‘Keyboard warrior’; ‘Social justice warrior’; ‘Slacktivist’.

These phrases and portmanteaus are common insults thrown at the people who passionately advocate for the causes that are close to their hearts, in online spaces such as Instagram.

People have questioned whether those who practise digital activism and advocacy are getting any real change done. It is a concern shared by Kate Yeo, who runs @byobottlesg on Instagram, an account dedicated to sustainability and climate justice.

“Social media can also be an echo chamber,” she says, “in that the people reading my posts are already interested in sustainability, so I might not feel like I am making a huge difference through my social media posts alone.”

There are many who also dismiss Instagram activism as performative, that it is about saying the right things and virtue signalling; making activism pretty and easy on the eye.

Instagram’s interface, however, has allowed many activists to carry out their work of educating and raising awareness. Countless articles on social media marketing have pointed out that Instagram is primarily a visual medium, with vibrant posts that increase engagement levels.

Perhaps, this was the same reasoning behind Instagram activism: The visual medium would serve as a useful tool for activists to ‘market’ their causes.

According to a refinery29 article, Instagram is a platform where well-designed artwork, infographics and educational slideshows are widely spread, making a lot of social movements, complex political theories and issues accessible to the masses. In turn, this has facilitated robust discussions online, where the prettier and more readable the post, the more shareable it becomes. And clearly there is some truth in the rationale, just look at the popularity of US-based Impact and So You Want To Talk About, which combined have almost five million followers.

In Singapore, a growth in social justice accounts on Instagram appears to mirror this trend.

The various pages tackle issues that range from ethnic minority issues, to queer rights and intersectional climate justice. In order to understand more about the local activist scene on Instagram, TheHomeGround Asia reached out to six prominent Instagram activists. All of them juggle advocacy with schoolwork and/or day jobs, but have managed to create pages that are thriving, despite their overwhelming workload. They are:

- Sean Francis Han, a graduate student at the National University of Singapore;

- Sharvesh Leatchmanan, also a graduate student, majoring in gender, sexuality and women’s studies;

- Elijah Tay, a full-time student at Nanyang Technological University and works part-time;

- Kate Yeo, who awaits for university to start;

- Rachel Pang, who works in an administrative role;

- And Kristian-Marc Paul, who is a Diversity and Inclusion Lead in a global software corporation.

Why Instagram?

When asked, “Why Instagram?”, the local activists we interviewed gave similar answers.

“Using Instagram would make it easier to reach out to youths,” says Sean, the editor-in-chief of Wake Up Singapore. His sentiment was shared by Elijah, the founder of My Queer Story SG.

