(Content warning: Depression and suicide)

Shubhra Shastry had just put her six-month-old daughter to bed, but in the brief moments of peace that followed, she found that she was unable to settle her mind. While her daughter slept on, blissfully unaware, Ms Shubhra found herself lost in a downward spiral of emotions.

“I couldn’t hold myself together,” she recounts. “I felt so all over the place in terms of my thoughts, and my energy. I was physically shaking to the point that I had to sit down. And then, it became this unleashing kind of crying.”

What followed was a barrage of thoughts that she was unable to control: “I was [thinking], what if I just jumped off the building? But then, I thought, no one could help her [her daughter]. So should I just take her with me?”

“Your mind goes into this weird sort of dark place of self-loathing and sabotage,” she explains. “It is thinking, ‘I need to end the pain now, and what’s the fastest way to end pain now?’ And because it doesn’t know where the pain is, it’s all over – the mind, the body, the body shaking, the tears, the breathing, everything. It’s going, ‘You need to do something to stop the pain’, and the first thought goes towards suicide.”

And that, she recalls, “scared the living bejesus” out of her.

“What if the thoughts get so bad that they overtake all reasoning?… I may lose my mind because another part of my brain that I have no control over may take over, and I better stop that before it does,” she says.

In that brief glimmer of rationality, Ms Shubhra called her husband, who rushed home from work to be with her, as well as her parents, who were living abroad at the time, but booked a plane ticket to Singapore. It was only then that she could take a breath, safe in the knowledge that her loved ones would be around to keep her and her daughter safe.

While this one moment was Ms Shubhra’s breaking point, the incident did not arise out of the blue. Instead, it had been born from multiple factors converging.

The spiral into postnatal depression

Ms Shubhra’s breakdown had come after months of broken sleep and poor eating habits, and the neverending pressure of being a mother, topped with biological factors such as hormonal changes, and a past history of depression.

Having suffered from severe reflux during her pregnancy, Ms Shubhra was already having trouble sleeping before the birth of her daughter. This only worsened after her daughter was born: “The sleep was so bad, to the point that I was only getting two hours in a 24-hour period. I would only sleep from four to six [in the morning], when [Rahul, my husband,] would take the baby in a carrier and go for a walk.”

“It was a cascade of processes,” she explains. “Depression hits even stronger the more your body is under-rested. And because the balance of hormones is already out of whack [from pregnancy and breastfeeding], it’s just a domino effect.”

Ms Shubhra’s story is not reflective of all mothers who go through postnatal depression (PND, also referred to as postpartum depression).

Senior Consultant and Head of the Women’s Mental Wellness Service at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital Dr Chua Tze-Ern highlights that what Ms Shubhra experienced are potential risk factors for PND, and that many factors can play a role in contributing to the condition.

In particular, Dr Chua points out that a past psychiatric history is a significant risk factor, as is the presence of obstetric complications. Young mothers under 21 years of age and mature mothers are also at a higher risk of developing PND. Other stressors can include “marital difficulties, interpersonal problems, financial and workplace problems, and having insufficient support, which may accumulate to increase the risk of the development of PND.”

Risk factors can also vary depending on the individual, Dr Chua explains. For instance, some may find breastfeeding a stressful experience, while others may relish the experience as a way to bond with their newborns.

But while risk factors are aplenty, with some being outside of a mother’s control, there are measures that mothers can take to protect themselves.

Protecting oneself from postnatal depression

Dr Chua recommends three approaches to cultivate a healthy outlook towards motherhood.

The first is to appreciate the fact that life will be different once the baby arrives. She explains that this will help to “temper feelings like guilt, dismay, and self-blame during stressful periods,” which were the emotions Ms Shubhra experienced the moment she found out she was pregnant.

Despite being overjoyed by the news, she also says, “It felt like the pressure was on straight away. From this moment [pregnancy], I’m no longer for myself [only]. Even after she comes out, even until she’s 18, this is it. My [life of just being Shubhra] has ended, and that was quite overwhelming.”

The next approach to prioritise personal well-being is also vital in preventing PND, emphasises Dr Chua. She highlights that while a mother may think she is duty-bound to achieve success in and outside her home, the need to ensure she is physically and mentally well should not be forsaken. This includes having a balanced diet, getting adequate rest, as well as being kind and nurturing to herself.

