Around the world, long-ruling parties have been falling after decades in power. Voters rattled by economic woes and political fatigue are toppling incumbents in even the most established democracies. In Britain, the Conservative Party’s 14-year reign ended in a landslide to Labour in 2024. In the United States, the ruling incumbent party has lost the White House in three consecutive elections. India’s once-dominant Congress Party, which governed for much of the country’s first 30 years, was decisively unseated decades ago by rivals. More dramatically, some of the world’s longest-ruling parties have finally been cast out: Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary Party lost its 71-year monopoly in 2000, and Malaysia’s Barisan Nasional shockingly fell in 2018, ending a 60-year grip on power. Even in South Africa, the African National Congress dipped below a majority for the first time in 2024.

Such global precedents loom large as Singapore approaches its own momentous vote on May 3, 2025. The long-ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) has dominated Singapore’s politics since 1959 – over 66 years of uninterrupted rule. Singaporeans are keenly aware that in other nations, no party’s reign lasts forever. As one observer noted, 2024 was “a tough year for incumbents” worldwide. This international wave of political turnover begs the question: Could Singapore’s seemingly invincible ruling party finally lose its shine?

The Singapore Exception – One-Party Dominance

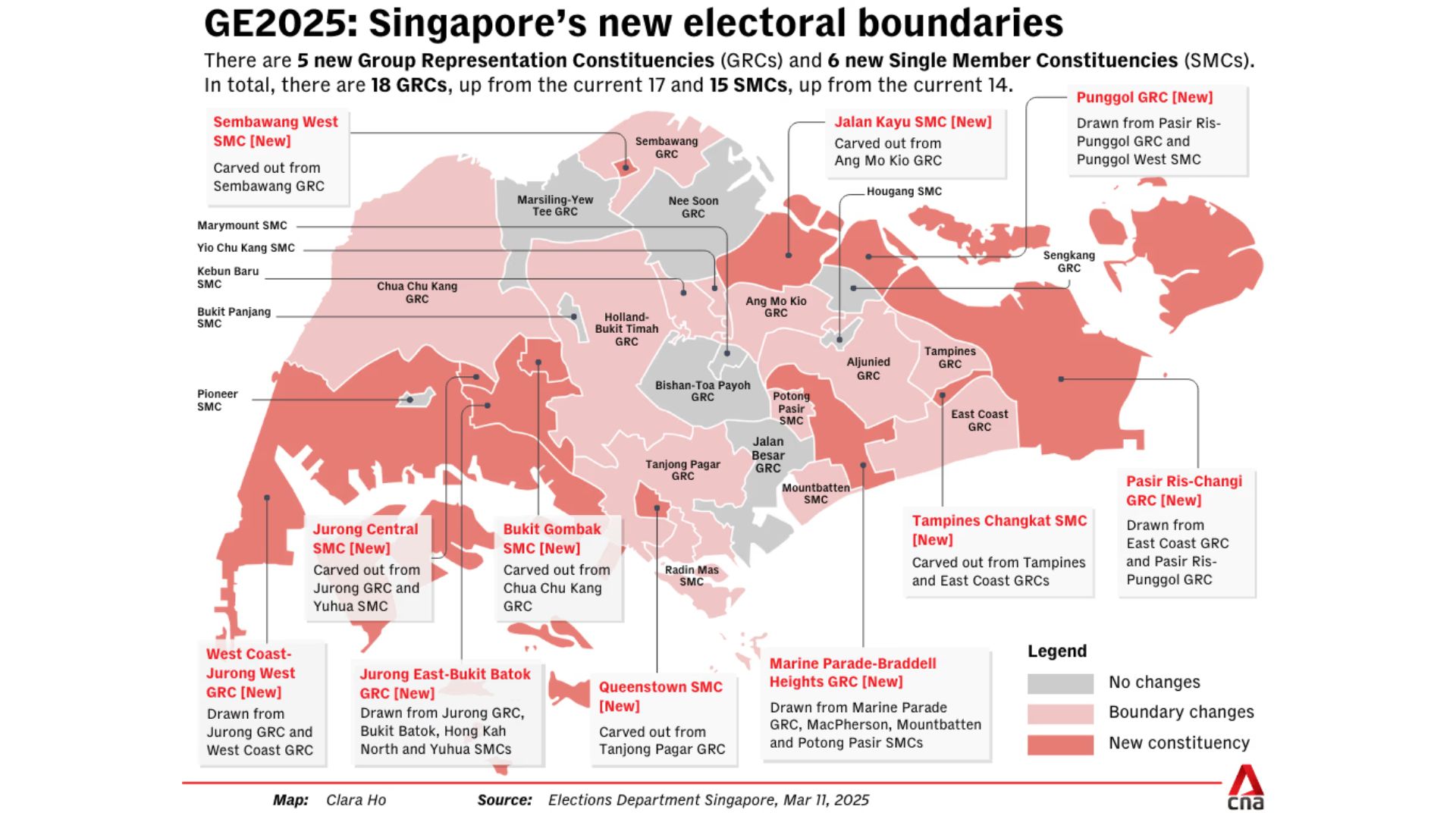

Singapore’s political landscape has long been unique. The PAP has won every election since self-governance in 1959, usually by wide margins, and has held a supermajority of seats in Parliament for the country’s entire post-independence history. This dominance is buttressed by a first-past-the-post electoral system, including multi-member Group Representation Constituencies (GRCS), which tends to magnify the PAP’s seat count even when its popular vote dips. For example, in the last general election of 2020, the PAP won 83 out of 93 seats with just 61% of votes. The opposition’s votes were too scattered to translate into many seats. The Workers’ Party (WP), the main opposition, made historic inroads that year by securing 10 seats, the most ever won by the opposition. Still, that was barely 11% of seats, underscoring how extraordinary PAP’s dominance has been.

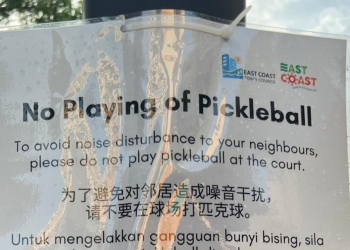