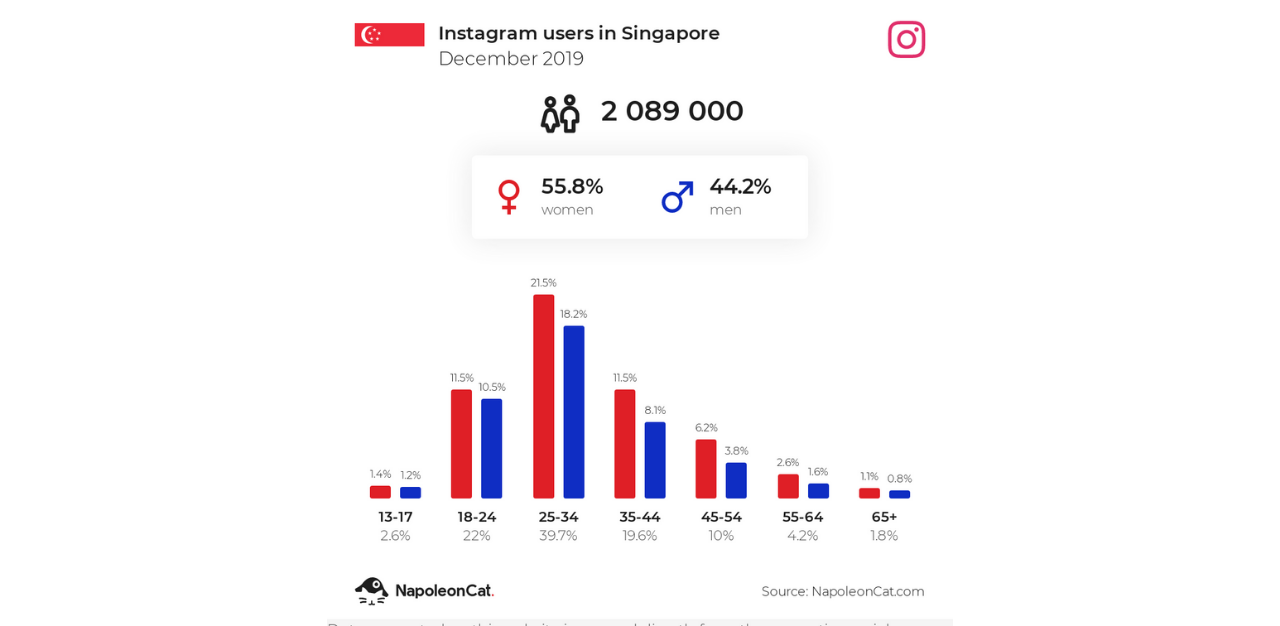

Looking at the survey done by Napoleon Cat in December 2019, 60.9 per cent of Instagram users are between the ages 13 and 34, which covers both Millennials and Generation Z.

It also makes sense to reach out to youths through activism conducted online.

A 2021 study conducted by the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy and the Institute of Policy Studies found that while Singaporeans are typically politically apathetic, younger Singaporeans are more politically active than their older counterparts.

Young Singaporeans between the ages of 21 and 35 are also more likely to have searched for political information online, donated to campaigns and causes and signed online petitions. This means that young Singaporeans are both familiar with online spaces, where they could get exposed to activism, and are politically active enough to feel compelled to take action.

Elijah explains, “Instagram is useful for sharing infographics because they can be easily shared on Stories. The 10-slide limit also helps to keep infographics succinct and easily digestible. It is also easy to collate information on Instagram, due to features such as Highlights.”

Instagram’s messaging and story features have also made it simple for activists to spur discussions amongst both their followers and non-followers. Functions such as poll stickers and question stickers allow for people to pose questions and offer answers.

Furthermore, Instagram is a place where “marginalised voices can take up space and be amplified in a way that mainstream media does not allow,” notes Rachel, founder of Rachel Pang Comics. Since marginalised voices rarely get a spotlight in mainstream media, Instagram is an ideal platform to magnify such voices, which is a form of activism in and of itself.

“The culture in Singapore around the need for a stamp of legitimacy means that people do not recognise that stories or anecdotes from individuals can be valid,” adds Kristian. “Opinions are valid and should have the space to exist. People think that what is socially acceptable as valid information only comes from academic sources.”

To that end, he states that Instagram has shone a spotlight on personal stories, in a way that mainstream media cannot.

Kristian, who is a member of the editorial team at SG Climate Rally, shares that while Instagram is not their main platform for activism, it has been useful for publicising their rallies and community outreach that are performed in physical spaces.

