There’s an overwhelming sense of pride when 36-year-old Ler Jie Wei talks about the running of his family business that is over a hundred years old.

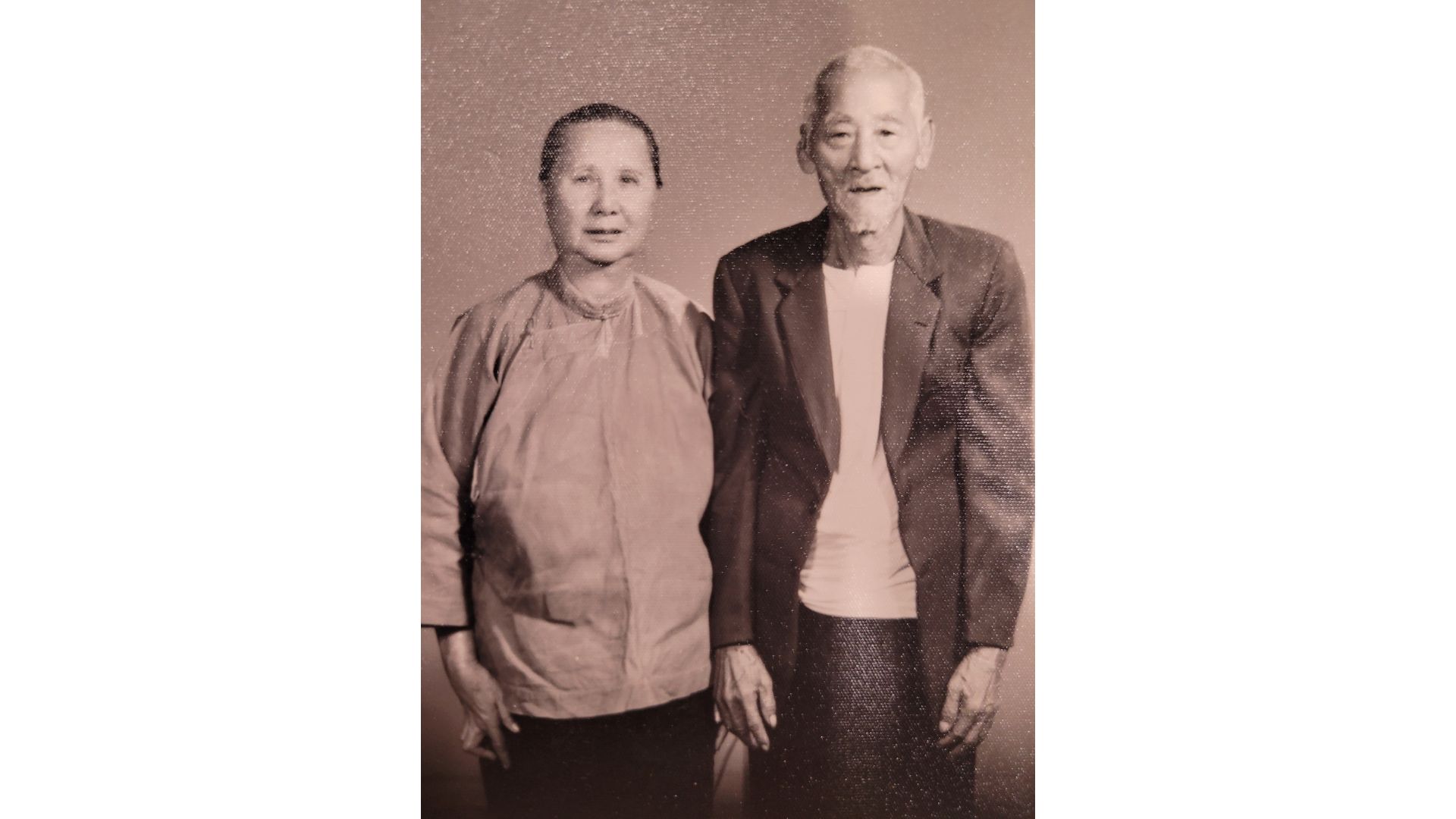

It was his great-great grandfather who started selling bowls of noodles with soup in the 1920s.

Chen Liang Fu, a Teochew immigrant from China’s Chao Zhou city, sold bowls of noodles with soup on foot around the Kampong Chai Chee area where he lived to eke out a living.