Several features set Singapore apart. Elections are regularly contested (only a few walkovers nowadays), yet the playing field is tilted. Constituency boundaries are redrawn before elections in ways the opposition alleges disadvantage them, and short campaign periods and strict rules curb outreach. The mainstream media – largely controlled by government-linked companies, gives heavy coverage to the PAP, while opposition voices struggle for equal airtime. Freedom of speech is circumscribed by defamation laws and anti-“fake news” regulations (like the 2019 POFMA law) that, critics argue, can be used to muzzle dissent. Unsurprisingly, Singapore ranks just 129th out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index.

Yet, unlike many long-ruling parties elsewhere, the PAP has maintained a reputation for technocratic competence and clean governance. It has presided over stability and exceptional economic growth, transforming a poor port city into a wealthy global hub. Public trust in the PAP-led government remains high by international standards, built on low corruption, efficient public services, and a narrative of delivering prosperity. Many Singaporeans credit the PAP for the nation’s success and value the stability of one-party rule. This has long inoculated the PAP against the anti-incumbency swings seen elsewhere. As a recent survey found, 58% of Singaporeans feel the country is moving in the right direction (only 14% say it’s on the wrong track), often citing stability, safety and good leadership as reasons.. These are the PAP’s stock-in-trade.

Winds of Change Since 2020

Even so, the 2020 election signalled the gradual opening up of Singapore’s politics. The PAP’s 61.2% vote share in 2020 was one of its worst performances ever, and the opposition WP achieved its best result, winning 10 seats, including its second GRC. The PAP still retained an overwhelming majority, but the message from voters was clear: there is appetite for more opposition voices in Parliament. Since then, Singapore has seen further political shifts. Longtime Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, son of founding PM Lee Kuan Yew, has handed over leadership of the PAP to a new generation. In May 2024, Mr. Lee stepped aside, and Lawrence Wong became PAP Secretary-General and Singapore’s Prime Minister. This election will be the first led by someone not from the Lee family (or their close circle) in over 30 years. Mr. Wong, 52, faces the task of maintaining his party’s dominance without the aura of his predecessors. He has already acknowledged the battle ahead, warning at the campaign’s outset that “there are no longer any safe seats” for the PAP and that “every seat can be hotly contested”.