Finally, Dr Chua underscores the importance of developing awareness and acceptance of one’s emotions. While societal expectation may dictate that having a baby is a happy and fulfilling affair, she points out that parenting is hard work, which entails struggle, stress and sacrifice. Thus, mothers should be able to express their tiredness, worry, and frustration, without being judged. Nor should they be blamed for not automatically knowing how to handle a baby, or for experiencing negative emotions.

Ms Shubhra adds that getting sufficient rest is of utmost importance, citing the lack of it as a key factor contributing to her PND. She shares that even though her daughter was sleeping well, she struggled with insomnia after months of broken sleep.

“I was still breaking down because my body didn’t know how to sleep anymore, so I was still rattled… I was jumping every single time [my daughter] made any sound,” she shares. “That’s not healthy, because your brain is not able to shut down.”

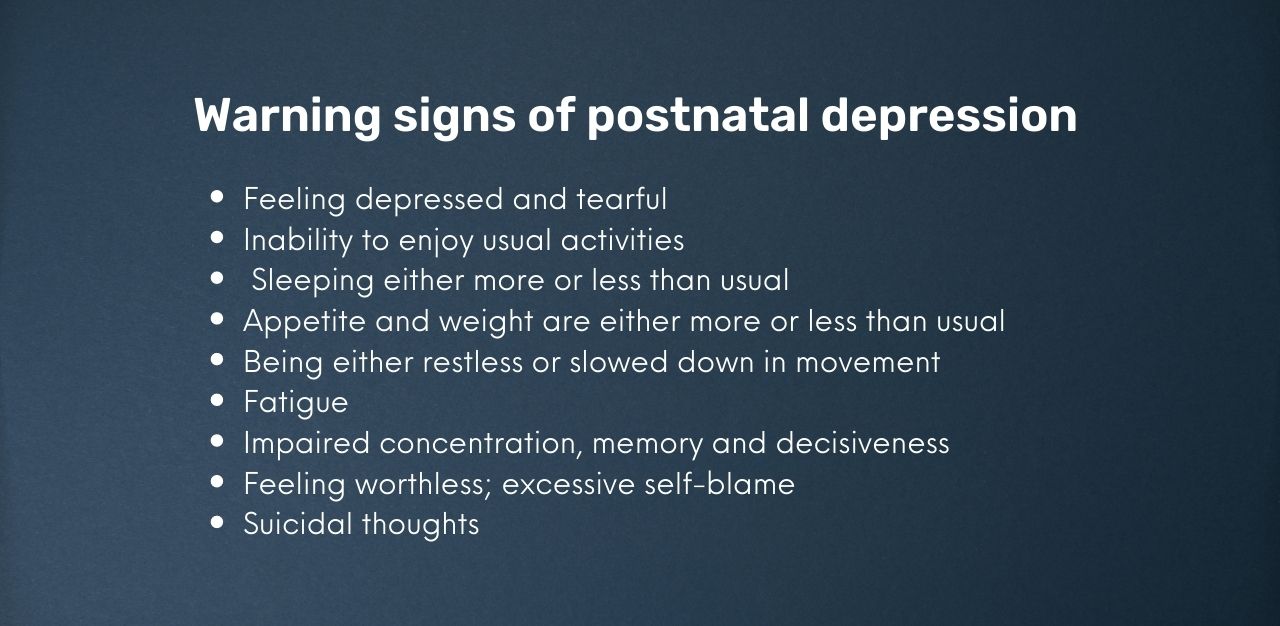

Caregivers surrounding the mother should also be attentive to warning signs and indicators that something might be wrong, and to get them help when possible.

They should also be cognisant of symptoms that can indicate severe depression, including confusion, auditory hallucinations, the presence of irrational beliefs, thoughts of harming the baby, or suicidal thoughts.

In such scenarios, Dr Chua emphasises that removing the baby from the mother should not be the automatic response. She clarifies, “Although severe depression increases the risk of suicide and infanticide, this outcome is fortunately rare. Most mothers with depression love their children deeply. In fact, their sadness, guilt and negativity often stem from the fear of not being a good mother.”

She continues, “We should do our best to improve, and not remove, the mother-child bond. Simply taking her child away will reinforce to a mother that she is indeed a bad parent, which will probably worsen her depressive symptoms.”

And while mothers have primarily been in the spotlight when it comes to discussions on postnatal depression, Dr Chua points out that fathers, too, can be susceptible, and should not be left out of the conversation.

In fact, she says that approximately one in 25 new fathers may experience some form of psychological problem, with depression being one of them.

