The Well-being of the Singapore Elderly (WiSE) study published in 2015 by the Institute of Mental Health estimates that one in 10 people in Singapore above the age of 60 have dementia. In 2018, this constitutes almost 82,000 individuals. With Singapore’s ageing population, the Agency for Integrated Care predicts that this number will soar to 130,000, or more, by 2030. Given the rising number of individuals with dementia, how can Singapore transform itself into a more inclusive and hospitable country? TheHomeGround Asia speaks with caregivers and other stakeholders in the community to find out.

No doubt, Singapore has made strides in improving dementia-inclusivity within the community. Besides bolstering formal support for persons with dementia and their caretakers in the formal healthcare system, the Ministry of Health and Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) jointly launched the Dementia-Friendly Singapore (DFSG) initiative alongside other community partners. DFSG aims to encourage persons living with dementia to “continue living at home and go about their usual routines in their community.”

Various efforts have stemmed from this, such as Dementia-Friendly Communities, Dementia Go-To Points (GTPs), and dementia awareness campaigns. Most recently, GTPs were launched by transport operator SMRT in 17 of its train stations and five bus interchanges, adding to over 300 GTPs nationwide.

These GTPs are specified “safe return” points in the community, where persons with dementia who require assistance may go if they are lost, or if the public comes across an individual who needs help. These points are also staffed by individuals who have been trained on how to respond to and assist individuals with dementia.

While these efforts are laudable, stakeholders, including caregivers and service-providers, say that more needs to be done to create a dementia-friendly environment in Singapore.

A lack of awareness and action in the community

Belinda Seet, a caregiver to her mother, Katherine Lim, who was diagnosed in 2011 with Alzheimer’s disease, a type of dementia, and a volunteer with the Alzheimer’s Disease Association (ADA), relates that she witnesses many instances where individuals who may have dementia are left wandering helplessly in public.

For instance, during visits to the polyclinic with her mother, she often sees individuals who appear lost and are alone with no one to assist them: “A lot of times, [people] with dementia think they don’t need help, but they do. So they are left wandering in the polyclinic… they don’t know what to do; how to get themselves registered, how to go upstairs… and once they get to the floor, nobody helps them.”

Ms Seet thinks that service staff, retail staff, and even the police can be more understanding of those who may have dementia, instead of taking their actions at face value.

“Sometimes, a person with dementia forgets, and they take things without paying, then they’re caught, and they are charged with larceny and theft. But it’s not that they want to, it’s just that they forgot to pay,” she explains. “Sometimes, it’s not a matter of going by the law, they need to have some heart as well.”

She emphasises, “These people need to be educated.”

Her sentiments are echoed by Mary-Ann Khoo, a consultant at ADA, who is in charge of many of the organisation’s dementia-friendly initiatives and projects.

Ms Khoo believes that to create a dementia-friendly society, three fundamentals need to be in place: Raising awareness about the condition and addressing stigma; increasing touch points within the community; and involving individuals with dementia in efforts to improve inclusivity.

Having joined ADA in 2018, Ms Khoo brings her own experiences as a caregiver to her late father who had dementia. On first impression, she realised that while ADA had many initiatives like counselling and support groups, these are often for individuals who are already in ADA’s databases or are in formal settings, such as dementia day care centres or in nursing homes. Meanwhile, support for individuals in the community remains lacking, she says.

Raising awareness, stigma, and asking for help

When Marcus’ (not his real name) grandfather was diagnosed with dementia, he did not know what to make of it. Marcus recounts an instance during the circuit breaker period, last year, when his grandfather had gotten upset because the family had to ensure that he stayed at home.

“He went to the window and started shouting out to the neighbours, ‘Hey, help me, policemen help me,’” Marcus recalls. “We were shocked because this was the first time that he actually displayed this kind of aggression.”

During such moments, and others like it, Marcus and his family were at a loss as to how to respond. Eventually, the family called the Singapore Civil Defence Force for assistance, and they brought him for a check-up and found out that his state of agitation was caused by abnormalities in his potassium levels, rather than by dementia.

Throughout his grandfather’s struggle with his illness, Marcus was often unsure how to care for him and cater to his needs: “A lot of the time, when we were helping our granddad try to understand what was going on, it was a first-time basis for all of us… We weren’t prepared, more emotionally than physically or financially, but it can still be quite a shock,” he explains.