The Workers’ Party has solidified its role as the leading alternative voice on the opposition side. WP’s chief, Pritam Singh, was designated Singapore’s official Leader of the Opposition after 2020, a symbolic move recognising the opposition’s growing presence. The WP will aim to defend its constituencies (notably Aljunied GRC, Hougang SMC, and Sengkang GRC, which it seized in 2020) and possibly expand further. Meanwhile, other opposition groups are trying to make their mark. The Progress Singapore Party (PSP), led by former PAP stalwart Dr. Tan Cheng Bock and newcomer Leong Mun Wai, nearly won a GRC in 2020 (West Coast) and secured two seats as Non-Constituency MPs. The PSP and WP have thus far avoided clashing with each other, focusing on different regions. Smaller parties like the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP), National Solidarity Party, and new entrants have formed an alliance or plan to contest more seats. The opposition landscape is more crowded than ever, a double-edged sword for the anti-PAP cause. While it signals rising enthusiasm to challenge the status quo, it also raises the risk of multi-cornered fights (three- or four-way races) that split the opposition vote. Analysts note that whenever multiple opposition candidates run in one ward, the ruling party tends to benefit from the divided vote. Despite attempts at “horse-trading” agreements to allocate seats, coordination among the many opposition parties has become harder. This fragmentation could ironically shore up the PAP’s position even if the opposition vote grows.

Another change since 2020 is the forthcoming leadership transition within the PAP. Prime Minister Wong represents the 4th generation of PAP leadership. The PAP has also rejuvenated its ranks, introducing over 30 new candidates this election – its largest slate of fresh faces in years. This renewal signals that the party is not resting on its laurels. Mr. Wong even delivered what was described as a “full-blown election budget” earlier this year, packed with subsidies and benefits for voters. Clearly, the PAP is using its incumbency advantage to address pain points and court the electorate ahead of polling day.

Bread-and-Butter Pressures

If anything has the potential to loosen the PAP’s stranglehold, it is voter discontent over bread-and-butter issues. Singapore’s economy has hit headwinds recently – growth has slowed (forecast at roughly 0–2% for 2025), hit by global trade woes and pandemic aftershocks. More palpably, Singaporeans are feeling a squeeze in the cost of living. After decades of low inflation, the past two years brought a sharp uptick in prices. Global inflation, supply chain disruptions, and a hike in Singapore’s GST (goods and services tax) from 7% to 9% have all contributed to higher prices for everyday goods. It is no surprise that the cost of living has emerged as the number one concern for voters. In a January 2025 survey of Singaporeans, 35% picked “cost of living and inflation” as a top issue influencing their vote – by far the most cited issue, well ahead of jobs (16%) or economic growth. Another poll found that a whopping 72% of Singaporeans overall consider the cost of living the nation’s most pressing problem. This anxiety cuts across political leanings, but it’s especially pronounced among those inclined to vote opposition. Opposition parties have seized on rising living costs, from electricity bills to food prices, as evidence that fresh ideas are needed to tackle affordability.

Housing is the other hot-button economic issue. In land-scarce Singapore, over 80% of citizens live in public HDB flats, and housing affordability is always a political topic. In recent years, resale flat prices have skyrocketed, fuelled by limited supply and pandemic-related construction delays. HDB resale prices jumped by roughly 10% or more annually in 2021 and 2022, amounting to a ~28% surge over two years. That has put young, first-time homebuyers in a bind, as they face long waits for new flats or very high resale prices. The government has rolled out measures to cool the housing market (and 2023 saw price growth slow to about 4.8%), but affordability remains a key voter concern – especially among younger Singaporeans. In surveys, housing costs rank among the top three issues for voters under 50. The PAP has acknowledged the problem and accelerated building new flats, but the opposition will likely argue it could have done so sooner.

Meanwhile, Singapore’s famously low unemployment crept up during COVID-19 (though it remains low by global standards, under 3%). Job competition is intertwined with another sensitive issue: immigration. Singapore relies heavily on foreign workers, from construction labourers to white-collar professionals. As the economy rebounded post-Covid, the non-resident population (mostly foreign workers and expats) swelled by 5% in one year, reaching 1.86 million – nearly one-third of the total population. The total population hit a record 6.04 million in 2024. While foreign labour fills crucial gaps, many locals worry about strains on infrastructure, housing demand, and job competition for Singaporeans. Opposition figures have often tapped into these sentiments, calling for tighter controls on foreign manpower and more opportunities for locals. The PAP counters that an open talent pool is vital for economic growth and has policies to ensure that Singaporeans are prioritised. Still, the nuances can get lost in emotive debate.