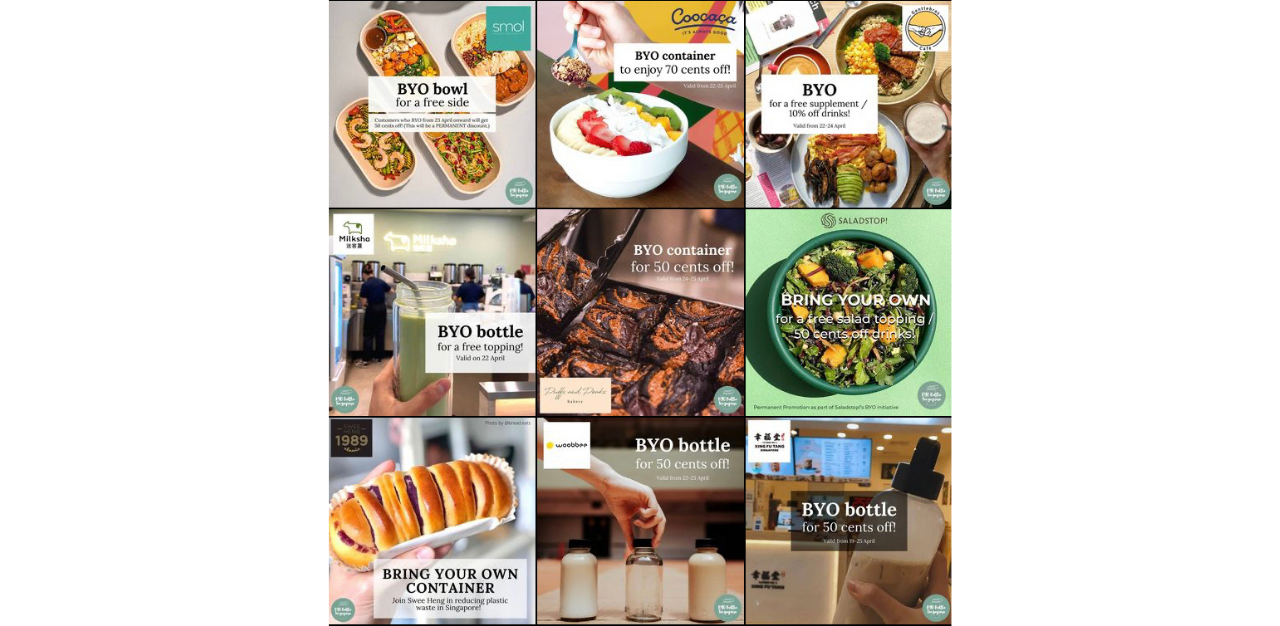

Kate, who runs BYO Bottle SG, states that Instagram is a great way for her on two counts. The first is to educate people about intersectional climate justice and sustainability. The second, to publicise on-the-ground efforts to encourage businesses and hawker stalls to adopt the BYO (Bring Your Own) campaign in their business model. This has built credibility and more food businesses have been willing to collaborate with her.

How and when did Instagram activism experience a boom?

The explosive growth in Instagram activism did not happen in a vacuum. Most of the events and trends that have precipitated the creation of activist pages were not controlled by these activists.

For Kate, it was the Straw-Free movement in 2018 that spurred her to take greater action in teaching people about the potential harm of single-use plastics.

In Rachel’s case, the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh as a justice on the Supreme Court in the United States, combined with their trauma as a sexual assault survivor, pushed them to start their page to share comics that illuminated sensitive and emotional issues.

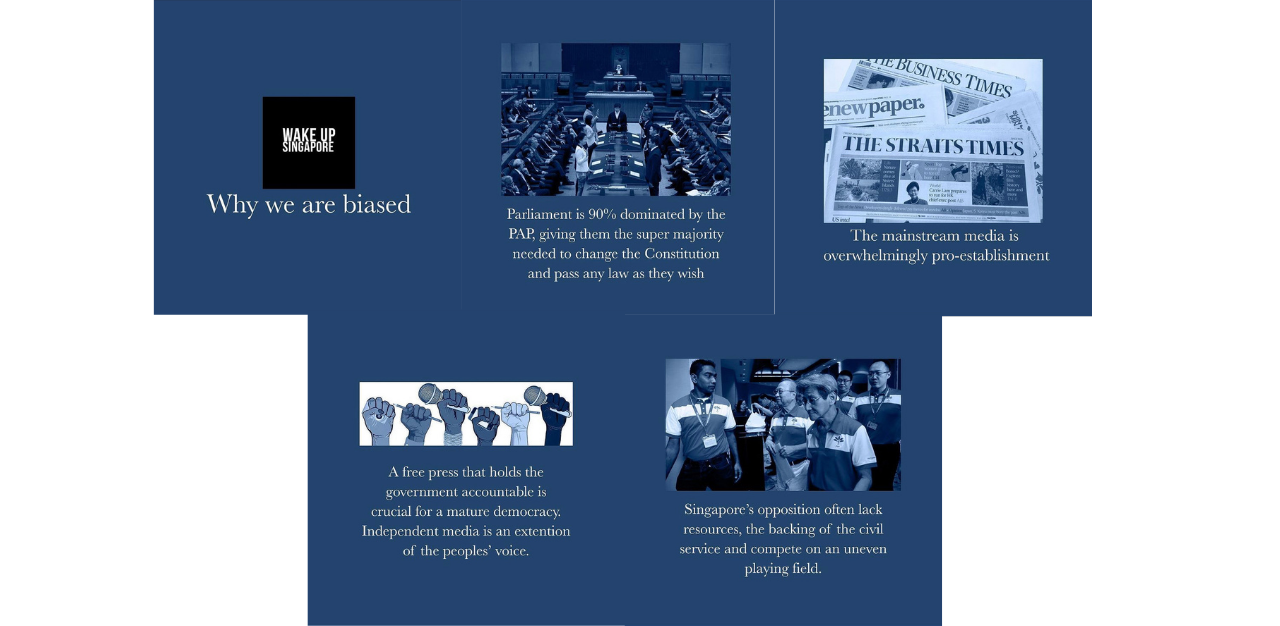

Wake Up Singapore found its calling out of the prevailing biases in mainstream media, and with the recent spate of racist incidents that led to the rise in visibility of Minority Voices, Wake Up Singapore ran the #CallItOut series airing personal experiences from people who had experienced racial discrimination, in Singapore.

Additionally, a dearth of stories and the spread of misconceptions about marginalised communities prompted Minority Voices and My Queer Story SG.