Back then, times were simple but hard and Chen, a street peddler, carried his makeshift portable kitchen on a bamboo pole. The literal burden on his shoulders strained his back to the point he developed a hunch, giving the noodles he sold the name “hunchback noodle”.

To Mr Ler, it is more than just a bowl of noodles with soup.

“When I was young, I used to see the regulars bringing their kids to the store and introducing this bowl of noodle to them. After taking over the business, I’m still serving those kids and even their kids. It’s not uncommon for three generations of a family to sit at the table and enjoy the noodles. It’s very satisfying to see this,” Mr Ler says.

He represents a younger generation of Singaporean hawkers, educated and sentimental, trading in corporate careers for the hawker trade, reversing a trend that left many ageing hawkers to fend for themselves, unable to pass down expertise to new blood.

“Most of my older patrons grew up in the old Kampong Chai Chee. They share with me that they relive their memories of the kampung days while eating my food. I find it very fulfilling to be a part of this legacy,” he adds.

Join TheHomeGround Asia as we slurp the noodles from Famous Eunos Bak Chor Mee and speak with Mr Ler on his struggles to continue his family legacy, and the importance of hawker culture in Singapore.

TheHomeGround Asia (THG): Why did you decide to take on the family business full time?

Ler Jie Wei (LJW): I graduated from NUS Business school before joining the banking industry. Generally, in Singapore, I feel that we are guided towards white collar office jobs. So, it’s always a gamble when we take over small family businesses and if they will be able to succeed.

Our bak chor mee is a soup-based family recipe passed down from my great-great grandfather. He carried the tools of his trade on bamboo poles over his shoulders and plied his ware around the Kampong Chai Chee area. The dish became known as “Hunchback noodles” from his posture resulting from carrying the poles. That is the image that I use as my logo for Famous Eunos Bak Chor Mee.

Even today, our soup-based bak chor mee is normally found only in the Eastern part of Singapore. Many distant relatives have since opened similar stores around Eunos and Bedok.

I’ve always felt a deep connection to this legacy left by my forefathers. This drove me to leave the banking industry and take up this challenge. It would’ve been a pity if the recipe were lost through the generations. After five years in banking, I made up my mind to leave and to learn the trade from my mum, who was running the business at the time.

THG: How did your friends and family react to your decision?

LJW: I don’t think anyone supported me initially. When I first told my mum, she wasn’t willing to teach me. She didn’t understand why I felt the need to quit my job after all the years of education only to endure the hard life of being in a hot kitchen and undergo the hardships of a hawker.

Parents of her generation tend to believe that office jobs provide a better quality of life. I had to force her hand by leaving my job. This was my way of trapping her to teach me everything she knows.

THG: What were some challenges you encountered?

LJW: My family business is no stranger to me because I’ve been part of it since I was young. I recall washing dishes in the back before moving on to the more technical stuff like wrapping the dumplings, and collecting the cash from patrons.

Despite that, I was still unfamiliar with the cooking process and other aspects of the business. That was when I quickly realised that I needed to learn all the “ins and outs” of our operation.

One funny challenge was having conflict with my mum. She had learnt the trade from my grandmother through verbal instructions and what is referred to as “feel”. You know, agak agak for this and that.

However, I am very scientific and detailed in my approach. She felt that it was very troublesome having to measure everything and this led to us clashing all the time.

I explained to her that I wanted to create a standard operating procedure (SOP) to regulate everything. It was necessary to be systematic and precise. I wanted to be able to pass a set of instructions down to a team, so that we could maintain the consistency of each bowl and grow the business further.

With a regular stream of patrons, it’s not merely about cooking one perfect bowl of noodles for one customer but being able to replicate that perfection with every bowl. Today, we record everything in precise measurements.

After a year of training under my mum, I opened an outlet in Lucky Plaza that I ran with my own team. I worked fifteen hours, every day, for the first three years there. The hours were challenging but eventually I just got through them.

It was necessary for me to go through that phase to learn everything possible to create the system I have today.

Thankfully, through the years, my mum finally agreed with my methods. She realised that what I was trying to accomplish was different from her.

I was trying to ensure that our recipe could be passed on to a next generation while she was more concerned with being the person who cooked each bowl of noodles.

THG: How did Covid-19 impact your business?

LJW: Initially we were very afraid as there was a lot of uncertainty during that time. Especially since it was our first time encountering such a lockdown. When the news came, my main concern was to my staff.