Underlying these economic issues is a broader concern about inequality. Singapore is a wealthy society but also one of the most unequal among developed nations, with a high Gini coefficient (though government transfers reduce it). The sight of gleaming condos and luxury cars contrasts with the struggles of lower-income retirees and young families coping with high costs. The PAP government has taken steps – such as introducing a minimum wage-like policy (Progressive Wage Model) for some low-wage jobs and expanding social aid – yet some feel it is still insufficient. The opposition parties, especially the SDP, often campaign to address the income gap and enhance social safety nets.

Youth and the Evolving Electorate

Singapore’s electorate is changing demographically and in terms of attitudes. Over 40% of voters are now below age 50, a cohort that does not personally remember the turbulence of the 1960s or the poverty of the early years. Younger Singaporeans have known only life under PAP rule, but they are also more exposed to alternative views via social media and the internet. Millennial and Gen Z voters tend to be less automatically loyal to the PAP than their elders. Surveys show that only about 50% of millennials think the country is on the right track (versus 66% of boomers), and younger adults express more uncertainty about Singapore’s future direction. Crucially, younger voters are also the most undecided when it comes to political choice – about one-third of voters in their 20s haven’t committed to any party yet. This makes them a key swing segment. Many prioritise issues like housing affordability, climate change, and greater freedom of expression. They are also active consumers of online news and tend to distrust state media.

Social media has somewhat levelled the playing field for the opposition. Platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Telegram are awash with political discourse during elections, and independent media outlets and citizen journalists have carved out an audience. The Workers’ Party and others have upped their social media game to engage young voters (who might never read the state newspaper). This digital sphere offers the opposition a way to bypass traditional gatekeepers and get their message out, though the PAP, too, has a significant online presence and the advantage of the controversial POFMA law that can require tech platforms to append “corrections” to posts the government deems false. Still, the online battleground reflects a genuine hunger for debate among many Singaporeans, especially the youth. Issues like LGBTQ rights, environmental policy, and freedom of speech – once muted topics are now openly discussed, even if not yet central in election manifestos.

Youthful idealism, however, meets a pragmatic streak in Singapore’s electorate. Even many younger voters who desire a stronger opposition say they want gradual change, not chaos. The memory of regional upheavals, for instance, Thailand’s protests or Hong Kong’s turmoil, makes some cautious. The PAP’s messaging often plays on these stability concerns, urging voters not to “experiment” recklessly. In past elections, fear of instability has driven a late “flight to safety” swing back to the PAP. In 2015, after a weaker PAP showing in 2011, Singaporeans delivered a strong mandate to the PAP (nearly 70% vote) amid SG50 patriotism and regional uncertainty. The PAP may hope for a similar effect in 2025: that voters, faced with economic uncertainty and global tensions, will stick with the tried-and-true party. As one analysis noted, in earlier eras, many Singaporeans ultimately valued continuity, but today, the landscape is more polarised between those prioritising stability and those eager for change.

Trust, Governance and Freedom

A core pillar of PAP’s legitimacy is its record of good governance. Singapore consistently ranks at the top for lack of corruption. The government is famously efficient and forward-planning. These strengths remain, but recent events have tested the PAP’s squeaky-clean image. In 2023, a senior PAP minister was embroiled in a rare corruption probe – Transport Minister S. Iswaran was subsequently charged and convicted of obtaining gratification as a public servant and one charge of obstructing justice. It’s the highest-level corruption case in Singapore in decades. The PAP swiftly removed him from duty, and Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong (at the time) stressed that no one is above the law. Still, the episode was a jolt to Singaporeans who took pride in having virtually zero government corruption. Analysts said the ruling party would “almost certainly have to pay a political price” for such a blemish, depending on how it restores public trust. Likewise, a spate of other controversies – the resignation of the Speaker of Parliament over an affair, questions over the rental of state-owned mansions by ministers – have given the opposition fodder to question the PAP’s moral authority. These incidents are minor compared to the scandals that have felled regimes elsewhere (nothing on the scale of Malaysia’s 1MDB fraud, for instance). Still, they chip away at the PAP’s narrative of exceptionalism.

