatment, explaining that she “almost died at hospital in CA from bacterial pneumonia”.

Already, the unvaccinated have been labelled as selfish and a danger to themselves and everyone else. In return, the vaccinated have been called self-righteous and behaving like an angry mob.

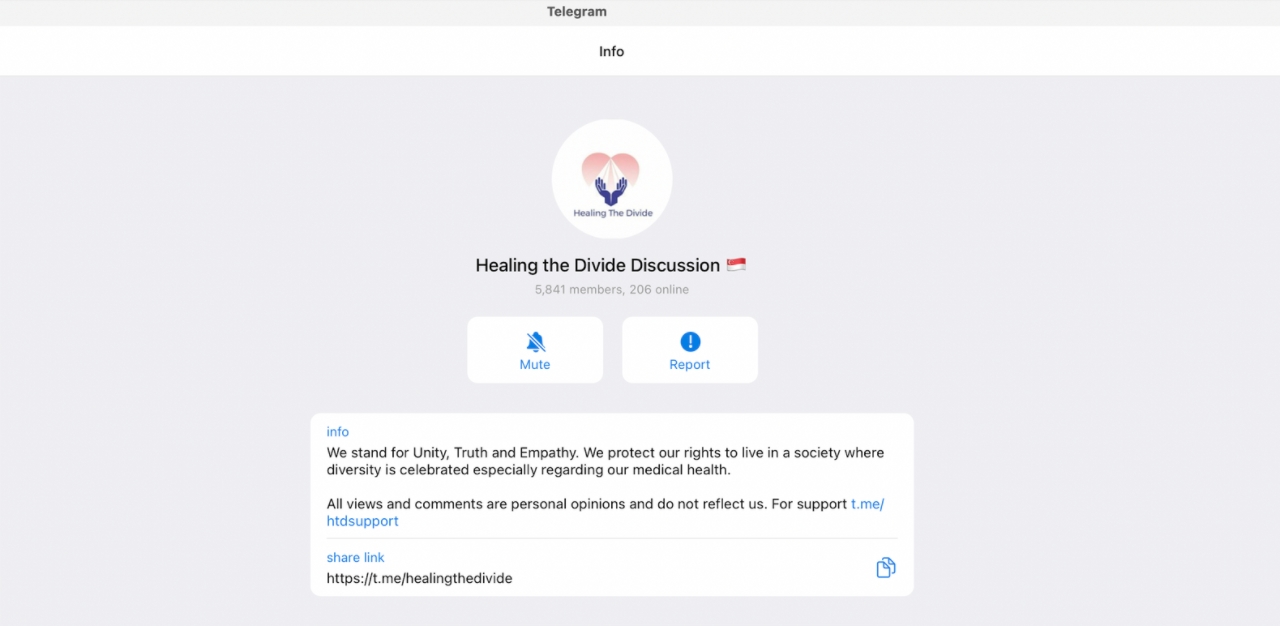

The recent saga involving anti-Covid-19 vaccination group Healing the Divide and its founder, Iris Koh, has highlighted the slippery slope of pitting one segment of society against another. Despite attracting controversy and legal action over the publishing misleading information and falsifying medical records, the group still managed to garner close to 6,000 members to its Telegram group.

And when the policies are tightened too far, those who feel coerced may view the Government as overly authoritative.

Policies can be tweaked ever so strictly to increase the vaccine take-up rates and people may be left with no other viable options than to submit to the pressure and get themselves vaccinated. For these people, their trust in the Government would have been diminished.

Surely, we want to come out of the pandemic stronger, and not put the disease behind us at the cost of some losing their trust in the leaders and in the society.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.