Novelty and a hunger for authentic, relatable, and community-led alternative sources of information appears to have also been instrumental to the massive upswing in the number of people following these pages.

National events, like the General Election, have also contributed to the popularity of pages like Wake Up Singapore and SG Climate Rally.

For BYO Bottle SG, a sudden spike in its number of followers came after a recent post detailing the unethical and unsustainable practices of SHEIN, a fast fashion brand.

While the recent spat of racist incidents led to the rise in visibility of Minority Voices and Wake Up Singapore, which ran a #CallItOut series.

What is telling is that the expansion in readership has mostly been organic. Many Instagram users have taken notice of these pages and gravitated towards its content.

Instagram activism isn’t just about mobilising people, it’s also about sharing stories

Activism is often thought to be more about on-the-ground action, spreading the word or promoting good causes, and drafting and signing petitions. But, sometimes it can be as simple as sharing stories, which pages like My Queer Story, Minority Voices and Rachel Pang Comics have primarily set out to do.

“My Queer Story started in 2018, during the height of the Ready for Repeal (R4R) movement,” says Elijah, “and also after [then Education] Minister Ong Ye Kung’s comments that LGBT people do not face discrimination in workplaces, or in schools in Singapore.”

They continue, “Someone mentioned during the R4R townhall that by encouraging queer people to share their stories of discrimination, it would help people realise the reality of the discrimination faced by queer people. Another person mentioned that for some queer people, it might be dangerous to reveal their identity when sharing such stories if they have not come out yet. So I thought, why not create a page that allows queer people to share their stories, while also giving them the option of anonymity so that they can share their stories safely?”

Sharvesh reveals that he had wanted to start Minority Voices in 2019, but did not have the courage to do so. He reached his tipping point, last year: “I had a lot of pent-up anger and frustration around the treatment of minorities, and it reached a peak when Lianhe Zaobao ran an opinion piece on the Covid-19 crisis amongst migrant workers,” he explains, “essentially saying that the reason why it affected migrant workers disproportionately was because of their cultural practices of eating with their hands, and not because of dormitory conditions.”

These perspectives “felt very discriminatory to me,” he says. “How could you blame an entire culture for a public health crisis?”

Rachel says, “Most of my comics are based on my life experience,” with some posts being inspired by their friends’ inputs, especially for topics that are extremely sensitive.

All three activists started their pages to normalise discussing minority and queer issues through a personalised lens, and to magnify narratives that are often under- or unrepresented in mainstream media.

How do you ensure factual accuracy?

Instagram is a gold mine for misinformation. And with fake news becoming more omnipresent and harder to spot, how do activists ensure accuracy in their posts?

In Singapore, those who spoke to TheHomeGround Asia recognise that they have a responsibility to practise due diligence and to fact-check thoroughly. The reasons being that many readers not only look up to them, but also rely on these pages for information and news, whether solely or to supplement other sources.

Sean says that most of their work involves sharing articles from mainstream media and offering different perspectives on those articles. Therefore, he thinks that there is close to no inaccuracy, since mainstream media outlets in Singapore are expected to have rigorous fact-checking processes. But, when Wake Up Singapore does share articles from less-established outlets, he notes that the team corresponds with other outlets to verify the accuracy of the story, before sharing it in their posts.

Kate and Kristian say that they gather multiple sources, sometimes up to 50 sources, especially academic journals, to instill rigour in the research process for their posts. For issues that they do not understand, the editorial team at SG Climate Rally reaches out to allies, specialists or academics to prevent inaccuracies in their content.

For personal testimonials, however, “believe victims” is the principle that pages like Minority Voices and My Queer Story SG uphold. Besides, the founders of both pages argue that they cannot challenge the accuracy of personal stories of discrimination, since they were not witness to what contributors have alleged happened.

What about bias?

All the activists who were interviewed state that they have been accused of being ‘biased’ or ‘unfair’. In response, they point out that the process of choosing a cause to advocate for is inherently biased.

Still, the practice of fairness offers a working solution to this conundrum, for some.

Kate, for instance, shares that she tries to shed light on alternative perspectives when people bring them up in the comments section, either by editing the caption to the relevant post, or pinning the comment with the alternative viewpoint.

But others say that they try “to own” their biases.

It makes “no sense” for Minority Voices, which was created to spotlight the often sidelined experiences of minorities, to cover the experiences of the Chinese majority, says Sharvesh.

And in the case of Wake Up Singapore, Sean says that its bias counteracts the bias in mainstream media, Hence, the team actively strives to promote perspectives that are left out, or do not receive as much attention in mainstream news platforms.