Another facet is the degree of political openness. Singapore’s electorate is educated and increasingly cosmopolitan. Many, especially the young and middle-class, desire more transparency and democratic freedoms corresponding to Singapore’s developed nation status. International indices classify Singapore as only “partly free” politically, citing media self-censorship and constraints on civil liberties. The government argues that its model, limited public dissent but competent rule, has delivered results and that Western-style liberal politics might sow division in a multi-ethnic society. Indeed, many Singaporeans accept some curbs on free speech in exchange for harmony and growth. But there are signs this social compact is shifting. Civil society and advocacy groups (on issues from migrant worker rights to environmentalism) have become more vocal. While large street protests are virtually unknown (save a controlled Speakers’ Corner), public sentiment for greater openness has grown. For example, critics raised concerns about overreach when the government passed a law against foreign interference online. And on the free press front, Singapore’s media rankings – hovering in the bottom third globally – are a point of embarrassment for some citizens who want a more open flow of information.

How these soft issues of governance and freedom translate into votes is uncertain. The PAP’s superior track record in delivering housing, healthcare, education and jobs often matters more to the average voter than abstract freedoms. However, even loyal voters might be swayed if the PAP is perceived as arrogant or out of touch after decades in power. The 2020 election post-mortem, for instance, suggested that younger, well-educated voters resented what they saw as the PAP’s dismissive attitude toward opposition proposals and the heavy-handed use of laws like POFMA during the campaign. Maintaining public trust in the government’s integrity and fairness is crucial for the PAP. The PAP has reminded voters that it should not be taken for granted. Prime Minister Wong has said he “does not assume the PAP will automatically win” and that the party must “fight for every vote”. This uncharacteristic humility is likely aimed at countering any voter urge to “teach the PAP a lesson” if it appeared too complacent or high-handed.

Scenarios: Change or Status Quo?

As Singapore heads to the polls on May 3, several scenarios are possible, each with profound implications:

-

1. PAP Narrow Victory with Weakened Mandate: The most discussed scenario is that the PAP wins again but with a reduced majority. This could entail the opposition gaining more seats – perhaps WP capturing another GRC like East Coast or PSP winning West Coast GRC – pushing total opposition MPs to a new high (maybe 15-20 seats). PAP could even lose, for the first time, the two-thirds supermajority needed for constitutional changes. The PAP’s popular vote might fall further, say to the mid-50s %. Such a result would be a political earthquake by Singapore standards (even though PAP would still govern). It would signify a clear desire among voters for a stronger opposition voice and more accountability. The PAP would remain in power but under pressure to reform its style of governance and address the issues that drove voters towards alternatives. Many observers view this as a plausible outcome if younger and swing voters indeed act on their frustrations over the costs of living and if no late pro-PAP swing occurs. Notably, more than one-quarter of voters are still undecided on the eve of the election, their choices will be decisive. And about 22% of Singaporeans already say the PAP has been in power “too long” and that change is necessary, a sentiment unheard of a generation ago. This scenario would be a political watershed for Singapore: The PAP’s dominance would be reduced but not eliminated.

-

2. Continued Dominance – Status Quo or Even a Rebound: It is very possible that the PAP will retain roughly the status quo or even improve its showing due to incumbency advantages and voter caution. The PAP could still capture the bulk of the 97 seats, with the opposition gains limited to maybe one or two constituencies. In a favourable case for PAP, it might even wrest back a seat or two (for instance, regaining Sengkang GRC from WP). The ruling party has formidable strengths: a deeply entrenched ground network, the ability to roll out popular policies (grants, public housing upgrades, etc.) just in time, and a pulpit to frame the narrative. In this rosy scenario for PAP, voters might decide that amid economic uncertainty, it is safer to stick with experienced hands. PAP’s new leader Lawrence Wong would claim a strong mandate, cementing the leadership transition. Such an outcome would echo 2015, when the electorate swung back to give the PAP a resounding victory after an earlier scare. It would suggest that while Singaporeans may grumble about issues, a majority still trust the PAP to handle those problems better than an untested opposition. A “flight to safety” impulse – prioritising stability and familiarity – has benefited the PAP before and could do so again. Under this scenario, the PAP’s continuous rule marches on essentially unbroken, albeit with the knowledge that it must not grow complacent.