Marcus is not alone in his struggles. A study done by Singapore Management University and ADA of more than 5,600 individuals (including caregivers, individuals with dementia and the public) in Singapore discovered that more than half of the public rate themselves low in dementia knowledge, and almost 44 per cent report frustration on not knowing how to help them.

Among the caregivers interviewed, a lack of awareness about the illness was a common thread when their loved ones were first diagnosed. Ms Seet shares that she was terrified as her knowledge of dementia had been solely derived from the media.

“On TV and in the movies, you always hear of dementia, and then after a few episodes, you see that person dying… I was really scared because a few episodes means a few months [in reality],” she says. She has since been proven wrong; her mother, Mdm Lim, was diagnosed with dementia a decade ago and continues to do well.

Over the years, Ms Seet has learnt ways to maintain her mother’s cognitive function (doing assessment books, painting, cooking, and more), and has gained a broader understanding of what dementia entails through volunteering with ADA.

Similarly, Mr Tan was initially frustrated with his mother’s incessantly repetitive questions and remarks, and her paranoia, as he knew little about dementia. The lack of awareness does not just result in a steep learning curve for caregivers. Oftentimes, it can also encourage stigma towards those with dementia.

“Stigma can exist amongst people who have knowledge of dementia, and people with no knowledge of dementia,” Ms Khoo explains. “Even caregivers themselves have a stigma of the condition.”

In fact, the same study discovered that nearly 30 per cent of caregivers feel embarrassed in public while assisting their loved ones with dementia.

Ms Khoo elaborates that people may believe individuals with dementia tend to be violent and aggressive. But, she highlights that many of these behaviours are responsive in nature, and stem from a desire to share their discomfort, pain or anxiety.

“People with dementia may not be able to articulate that they are feeling pain, discomfort, or anxiety, so they can only express this through their behaviour,” she explains, acknowledging that they can be mistaken for being difficult.

“But they’re not. They’re just responding to something that they’re not comfortable with,” she shares. To tackle this, Ms Khoo highlights the importance of educating both the public and caregivers.

Danny Raven Tan, a caregiver to his mother living with dementia and founder of Enable Asia – a non-profit dedicated to enabling individuals with dementia to live a life of dignity – echoes the need to raise awareness.

“We must go out and shout, and educate people about what dementia is all about. By having the right education in place, I think a lot of problems will be solved,” says Mr Tan.

“If you see somebody acting funny on the street, don’t shun [them]. You investigate, if you want to help. Don’t just, ‘Oh, crazy.’ Don’t be so narrow-minded, just be nice.”

He adds, “Software, awareness, education, and if all these are in place, naturally, your community will be inclusive.”

Implementing touch points within the community

But with greater awareness comes a need for infrastructure to cater to those with dementia. And these spaces, says Ms Khoo, have to be within the community and not limited to specialised care facilities: “We can’t just keep building nursing homes and dementia day centres, and confining people within these spaces. We need to be able to make our community dementia-friendly.”

She likens the situation to that of mothers with young children, who may plan their day’s activities around places with readily available facilities, such as nursing rooms. Hence, she suggests creating more supportive services in the community for individuals with dementia, and running recreational activities, like dementia-friendly museum tours, movie screenings, or even reading clubs.

“The supermarkets, cinemas, food centres, libraries, museums, and everywhere; all of us with no cognitive impairment… we can do all these things anytime we want,” she rues. “But when [someone] gets dementia, they’re suddenly deprived of doing these normal things. Because the community doesn’t know how to interact with them, they are prevented from going out.”