We were used to serving a single queue of customers at our stall front. So, when our orders transitioned to takeaways and delivery platforms, there was a sharp learning curve for us.

There was a lot of multitasking to handle the different orders from the different customers and platforms. Moreover, most hawker staff tend to be elderly, so it was challenging for them to be flexible and learn new skills quickly.

Even though our sales dropped, we were fortunate that we recovered better than expected, all thanks to our loyal customers. It’s not too bad. We are very thankful to have made it through.

At the point when our sales dropped, I channeled more time, energy and money into the backend of our business.

The government provided a lot of assistance in terms of rebates and grants. They provided monetary incentives for us to utilise point-of-sale systems, accounting software, and human resource management systems, all of which our business are currently benefiting from as we are more digitalised and efficient.

THG: Why do you find it important to preserve our food heritage?

LJW: I think that the hawker trade is truly unique to Singapore. It’s something that cannot be found elsewhere, and I believe that was recognised when hawker culture was inscribed in the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. I think that we should strive to preserve it for as long as possible.

However, I still feel that our society needs to give more recognition and appreciation to workers in the food and beverage (F&B). Even though we have awards and prizes, there is still the stigma that you work in F&B when you don’t have better options available to you. It’s a stigma that we should learn to get rid of.

In areas like Europe, there is a great pride to be in F&B. You are able to feel the pride a chef, barista, or restaurant manager has for the profession. I hope there is this push from the government and society to give more recognition to F&B workers.

We have seen in recent years that younger Singaporeans are joining the trade. I hope that this trend will continue as we need young and fresh blood to keep it going.

THG: Given the success of your recent rebranding efforts, how important is it to be versed in such skills to preserve our food heritage?

LJW: For my grandmother’s and mum’s generations, they work to put food on the table and tend not to have formal business structures and strategies.

There’s a Chinese saying -人在摊口在,人不在摊口就不在- which means that the operation of our stall used to be dependent on my mum’s presence.

This was when I realised the need to create an SOP so that the stall could run regardless of whether my mum or I are present. This philosophy has helped me expand the business.

We currently have three outlets and individual managers overlooking each one.

THG: What concerns do you have for the future of your business?

LJW: My main concerns are rising costs. Recent trade wars and uncertainty impact our bottom line. Labour costs also increased during the border lockdowns and the labour pool is getting smaller. These things keep me up at night.

Personally, we would like to keep our prices affordable for customers. I feel that our bak chor mee is a “commoner” dish, and we wouldn’t want to price it too high. It’s really a kampung food that we’ve been serving literally for a hundred years. I want to keep it this way for as long as possible.

THG: Anthony Bourdain once proposed a “hipster solution” to preserve Singaporean food, where traditionally the affordable price of food would increase to reflect the cost necessary for it to be economically viable. What do you make of this?

LJW: Our bak chor mee is not much different from a bowl of ramen. Although the ingredients and preparations are quite similar, there’s a stark difference between the market perception of ramen and bak chor mee.

I agree that as a society, we will have to come to a consensus on the prices we are willing to pay to make the hawker trade an economically viable one. If not, we run the risk of losing some of the family recipes.

If we can manage our perceptions, why not try something else? When we can increase our selling point, we can explore different opportunities. Maybe in a restaurant setting and focusing on a different audience.

But for now, we’re focused on serving the neighbourhood.

THG: Do you think your great-great grandfather would be proud of you?

LJW: I would like to think that he is. My mum for one is definitely proud of me. Despite the conflicts we had at the beginning, she’s now glad that our business has expanded, and the team has managed to keep it going. This keeps me motivated.

My aim is to increase the awareness of our bak chor mee both locally and internationally. Since it’s a part of my family legacy, I want as many people as possible to know about the dish.

THG: Do you have any message to aspiring hawkers?

LJW: I think the most important thing is to have passion in what you do. I may have grown up in a family of hawkers, but when I came to run the business, it was a totally different ballgame.

There are many hats to wear. Besides just cooking, you have to be the HR manager, accountant, sales manager, and much more. You may also need to be an electrician one day and a plumber another.

Passion really helps sustain you through hardship. It was what helped me endure my early days at the Lucky Plaza outlet.

Just focus on doing it and doing it right and I believe that one day the right opportunity will come for you.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.