-

3. The Unthinkable Upset – PAP Loses Power: A true upset – the PAP losing its parliamentary majority remains a remote wild card scenario, but it is no longer completely unthinkable. For this to happen, virtually everything would have to go right for the opposition: a large nationwide swing against the PAP (perhaps its vote share plunging well below 50%), the opposition winning many straight fights in key GRCs, and avoiding splitting votes in marginal seats. One could imagine a perfect storm, maybe a significant scandal or economic crisis inflames public anger, and opposition parties coordinate enough to present a united front, leading to the PAP being swept out. It would require the opposition to capture at least 47 seats to form a majority coalition. Given that they currently hold 10 elected seats, this would mean winning dozens of new seats, a monumental leap. The likelihood of this happening in 2025 is exceedingly low by any measure. The opposition simply lacks the nationwide machinery and senior leadership figures to run the government. Indeed, the WP’s approach has been cautious, positioning itself as a constructive check rather than explicitly calling to govern. However, the mere notion of a possible alternation in power is now discussed, whereas it was beyond imagination for decades. If such an upset did occur, Singapore would be placed in uncharted waters. A coalition of WP, PSP, and others might have to assemble a government quickly, which is likely a shaky proposition. The PAP, relegated to opposition, would still command a large minority of seats and could be expected to fight tooth and nail. International investors might panic initially, given Singapore’s reputation for political stability. In short, while this scenario is highly unlikely in this election, the fact that it merits contemplation is itself a sign of changing times. It took 60+ years for dominant parties in Mexico or Malaysia to finally fall. Has Singapore’s PAP reached its threshold? Whether 2025 is the moment or not, one-party dominance is not immutable in a democracy.

Data Points: Voter Sentiments in 2025 (Survey Highlights)

| Indicator | Result |

|---|---|

| Country moving in right direction (Yes) | 58% (14% say wrong direction) |

| Undecided or swing voters ahead of an election | ~27% (incl. 33% of ages 21–29) |

| Believe PAP has been in power for too long | 22% (want a change in government) |

| Top voter concern: Cost of living/inflation | 72% cite as a significant issue |

| Other major concerns: Healthcare for ageing | 41% |

| Housing affordability | 36% |

| Trust in the current government’s accountability | Generally high |

(Sources: YouGov March 2025 poll, Blackbox Jan 2025 survey)

An Election like No Other

As Singaporeans head to the ballot box, they do so in the context of global and local cross-currents. Globally, voters are ousting long-time incumbents from London to Kuala Lumpur. Locally, the PAP’s aura of invincibility has dimmed somewhat, the opposition is at its strongest point in history, and public grievances on everyday issues are palpable. Still, the PAP’s record and machinery are formidable, and many Singaporeans genuinely fear risking the stability that has underpinned their prosperity. The upcoming General Election 2025 is thus a genuine contest of ideas and trust, even if the PAP remains the odds-on favourite to win the most seats.

Singapore’s founder Lee Kuan Yew once said that a credible opposition was necessary “so that if the PAP fails, Singapore can be taken over” – though he added that it would take “decades” to build. Those decades may be reaching a culmination. This election will show whether Singapore’s electorate is ready to inch toward an era of greater political pluralism or prefers to keep faith in the party that got them here. Even if the PAP retains power, the era of monolithic dominance may be drawing to a close. A strong opposition showing would herald a new chapter in Singaporean politics, forcing the PAP to adapt and rejuvenate further. Conversely, a resounding PAP victory would indicate that Singapore’s blend of “democracy-lite” paternalism still resonates with the majority, albeit with an expectation that the PAP diligently addresses voters’ real concerns.

One might say that the pragmatic Singaporean voter will weigh the desire for change against the comfort of continuity. The PAP’s streak of more than 60 years in power is on trial, but it is not yet at an end–unless an extraordinary wave of sentiment sweeps the island. The 2025 campaign has been the most spirited and data-driven in Singapore’s history, replete with opinion surveys, social media debates, and open acknowledgement of issues once tiptoed around. Come May 3rd, the results – data in hand – will answer a question for the ages: Can the ruling party of Singapore finally be voted out after generations in office? The PAP isn’t taking any chances, refreshing its slate and urging voters to focus on proven governance. For its part, the opposition asks Singaporeans to imagine an alternative after 66 years.

RELATED: Opinion | The Risk of Sameness: Why Diverse Voices Matter in Singapore’s Politics

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.