“There is a crucial difference between being biased and being critical,” says Kristian. “We believe that SG Climate Rally is critical.” He adds that SG Climate Rally is more interested in critically analysing the motivations of institutions, such as the State, corporations and mainstream media, in how they approach climate issues.

Therefore, even though SG Climate Rally might be biased in choosing to advocate for climate justice and making their personal views known, they believe that their bias is being used for good; educating people on climate justice issues and holding powerful institutions to account. An example is its Greenwatch initiative, which was created last year to analyse the climate policies of the political parties running in Singapore’s general election.

Still, there is an understanding that the optics around accusations of bias can detract from and derail its activism, says Kristian, “We try to use as many local academic sources as possible, so that we can avoid criticisms like ‘influenced by the West’.”

What are the downsides to Instagram activism?

Despite all the change for good that these activists try to achieve via social media, they are not immune to a fair share of hurdles and challenges.

Common side effects of running these pages are burnout and emotional exhaustion.

Many say that the research and editorial work that goes into creating content is often overwhelming, especially since they also juggle school work or day jobs. Furthermore, with a growing following, there is an increased pressure to keep posting.

To ameliorate this problem, Kristian says that the team at SG Climate Rally is trying to follow a content calendar, so that they can stagger their workload, and spread it evenly across the team, allowing them to post more consistently.

Kate says that she is also trying to set more boundaries and take more breaks, so that she will not exhaust herself. This is primarily because unlike SG Climate Rally, Kate is the only person running her account.

For people like Sharvesh and Elijah, since their pages deal with sensitive and emotional issues like minority and queer rights and discrimination, a lot of emotional labour is invested. Sometimes, the intensity puts them in a negative headspace or triggers them. Both are expanding their respective teams, as many hands make light work.

There is also the general culture of fear that activists have to deal with on a daily basis.

Sharvesh cites the anxiety of being reported to the police, and accused of “disrupting racial harmony” through his posts. Meanwhile, Sean states that the other team members behind Wake Up Singapore worry about their identities being leaked to the public.

On top of the culture of fear, activists have to face the regular barrage of critics and trolls.

“I receive comments like, ‘Oh, all the stories look like they have been written similarly, are you sure they are not fake?,’ says Sharvesh, “Which is ridiculous because who thinks that I have the time to invent stories about racism?”

He adds, “Of course there will be people in Singapore who believe that racism does not exist, so I cannot avoid those critical comments.” He tries not to take such comments personally, but when he does, it puts him in a negative space. For respite, he turns to friends for support or seeks professional help from a therapist, who guides him in processing these disruptive emotions.

Kristian says that SG Climate Rally does receive critical comments directed at them specifically, but acknowledges that they do not have to directly step in to address these comments, because the team has built an online community that engages with such critical comments, and converts those confrontations into constructive discussions.

Has Instagram activism worked?

Using data like engagement numbers is unlikely to suffice when quantifying whether Instagram activism has been effective. Besides, each activist has their own unique goals to achieve.

By and large, though, Instagram activism has been useful in raising awareness and educating people. As a loud hailer, Wake Up Singapore has been able to boost stories and perspectives that otherwise would not have had as wide a reach.

Sharing personal stories of discrimination through Minority Voices and My Queer Story SG has also helped increase the public’s understanding of what it means to be a minority, or queer in Singapore, further dispelling any myths or misconceptions.

The rates of learning and discussion have also risen because of Instagram activism.

While there are concerns about echo chambers, Instagram posts and stories are still accessible (via sharing, for instance) to those who might not be following these activists, or hold contrarian views. With such conversations taking place in the online space, everyone stands to widen their knowledge and understanding of complex and nuanced issues.

While Instagram activism is limited when it comes to achieving the ‘big’ goals, such as legislative and structural change, it has invariably made waves in Singapore’s society.

Many people in positions of power, including politicians and state officials, are starting to take notice of what these activists have to say.

Last year, the elections were dubbed the first ‘social media election’. Prominent Instagram activists and personalities, who were also from Generation Z, rallied to support opposition politicians, by educating their followers on opposition manifestos, and even held informal interviews with some opposition politicians.

Indeed, Instagram is proving to be a viable platform for activism.

As ground-up movements in Singapore become more adept at employing social media to champion their causes and the rights of marginalised communities, and their supporters’ voices grow louder and more emboldened, their ability to create change would be further assured.

With time, this ‘Instagramification’ of activism could lead to concrete systemic improvements for the greater good. As prominent American racial justice activist Gary Chambers Jr. says, “The revolution may not be televised. But they ain’t said nothing about social media.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.