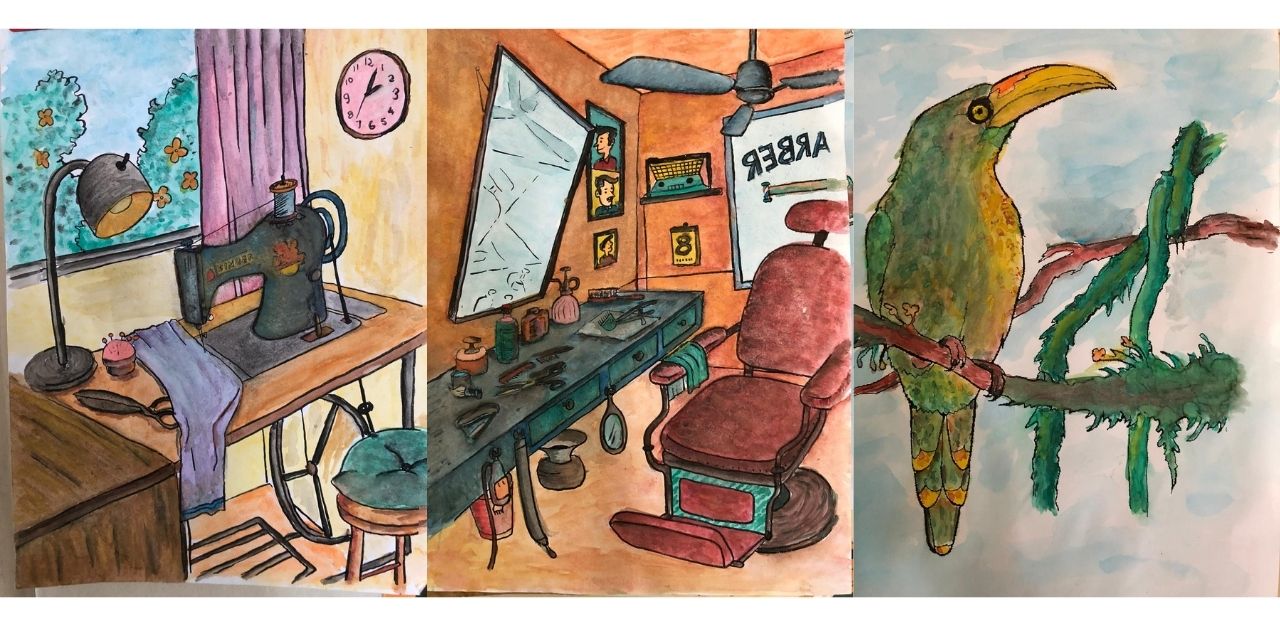

This is especially true for Michelle Ong, whose father, Thomas Ong, was diagnosed with dementia in 2019. Prior to that, Mr Ong was a school principal, and had been working until his diagnosis at age 79.

Ms Ong shares, “Suddenly, this man who has worked all his life doesn’t have a job. He just went into a state of depression, because it’s like [he has] no purpose in life anymore.”

To help her father work through his depression and keep his mind active, Ms Ong devised ways to engage him. Initially, she had purchased puzzle books for him, but the activity did not appeal to him.

“This man [father] is very, very smart,” she laughs. “He’s so smart that he said the puzzle games are not exciting, stimulating, or challenging enough.”

It is precisely this conundrum that Ms Ong hopes will be addressed: “There’s still much to be done to cater to people of my father’s calibre.

“There are many [people with dementia] out there who are probably graduates, professionals, and all that… That’s a group where maybe they can be engaged differently,” she suggests.