Should fathers begin to experience symptoms that affect their well-being, functioning, emotionality, and ability to relate to others, Dr Chua encourages them to seek help as well. In the case of paternal depression, she clarifies that psychological support and therapy is the mainstay of management, similar to PND. In severe cases, medication may also be recommended.

Finding a supportive community

Having a support system is essential too, highlights Ms Shubhra: “Choose the most reliable person that you feel you can tell 100 per cent [of things to]…The last thing you need is to feel unsupported by the people around you,” she says.

It is a point reiterated by her husband, Rahul Shastry, who emphasises the need to be understanding of the mother’s emotions and potential fragility: “It’s a very sensitive period for the mother, [and so] it’s important for the family to understand what the mother really wants.”

Ms Shubhra agrees, citing instances of family members who would give unwelcome feedback or comments on how she was raising her daughter, which only served to increase the stress she felt.

“If you have family members that are not very supportive of anything you do, because they think it is going against what they did for you, and you’re [having to] manage their emotions rather than attend to the baby…that can be really, really tough,” she shares.

Adds Mr Rahul, “It’s all in good intentions, but maybe it’s not the right time and setting to bring up [your past experiences]. It doesn’t matter what experience you have, if the [mother] is not in a position to receive it, you’re just adding more chaos.”

Rather than offer unsolicited advice, he instead recommends “reading what is needed for the hour, so that they [mothers] get the support that is essential.”

He also suggests that partners be actively involved in childcare: “If both parents can equally spend time [with the child], it makes a world of difference in terms of connecting. Over time, it also helps in the relationship to showcase that you’re an equal partner in terms of caring for the baby.”

It also helps if mothers could lead as normal lives as possible: “It shouldn’t become that they are stuck, cooped up in a room,” he says. “It’s important that they can get back to normalcy, so that they can feel like a normal human being, and connect with a social self outside.

“Otherwise, you end up living in your own little bubble,” he cautions.

A need to talk about the downsides

Further, Mr Rahul opines that postnatal depression is not being addressed enough when talking about parenting, and hopes that all pre- and post-natal classes especially will cover such topics – on support systems for mothers, or who to reach out to when there is an emergency.

“No one talks about it, because it comes down to how society perceives [postnatal depression],” he says. “But if it could be normalised, it allows more people to speak a lot more openly about it.”

Mr Rahul also emphasises the importance of partners being open to each other, and healthcare providers, of their medical history, including psychiatric conditions: “That’s very useful because the gynae did speak to me about her history of depression, so she informed me separately to pay attention to her,” he says.

“[This] gave me some level of comfort and guidance on what sort of indicators I needed to look out for, and that really helps,” he adds.

Ultimately, he believes that while parenthood can be a celebratory affair, it is essential to speak about the struggles and reality too: “They can be caught up in a celebratory party, but at the same time, it’s good to provide a reality check that this [postnatal depression] can also happen, so just be prepared.”

Moving forward, and seeking help

In the end, when a safe space can be created for a mother to learn how to care for her child, and the mother is receiving adequate support (and medical care, if necessary), Dr Chua says, “The prognosis for maternal depression is excellent.”

For Ms Shubhra, her lowest point was also the beginning of her recovery. After calling Mr Rahul during her breakdown, she contacted her cousin, who is a doctor in Australia. He had recommended that she reach out to her gynaecologist, who was then able to refer her to a psychiatrist, who put her on medication to manage her condition.

The road to recovery might have been a long and arduous one, but with the support of her family and professional help, she has managed to rise above being depressed, after more than a year.

“Now, I see it as a blessing, because it made me wake up about a lot of things,” muses Ms Shubhra. “Looking back, [I realised] I put so much pressure on myself because I had these beliefs that I needed to live up to expectations [of being a good mother].”

She adds, “I’m really grateful for [the experience], because I know now what not to do.”

Resources and helplines if you need support

If you are, or someone you know is struggling, or just need someone to talk to, resources are available:

- Care Corner Counselling: 1800 353 5800 (Mandarin)

- CHAT webCHAT Service

- Fei Yue’s Online Counselling Service

- Institute of Mental Health’s Mental Health Helpline: 6389-2222

- KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital’s Women’s Mental Wellness Service: [email protected]

- National Care Hotline: 1800-202-6868

- Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800-283-7019

- Samaritans of Singapore: 1800-221-4444

- Silver Ribbon Singapore : 6385 3714

- TOUCHline: 1800 377 2252

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.