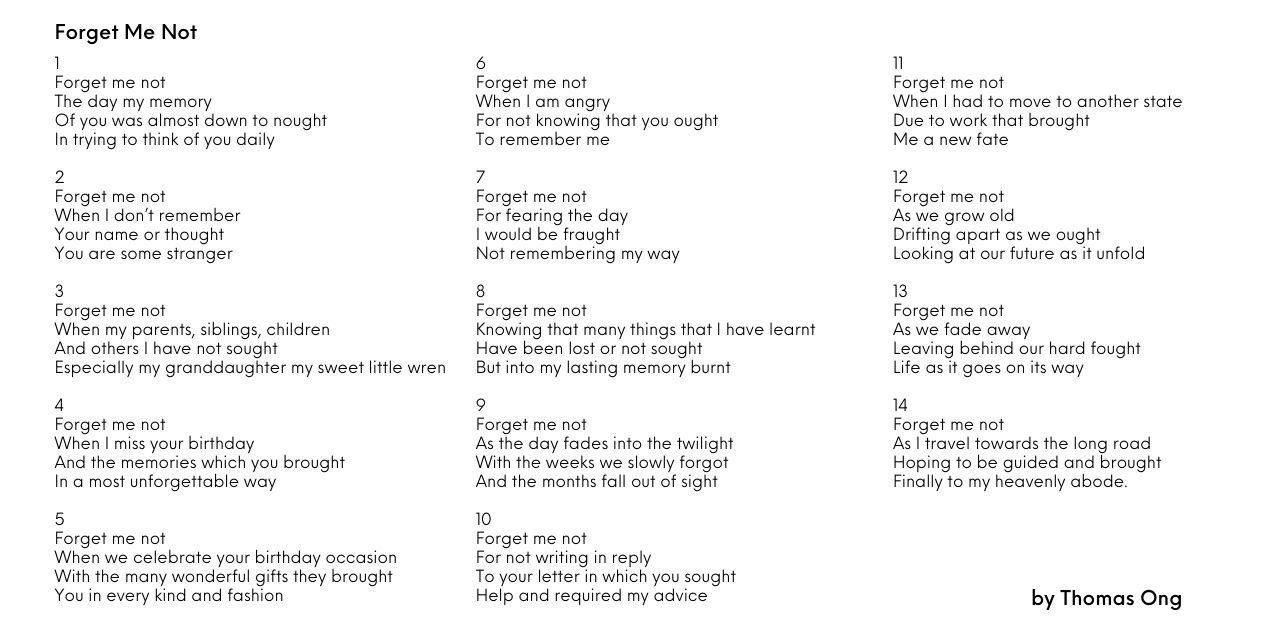

For now, Ms Ong is keeping her father engaged with activities such as painting and writing, and Mr Ong is writing a series of poems and prose for his memoir.

Involving individuals with dementia

The last point Ms Khoo raises is the need to involve individuals with dementia in conversations about inclusivity, and planning for a dementia-friendly Singapore.

“A lot of the time, the initiatives that are currently rolled out is by professionals, and these professionals are not living with dementia. It is one thing to talk about the symptoms… but it is a different thing altogether if you’re living with these symptoms 24/7,” she says.

The Wayfinding Project by ADA, for example, had engaged individuals living with dementia to share their ideas. The project consisted of a series of murals painted at HDB blocks, in order to help those living with dementia to recognise their surroundings and find their way home. It had taken into account the advice and insights given by two persons living with young-onset dementia.

Says Ms Khoo: “What was really helpful is them telling us that, ‘you giving me big numbers doesn’t help [me find my way]. Even if you put, for example, Block 160 under the block, it doesn’t help, because I cannot remember my block number. So you need to put icons that are simple and recognisable to me.’”

And so, murals that featured familiar and retro items such as tingkat containers were featured as part of the Wayfinding Project; they were easily recognised by the elderly and those living with dementia.

Welcoming people living with dementia into our communities

Dementia has a physical, psychological, social, and economic impact, not only on people with dementia, but also on their carers, families and society at large.

Caregivers told TheHomeGround Asia that they wished for the community to be more patient and kind when interacting with elderly individuals who might show signs of dementia. The hidden nature of the disability often makes it hard for an untrained eye to recognise the condition immediately.

Ms Khoo advises those who encounter someone in distress who might have dementia, to focus on both verbal and non-verbal cues when interacting with them. For example, she suggests that individuals approach from the front, make eye contact, and smile.

“Be relaxed and assuring… it’s your body language that assures the person with dementia as well,” she says.

Furthermore, she advises good Samaritans to take the time to speak slowly and clearly, using simple words and short sentences to get their point across. Ms Khoo adds that when asking questions, it should be done one question at a time to avoid confusing these individuals.

“What is important is to be patient, give them time to think and respond,” she emphasises.

To learn more about dementia and how to approach individuals with dementia, AIC has developed an e-learning module that educates the public about the illness.

Ultimately, Mr Tan reminds caregivers and the public that people living with dementia “are not trying to be difficult.”

“They are not trying to give you a hard time,” he adds. “They themselves are having a hard time.”

Mr Ong reads a poem he wrote as an individual living with dementia, explaining: “It’s called Forget Me Not. Reason being, a person with dementia is quite often forgotten. So the message to the world is forget us not.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.